In this episode, we sit down with Mountain Hardwear athlete and Olympian Kyra Condie. Kyra has so much psyche and energy, and we had a wide ranging conversation, covering her past, present, and future climbing exploits. We start off with her experience winning the Hueco Rock Rodeo in 2017, her advice for competitors this year, and how her spinal fusion pushes her to have a creative mind and find her own beta. She also gave some excellent insight into the way comp climbers think, the key training focuses every climber should have, and how MORE climbers should get on routes and problems that are way too hard for them. Kyra is really open about dealing with fear of falling and fear of the unknown, and we unpack that and more, diving into relatable topics for most climbers. Finally, we cover her Olympic hopes for Paris 2024. Whether it's strategies for competing in Hueco, training tips, or mantras for good mental game, Kyra’s wisdom is worth the listen!

Fix CRUS: Help Protect Public Access to Recreation in Colorado!

Photo by Katie Sauter.

Policy Alert: Take Action!

As climbers, many of us are familiar with the often delicate and fragile access to climbing on private land. In Colorado, we now have the opportunity to pass legislation to ensure that our access to our beloved climbing areas is no longer so tenuous.

The crux of the matter is liability. The current Colorado Recreational Use Statute (CRUS) has private landowners concerned about the liability they take on when they allow the public to access their lands for recreation. The result has been a drastic number of closures or uncertainty for some of Colorado's most iconic recreational areas—including 14ers, attending the Leadville 100, and even climbing in Ouray Ice Park.

The AAC is part of the Fix CRUS Coalition, and we have worked alongside our partners as they crafted SB-58, a landmark bill that will fix the Colorado Recreational Use Statute (CRUS), ensure the balance of landowner rights, and protect public access to our state's natural wonders that are on private land.

Now, we need your voice to turn this work into a reality. This impacts more than just Colorado climbers, but our entire outdoor family that utilizes Colorado lands.

What SB-58 Does

This bill takes a carefully balanced approach to help limit landowner liability exposure while ensuring visitors are aware of non-obvious or man-made hidden hazards. SB-58 would do the following:

Protect landowners who put a warning sign up with pre-approved language at the main access point from lawsuits related to most natural, agricultural, and mining-related hazards.

Clarify that visitors must use a designated access point, stay on trails and within approved areas or they will be classified a trespasser for purposes of liability (not criminality).

Update which recreational activities are protected by CRUS, to include rock climbing, ice climbing, trail running, backcountry skiing, rafting, and kayaking, etc.

Your Role: Advocate for Colorado's Outdoors

Your voice is crucial. We urge you to contact your Colorado State Senator and Representative and express your support for SB-58 asking them to support and cosponsor the bill.

SB 58 is a bipartisan bill sponsored by Senators Mark Baisley and Dylan Roberts, and Representatives Shannon Bird and Brianna Titone. This bill has passed out of committee with unanimous consent, and we just need voices from Colorado outdoors enthusiasts like you to push it over the edge and make it a reality!

Whose Risk Is It?

Interested in learning how liability concerns impact recreation across the country? Do a deep dive into recreation, private land, and liability with our article “Whose Risk Is It?”

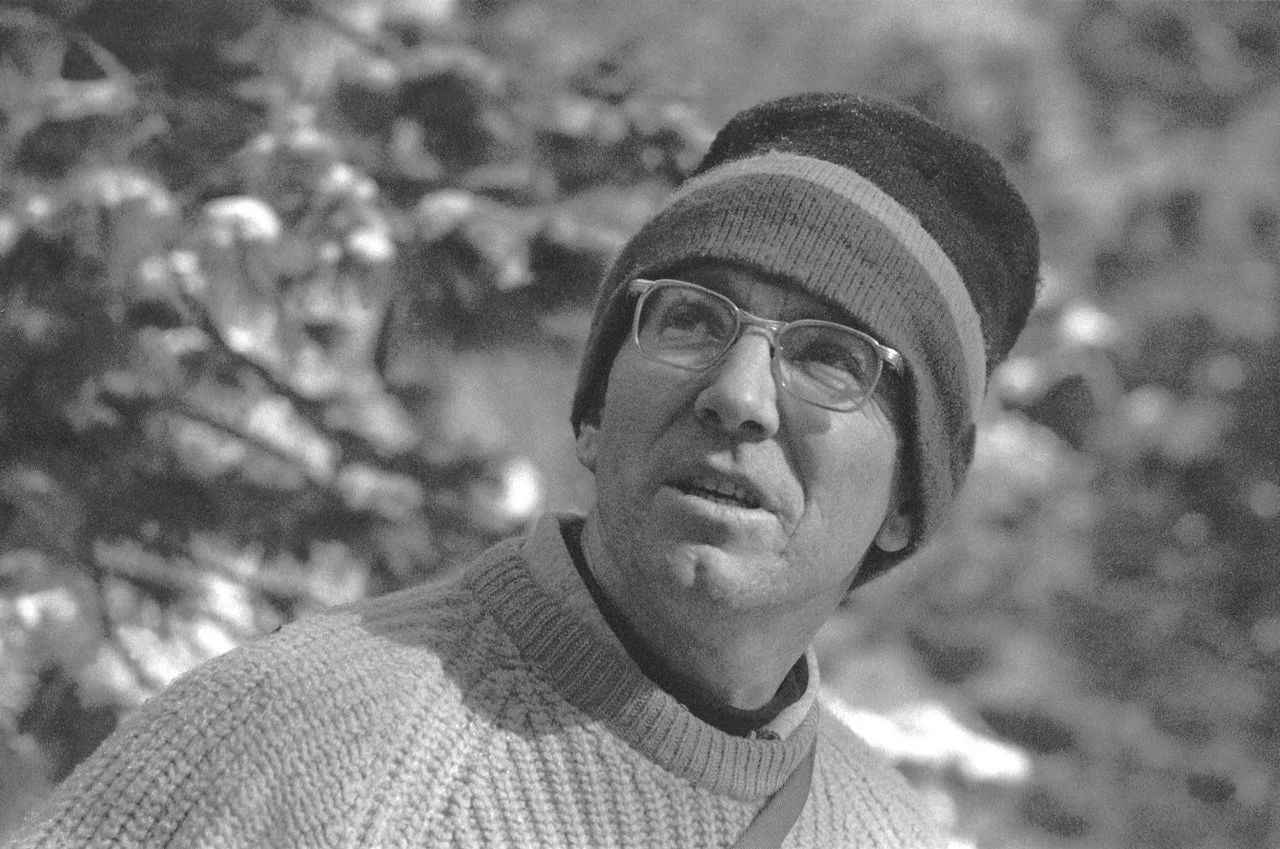

Legacy Series: Tom Frost

Tom Frost bivvying on El Cap. Photo by Royal Robbins, Courtesy of NACHA.

Tom Frost was one of the leading climbers of his generation, making important first ascents on El Cap, like the North America Wall and Salathé Wall. He was also a world-class alpinist and one of the main photographers who crafted a visual record of the Golden Age of Yosemite climbing, capturing the emotional imagery that would define a generation of climbers. Frost was at the forefront of defining clean climbing, often known for his enterprising and bold free climbing to avoid unnecessary bolting. He also engineered key climbing tools that we often take for granted today. In this interview with Tom Frost, we cover how he fell in with Royal Robbins, Chuck Pratt, Yvon Chouinard, and others; stories from his historic climbs; and how much he loved bivvying on the big walls of El Cap. Dive in to hear all this and more from this legend of climbing!

About the Legacy Series

A passion-project of AAC Past President Jim McCarthy and Tom Hornbein—themselves mountaineering legends by any standard—the American Alpine Club’s Legacy Series pays tribute to the visionary climbers who made the sport what it is today and stands as a commitment to securing their legacies.

Legacy Series: George Lowe, World Class Climber

George Lowe on Mt. Foraker.

Few Americans have had a climbing career anything like George Lowe’s. And we’re not the only ones who think so: The Piolets d’Or selected Lowe for their 2023 Lifetime Achievement Award. From first winter ascents of the Tetons’ highest peaks in the 1960s, Lowe moved on to cutting-edge climbs in Canada and Alaska in the 1970s, including the north faces of Mt. Alberta and North Twin in the Rockies and the Infinite Spur of Mt. Foraker in the Alaska Range. In the early ’80s, he was instrumental in the first ascent of the extremely difficult Kangshung Face of Everest. At age 79, George is still at it—climbing and skiing at a high level—and in this film he shares his thoughts about his long and illustrious climbing career and the humility and companionship it takes to survive and excel in the mountains.

A passion-project of AAC Past President Jim McCarthy and Tom Hornbein—themselves mountaineering legends by any standard—the American Alpine Club’s Legacy Series pays tribute to the visionary climbers who made the sport what it is today and stands as a commitment to securing their legacies.

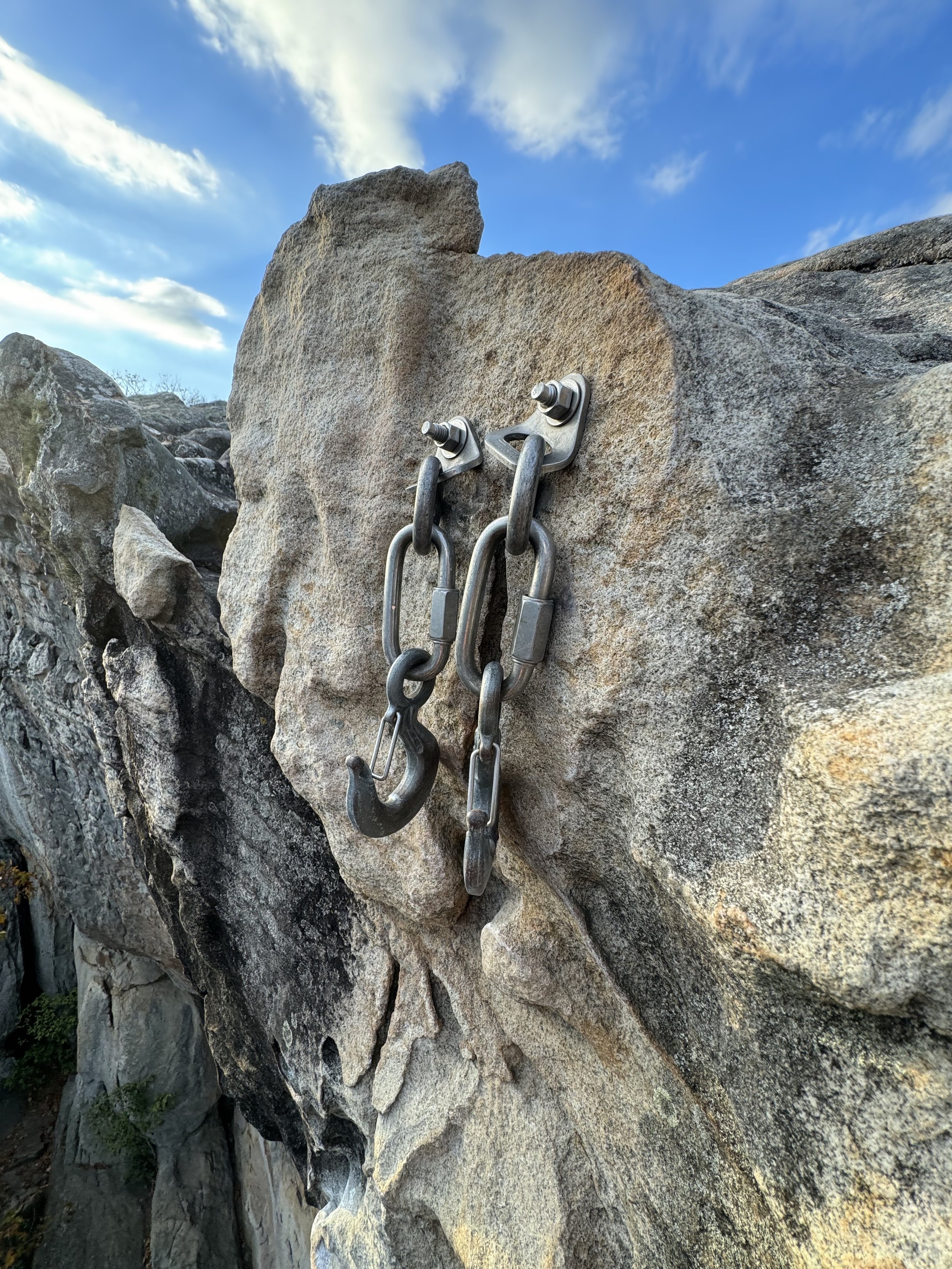

The AAC's Official Stance on the Proposed Fixed Anchor Guidance from the NPS and USFS

Photo by Sterling Boin.

Thanks to the diligent and extensive research and work by our policy director, Byron Harvison, the AAC has submitted the following public comments to the National Park Service (NPS) and United States Forest Service (USFS) respectively, about their proposed fixed anchor guidance in Wilderness Areas, on January 30th, 2024. Read the full statements by clicking each button.

An Excerpt:

“The AAC would like the National Park Service (NPS) and United States Forest Service (USFS) to adopt guidance which affirms that fixed anchors are not installations prohibited by the Wilderness Act and allow agency land managers to administer their areas in a similar manner with what had been established under NPS Director’s Order #41. In lieu of publishing such guidance, the AAC would ask that the NPS and USFS convenes a committee pursuant to the negotiated rulemaking process, or similar collaborative process, in order to address the issue of fixed anchors in Wilderness and implement guidelines following a committee report. The AAC reiterates that the MRA process is not only a technically incorrect tool for the evaluation of fixed anchors, but cannot be practically implemented due to agency underfunding and limited staffing, and such a process will inevitably lead to management by moratorium.

“The AAC will remain committed to instilling the ethos of maintaining wilderness character, utilizing the best low-impact climbing techniques and practices, and staunchly supporting appropriate recreation in Wilderness. The AAC is ready and willing to assist the NPS and USFS to deliver on their dual mandate of conserving Wilderness characteristics while also ensuring the benefit and enjoyment of the Wilderness for the broader public.”

Cathedrals of Wilderness

Three First Ascents from the Historic Roots of Wilderness Climbing

By Hannah Provost

Photo by Sterling Boin.

“ Wilderness areas shall be devoted to the public purposes of recreational, scenic, scientific, educational, conservation, and historical use.”

With much ado about whether the NPS and USFS will prohibit fixed anchors in Wilderness areas, the AAC thought we’d lean into one of our strengths—the immense amount of climbing history at our fingertips, thanks to nearly 100 years of documenting climbing through the American Alpine Journal and the AAC Library. Climbers have been utilizing and advocating for the responsible and thoughtful use of fixed anchors (including pitons, slings, and bolts) in what are now designated Wilderness areas since before the passing of the Wilderness Act in 1964. These stories from before Wilderness as we know it shows that climbers were thinking with careful judgment about the wilderness experience, and sparingly using fixed gear—if it was in fact crucial for the ascent or descent at all. Since then, recreation, including climbing, has been a major tenet of what the Wilderness Act aims to protect. The question is: how do fixed anchors fit into that commitment moving forward? And how do Wilderness climbing’s roots inform that future?

Check out the climbs below to get a sense of the roots of Wilderness climbing.

Check out this map, powered by onX, which features Mountain Project data in conjunction with Wilderness Area boundaries, to help visualize how climbing across the country is impacted by this discussion.

Take Action: Share Your Voice on the Proposed Wilderness Fixed Anchor Guidelines

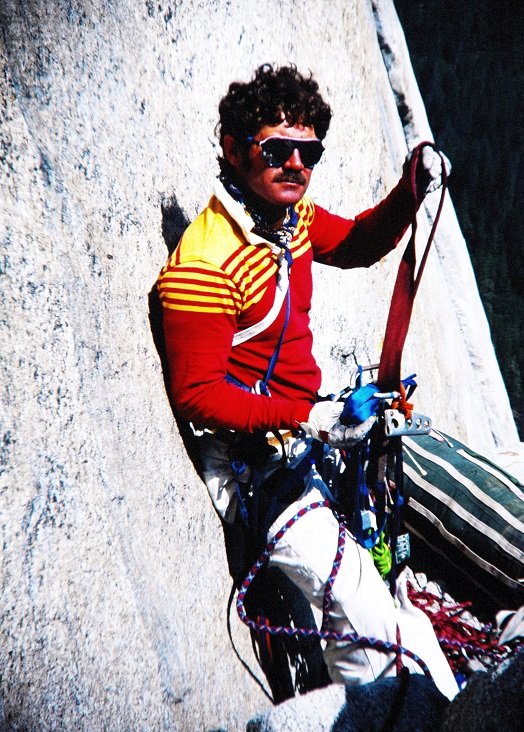

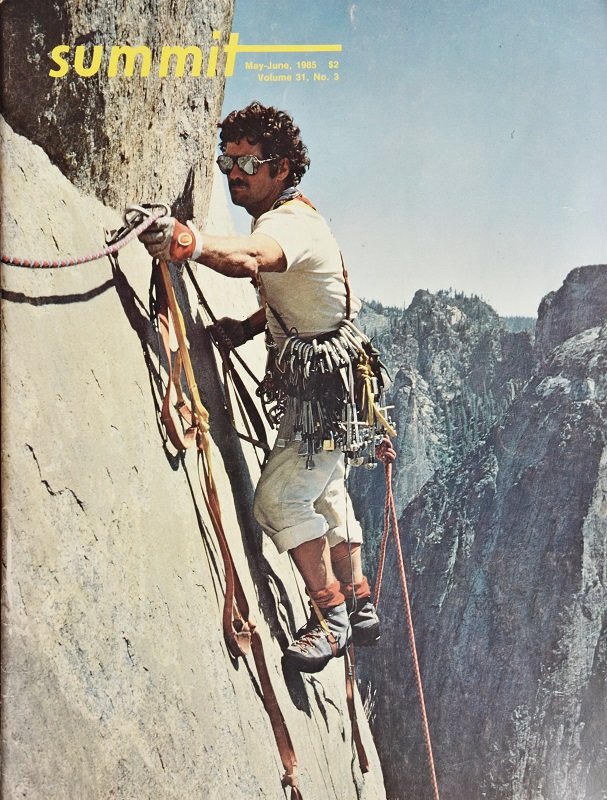

From the 1963 American Alpine Journal. Photos by Tom Frost, courtesy of North American Climbing History Archive.

The Salathé Wall, Yosemite Valley

Designated Wilderness in 1984

3500 ft (1061 m), 35 pitches, VI 5.9 C2, Robbins-Pratt-Frost, 1961

One of the longest routes on El Cap—and full of infamous wide cracks and ledges to bivvy on, The Salathé Wall is one of the iconic climbs in the world. The route has you balancing up the Free Blast, and shimmying up chimneys until you’re climbing the impressively steep headwall that makes everyone gape at El Cap. If you’re a badass, you can free it at .13b. But in 1961 Royal Robbins, Chuck Pratt, and Tom Frost were just excited to get up the thing, placing minimal fixed gear.

From the 1963 American Alpine Journal. Photo by Tom Frost, courtesy of North American Climbing History Archive.

In Royal Robbins’ 1963 report for the American Alpine Journal (AAJ), in which he recounts the first ascent done in 1961 and the first continuous ascent done in 1962, Robbins grapples explicitly with the bolting choices he and his team made as first ascensionists. Reflecting on the first continuous ascent, Robbins writes: “Tom [Frost] skillfully led the difficult section of the blank area where we had placed thirteen bolts the previous year. The use of more bolts in this area had been originally avoided by some enterprising free climbing on two blank sections and some delicate and nerve-wracking piton work. It would take only a few bolts to turn this pitch, one of the most interesting on the route, into a ‘boring’ walk-up.” Robbins and his peers were invested in finding those moments of “enterprising free climbing,” where they had to get creative and grit their teeth. Throughout his career, Robbins would have a lot of ambivalence about bolts—Salathé is a perfect example of that careful balance.

Though not directly or explicitly linked with his stance on fixed gear, it’s notable that Royal’s account of the continuous ascent of Salathé is intertwined with soulful reminiscing about nature. Robbins and his team considered Yosemite a special kind of remote nature, well before El Cap got a Wilderness designation with a capital W. Robbins ended his Salathé report: ”We finished the climb in magnificent weather, surely the finest and most exhilaratingly beautiful Sierra day we had ever seen…All the high country was white with new snow and two or three inches had fallen along the rim of the Valley, on Half Dome, and on Clouds Rest. One could see for great distances and each peak was sharply etched against a dark blue sky. We were feeling spiritually very rich indeed as we hiked down through the grand Sierra forests to the Valley.” This experience of vastness—of feeling the smallness of humanity within the quietude of nature, and that such experiences are enriching to the soul—is at the heart of what the NPS and USFS are trying to preserve, and which climbers like Robbins and all those who have followed him up El Cap have deeply loved about these places.

Layton Kor on the first ascent of The Diagonal, 1963. Photo from Kor’s book, Beyond the Vertical, photographer unknown.

The Diagonal, Black Canyon of the Gunnison

Designated Wilderness in 1976

2000’ (606m), 8 pitches, V 5.9 A5, Kor-McCarthy-Bossier, 1963

The Diagonal is in some ways an odd route to include here, because although it was important at the time, and excellent tales have been told about this first ascent, this route is rarely climbed today. It has the distinction of half a star on Mountain Project, and is known for the boldness required—which is particularly important to note in an area that already favors the bold. But we’re including it here precisely because of the climb’s historic nature, and how the first ascensionists—the magic team of Layton Kor, Jim McCarthy, and Tex Bossier—have articulated their thoughts on fixed anchors.

As a historic climb, The Diagonal contains multitudes. Layton Kor, who was the driving force behind the first ascent, was certainly known to be a singular kind of person. There was no one quite like him. In Climb!, his contemporaries describe this towering figure in awed terms: “Of his more forceful characteristics, those who knew Kor well during his climbing years say that he frequently exhibited the qualities of a man possessed. A driving inner tension gnawed at him. His way of escaping from this sensation was to be active in a way which totally occupied his mind and body. His climbs, pushed to the limit of the possible, served this function well.” When Kor legendarily quipped, staring up at the crux pitch on The Diagonal, that he wasn’t a married man, and perhaps he should take Jim McCarthy’s lead for that reason, behind the glint in his eye was that tension and drive. Kor did take the lead on the “horror pitch,” taking six and a half hours to complete it—and it’s still noted as one of Kor’s hardest leads in his career. After all, the team was trying for glory—attempting to find Colorado’s first grade VI, though it would turn out to be another grade V. It remains an iconic moment in climbing’s rich history of contemplating and pushing past our agreed upon limits.

Bossier indicated, in Kor’s book Beyond the Vertical, that the boldness that would come to characterize the climb was due in part to an intentional philosophical stance that the team made about the restrained use of fixed gear. Bossier writes: “The two major ethical dilemmas of the day were expansion bolts, and siege vs. alpine style ascents. We had taken oaths that the first grade six in Colorado deserved our commitment to a classic ascent. Despite knowing that we would pass through bands of rotten rock, we planned not to degrade our attempt with unnecessary bolting or extensive bolting.”

This sense of committing to good ethics and terms of engagement with the landscape is the backbone of the American idea of Wilderness, and embedded in the Wilderness Act, which defines Wilderness as “untrammeled,” “primeval,” and “undeveloped” landscapes, in which humanity is just a visitor. Though Kor, McCarthy, and Bossier weren’t meditating on nature in those explicit terms, their ascent too is wrapped in high-minded reflection on immersion in natural landscapes. After their wet bivvy, nature brought about a brush with awe that is so often what we seek in great, vast, wild adventures: “Next morning, as light became perceptible, we were engulfed in a dramatic whirlwind of dancing clouds. Shafts of light shone vertically upwards from the depths of the Canyon, while other masses swirled and skipped in wave patterns. We sat on our perches awed as light beams and rainbows mingled with mist. They were below us. They were with us—we could reach out and touch them. The clouds died as the power of the sun burned through and we began to take stock.”

No doubt waking up to this kind of light show—their position in the midst of it only possible because of this unique terrain—was part of the transformative experience of this climb. Bossier’s reflections demonstrate again that just as climbers of this time period were grappling with the appropriate boundary for the responsible use of fixed anchors, they were likewise attuned to how the landscapes they were climbing in shaped their experience.

Topo of D1, the first ascent of The Diamond, featured in the September 1960 issue of Trail and Timberline. AAC Library Collection.

D1, The Diamond, Rocky Mountain National Park

Designated Wilderness in 2009

1,010 ft (308 m), 8 pitches, V 5.7 A4, Kamps-Rearick, 1960

Though climbing lore often focuses on tales of breaking the rules and going against the grain, there has been a long history of climbers working within land agency regulations in order to gain sustainable access. The story of The Diamond of Longs Peak, one of the most sought-after walls in the country, is one such example. According to the recounting of the first ascent, published in the 1961 AAJ: “In 1953 a party organized by Dale Johnson of Boulder announced its intention of attempting an ascent of this wall, but was refused permission by the National Park. Since then the Diamond has been ‘off limits’ to climbers. Being thus restricted from the climbing activity going on elsewhere in the country, it gradually assumed the distinction of being the most famous unclimbed wall in the United States.” So when Robert Kamps and David Rearick received permission from RMNP to attempt to climb The Diamond in August of 1960, all eyes were on them.

September 1960 issue of Trail and Timberline, featuring an image from the first ascent of The Diamond. Cover photo by Al Moldvay of The Denver Post. From the AAC Library Collection.

The draw of the Diamond was certainly a sense of ultimate challenge. The altitude and remoteness of this striking wall was a key part of the adventure. Today, D1 is often overlooked, with more accessible lines like The Casual Route and Pervertical Sanctuary getting the most mileage, and lines like Ariana getting the most attention at the 5.12 grade. However, Mountain Project whispers suggest that well-rounded Diamond climbers consider it the best route on the Diamond. So unlike Kor’s The Diagonal, it’s historic and good climbing.

Rearick and Kamp’s three day ascent “was one more dent in the concept of the impossible.” Like many Diamond climbers even today, they battled the weather and a waterfall dripping on their belays and bivvy. But this encroachment of water seemed to be a reminder that though they may be conquering the wall, they were but a small creature in a wilderness that was ultimately untamable. Like so many other climbers recreating in such extreme natural environments, the ascent was inextricably linked to moments of sublime quiet. “The night was clear and we watched the shadows from the moon creep stealthily along the slope of Lady Washington below us and across the shimmering blackness of Chasm Lake. We both managed to doze for a few hours. Since the temperature stayed above freezing, the waterfall continued all night, occasionally splashing us. The altitude at this point was about 13,700 feet.”

Rearick and Kamps placed 4 expansion bolts in total—by hand, of course, which continues to be a requirement for new or replaced bolts in Wilderness—when all other ways of securing a belay were exhausted. This method and their tools had been explicitly reviewed and approved by the National Park beforehand, as a condition of their permission to attempt this famous feature. This incredibly important ascent was just the beginning of a revolution in climbing, as Godfrey and Chelton recount: “the concept of the impossible was seized roughly by the scruff of the neck and shaken up so as to be unrecognizable.”

***

As these three first ascents demonstrate, the roots of Wilderness climbing is often tied up with philosophies of restraint in use of fixed gear, spiritual connection with nature, pushing the limits of the sport, and prioritizing boldness without being unsafe.

That was Then…This is Now…

Much of the discussion around fixed anchors in Wilderness within the climbing community has simplified and erroneously associated the concept of fixed anchors with grid bolting or sport climbing. Some people are kicking around the idea that the only climbing that should happen in Wilderness is the purest kind, like “back in the day”—suggesting that absolutely no fixed gear was used “back in the day.” The history of these iconic Wilderness climbs shows that this narrative is full of misunderstandings. Even when the best climbers of the day refused to “degrade” their ascents with unnecessary bolting or fixed gear, they did apply these tools when necessary for safety. Evidently, Wilderness climbing’s roots lie in a philosophy of responsible and restrained use of fixed anchors to facilitate meaningful experiences and inspire advocates of Wilderness. Now the question is, what is Wilderness climbing’s future?

You can help decide. Share your thoughts on the proposed fixed anchor guidance from the NPS and USFS before January 30, 2024.

Resources:

This article was only possible thanks to the depth of resources from the American Alpine Club Library and historic records from the American Alpine Journal. Want to delve into our extensive historic climbing archives and guidebook library? Check it out.

“The Salathé Wall.” American Alpine Journal. 1963.

“Salathe Wall.” Mountain Project.

Beyond the Vertical by Layton Kor

“The Diagonal.” Mountain Project.

Climb! Rock Climbing in Colorado by Bob Godrey and Dudley Chelton

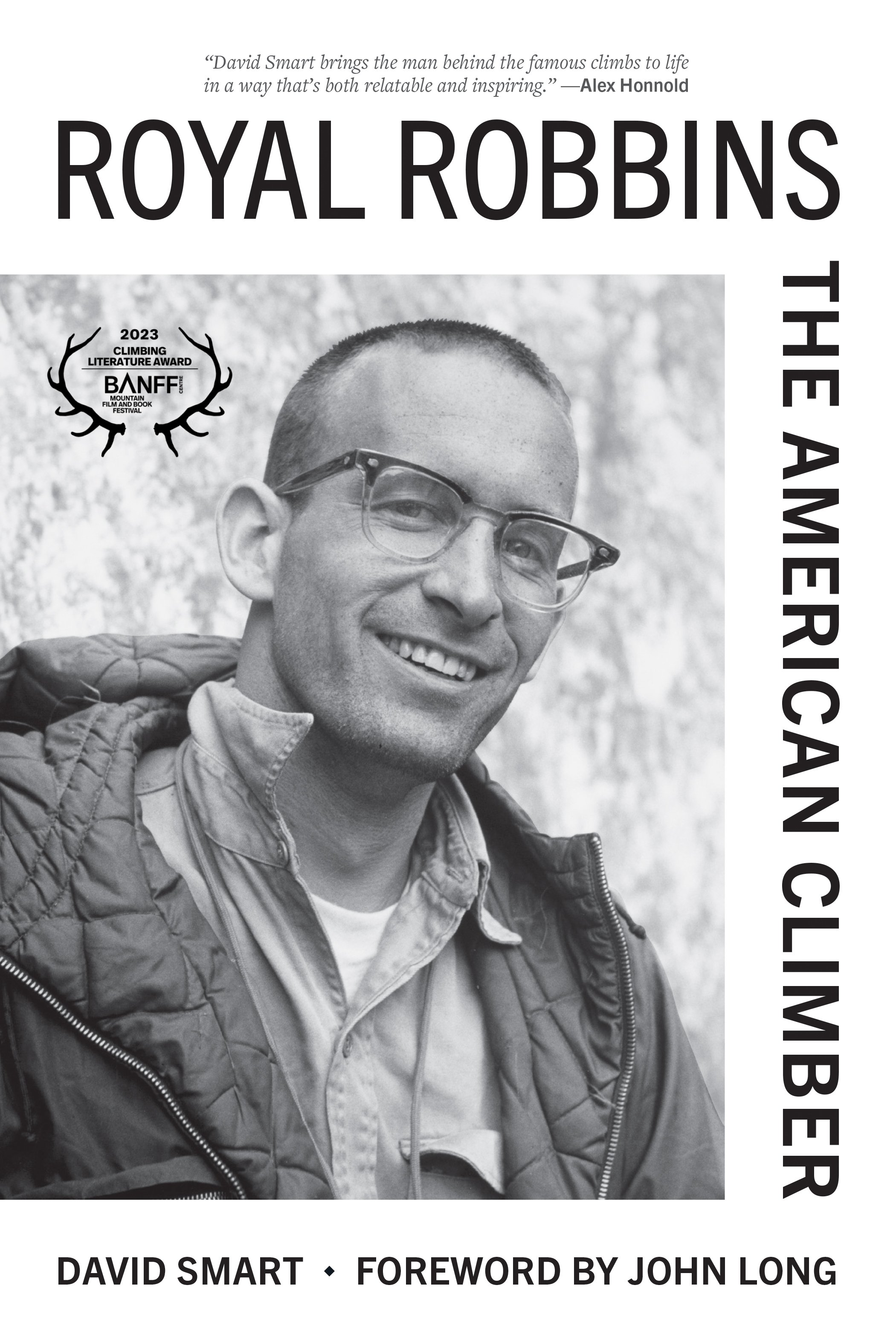

Royal Robbins: The American Climber by David Smart

The Black: A Comprehensive Climbing Guide to Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park by Vic Zeilman

“The First Ascent of the Diamond, the East Face of Longs Peak.” American Alpine Journal. 1961.

“D1” Mountain Project.

The Line — January 2024

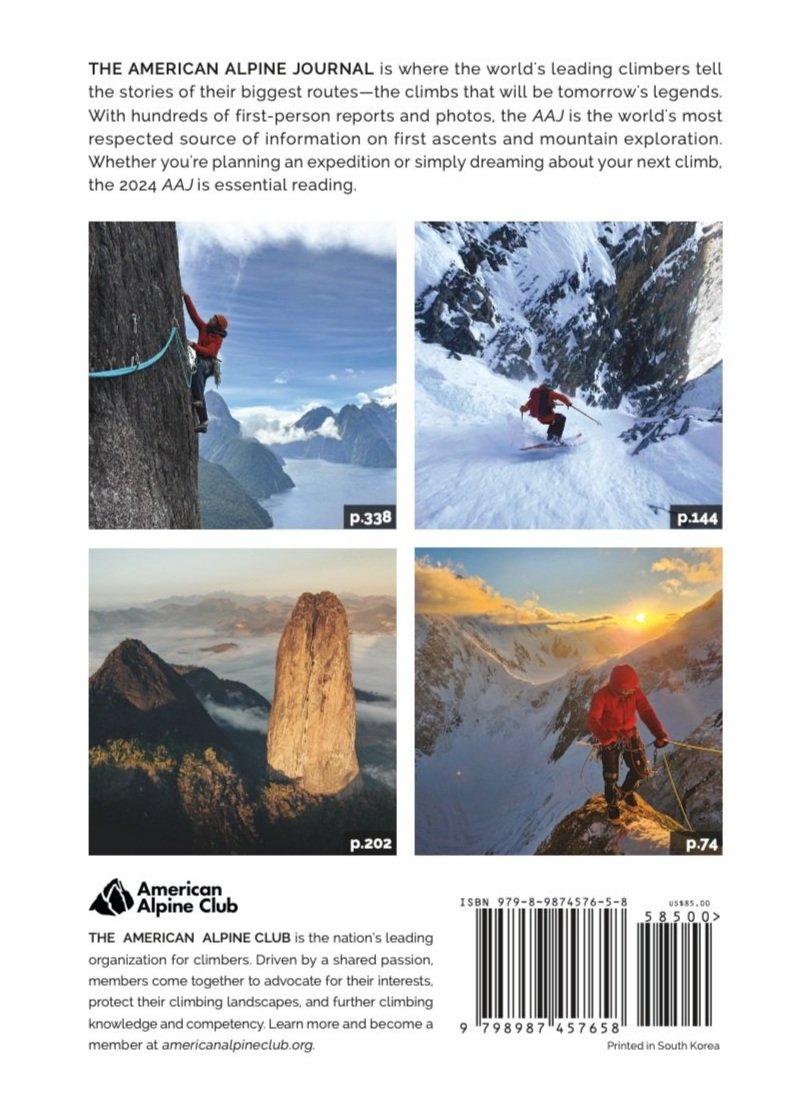

In this month’s edition of The Line, we bring you two brand-new AAJ stories—plus a vintage report that’s had a fresh update.

Suraj Kushwaha leading the final corner on Fissure in Time. Photo: Nikhil Bhandari.

COOL CLIMBS IN NORTHERN INDIA

Rathan Thadi, near Manali, India. Photo: Suraj Kushwaha.

Supported by an AAC Live Your Dream Grant, Suraj Kushwaha from Vermont and Nikhil Bhandari from Hyderabad, India, explored a beautiful granite dome near Manali in northern India. Last spring, Kushwaha had attempted a route on the 4,600-meter formation, dubbed Rathan Thadi Dome, but melting snow soaked the rock and halted the effort. Armed with the lessons from that experience, he returned with Bhandari in October and climbed two beautiful rock routes: Rathan Thadi Direct (6 pitches, 5.11-) and Fissure in Time (6 pitches, 5.10 A2 M2). Kushwaha said the latter would go free at about 5.12-. The two also found some quality bouldering in the valley, the highlight of which was Tehelka (“Chaos,” V6).

In addition to winning an AAC grant, this expedition was the capstone project of Kushwaha’s participation in the Scarpa Athlete Mentorship Program (supported by Mountain Hardwear), which aims to help athletes from historically marginalized communities take their game to the next level. You can download Kushwaha’s complete report on the Rathan Thadi climbs at the AAJ website.

Working on Tehelka (V6). Photo: Kiran Kallur.

THE TRENCH CONNECTION

In early March 2023, Dylan Miller, Seth Classen, and Keagan Walker made a rare winter ascent of the Main Tower (6,910 feet) in the Mendenhall massif, via the standard route up the west ridge. A few weeks later, Dylan and Seth returned with Alex Burkhart and Cameron Jardell for an even more ambitious project: a new route up the south face.

Top: Seth Classen during the descent from the top of the Main Tower after making the first ascent of The Trench Connection. Bottom: The new line. The descent was to the left. Photos: Dylan Miller.

Starting in the afternoon of March 26, the quartet made the 10-mile, seven-hour approach on skis and reached the base of Main Tower at nightfall. Although the temperature soon plummeted, they had planned a nighttime ascent to minimize the solar effect on the deep snow they’d be climbing. Hours later they reached the top of Main Tower after completing The Trench Connection (1,600’, IV AI3 85°). They descended the normal route, using the anchors from their winter ascent three weeks earlier, and skied back toward town, reaching the cars by 10 a.m. on March 27 after a long, frosty night in the Alaskan wilderness. Read Dylan’s story at the AAJ website.

HISTORY: BAINTHA BRAKK II

Baintha Brakk II, the 6,960-meter neighbor of the famous Baintha Brakk (The Ogre) in the Karakoram, was first climbed in 1983 by a Korean team, by the northwest buttress. The AAJ report was scant and, it turns out, had some errors. These have now been corrected thanks to Kim Dong-soo from Korea, who also provided some historical photos from the climb. Two members of the 1983 expedition reached the summit: Lim Deok-yong and Yoo Han-gyu. During the final push above Camp 3, the two had to bivy in a snow cave at 6,800 meters without sleeping bags before carrying on to the top. Read the updated report here.

Climbing at 6,400 meters during the 1983 first ascent of Baintha Brakk II (a.k.a. Ogre II). Photo: Korean Ogre II Expedition.

Baintha Brakk II as seen from Baintha Brakk, showing the line up the northwest buttress attempted in 2015, very close to the 1983 first ascent of Baintha Brakk II by a Korean expedition. Photo: Kyle Dempster.

Many American climbers will remember Baintha Brakk II as the peak that Scott Adamson and Kyle Dempster from Utah attempted twice by the north face. Tragically, they disappeared during their second attempt, in 2016. One year earlier, Marcos Costa (Brazil) and Jesse Mease (USA) made a four-day, alpine-style attempt to repeat the Korean route on Baintha Brakk II, finding very difficult climbing before retreating at 6,700 meters. Although conditions undoubtedly were different three decades after the first ascent, the photos from 2015 are ample testimony to the difficulty of the ground the Korean team climbed in 1983.

Most reports older than 2010 in the AAJ online archive are not accompanied by any photos. If your climb was published in the AAJ before 2010, we invite you to submit photos to update our online stories and complete the historical record. Contact us at [email protected].

THE CUTTING EDGE PODCAST: WHITE SAPPHIRE

For the final episode of the Cutting Edge podcast’s 2023 season, we interviewed Christian Black, Vitaliy Musiyenko, and Hayden Wyatt about their new route on White Sapphire, a peak in northern India’s spectacular Kishtwar district. Supported by a Cutting Edge Grant from the AAC, the three climbers put up Brilliant Blue (850m, AI3 80°M7+), probably making the third ascent of the 6,040-meter peak. Two of the three climbers had never been to the Himalaya, and this interview captures their wide-eyed enthusiasm, as well as their ability to go with the flow—a critical element for success in the Greater Ranges. Listen here.

Sign Up for AAC Emails

The Line is the newsletter of the American Alpine Journal (AAJ), emailed to more than 80,000 climbers each month. Find the archive of past editions here. Contact Heidi McDowell for sponsorship opportunities. Questions or suggestions? Email us: [email protected].

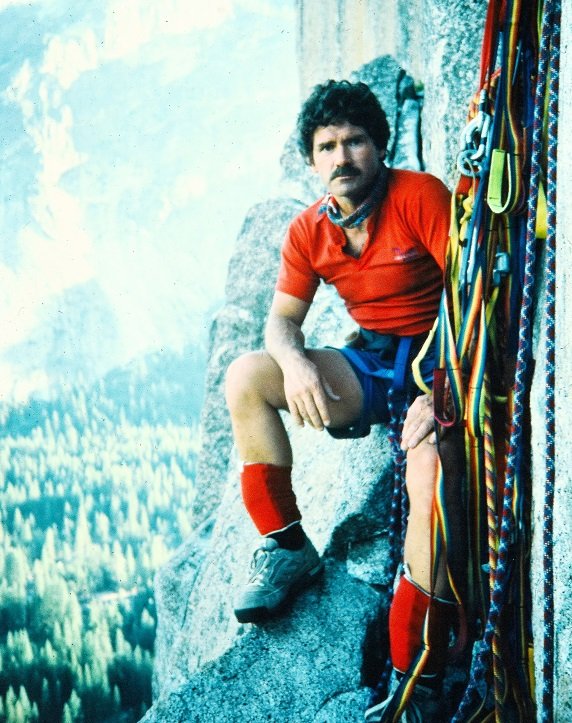

CLIMB: Tom Evans and Two Decades of Reporting on El Cap Climbing

Tom Evans on El Cap back when he was climbing it instead of reporting on it.

New episode of the American Alpine Club Podcast with legend Tom Evans:

Tom Evans is the creator of the El Cap Report. He started out taking photos of all the climbers he’d see on El Cap, and got tired of answering questions about who was doing what and how X ascent was going. So he innovated. He started posting a daily report, accompanied by his photos, of what was happening on El Cap during the main Yosemite climbing season—and he since has crafted a legacy of 22 years of documenting “the center of the universe”—El Cap climbing. With his recent retirement from the El Cap report, we decided we wanted to celebrate this legacy, and hear all his thoughts on the climbing history he’s documented, witnessing accidents and rescues, what’s next in El Cap climbing, the impact of social media in the Valley, and what motivated him in the first place to create the El Cap report. Dive in to get to know one of the legendary names from the El Cap bridge scene—a conversation just for you, unique in all the world!

Tom Evans in Action: Climbing and Documenting the “Center of the Universe”

The Prescription—January 2024

A note from the editor of Accidents in North American Climbing: I’m writing this from the AAC Hueco Rock Ranch in Texas. Here, the season is in full swing for what some say is the best bouldering on the planet. While often regarded as relatively risk-free, bouldering can be plenty dangerous. This month we feature a reminder from Joshua Tree National Park.

The Hidden Valley Area of Joshua Tree National Park. This popular expanse holds a vast number of classic boulder problems, including White Rastafarian (V2-3,PG-13). Photo: Wikimedia Commons NPS/Hannah Schwalbe.

Bouldering Fall | Insufficient Pads

California, Joshua Tree National Park, Hidden Valley Area

On November 9, 2023, Gibson McGee (19) was bouldering on White Rastafarian, a V2 (often graded V3) highball that has been the scene of many accidents. He fell from near the top and struck the ground, shattering his L1 vertebra, the highest bone in the lower back.

Though Mountain Project describes White Rastafarian as “one of JTree’s finest (problems),” the climb is 25 feet tall—more a short route instead of a boulder problem. After the midpoint crux, the climber is faced with a tricky mantel topout.

Victor Pinto topping out on the classic White Rastafarian. John Long, who did the first ascent of this iconic highball with John Bachar, wrote of their experience in Climbing magazine, “Once we passed a precise but invisible line, we were soloing, plain and simple.” Photo: Victor Pinto.

McGee wrote to ANAC, “I was heading to Joshua Tree for the weekend, and I was planning on meeting a group who were coming in the following morning. After setting up camp, I went to go climb the nearby White Rastafarian. I had previously attempted it but fell at the crux (15 feet off ground). I was fine with no injuries.” McGee laid out three crash pads, set up a video camera to record himself, and started up the route.

Graphic Video Warning

At Accidents in North American Climbing we refrain from publishing gratuitous depictions of injury. However, to convey the real risks of an activity that many people consider relatively risk-free, we are providing a link to Gibson’s Instagram account:

See his video here.

“I got to the top of the route (about 25 feet off ground) and was too pumped to do the ‘easy’ mantel onto the top of the rock. I looked down and decided I could drop safely. I dropped, but when I hit the ground, I ended up shattering my L1 vertebra. I then army crawled (using arms and upper body to cross the ground) to the nearby Hidden Valley Campground, where I got help and was transported by ambulance to High Desert Medical Center.”

McGee is currently recovering. He wrote, “While I am eager to be able to climb again, healing physically and mentally from this fall will take me quite some time. I was very fortunate looking back on the possible injuries I could’ve sustained.”

Analysis

Bouldering is inherently dangerous, and highball problems particularly so. On Reddit, un poco lobo posted, “Was chatting with a park ranger who said they see more accidents on WR (White Rastafarian) than pretty much all other routes/problems combined.”

A Similar Accident

For another Joshua Tree bouldering accident involving inadequate pad placement, click here.

McGee had been consistently climbing outdoors for one year prior. He recalls, “I saw White Rastafarian the first week I started climbing. It has always been a dream for me to do it.” His pad placements were in the right place and he landed cleanly—no part of his body struck exposed ground. While multiple pads are great idea, an evenly distributed second layer of pads might have saved McGee from a trip to the hospital. Covering gaps between pads with a thin “slider” pad also would have provided additional safety. McGee mentioned, “I should’ve brought a buddy and stacked bouldering pads.”

Keep ‘Em On The Pad!

In bouldering, spotting is the norm. On highballs, though, spotters can be extraneous as the impact forces of a falling climber can be equally harmful to the spotter. See a fall from the same problem that came close to injuring the spotter here.

While spotting highballs is more art than science, the general rule is to ensure the falling climber stays on the pad after impact. Guaranteeing that the climber impacts the pad itself is part of good pad placement. A spotter should also protect the head and neck from impacting bare ground or surrounding obstacles. Another good rule to follow is to never fall above the 20-foot mark. Be open to using a top-rope to practice the problem. John Gill himself was a big exponent of top-roping.

Finally, Joshua Tree has a well-earned reputation for tricky climbing and a long learning curve. As always, different climbing areas have special characteristics that grades do not convey. Be conservative and risk-averse as you learn the peculiarities of any area. Wrote McGee, “I have bouldered in Joshua Tree four or five times. The grading is much, much harder than what you might think. I let the number (V2-3) get in my head rather than trusting the true difficulty of J Tree grades.”

(Sources: Gibson McGee, Mountain Project, and Climbing magazine.)

Clarification and Reflection on Michael Spitz Free Solo Accident

In the 2023 ANAC, we reported on the death of free soloist Michael Spitz. Recently, Brian Gillette, a close friend of Spitz, reached out to correct some inaccuracies in our report. In his letter to ANAC, Gillette filled some gaps in our understanding of the accident, while offering some thoughtful words on risk.

A short excerpt, “In the year before his death, Mike's free soloing had accelerated from an occasional outing to a nearly weekly activity. The more he free soloed, the more I watched his perception of the risks become disconnected from the reality of climbing. Mike had also been surfing a heavy swell in the days leading up to his death. When I spoke with him the night before, I thought he sounded tired and told him to take it easy. He told me he planned to climb for the day and head home. From what I can tell, soloing Illusion Dweller was a last-minute decision. He might have been more tired than he realized. It might explain why a small slip caused him to fall. Mike's last-minute decision also meant that he wasn't prepared in any way for a potential accident, even a minor one.”

Read the original report and Brian Gillette’s full letter here.

Sign Up for AAC Emails

The Line — December 2023

Lots of rock: The gorgeous view from a beach campsite along Khor Ash-Sham. Photo: Marius Rølland | @unrealmarius

THE NORWAY OF ARABIA

“From our campsite at the edge of the Khor Ash-Sham (Ash-Sham Fjord), on yet another deserted white-sand beach, we watched the sun sink low over the Strait of Hormuz. A single thought occupied our minds, and Aniek was the first to put it to words: ‘I don't want to leave tomorrow.’”

Alan Goldbetter, who wrote this passage for AAJ 2024, spent eight days last January with Aniek Lith and Marius Rølland exploring Khor Ash-Sham in the Musandam Peninsula of Oman: “kayaking with dolphins, wading shin-deep through bioluminescent algae, climbing multi-pitch routes on virgin limestone, and giggling the nights away under a shimmering, star-filled sky.” Their two new routes, each 5.10 and more than 1,000 feet long, were the first recorded roped climbs in the fjord. Read Goldbetter’s AAJ 2024 report to learn more.

Evening fun: After a day scrambling a ridge on Khor Ash-Sham fjord’s north side, the team prepares to bivy. Photo: Marius Rølland |@unrealmarius.

CLIMBS IN CANADA’S ARJUNA SPIRES

Daniell Councell moving up easy ground near the start of the Quartz Arête, the first known route up Nakula Spire, whose summit towers high overhead. Photo: Andrew Councell.

Starting the upper buttress on Nakula Spire. Photo: Andrew Councell.

Heli-skiing guide Andrew Councell had ogled the rocky peaks around Bella Coola, British Columbia, for years while flying into the mountains to ski, but the few roads and desperately steep hillsides in the area severely limit summertime access. “Finally,” Councell writes in an AAJ 2024 report, “in a culmination of years of desire to climb these mountains, mixed with a fatalistic shrug toward my bank account, I planned an exploratory trip with my brother Daniel.” A 10-minute helicopter flight landed them at a luxurious base camp by the Arjuna Glacier.

The result was the probable first ascent of two formations in the Mt. Arjuna massif, along with a handful of shorter routes and a rare climb of Arjuna itself. The highlight was the Quartz Arête on the north side of Nakula Spire, a beautiful buttress with mostly moderate climbing and a crux of 5.9. “My hope,” Councell writes, “is that continued development of climbing in the Bella Coola backcountry will encourage fellow adventure seekers to discover this untapped arena.”

PUNCHING A ROUND TRIP TICKET

This month’s Cutting Edge podcast interview with Matt Cornell, Jackson Marvell, and Alan Rousseau, about their alpine-style new route up the north face of Jannu (Kumbhakarna) in Nepal, is understandably one of the show’s most popular episodes in years.

One thing we didn’t get to in the hour-long interview is the origin of the new route’s name, Round Trip Ticket, which has an interesting and telling backstory. In 2007, Valery Babanov and Sergey Kofanov climbed the west pillar of Jannu, a remarkable climb in its own right (also climbed alpine-style). A decade later, Kofanov wrote in an Alpinist magazine Mountain Profile about Jannu: “Perhaps someday, a pair will climb a direct route on the north face in alpine style, but they’ll need to accept the likelihood that they’re buying themselves a one-way ticket.” As you’ll hear in our interview, the three American climbers’ planned itinerary was round-trip all the way.

The Line is the newsletter of the American Alpine Journal (AAJ), emailed to more than 80,000 climbers each month. Find the archive of past editions here. Interested in supporting this online publication? Contact Heidi McDowell for opportunities. Questions or suggestions? Email us: [email protected].

Sign up for AAC Emails

“The Line” is Supported By

Measuring Success in the Mountains

PC: Lindsey Hamm

A Story from the Cutting Edge Grant and the McNeill-Nott Award

By: Sierra McGivney

In July of 2023, Lindsey Hamm, Rhiannon Williams, Stephanie Williams, and Thomas Bukowski traveled to the Charakusa Valley in the Karakoram to attempt routes on Naisa Brakk (~5,200m) and Farhod Brakk (~5,300m). To attempt these objectives, Hamm received the American Alpine Club's McNeill-Nott Award and $6,000 from the Cutting Edge Grant. This was Hamm’s second trip to the Charakusa Valley. In 2022, she, Dakota Walz, and Lane Mathis established a first ascent on a formation between Spansar Brakk and Naisa Brakk (which they named Ishaq Brakk): Pull Down the Sky (15 pitches, 5.11 R). In 2023, she defined success a little differently.

“I think there were a lot of lessons learned,” remarked Lindsey Hamm from a coffee shop in Moab. She's been enjoying climbing in the desert; today is her rest day.

She had returned from the Charakusa Valley a couple of months ago without accomplishing the FAs she had dreamed up. This year, her crew went in with two objectives, and they split up in two teams to make their respective attempts. But ultimately, the weather was against them, and it rained 22 of the 30 days they were in the valley.

PC: Lindsey Hamm

The team desperately wanted to climb, but the weather was a big factor. When they did attempt a line, they would climb for an hour, bivy, wait out the rain, and then climb. They were in this constant mode of stop-and-go that was not sustainable.

Hamm and Bukowski attempted a route on the Northeast Spur on Farhod Brakk. They were shut down due to objective hazard and need for potable water. The two had only planned for two or three days and ended up being out for about four days. Then bad weather moved in.

“I think it was a bad season for rock climbing,” said Hamm.

This was another lesson learned: Big-wall climbing is better later in the season. She chose to go in July because she wanted to attempt both alpine and rock objectives. The environment is so different from one peak to the next that you could attempt both alpine and rock objectives during this time of the year.

PC: Lindsey Hamm

“I'm really learning the place,” said Hamm. Hamm is an AMGA Certified Rock and Alpine Guide, and an Apprentice Ski Guide, but she believes there is always more to learn, especially in alpinism.

In addition, Hamm and another teammate dealt with altitude sickness. This was something new for Hamm. She had never experienced it to the extent she did on this trip. On one of the climbs, she was breathing heavily. She had to take a moment to feel everything and then “get her shit together.” According to Hamm, her group’s effort to help each other out when they were sick was a highlight of their climbing.

Hamm’s team wasn't the only group stifled by the rain. Base camp, which sits at 14,321 feet, became a hub of climbers waiting for good weather windows. Groups played volleyball together, hosted movie nights, and played Settlers of Catan. Hamm was very social; she went to other campsites, hung out with different people, and got to know everyone. She read, worked out, and cooked with the porters.

Hamm took it in stride—the trip wasn't a negative experience; things just weren't aligning. With each passing season, she is becoming more and more dialed. Last year, Hamm and Dakota Walz started a line, but they didn’t get to finish putting it up or cleaning it—they only completed one pitch. This year, Hamm got back on that first pitch with S. Williams, R. Williams, and Bukowski, and climbed five more pitches to link into the Southwest Ridge, first put up by Steve House, Marko Prezelj, and Vince Anderson in the early 2000. Their “sit-start” to the Southwest Ridge is called Stop Talking (six pitches, 5.12-). Their plan was to link into the Southwest Ridge and then break off into the west face and put up a new route, but once again, rain and thunder turned them around. Later, S. Williams and R. Williams attempted Stop Talking ground up, but were again foiled by rain.

On expeditions, climbing isn't the only focus for Hamm. She believes in having a positive impact on the local community. The team brought over school supplies for the Hushe Valley, which they distributed among three schools in the area. In addition, Hamm set up a GoFundMe that goes towards the Iqra Fund, which helps Pakistani women achieve their master’s degrees. Hamm and the team met some of the women who benefited from the fund. The team got to see their faces, hear their voices, and see how they lived. Facilitating and helping with these women’s education meant so much to Hamm.

“I think one of the biggest highlights was meeting those women,” said Hamm.

PC: Lindsey Hamm

She got to see many of the same porters and guides she worked with last year. They were as happy to see her as she was to see them. Despite the language barrier, the experience was like reuniting with old friends. She gave away a lot of her Rab equipment, including sleeping bags, to her porters and guides. It’s important for her to give back to the community that is helping her achieve her goals in the mountains.

“It [provided] so much validation about how much of the connection I built with people,” said Hamm.

Since returning to the United States, Hamm has been looking toward the future, analyzing what she can do better next time.

“I'm going back next summer,” said Hamm, with a big smile on her face. “I already told Jack Tackle.” Tackle chairs the AAC’s Cutting Edge Grant committee, which decides the fate of grant applications.

She will train hard and try her best to get funding without forcing anything. She has 170 lbs. of stashed gear waiting for her return. She's definitely going back. Right now, she is focusing on the next couple of months. Hamm is going through the IFMGA guide certification process—this season, she will take her final exam. She’s still processing this summer’s trip and reflecting on what she can do better next time. Most importantly, she’s living for today.

Fixed Anchors in Wilderness 101

YOUR TOPO TO THE MOST IMPORTANT CLIMBING POLICY ISSUES HEADING INTO 2024

Paul and Marni Robertson on “Moonlight Buttress” (5.12d), Zion National Park, Utah. Photo by AAC member Jeremiah Watt.

We know climbing policy can be complicated. That’s why we’re giving you the bite-sized answers you need about the key policy topic right now: fixed anchors in Wilderness. Dive in to get a concise understanding of the lay of the land: What is the PARC Act? What does the National Park Service and Forest Service have to say about fixed anchors and climbing? How does it relate to each other? What can climbers do to share their perspective on Wilderness climbing? We break it down and give you an opportunity to share your thoughts on fixed anchors in Wilderness Areas.

Click and scroll to explore…

The AAC and Nina Williams have been advocating for climbers in DC!

Hear from Nina Williams about what it was like to advocate for the climbing community, and what motivates her to take action and use her passion for climbing to make a difference.

Photo by AAC member Andrew Burr. Scott Willson on the “East Buttress” (5.10b) of El Capitan, Yosemite National Park, California.

TAKE ACTION: Share Your Voice on the Proposed Wilderness Fixed Anchor Guidelines

Photo by AAC member Andrew Burr. Scott Willson on the “East Buttress” (5.10b) of El Capitan, Yosemite National Park, California.

Climbers have been staunch defenders and careful stewards of our wild landscapes in national forests and national parks since before the Wilderness Act of 1964. At the American Alpine Club, we want to ensure climbers' voices are heard on this issue. Let the National Park Service (NPS) and United States Forest Service (USFS) know where you stand on the responsible use of fixed anchors in Wilderness by submitting your comments to both agencies before January 16, 2024.

What are the recent Forest Service and National Park Service climbing guidance proposals?

These two separate and distinct climbing guidance proposals inform how these agencies would manage climbing within their respective areas. These proposals include a novel interpretation of fixed climbing anchors as prohibited, which reverses over 60 years of precedent in Wilderness located in national park and national forests, respectively.

What might these proposals mean for climbers?

By reclassifying fixed anchors (including slings, bolts, pitons, and ice screws) as prohibited installations in Wilderness and national forests, existing and new fixed anchors would require analysis and approval by the local land managers. This shift has the potential to impact historic climbing routes in iconic areas, as well as stifle future route development and fixed anchor maintenance for safety.

Ready to speak up for Wilderness climbing?

Below is a template to get you started on your NPS and USFS public comment. Please personalize with your own experience!

“As a climber, I want to ensure the safe and responsible use of fixed anchors in [Wilderness/national forests] remains available to the climbing community. I respect and advocate for the responsible use of Wilderness areas and believe that fixed anchors can be a component of a sustainable Wilderness experience. Please revise your climbing guidance to reflect the practice and precedent of the last 60+ years–that fixed anchors for climbing can be used, replaced, and maintained in designated [Wilderness/national forest] areas.”

Want to learn more about the NPS + USFS proposals, the PARC act, and AAC’s recent actions on Capitol Hill?

CONNECT: The FKT of the Rainier Infinity Loop, In Memory of A Friend

Abby Westling and Kiira Antenucci were devastated to lose their friend Luke to a climbing accident in 2022. But as they learned to cope with this tragedy, they began to dream up something big. In July of 2023, Kiira and Abby set out to attempt The Infinity Loop, an epic endurance test piece that summits Rainer twice and circumnavigates the mountain via the Wonderland Trail. The two have extensive experience as guides on Rainier, and have submitted dozens of times, but this challenge would push them to their limits. They also wanted to do it in memory of their friend, and raise money for the AAC’s Climbing Grief Fund (CGF), which had supported them in the early stages of their grief process. Dive into this episode to hear the full story of how they set the female Fastest Known Time (FKT) on the Infinity Loop, the emotional ups and downs of such a massive challenge, why the Climbing Grief Fund means so much to them, and the impact of their incredible work in fundraising for the CGF.

New Route on White Sapphire

Cerro Kishtwar (center), White sapphire (right). Photo by Vitaliy Musiyenko.

A Story from the 2023 Cutting Edge Grant

By: Sierra McGivney

On October 6, 2023, Christian Black, Vitaliy Musiyenko, and Hayden Wyatt summited White Sapphire, a 6,040m peak in India's Kishtwar Himalaya. The new route was named Brilliant Blue (850m, AI3, M7+). To attempt this mountain, the team received $8,000 from the American Alpine Club's Cutting Edge Grant, made possible by Black Diamond. They climbed the route free and in alpine style. This is the third ascent of White Sapphire.

Pack mules descending the valley on our hike to basecamp. Photo by Vitaliy Musiyenko.

AAC: In 2022, you received the Live Your Dream Grant to attempt a line in British Columbia on Mt. Bute. How did you transition from a Live Your Dream–style expedition to a Cutting Edge–style expedition in just a year?

Christian Black: The funny thing was we just needed an idea. Expeditions are challenging to plan. It all came from our friend giving us the idea—something to dream about, on the other side of the world as opposed to in America or Canada.

AAC: White Sapphire has seen two first ascents previously, via the west face in 2012 and the south face in 2016; how did you choose this peak and, more specifically, the line?

CB: I've always struggled to plan what to do in an area I haven't been to. There's just too much information out there. The story is that I met a guy who had spent his whole life going on expeditions. He had a whole list of unclimbed things he never got around to. He was trying to find people to do them. And he approached me and said: You're a big-wall climber with alpine climbing experience. You should check out this peak. I've got photos of it, and it's pretty cool looking. So, the original intent was to climb the big-wall rock face on White Sapphire, knowing that we had to be flexible to the conditions. We ended up climbing more of an alpine route because we went later in the season, and it had snowed and gotten cold. But to answer your question, it was a gift from someone who has done a lot of cutting-edge expeditions and is out of the game now. He had said: I'm aged out and happy to pass on the torch of ideas if you're interested in going to the Himalayas. The Himalayas are such a large place; you'll never know what to do unless you go once, so you just need a reason to go.

Hayden starting a simul-block up midway up the steep snow and ice of the lower section of the route. Photo by Christian Black.

AAC: Who gave you the idea?

CB: It was Pete Takeda [the editor of Accidents in North American Climbing.] I'm like a bad historical knowledge climber, so I didn't know much about him until later. But, I mean, obviously, he's legendary.

AAC: What type of climbing did you encounter on White Sapphire?

CB: We first encountered 2,000 vertical feet of steep snow and ice with moderate mixed climbing toward the top, anywhere from 60 to 80 degrees snow, and AI3 climbing. Then, it was more like M4 and M5 climbing to the top of the snow part. The upper headwall that goes up the direct north face of White Sapphire Peak ended up being a little over 200 vertical meters of climbing and seven or eight pitches of fairly sustained, steep dry tooling. And so there were about two pitches of M7+, a few of M6 and M5, and some alpine ice and snow mixed in.

AAC: How was the quality of the ice and the rock?

CB: It was really good. The rock up there is not granite; it's a gneiss. I studied geology, so I noticed, but you can't tell from far away. It forms cracks differently. It climbed quite a bit differently, but the rock was very solid. Except for one pitch, all the rock was pretty good.

AAC: Can you walk me through from when you left advanced base camp on October 5 until you returned on October 7?

CB: Yeah, so I might back up a bit because we had two attempts on the peak, the first one thwarted by a broken stove when we were 100 meters from the summit. It adds to the lore of the story. The moral of the story is the fuel mix in India is a little different, so it didn't work well with our stove and caused it to overheat. We learned a hard lesson about not taking a backup stove. That was our first attempt, but I'll fast-forward to the successful second attempt.

Starting to rappel from the notch after first attempt. Photo by Vitaliy Musiyenko.

We came down on that first attempt and had a few days at base camp. The weather looked like it would be good again, so we packed our food and some stoves and hiked up there. We waited about six days of weather for a good window to appear at our high camp. We left around three or four in the morning on October 5 from our advanced base camp at 15,800 feet. Then, we had a two- or three-hour glacier approach to the base. After that, we started simul-climbing the lower, less steep section of steep ice and snow. We did about a 1,300-foot simul-climb pitch. Vitaliy led that, and then Hayden led the second half of the ice and mixed climbing to the notch that day. We camped there that evening in our little corner bivy.

The following day, October 6, we woke up and took our altitude med concoction that gave us superpowers. What we had initially climbed as four pitches of steep mixed climbing the first time—we aided a lot of that and left in some of the crucial pins—this time, I suggested we climb it free. We ended up free climbing all of that terrain and didn't aid climbing anything. We did it in two 50-meter pitches. And that got us to our high point. From there, we continued to the summit. There was no terrain harder than those first two pitches. The headwall pops out directly on the small summit. We ended up being on the summit around 7:45 p.m. It was dark by that time of year, so we spent about an hour up there, melted some water, took photos, and enjoyed our time. Then we rappelled in the dark back to our bivy. The next day, we had a slow morning and rappelled back down to our base camp. It was an uneventful third day, which was nice.

AAC: What do you think was your biggest emotional hurdle on the trip?

CB: Oh, man, there were a few of them. A big one for all three of us was definitely the stove breaking on our first attempt. At that point, we were only ten days into our 26-day expedition and were 100 meters from the top. We thought it would be unbelievable if we did this first try. That would leave us with two weeks to climb whatever else we wanted. Accepting the reality that it was unsafe to go up without water was hard for us. We had less than a liter of water to share between three people, which would have been our ration for the whole day. Especially knowing now what the upper terrain is like, I'm super glad we didn’t go that first time. The climbing was still hard and would have taken a long time. Being dehydrated up there is not a safe thing that any of us would be willing to do. So that was a hard truth to accept.

Excited to be at notch bivy before sunset! Photo by Christian Black.

Luckily, the saving grace is that Hayden, Vitaliy, and I are all close friends. Vitaliy and Hayden didn't know each other before the trip, but I'm close friends with both of them. We all have very similar approaches to safety-related decisions. We were all on the same page about flexing the bail muscle. Other than that, we each had our moments of need, which the other two were naturally able to step in and take care of, which was nice.

AAC: How did you end up picking your team?

CB: Hayden is one of my best friends. We worked on the Yosemite SAR team together for a few years. I met him there, and we climbed El Capitan several times together. We just got along energy-wise. Over the past couple of years, we've gotten to go on multiple, more extensive trips together. One of those trips was to Mt. Bute on the Live Your Dream grant. This summer, we went to the Cirque of the Unclimbables for a month. If you're going to be in gnarly places, you want to be with good people. I only climb with my friends in those scenarios—honestly, in most scenarios.

Vitaliy, I met through messaging online. When I worked in Kings Canyon as a park ranger, he had put up a bunch of routes in the Sierra that I kept seeing his name on and was interested in doing. I messaged him to gather information. We ended up linking up on a climb the following year. We had an epic time. We did The Nose in a day as our first climb, and he took a 100-foot whipper. It was really scary, but we both reacted in a way that felt right. It built a lot of trust between us. Even though we haven't always lived in the same place, we'd casually link up for outings. We know each other as solid partners who know their stuff and are easy to get along with.

Photo by Christian Black.

AAC: That's great it worked out so well. It sounds like you had a good team.

CB: Yeah, that was the best part, for sure. You can't compare any experience to doing this with your two best friends. It's just so fun!

AAC: Do you have any fun anecdotes or funny moments from the trip?

CB: The funniest moments were just like how horrible we felt at various times. That is how we each process hard experiences in the moment. You can't help but laugh at it. And that's why we like each other as climbing partners, because none of us take it seriously.

A funny moment for me was when we made it to the bivy notch on the first attempt. It was pretty late, and I had fallen asleep multiple times on the last two pitches. We got up there, and I was boiling the water. It was dark, I was in every puffy layer I owned, and I was ten times more tired than I'd ever been in my whole life at 19,000 feet. I'm holding the Jetboil upright, and my purpose in life has never been more apparent. I hold the Jetboil. If the Jetboil isn't held, the water spills, and we don't drink water. I had an internal moment of reflection, like, wow, life has never been simpler than it is right now. There are only so many times when your life boils down to doing an incredibly simple task. For 45 minutes, that was my whole life.

The first mixed pitch out of the notch bivy. I'm [Christian Black] contemplating how to navigate the unprotected slab to gain the cracks. Photo by Vitaliy Musiyenko.

AAC: Is there anything else you want to add about the trip?

CB: The only thing I have to add is I feel so appreciative of a good team and good friends to be out there with and make hard decisions with. That was our biggest takeaway. We had a two-part goal going into the trip: A) we obviously wanted to come back alive, and B) become better friends. We achieved those goals through the roof. We have a lot of trust in each other. It's a cool medium to experience friendship in.

*Christian Black is writing a feature article for the 2024 American Alpine Journal about this expedition.

The Cutting Edge Grant is Powered By:

The Prescription—December 2023

This month we have an unfortunate accident that occurred several months ago on a popular one-pitch sport route at Sand Rock, Alabama. This accident underscores the sometimes perilous learning curve faced by those transitioning from indoor to outdoor climbing.

Andrea Bender climbing Misty (5.10b/c), the scene of a fatal fall in October 2023. Mountain Project reports that this climb is “not to be missed.” Photo: Andrea Bender Collection

Fatal Fall From Anchor | Inexperience, Inadequate Supervision

Alabama, Sand Rock, Sun Wall

On October 14, Yutung “Faye” Zhang (18) fell 90 feet from the anchors of Misty (5.10b/c) while cleaning this route at Sand Rock in northeastern Alabama. It was her second time climbing outdoors. At around 12 p.m., Zhang, a new climber and part of a larger group, took a final top-rope lap on the route. She cleaned the quickdraws and reached the two-bolt anchor. The anchor was equipped with two mussy hooks plus a single locking carabiner that had been placed by one of the other climbers to guard against the rope from unclipping from the mussys.

No one was at the anchors with Zhang to see exactly what happened. Jun C., who was belaying Zhang at the time of the accident, wrote on Mountain Project, “We put the locker in on the incredibly unlikely premise that the mussys could come unclipped. Not that any of us really thought that would happen, but we wanted to keep our party safe. [While Zhang was on the ground], we communicated and demonstrated what she was to do when she got to the top.... She was aware and confident of just needing to remove a locker and leave the mussys clipped.”

The anchor at the top of Misty. Karsten Delap, a guide who visited the area after the accident, said, “When she undid the (locking) carabiner, she was probably a little bit above [the mussys], with a little bit of slack.” Photo by Karsten Delap

It is assumed that after removing the locking carabiner at the belay, Zhang somehow unclipped the rope from the mussy hooks. Jun C., the belayer, wrote, “Suddenly the rope became unweighted and she (Zhang) wasn’t clipped through the mussys anymore. I fell and smacked my back and head against another rock, and she fell right beside me…. A few of us trained in emergency first response came to aid immediately, as well as a physician that just happened to be in the area. EMS response was quite fast as well, but there was really nothing to be done.”

Jun C. added, “Between all of us we have decades of climbing experience. In our eyes, this [lowering from the mussys] was routine and one of the safest things we could ask of a relatively new climber.” The belayer added, “At the same time, I know all of us are kicking ourselves for asking her to do anything at all.… We’ve all been thinking about what we could or should have done differently or how this could have been a safer experience.” (Sources: mountainproject.com, climbing.com, and the Editors.)

ANALYSIS

A few weeks after the accident, IFMGA guide Karsten Delap climbed this route and provided ANAC with some images and video. He observed that the best handholds at the end of Misty were located above the bolts. (See the video below.) This may have positioned Zhang above the mussys. Then, as Zhang weighted the rope, it might have loaded the mussys incorrectly and become unclipped.

A more in-depth article on best practices for using mussy hooks, written by Delap, will appear in the 2024 ANAC. For now, he writes that, “It is plausible that the rope was threaded from right to left on the mussy hooks, with the locking carabiner positioned between the two hooks. As the climber approached the anchor from the right side, an attempt to remove the locking carabiner involved pulling up above the mussy hooks to introduce slight slack into the system. While this facilitated the removal of the carabiner, it also inadvertently positioned the rope over the gates of the mussy hooks. The belayer, responding to the climber's movement, probably took up slack, felt the climber's weight, and subsequently the gates of the mussy hooks back-clipped under the full force of the climber's weight. This resulted in the rope becoming dislodged from the anchor.”

BE A PRO, KEEP IT LOW

Delap noted that the addition of a locking carabiner to a mussy hook belay was inappropriate for the system. In this case, the locker probably brought the rope above the plane of the hooks, a mistake when considering the “open” nature of mussy hooks.

After the accident, Delap posted an Instagram video detailing some best practices for mussy use. Click here or on the photo to see the video.

“The best thing you can do is always stay below the mussy hooks, both with your anchor setup and your body,” Delap writes. “So be a pro, keep it low.”

Greg Barnes is executive director of the American Safe Climbing Association (ASCA). Though Barnes is a proponent of lower-offs such as mussy hooks, he says these useful tools have inherent limits.

He wrote to ANAC: “Lower-offs include hooks, ram's horns, fixed carabiners, etc. We have had a policy of avoiding hooks for popular top-rope-accessible routes because of the chance of hooks becoming unclipped as someone transitions to rappel.”

Although mussys have a proven safety record, Barnes believes, they still require eduation. He writes, “In Owens River Gorge, lower-offs [have been] the standard since the early ’90s. Despite very heavy climber traffic for 30 years, there have been very few anchor changeover accidents compared to similar areas with closed anchors. In the Sand Rock case, we don’t know whether the rope became accidentally unclipped or if the climber unclipped them on purpose. It is wise to have direct supervision—namely an experienced climber at the same anchor—when a new climber cleans an anchor.” (Sources: Karsten Delap, Greg Barnes, and the Editors.)

Sign Up for AAC Emails

EDUCATE: Everything You Didn't Know About Royal Robbins

Most climbers know the name Royal Robbins. But how much do you really know about this legendary figure in American climbing? Writer and editor David Smart has written a new award winning biography of Royal, called Royal Robbins: The American Climber. The AAC sat down with David to discuss how Royal’s revolutionary years in Yosemite fits into the grander scheme of climbing history, the undervalued climbs from Royal’s life, his writerly intellectualism, bringing nuts to the US to replace pitons, his famed frenemy Warren Harding, and his mixed feelings around bolting throughout his career. Dive into the episode to learn more about one of climbing history’s biggest personalities!

The Line — November 2023

Fresh new stories from the American Alpine Journal.

Above: The 19-pitch route called The Ritual of Hardship on Anafi in the Cyclades Islands. Photo by Kyriakos Rossidis. Below: Rossidis climbing the crux pitch (5.12b) of The Ritual of Hardship. Photo by Jenny Schauroth.

A BIG WALL ABOVE THE AEGEAN SEA

The stunning photo above shows the nearly 500-meter southeast face of Mt. Kalamos on the Greek island of Anafi. The route is The Ritual of Hardship, and it climbs 19 pitches straight out of the sea. Completed in May by an international crew, the route goes all free at 7b (5.12b) or at 6c+ (5.11c) with a smattering of easy aid; a full rack is required to supplement the bolts on the climb. Two earlier routes climbed the buttresses partially in view at far left, but this was the first ascent of the proud southeast face. The full report by Kyriakos Rossidis from Cyprus, along with a pitch-by-pitch route description, are available now at the AAJ website.

HIDDEN MOUNTAINS OF CENTRAL ASIA

The western side of unclimbed Pik 5,253m. Photo by Paul Knott.

The Western Kokshaal-too mountains of southern Kyrgyzstan are among the most beautiful peaks of Central Asia, and it’s an open secret that some of the most enticing faces in this range are just over the border in China. (The incredible and often-attempted southeast face of 5,842-meter Kyzyl Asker, for one.) This summer, Paul Knott and Sam Spector took a peek over Kotur Pass at the unclimbed faces above the Rudnev Glacier basin, finding yet more ice-draped granite on alpine faces 600 to 700 meters high. See Knott’s enticing report and photos at the AAJ website.

JP Preuss carefully traversing into the Right Leg Couloir during the first ski descent of Mt. Breitenbach’s north face. Photo by Marc Hanselman

WILD SKI DESCENT IN IDAHO

Idaho guide Marc Hanselman, along with Paddy McIlvoy, put up the only new route on the north face of Mt. Breitenbach in the past two decades: Cowboy Poetry, climbed in 2019. That ascent and other exploration convinced Hanselman that a ski descent of the very steep face might be possible in just the right conditions. Late in April, the stars aligned and Hanselman and Jon “JP” Preuss managed the first descent of Breitenbach’s imposing face, a 2,500-vertical-foot line that took an hour and a half to piece together, with no rappels or belays. Read all about it at our website.

HARDEST FREE ROUTE IN THE HIGH SIERRA?

In September, Connor Herson and Fan Yang free climbed Hairline on the east face of Mt. Whitney, the highest peak in the Lower 48. Hairline is a very steep, 13-pitch route originally climbed in 1987. The 55-meter crux pitch went at 5.13+ (8b), at over 13,000 feet in elevation; two other hard pitches go at 5.12 and 5.13-. Hairline is now probably the most difficult free climb in the High Sierra. Connor and Fan, who had never climbed together before their climb on Mt. Whitney, talked about their impromptu long-weekend mission to free Hairline for the latest Cutting Edge podcast.

TOOLS FOR THE WILD VERTICAL

Wondering what to get the climbing history buff in your life for the holidays? John Middendorf’s Mechanical Advantage: Tools for the Wild Vertical is a passionately researched and heavily illustrated history of early gear for climbing and alpinism. One sample of Middendorf’s work appeared in AAJ 2022, for which he wrote the fascinating biography of Tito Piaz, the ground-breaking Italian climber of the early 20th century—just a smattering of the fascinating material he has uncovered. The two-volume Mechanical Advantate is available in several print and digital formats.

The Line is the newsletter of the American Alpine Journal (AAJ), emailed to more than 80,000 climbers each month. Find the archive of past editions here. Interested in supporting this online publication? Contact Billy Dixon for opportunities. Questions or suggestions? Email us: [email protected].

Sign Up for AAC Emails

CONNECT: Behind the Scenes of Climbing Mentorship, with Kimber Cross and Kit DesLauriers

Kimber in action. Photo Courtesy of Kimber Cross.

Showing off her custom prosthetic ice tool. Photo courtesy of Kimber Cross.

Kimber Cross is an adaptive climber who uses a custom prosthetic ice tool to climb waterfall ice around the country as well as alpine ice routes in her home state of Washington. She is a part of The North Face’s Athlete Development Program, and her mentor is long-time AAC supporter Kit DesLauriers, the first person to ski the seven summits. The AAC sat down with Kimber and Kit to talk about Kimber’s emerging career in alpinism and ski mountaineering. We also cover mentorship, setting goals, and some of the ways the larger climbing community makes assumptions about adaptive climbers. Dive in to hear some fascinating tales from the mountains—including raising a wolf and doing a bit of spontaneous hangliding in the Tetons—and to learn more about how Kimber is pushing her climbing and changing the narrative.

Four New Routes on Baffin Island, Canada

Noah Besen Climbing. Photo by James Klemmensen.

A Story from the 2023 Cutting Edge Grant

By: Sierra McGivney

Noah Besen didn't expect to find the Atlantic Ocean frozen in the middle of July outside of Qikiqtarjuaq, a hamlet on Broughton Island, in the Nunavut territory of Canada, off the coast of Baffin Island.

Billy Arnaquq, a local outfitter and guide, remarked, that there was a lot more sea ice than normal for this time of year. The plan had been to kayak to Coronation Glacier, about 75 or 80 kilometers from town, and then hike up and into the glacier. From there, they would attempt to ascend granite walls accessible from the glacier. Besen and the rest of the team, James Klemmensen, Shira Biner, and Amanda Bischke, wanted the expedition to be as human-powered as possible, but there were apparent limitations. They couldn't unfreeze the ocean…And they had about 1,000 pounds of gear.

About 20 kilometers south of town, the ice was beginning to break up, so the trip was still very much within reach. Arnaquq snowmobiled them out with a big load of their gear to the southern limit, where they stashed their equipment on a little island. They wanted to start the expedition with a human-powered effort, even if it meant changing their original plan. He snowmobiled them back, and they began their journey, walking across the sun-pocketed ice with day packs back to their stashed gear, seals and icebergs lining the way.

“That was the first big crux,” said Besen.

Noah Besen in the front and Shira Biner in the back of the boat. Photos by James Klemmensen.

Once on the island, they decided to wait out the ice breakup, thinking it would only take a couple of days. A week passed, so they took matters into their own hands and planned a “staged gear shuttle.” The 24-hour sun poured over them as they dragged their gear to the ice's edge. Dry suits on and boats packed, they individually heaved their boats until the ice cracked and they plopped in. Four days later, they saw the Coronation Glacier flowing into the ocean.

Ten kilometers up the Coronation Glacier, they made their basecamp, where the glacier splits into two forks, surrounded by huge rock cliffs. They would stay on the glacier for 20 days. Now, the climbing would begin.

The team spent days on the glacier with binoculars in hand, scouting out different possible rock climbs and sometimes hiking for hours to get a better angle on certain features. Klemmensen and Besen found a route near their base camp and “just went for it.”

“We brought enough stuff that we're like—if it doesn't make sense, we have what we need to … just epic back down,” said Besen.

Twenty hours of climbing on multicolored alpine granite later, the two put up a new route, Salami Exchange Commission (800m, V 5.10). They slept on the top of the wall and spent the next day returning to base camp.

Photo by James Klemmensen.

Blank chossy walls near camp stymied Bischke and Biner, so they decided to venture to another section of the glacier. Four thousand-foot walls loomed over them as they searched for a choss-free wall to climb. A lower feature snagged their attention. Psyched, they put up a new route, The Big G (350m, III 5.8 ).

Storm clouds gathered, and rain descended on the team, staying for a week. The days drizzled by. Once the week was up, the rain cleared, and the walls dried. Besen and Klemmensen started another epic.

From far away, Escape from Azkaban looked heinous; blocky rocks and blank faces seemed to greet the two, but once up closer, perfect splitter cracks formed the route. The route was 650 meters and had the most challenging climbing on the trip, with the grade of IV 5.10+.

“It proved to be the best alpine rock I've ever climbed in my whole life,” said Besen.

The journey back was the inspiration for the name. After topping out, they descended an easier-looking route involving some scrambling. They popped out on a side glacier that connected to the main Coronation Glacier that their base camp was on. Glaciers are constantly moving, creating, and ever-changing. This side glacier had carved out a canyon with raging river rapids, between 60 and 70 feet deep, completely impassable.

At three in the morning, the two ate the last food, mulling over their unfortunate circumstances. The sun hovered on the horizon—all hours normally considered night appearing like sunset—allowing endless daylight hours for their epics. They journeyed around the river and onto a boulder field with water running underneath it.

“The name came from us feeling trapped and needing to escape,” said Besen.

Photo by James Klemmensen.

Bischke, Biner and Besen attempted another route, but unfortunately, had to bail. The rock had become very loose, so they decided to put in a couple of bolts and abandon the project. After returning, both groups finished the trip together on one last attempt.

Cerulean water pooled on the sides of the glacier, forming deep, bottomless basins in between the bedrock and the glacier. Besen, Bischke, Biner, and Klemmensen stared down at the water, the rock on the other side just out of reach, but they started to get to work. Besen had brought his dry suit on the glacier in case they might have to ford a raging river. They constructed an anchor using ice screws and lowered Besen into the water.

“I didn't have to swim that much. I got into about my chest, and I was able to lean, reach, and scurry up,” said Besen.