by Allison Albright

“It had all begun on an afternoon some nine months previous. Four of us were lying about relaxing after a particularly fine Teton climb when someone enthusiastically suggested, “Let’s climb the south face of McKinley next summer!” To attempt a new and difficult route on North America’s highest mountain seemed a most worthwhile enterprise; without further ado, we cemented the proposal with a great and ceremonious toast.”

The standard route up Denali is via the West Buttress, first ascended by Bradford Washburn in 1951. The West Rib was as yet unclimbed and promised to be a more technical climb than the West Buttress route.

In June of 1959 the expedition team arrived in Alaska and reached the foot of Denali by plane. The team was led by Jake Breitenbach and composed of three others: Barry Corbet, Pete Sinclair and William Buckingham. The average age of the expedition members was just 23-years-old, making it one of the youngest expeditions to attempt such a climb at that time.

“Towards evening the clouds, which had been hanging low all day, began to rise, revealing a magnificent view of the brutal immensity of Mount McKinley’s south face. Our proposed route, the rib at the western edge of the face, was graphically laid out before us: first, a great rock buttress rising abruptly out of the glacier; above, an apparently gentle but heavily corniced snow ridge; and then, sweeping steeply upwards again, the final 5000-foot upper face consisting of numerous shallow snow gullies and narrow ridges of bare rock.””

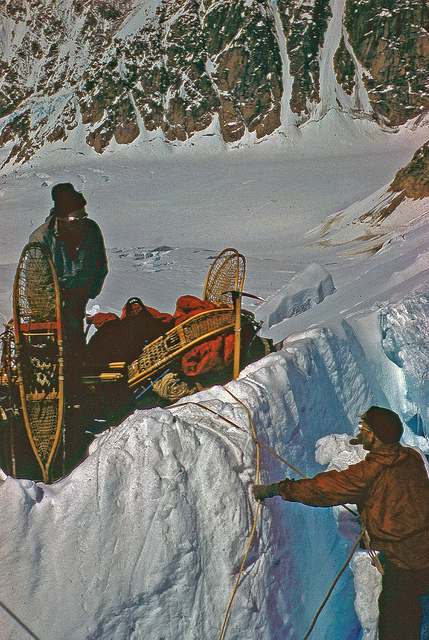

Day two was spent relaying loads of supplies to Base Camp, situated near the icefall at about 9600 feet. That night, a great deal of food and about 1700 feet of rope were airdropped in, landing a few yards away from the tents. Day three saw Barry and William trying to find a way through the icefall.

“The lower section, a great bulging slope, offered no serious difficulties. Above, an uncrevassed peninsula led onwards between areas of huge tumbled blocks and wildly contorted crevasses, finally ending abruptly at a deep crevasse or chasm separating us from a large, semi-detached sérac from which a route might possibly continue. Furthermore, it was entirely obvious that there existed no other route into the upper basin, so we had to somehow get across to the sérac.”

They noticed that a thin blade of ice descending about 15 feet on the near side of the crevasse, coming close to the far side. Barry and William changed their snowshoes for crampons and made their way across the icefall to the North side of the glacier, where they set up camp at a small bergschrund at the base of a rock buttress. They named it Icefall Camp and returned to Base Camp for the night, to set out for Icefall Camp with more supplies and the rest of the team the next day.

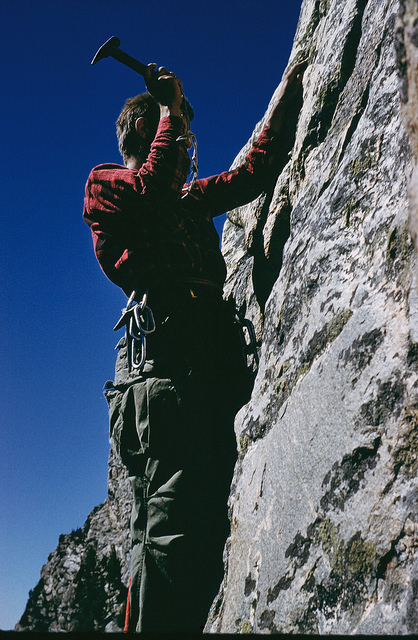

The next morning, after bringing more gear to Icefall Camp and pausing for lunch, Jake and Pete went to scout a route up the buttress. They found that the route up that way was blocked by a gendarme (a rock pinnacle blocking access to an areté) and the only possible route remaining was a traverse to the east into a steep snow gully.

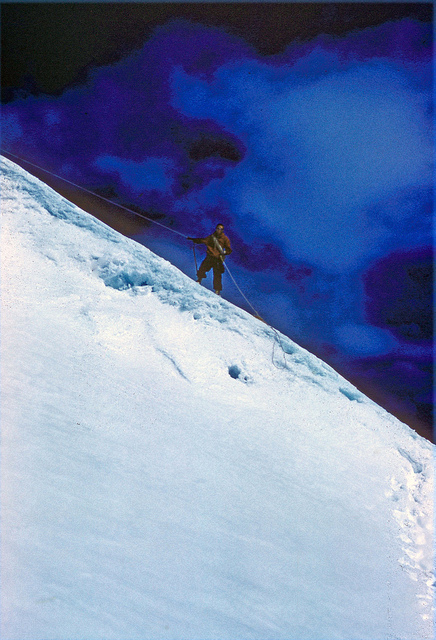

The gully turned out to be mostly ice, covered by a half inch of snow. After several hours of chipping steps into the ice and placing about 800 feet of fixed rope, the group was still only about halfway up the gully. The following day was spent relaying loads of supplies to the base of the gully and beginning the route up the fixed ropes with gear.

“The warm morning sun had transformed the center of the gully into a continual avalanche of slush, and rocks frequently plummeted down beside us, but we were relatively safe on the edge of the gully, although once a large rock, ricocheting from side to side, very nearly wiped out the entire expedition, one by one.”

It took placing an additional 800 feet of fixed rope before they arrived at the tip of the gully, the crest of the buttress. After relaying supplies to the top, they were able to chop a platform in the ice barely big enough for a tent.

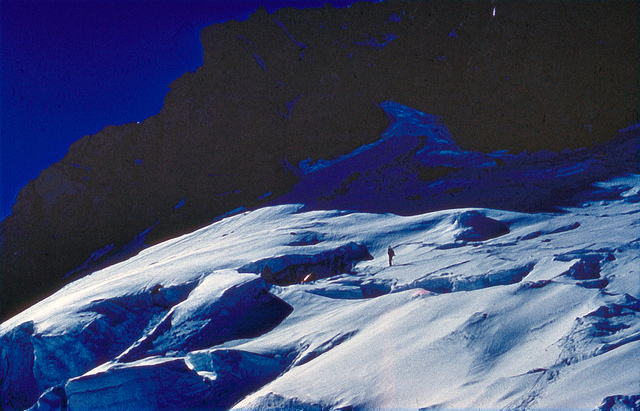

In the morning, the team found that the ridge above rose in two great white domes or bumps before leveling off onto a narrow plateau. The only possible route was a direct ascent of the second of the bumps, which was steep and glassy ice. To ascend this way, they would have to retrieve some of the fixed rope they’d placed in the gully and place it along nearly the entire route up the ice bump. The two bumps ended up requiring a total of 1700 feet of fixed rope to make it possible to ascend.

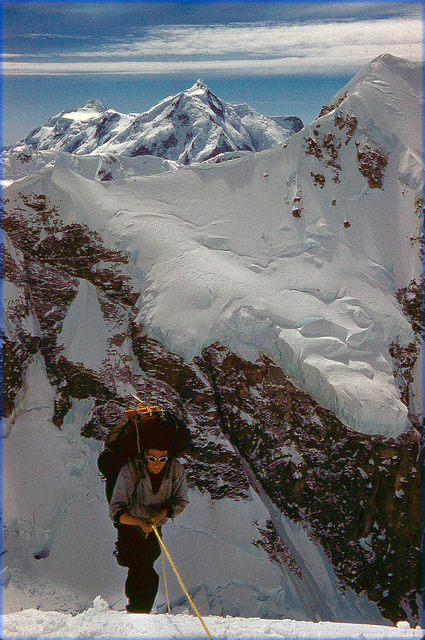

At the top of the bumps was a broad ridge that was nearly level for most of its length until it gradually became a steeper rock face. They set up a luxurious 2-tent camp at the base of that steeper portion at 13,900 feet and named it Camp Paradise.

By June 16th they’d made their way to 14,800 feet. Though the route was somewhat less difficult, the altitude had an effect and their camp for that night was dubbed Camp Fatigue. The following morning brought a change in the weather and the team knew they’d only get a few more days of decent weather to work with. The plan was to split the gear into eight loads and make two treks up the areté to the West Buttress where they would see if it was possible to traverse. They would leave the first loads there, return for the second half and then make a stripped down camp as high as possible in order to attempt a summit assault on the 19th.

All went according to plan the next day and by late afternoon the team had reached the base of a 250 foot rock bastion at about 16,500 feet. There they camped on a “little jutting promontory of rock” which only required a little remodeling to make it possible to pitch a tent. This they named Balcony Camp.

After rising early, the team made their way up the first steep walls to about 18,000 feet, where they found they were on a wide and shallow couloir which rose steeply upwards.

“As we climbed higher, the angle began gradually to decrease, and, stepping around a corner, we suddenly emerged onto the western edge of the great snow plateau which stretches from the top of the South Peak to the Archdeacon’s Tower. The long walk across the level 19,500-foot plateau and up the final snow face seemed interminable, but we all eventually reached the summit between four and five in the afternoon. The sky above was brilliant and clear and scarcely a breath of wind stirred. But below, the clouds had once more moved in and almost totally obscured the view, increasing the sensation of height and remoteness. Our emotions were a mixture of intense satisfaction and slight disbelief as we relaxed briefly on the summit. But the hour was late and the distance yet far to go, so we regretfully turned our steps downward. When, half exhausted, we got back to Balcony Camp at about 10:30 p.m., snow was falling gently.”

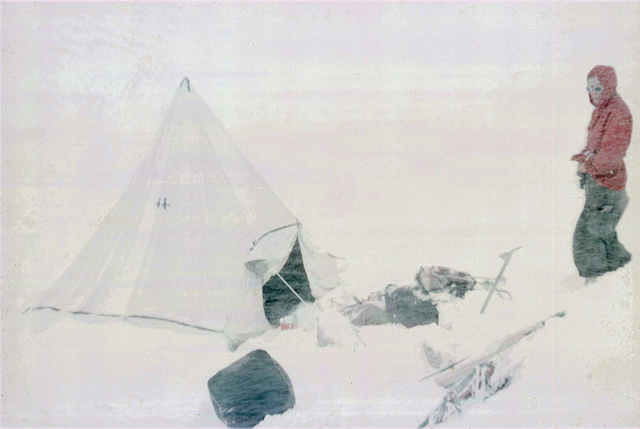

When they woke on the morning of June 20th, nearly 2 feet of fresh snow had accumulated at Balcony Camp and it was still falling. The team took the hint and began their descent. The accumulation of snow had changed the landscape and obscured landmarks, causing an anxious time trying to find caches of supplies and food they’d left for themselves on the way down. While visibility was low because of the storm, they were able to make their way down the West face without falling into a crevasse. Before long they’d joined up with the West Buttress Route and reached Windy Corner at 13,200 feet with only one minor crevasse-related incident. They camped for the night at Windy Corner and in the morning aimed themselves downward in whiteout conditions.

“A few miles below Kahiltna Pass we suddenly found ourselves hopelessly floundering in armpit-deep snow. There was nothing to do but set up a temporary camp and wait for the snow to freeze. Three days and many snowstorms later, we were still sitting idly in the same miserable spot, which came to be known as Frustration Camp. Finally, after midnight on the fourth day, we found the skies clear and the crust firm. We rapidly threw our packs together and set off down glacier to the place where Sheldon was to pick us up in a small cove below the northeast face of Mount Crosson. ”

They spent the next few days camped there until, on June 27th, they could hear the unmistakable sound of an approaching airplane. Sheldon had arrived to collect them and their new route was a success!

For this post we used William Buckimgham’s American Alpine Journal report pretty heavily. It’s a great first-hand account and a fun read. You can find it here.

The photos included in this post are from the library’s Barry Corbet Collection. Check out more on Flickr.

To read more about Denali, the library recommends:

Denali’s Howl by Andy Hall

In the Shadow of Denali by Jonathan Waterman

Mount McKinley: the conquest of Denali with text by Bradford Washburn and David Roberts and photos by Bradford Washburn

A Tourist Guide to Mount McKinley by Bradford Washburn

Mount McKinley's West Buttress: the first ascent by Bradford Washburn