David Hauthon on Directissima (5.9), The Trapps, Shawangunks, New York. Land of the Mohican and Munsee Lenape people. Photo by AAC member Francois Lebeau.

Setting the Standard

By the Editors

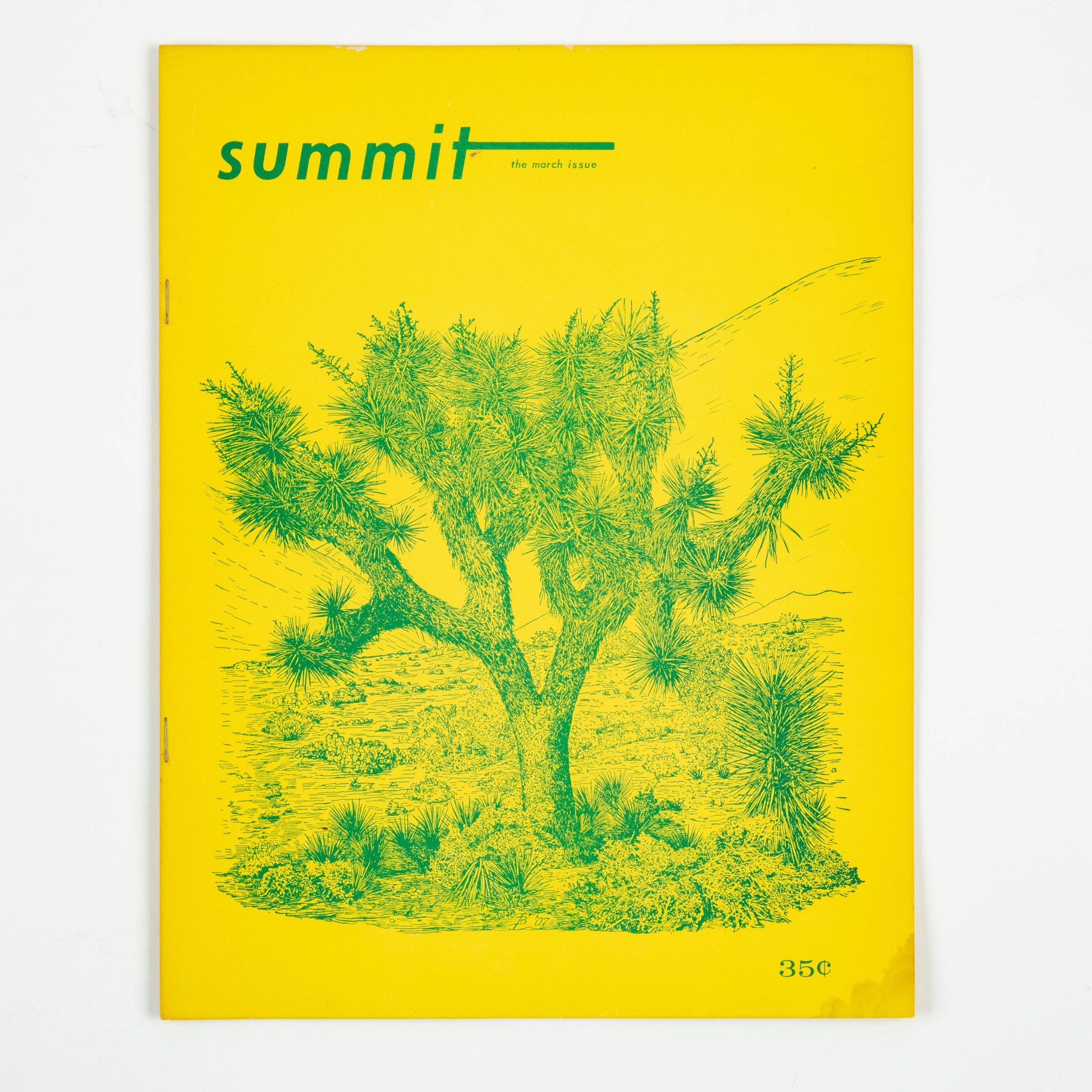

Before there were 8a.nu leaderboards and Mountain Project ticklists, before there were beta videos and newspaper articles for every cutting-edge ascent, there was a word-of-mouth understanding of who was setting the standard of the day.

Pushing the standard of climbing at the Gunks has proven to be key in the history of climbing in the United States, and any connoisseur of climbing history will know the names of Fritz Wiessner, Hans Kraus, Jim McCarthy, John Stannard, Steve Wunsch, and John Bragg—all AAC members by the way. But what often gets overlooked in the whispers of rowdy Vulgarian parties, naked climbing antics, and strict leader qualifications that swirl around Gunks history are the distinct contributions of women to Gunks climbing. A central figure in this story is the unique character Bonnie Prudden.

First, we must set the scene. Prudden was most active climbing in the Gunks in the late 1940s and early 1950s, when climbing on rock was done in sneakers with a hemp rope. Rather than boldness, a strict no-falls attitude pre-vailed, and good judgment was prized over achieving the next cutting-edge grade. Pitons and aid climbing were status quo, and without a priority on pushing the limits of the sport, the time period was considered non-competitive. While Wiessner, Kraus, Prudden, and others were climbing 5.7s (even occasionally 5.8), most climbers stuck to routes rated 5.2–5.4.

Climbing in the Gunks started with Fritz Wiessner, who went on a developing tear starting in 1935. He and Hans Kraus would be the leading developers of the area until the late 1950s, collectively establishing 56 of the 58 multi-pitch climbs put up in that period. In 30 of those first ascents, Prudden played a role, and she wasn’t just tagging along.

With competition on the back burner, the significance of leading was murky. Some of the climbers at the time proclaimed that there wasn’t a big difference between leading and following. However, the great tension and division that would characterize the Gunks’ history— between the Appalachian Mountain Club climbers (Appies) and the rebel Vulgarians that opposed their rules—came down to the question of regulating leading. The Appies, the dominant climbing force in the Gunks until the Vulgarians and other rabble-rousers splintered the scene in the 1960s, created a lead qualification system, determining who could lead at any given level. Alternatively, some climbers were designated as “unlimited leaders,” who didn’t need approval to lead specific routes.

Although they were painted as control freaks by the Vulgarians, the truth behind why the Appie crowd was so invested in regulating leading (and minimizing the risk inherent in climbing) was because they were keenly aware of the generosity of the Smileys, the landowners who looked the other way as climbers galavanted around on the excellent stone of the Trapps and Sky Top.

Bonnie Prudden was lucky enough to rise above all of the drama. As a close friend and frequent climbing partner of Hans Kraus’s (who was obviously an “unlimited leader,” being one of the first, and much-exalted, developers of the area), Prudden had frequent access to new, difficult climbs. In interviews with researcher Laura Waterman, Prudden relayed that in the early years, while climbing with her then husband, Dick Hirschland, she always led because of their significant weight difference. Later she took the lead simply because of her skill, tutored by Kraus and Wiessner.

Shelma Jun on Harvest Moon (5.11a). Photo by AAC member Chris Vultaggio.

Prudden took her first leader fall on the 5.6 Madame G (Madame Grunnebaum’s Wulst) and recalls catching a fall from Kraus only four times. At the time, 5.7 and 5.8 was the very top of the scale, and Prudden was keeping up—and sometimes showing off.

The story of the first ascent of Bonnie’s Roof, now free climbed at 5.9, is often held up as proof of Prudden’s talent, and rightfully so. But the gaps in the story and the fuzziness of Prudden’s memory of it might reveal more than the accomplishment itself.

On that day in 1952, Prudden thought the intimidating roof “looked like the bottom of a boat jutting out from the cliff,” as she wrote in an article about the climb in Alpinist 14, published in 2005.

Overhanging climbing was still a frontier to explore, but Kraus was a man on the hunt for exposure, rather than difficulty. It just so happened that the massive overlapping tiers of Bonnie’s Roof would provide both.

Prudden wrote about the first ascent: “I don’t remember who took what pitch since by then we were swinging leads. But I do remember quite well reaching the Roof’s nose. This airy feature was the reason for the climb. Getting to it had been one thing; getting over it would be something else.” The very fact that she couldn’t remember the precise order of leads indicates how commonplace this was for her—how comfortable she felt on the sharp end.

Kraus struggled for a long time to find a place for a piton over the roof, and ultimately backed down in a huff, ceding the lead to Prudden. As she started up on the sharp end to see if she could locate the next hold that Kraus could not, she quickly found a hole over the lip that would take gear, a massive positive jug that was hard to see from below. She nailed in the piton without weighting it, pulled over the lip with ease, and ultimately climbed the pitch with only one point of aid. It seems that she “floated it,” as we might say today. Rather than the giddy breathlessness one might imagine upon pulling a strenuous lip encounter and succeeding where Kraus could not, Prudden’s first ascent seemed to get a shrug of the shoulders. This was just the usual business, and her telling of it reveals just how blasé climbing at the top of the standard was for Prudden.

Carmen Magee on Tulip, (5.10a). Photo by AAC member Chris Vultaggio.

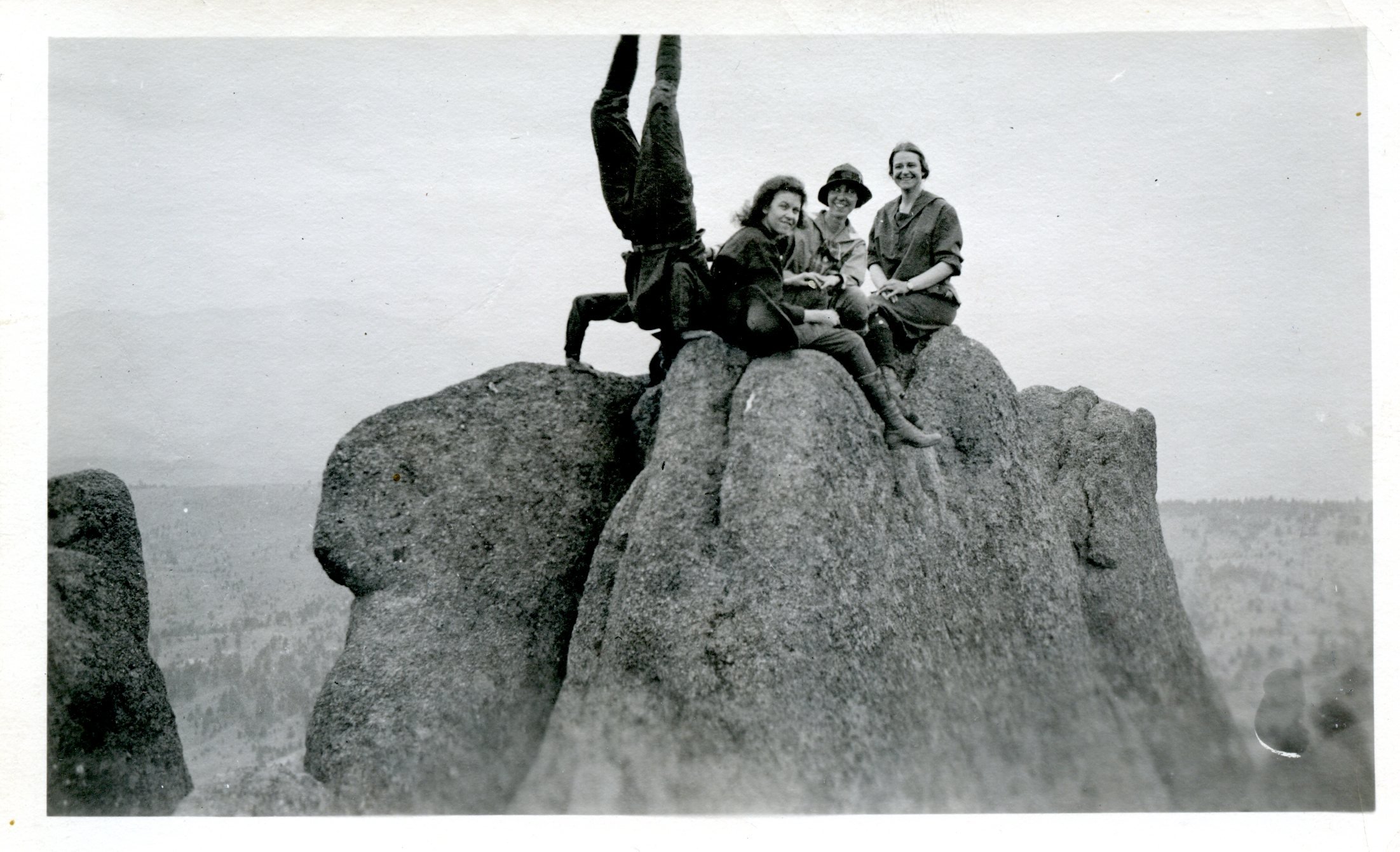

Prudden’s involvement in 30 first ascents, including several at the highest difficulty of the day, had her setting the standard of the time. But researcher and historian Laura Waterman has uncovered a weird quirk to Gunks climbing history that should be noted. Women were involved in over half of the FAs during the 1940s, but decreasingly so in later decades. For example, between 1960 and 1970, only 5% of first ascents involved women.

Indeed, many female climbers of the later decades note a cultural sentiment about the frailty of women regarding sports, as an AAC Legacy Series interview with Elaine Matthews, iconic Vulgarian during the 1960s and 1970s, reveals. According to Matthews and others, there was a perception that women and girls “might hurt their reproductive organs” if they ran or did other forms of athletics. Women would not be climbing at the top of the standard in the Gunks again until the late 1970s.

Funnily enough, though she had an outsized effect on early first ascents of multi-pitch Gunks classics, none of these climbs were included in her climbing résumé when Prudden (then going by her married name, Hirschland) applied for AAC membership. Though she was accepted as the 652nd member of the AAC in 1951 on the merit of the mountains she’d climbed, today her legacy is much more tied to first ascents like Bonnie’s Roof, Something Interesting, Oblique Twique, Hans Puss, and Dry Martini.

For the women who came after her, perhaps the shrug at the Bonnie’s Roof belay is more important than the first ascent.

The Gunks: A Climbing Timeline

The Time of the Appalachian Mountain Club or “Appies”

1935

European Fritz Wiessner discovers the Gunks’ climbing potential and begins opening up new routes in the 5.2–5.5 range.1940

Hans Kraus, another European climber, arrives in the Gunks. By 1950, Kraus and Wiessner would be responsible for putting up 56 of the 58 multi-pitch climbs in the Gunks. Twenty-three of the FAs went to Wiessner, 26 to Kraus, and seven to them both.1941

AAC members Kraus and Wiessner put up High Exposure (5.6), a Gunks classic.1945

The “Appies,” or members of the Appalachian Mountain Club, are regularly climbing at the Gunks on weekends. Due to safety concerns and fears of stepping on the toes of the private landowners, the Smileys, the Appies soon adopt a strict set of regulations, including requiring registration to come on climbing trips, designating rope teams and climbs, and creating restrictions on who is qualified to lead and at what level.

Bootleggers

Early 1950s

The Bootleggers, largely consisting of Kraus’s climbing circle of friends, sidestep the restrictions of the Appies and often climb the hardest routes of the time.1952

AAC member Bonnie Prudden leads the intimidating roof of what would become Bonnie’s Roof, with one point of aid, when her climbing partner, Kraus, can’t figure out the roof move (now climbed at 5.8+ or 5.9).1957

AAC member Jim McCarthy puts up the hardest rock climb in the Northeast with Yellow Belly (5.8 or 5.9), through a steep roof, ushering in a culture of pushing the standard.

The Vulgarians

1957

Art Gran splits with the Appies. The Vulgarians are born when he joins and mentors some college party kids who begin resisting the leader regulations upheld by the Appies.Late 1950s

Rich Goldstone and AAC member Dick Williams establish boulders now graded up to V6 and V7 in the Trapps, though bouldering is mostly considered a training tool at this time.1960

Jim McCarthy introduces the first solid 5.9 at the Gunks with his ascent of MF.

1967

AAC member John Stannard climbs the iconic Foops, ushering in 5.11 using repeated falls and rehearsal tactics.1970

The first Vulgarian Digest is published; “blame” goes to Joe Kelsey.

The Clean Climbing Era Begins

1972

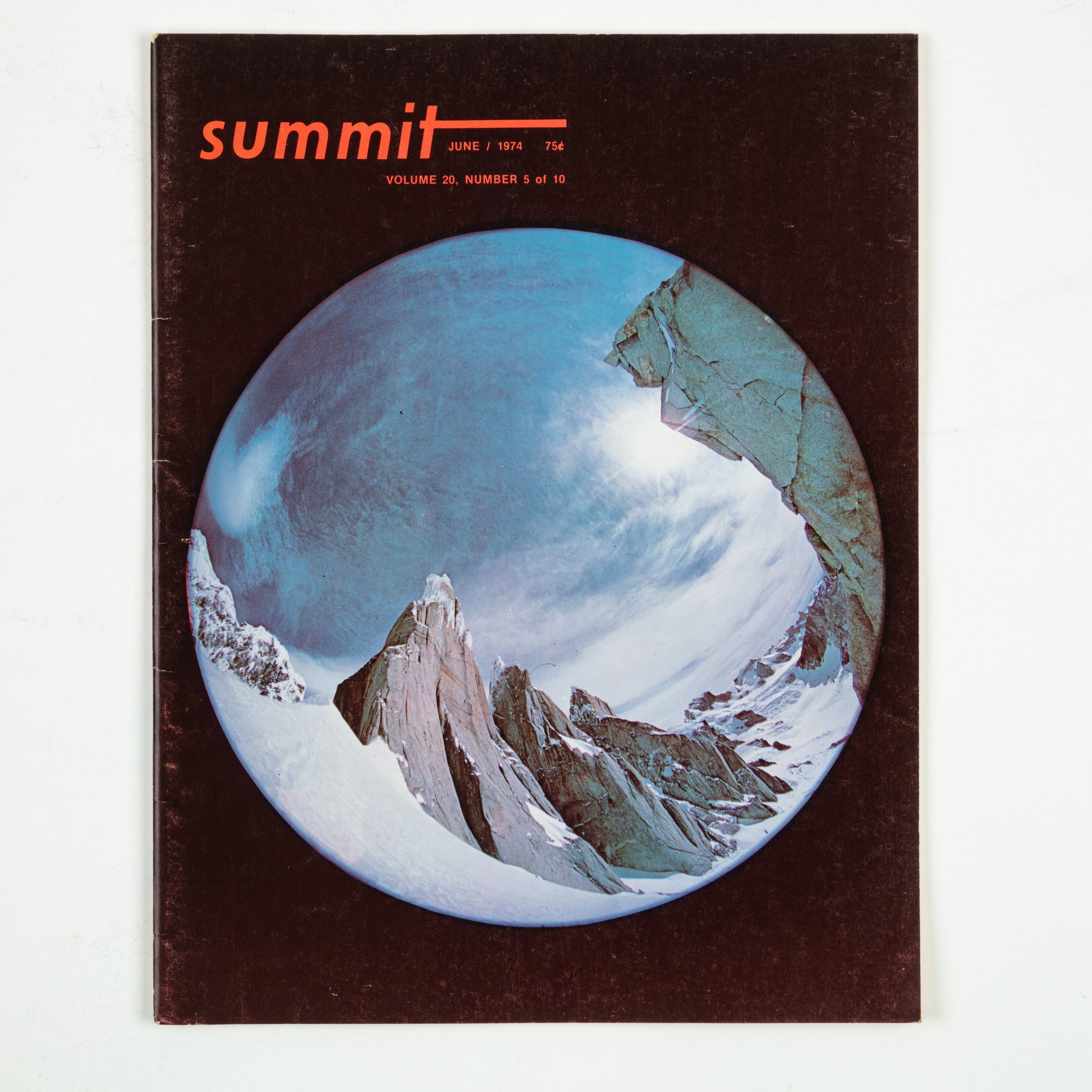

The clean climbing movement, largely spearheaded by John Stannard in the region, overhauls the old ways.1973

Standard and AAC members Steve Wunsch and John Bragg usher in 5.12 while trying to free old aid lines. Of particular note are Kansas City (5.12-) and Open Cockpit (5.11+ PG13).1974

Wunsch frees Supercrack, probably the hardest climb in North America, possibly even the world, at the time.1977

Barbara Devine reestablishes the women’s standard (after an extensive lull), climbing Kansas City and desperate 5.11s like Open Cockpit, To Have or Have Not, and Wasp Stop, among others. In 1983 she does the first female ascent of Supercrack.

The Great Debate on Ethics and Style

1983

AAC member Lynn Hill makes a splash as one of four Gunks climbers to master Vandals, the Gunks’ first 5.13.1986

“The Great Debate” is held at an AAC member meeting, attended by many Gunks legends, fleshing out questions about rap-bolting, hangdogging, and other modern climbing tactics versus the traditional style of ground-up development and ascent.Late 1980s

AAC member Scott Franklin pushes Gunks standards to 5.14 with his ascent of Planet Claire, sometimes considered the world’s first traditional 5.14, despite the few bolts that protect the crux. Franklin also establishes modern testpieces like Survival of the Fittest (5.13a), which he later solos, and Cybernetic Wall (5.13d).

Resurgence of Bouldering

2006

The Mohonk Preserve and the American Alpine Club (alongside the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation and the Palisades Interstate Park Commission) partner to create a campground within walking distance from some of the Gunks’ greatest crags.2023

William Moss establishes a 5.14d R at the Gunks with his first free ascent of Best Things in Life Are Free (BT).2024

Austin Hoyt puts up The Big Bad Wolf, the first V15 in the northeastern United States.

A huge thanks to Laura and Guy Waterman and Michael Wejchert, whose research and book Yankee Rock and Ice is the basis for much of this timeline.

Book Your Stay at the Gunks—AAC Lodging

The AAC’s lodging facilities are a launch pad for adventure and a hub for community. Experience this magical place for yourself by booking your stay at the Samuel F. Pryor III Gateway Campground today.

AAC members enjoy discounts at lodging facilities across the country. Not a member? Join today.