In this episode of the podcast, we are celebrating the recipient of the AAC’s 2025 David Brower Conservation Award: Outdoor Alliance. Outdoor Alliance is the only organization in the U.S. that unites the voices of outdoor enthusiasts to conserve public lands and waters. OA advocates and amplifies the voices of recreationists to help ensure those lands are managed in a way that embraces the human-powered experience. Over the last 10 years, Outdoor Alliance has been instrumental in helping pass the EXPLORE Act in 2024, and they are receiving the Brower award for their work on passing this instrumental recreation bill. Dive in to the episode to hear about the origins of Outdoor Alliance and the power behind their methods and perspectives, featuring Outdoor Alliance CEO Adam Cramer, and the AAC’s Policy Director Byron Harvison.

The Prescription—Fall on Rock

This July, we look back at an accident in 2019. A climber took a serious lead fall while clipping the third bolt on a popular sport route in North Carolina called Chicken Bone (5.8). This climber made a fairly common error when his rope crossed behind his leg while climbing. This oversight resulted in serious injury from what should have been a routine fall.

Easy access and solid quartzite make North Carolina’s Pilot Mountain a popular destination. Photo: bobistraveling

FALL ON ROCK | Rope Behind Leg, No Helmet

North Carolina, Pilot Mountain State Park, The Parking Lot

According to Mountain Project, Chicken Bone is an “awesome moderate and one of the longest routes at Pilot [Mountain].” The route has also seen several accidents in the last decade, including two serious falls at the third bolt (yellow circle). Ben Alexander

During the afternoon of May 6, Ranger J. Anderson received a call reporting a fallen climber. When Anderson found the patient, Matthew Starkey, he was walking out, holding a shirt on the right side of his head and covered in blood. However, he was conscious and alert. After ensuring the patient’s condition did not worsen, Anderson accompanied him on the hike. Medical assessment revealed a two-to three-inch laceration on the right side of his skull and light rope burns on his leg.

Starkey explained to rescuers that he had been lead climbing outdoors for his first time on the route Chicken Bone (5.8 sport). As he was nearing the third bolt, he lost his grip on a hold and fell. His rope was behind his leg, and this caused him to flip upside down and hit his head on a ledge below. Starkey said he was unsure, but felt like he had “blacked out.” He was not wearing a helmet.

(Source: Incident Report from Pilot Mountain State Park.)

Video Analysis—Rope Behind Leg

Many of us have fallen and had the rope catch behind our leg. Usually, we get nothing more than a bad rope burn. Unfortunately, there can be severe consequences if we get a hard catch, flip upside down, and strike our head.

Pete Takeda, Editor of Accidents in North American Climbing, is back with some advice on how to fall correctly.

Pete Takeda, Editor of Accidents in North American Climbing; Katie Ferguson, Executive Assistant; Producers: Shane Johnson and Sierra McGivney; Videographer: Foster Denney; Editor: Sierra McGivney. Location: Canal Zone, Clear Creek Canyon, CO.

ANALYSIS

Avoid getting your feet and legs between the rock and the rope. A fall in this position may result in the leg snagging the rope and flipping the climber upside down.

While many sport leaders pass on wearing a helmet, this accident is a good example of its usefulness. Leading easier climbs can increase the risk for injury, as they often tend to be lower angle and/or have ledges that a falling climber could hit. (Source: The Editors.)

Editor’s Note: This was Starkey’s first outdoor climbing lead, and his lack of experience perhaps contributed to the accident.

Chicken Bone has been the scene of multiple accidents, mostly involving inexperienced climbers. Here are two more examples:

2021 | Fatal Fall From Anchor — Inexperience at Cleaning

North Carolina, Pilot Mountain State Park, Parking Lot Area

2018 | Ground Fall – Inexperience, Inadequate Belay

North Carolina, Pilot Mountain State Park, Parking Lot Area

Lead climbing carries inherent dangers regardless of the grade and amount of protection. Popular moderates might be more perilous than notoriously dangerous routes, as climbers can be more easily caught unawares on “easy” and well-protected terrain.

Powered By:

The Line: Two New Routes on the Incredible Hulk

Monica Jones on the Green Flame (5.12b), pitch five of the new route Choose Joy (IV 5.13a) on the Incredible Hulk. Photo: Abel Jones.

Already stacked with four-star alpine rock climbs, the Incredible Hulk in California’s Sierra Nevada got two more cool routes in 2024. Reports from the Hulk by Abel Jones and Jeremy Collins will be published in AAJ 2025; we’re previewing them here for those who might like to sample the goods this summer. You can find the complete reports, more photos, and topos for the climbs at the AAJ website—see the links below.

CHOOSE JOY

Chase Leary following Pitch 11 (5.12b), high on Choose Joy.

Photo: Abel Jones.

Over 15 years of exploring and countless days of dreaming led to the discovery of a new route on the tallest section of the Incredible Hulk. The basis for the route was an array of features I had spied over the years while climbing classics on the peak’s roughly 1,200-foot walls. During the COVID-19 lockdowns and California’s smoke apocalypse of 2020, my wife, Monica, and I took extended climbing trips to the area, armed with binoculars and our imaginations. We spent a lot of time gazing from the cliffs surrounding Maltby Lake, which offer a unique perspective from slightly up-canyon of the typical bivy area.

Putting a rough plan in place, I spent the next couple of years roping in various partners for ground-up exploration. We scoured the right side of the west face of the Hulk, trying to link the desired crack systems. After cruising dreamy, well-protected sections, we’d be stymied by closed seams or blank faces that forced us onto existing routes or dangerously loose terrain. We pioneered some decent pitches that led to nowhere in the area left of what became our final line, and we did a chossy 5.10 that topped out to the left of Red Dihedral, right of our final line.

Chase Leary following pitch six (5.11b) on the 12-pitch Choose Joy. Photo: Abel Jones.

With our ground-up methods exhausted, we started swinging around to seek out the highest-quality free climbing. The advice I got from other developers was to “make it classic,” and we aimed for that. I spent two summer seasons—2022 and 2023—scrubbing and equipping, primarily alone.

In the summer of 2024, my wife and I attempted the route and found it harder than expected. We had to redpoint most of the five 5.12s, cleaning and working our way up. The crux third pitch, a beautiful 5.13- splitter, was out of my league due to soaring summer temperatures and my still-developing fitness.

Monica and I worked out a 5.11 variation around the pitch, but the direct route deserved a proper send. Eventually the temperatures dropped, and with refined beta and support from one of the Sierra’s main crushers, Chase Leary, I was able to pull off a no-falls free ascent on August 28. The ascent included a thrilling runout due to skipping the gear placements I had rehearsed for the 5.13- crux—I climbed through the hardest part to a thumb jam, then barely got in a below-knee placement. I also got to witness some amazing onsighting by Chase, and the absolute glory light and stoke we had topping out the 1,200’ line.

Choose Joy (12 pitches, IV 5.13a) is a safe, no-grovel endurance route characterized by sustained 5.11 to 5.12- crack and face climbing between nice belay stances. We placed bolts where necessary. This route provided me with a ton of joy, and I hope it will do the same for others.

— Abel Jones

AAC Members Only: Download the 2025 AAJ

If you are an active AAC member, you can download a PDF of the 384-page 2025 American Alpine Journal right now and discover hundreds of new climbs. Log in to your Member Profile, look for the Publications section, and open the download link. The printed AAJ will be mailed out in September.

Have you climbed a long new route this year in the Alaska, Peru, Bolivia, or Greenland? We’re working ahead on these sections for the 2026 AAJ. Email us about significant first ascents here or anywhere in the world!

INFINITY GAUNTLET

The west face of the Incredible Hulk, showing the new routes (1) Choose Joy (5.13a) and (2) Infinity Gauntlet (5.11d). Both routes are 12 pitches. Route 3 is the classic Red Dihedral. Many other routes are not shown. Photo: Jeremy Collins.

It’s a funny story: My first time hiking in to climb the Incredible Hulk was in 2003 with my friend Allen Currano. He caught wind of a prank I was going to pull, and he found a way to meet me at my own juvenile level. We both changed into spandex Spider-Man costumes at the base and did probably the first team Marvel superhero ascent of the peak. Other lighthearted ascents followed as I fell in love with the place, including a stimulating ski-in February ascent of Beeline with Chris McNamara.

In the spring of 2024, when I sent a note to prolific Hulk climber Dave Nettle with an idea for a new line right up the middle of the face, he replied with some advice and gave his blessing: “If you are motivated, why not go explore the possibilities there? Go get it, amigo!” My longtime partner Jarod Sickler also has a Hulk crush, and he was quick to join the effort. Moi Medina, a part-time DJ and full-time history professor in Los Angeles, was headed to Tuolumne at about the same time, but when I told him what we had in mind, he quickly rerouted.

Jarod Sickler leading the bombay chimney on pitch four (5.11c). Photo: Jeremy Collins.

We left the ground with low expectations for rock quality: The line is the obvious weakness up the center, so for all we knew there was a great reason it hadn’t been climbed. Fortunately, we found the choss manageable and the short sections of crunchy rock cleaned up without too much hassle.

Starting about 100 feet left of the Red Dihedral and about 100 feet right of Tradewinds, we stayed committed to not getting pulled into the “folds” on our right, an accordion series of tight dihedrals that looked like a shattered Devils Tower. In the end, the line was mostly moderate, like its popular neighbor, with short, punchy cruxes and fantastic, airy positions. Notably, pitch four offered a tips layback (5.11c) leading into a bomb-bay chimney, and pitch five had a 5.11d boulder problem (the crux of the route) on a hanging arête.

Superheroes: Jarod Sickler, Moi Medina, and Jeremy Collins.

In all, Infinity Gauntlet (12 pitches, IV 5.11d) took us two long weekends to establish. We drilled 17 protection bolts on lead. While our primary goal was to create a quality route, our secondary goal was to create a better descent option for Red Dihedral than the standard scramble-to-single-rappel-to-loose-1,000-foot-gully option. There are 13 rap stations straight to the ground that double as belays on the way up; we added a rappel station halfway up the first 70m pitch to ensure no rap was longer than 35m.

— Jeremy Collins

THE CUTTING EDGE: MT. PROVIDENCE

The Cutting Edge Podcast returns to Alaska for Episode 70 with Anna Pfaff, Andres Marin, and Tad McCrea. This past spring, the trio completed a direct new route up the south face of Mt. Providence in the Alaska Range. The nearly 1,000-meter climb had stout difficulties on rock, ice and snow. For Pfaff, who lost six toes to frostbite on a nearby peak in 2022, the summit was a form of redemption. And on Mt. Providence, all three climbers found large doses of good fortune and serendipity. Host Jim Aikman interviewed each climber to capture this compelling story of friendship, belief, and kismet in Alaska.

Supported By:

Powered By:

The Line is the newsletter of the American Alpine Journal (AAJ), powered by Arc’teryx, with additional support from Mountain Project by onX. The line is emailed to more than 80,000 climbers each month. Find the archive of past editions here. Got a potential story for the AAJ? Email the editors at [email protected].

Sign Up for AAC Emails

2025 American Alpine Club Gala Awards

MEET THE AWARDEES

Discover their incredible stories, then join us for the 2025 American Alpine Club Gala to hear more!

The Robert Hicks Bates Award: Brooke Raboutou

"Trieste" (V14) —Red Rock National Conservation Area, NV. Photo by Jess Glassberg/Louder Than Eleven.

FOR OUTSTANDING ACCOMPLISHMENT BY A YOUNG CLIMBER

Brooke Raboutou grew up in Boulder, CO, where she began climbing at age two. At 11, Raboutou sent Welcome to Tijuana (5.14b) in Rodellar, Spain, becoming the youngest person to climb the route. From 2020 to 2022, Raboutou pushed bouldering grades, sending Muscle Car (V14), The Atomator (V13), The Shining (V12/13), The Wheel of Chaos (V13), Doppelgänger Poltergeist (V13), Jade (V14), Euro Trash (V12/8a+), Euro Roof Low Low (V13/8b) Trieste (V14), Heritage (V13), La Proue (V13), Lur (V14), Evil Backwards (V13). Raboutou was the first American to qualify for the Olympics, and during the Tokyo Olympics in 2021, she finished 5th.

In October 2023, Raboutou sent Box Therapy in Rocky Mountain National Park and promptly downgraded it from V16 to V15. In 2024, Raboutou won silver in the combined bouldering and lead competition at the Paris Olympics, becoming the first American woman to win an Olympic medal in climbing. In April 2025, Raboutou sent Excalibur (5.15c), becoming the first woman to send the grade.

David R. Brower Conservation Award: Outdoor Alliance

Crested Butte. Photo by Holly Mandarich.

FOR LEADERSHIP AND COMMITMENT TO CONSERVATION AND THE PRESERVATION OF MOUNTAIN REGIONS WORLDWIDE

Outdoor Alliance is a nonprofit coalition of national advocacy organizations that includes American Whitewater, American Canoe Association, Access Fund, International Mountain Bicycling Association, Winter Wildlands Alliance, the Mountaineers, the American Alpine Club, the Mazamas, the Colorado Mountain Club, and the Surfrider Foundation. For more than ten years, Outdoor Alliance has united the human-powered outdoor recreation community to achieve lasting conservation victories. Its work has helped to permanently protect 40 million acres of public land, secure $5.1 billion in funding for the outdoors, and convert more than 100,000 outdoor enthusiasts into outdoor advocates. Adam Cramer will be accepting the award on behalf of Outdoor Alliance. He is the founding Executive Director and present CEO of Outdoor Alliance. During his time as CEO, Adam has brought new sensibilities to conservation work that have resulted in hundreds of thousands more acres of protected landscapes, improved management for outdoor recreation, and thousands of outdoor enthusiasts awakened to conservation and advocacy work. He is an avid whitewater kayaker and mountain biker, but is always on the lookout for a good skatepark.

Honorary Membership: Jack Tackle

Chilling ll in the Kishtwar Himalaya in India in 2015. Photo by Renny Jackson.

Honorary Membership is one of the highest awards the AAC offers. The award is given to those individuals who have had a lasting and highly significant impact on the advancement of the climbing craft.

For 52 years, Jack Tackle has focused on alpine climbing, particularly first ascents, in the Himalayas, South America, and Alaska. Jack Tackle is best known for his climbing in Alaska. He has done 35 separate trips, combining both attempts and successes since 1976, and completed 17 significant first ascents in Alaska’s various ranges. Tackle is a past Board member of the AAC (nine years) and served as Treasurer of the AAC from 2009-2012. He has been a member of the AAC since 1978. He presently serves on the Pinnacle and Grand Teton Climber Ranch committees and is the chairman of the AAC Cutting Edge Grant committee. For 30 years, Tackle was an independent sales rep for outdoor brands, including Patagonia, Black Diamond Equipment, and Vasque Footwear. In addition, Tackle guided for Exum Mountain Guides in the Tetons for 40 years, from 1982 to 2022.

The H. Adams Carter Literary Award: Michael Wejchert

Michael Wejchert. Photo by Alexa Siegel.

FOR EXCELLENCE IN CLIMBING LITERATURE

Michael Wejchert began climbing as a scared ten-year-old in a swami belt. Now a scared thirty-nine-year-old, rock and ice climbing remain his overriding passion. He began writing about climbing in high school and hasn't stopped. In 2013, he won the Waterman Fund Essay Contest for a piece called Epigoni, Revisited, about a failed attempt to climb Mount Deborah in the Hayes Range of Alaska. His first book, Hidden Mountains, won a National Outdoor Book Award in 2023. His essays and features have appeared in virtually every North American climbing magazine and major media outlets: Alpinist, Ascent, Rock & Ice, Appalachia, and the New York Times, to name a few. He is a proud contributing editor at the new Summit Journal. He lives just down the road from Cathedral Ledge, New England's finest trad cliff.

The Pinnacle Award: Kelly Cordes

Kelly Cordes at the team's second bivy, Great Trango Tower, 2004. Photo by Josh Wharton.

FOR OUTSTANDING MOUNTAINEERING AND CLIMBING ACHIEVEMENTS

As an undersized kid who wanted to be a cowboy, Kelly Cordes never dreamed that climbing would define his life. But he stumbled upon an obsession that took him to places of unimaginable beauty and infused his world with meaning. He established challenging alpine routes in Alaska, Peru, Patagonia, and Pakistan along the way. Some of his notable ascents include: the first ascent of the Azeem Ridge on Great Trango Tower, Pakistan; first link-up of Tiempos Perdidos and the upper West Face ice routes on Cerro Torre, Patagonia; first ascent of Personal Jesus on Nevado Ulta, Peru; first ascent of The Trailer Park on London Tower, Alaska; first ascent of Deadbeat, Thunder Mountain, Alaska; and the first ascent of Ring of Fire, Thunder Mountain, Alaska. His personal experiences intersected with a larger journey in his award-winning book, The Tower: A Chronicle of Climbing and Controversy on Cerro Torre. Cordes was also a senior editor of the American Alpine Journal for many years. He claims to never tire of mountains and wild places.

The David A. Sowles Memorial Award: Jacques-Olivier Chevallier, Vivien Berlaud, Paulin Clovis

Photo by GMHM.

FOR UNSELFISH DEVOTION TO IMPERILED CLIMBERS

McNeill-Nott Award recipient Michaelle Dvorak and her climbing partner, Fay Manners, attempted a first ascent on Chaukhamba III (6,995m) in northern India. Falling rocks sliced their rope, sending their haul bag, with most of their gear, plummeting down the mountain. The two sent out an SOS before Dvorak’s phone died and hunkered down as a storm rolled in. They waited for rescue, but helicopters circled them without seeing them. After two days of waiting, they decided to descend on the third day. They only had one set of crampons, making the impending challenge a high-consequence affair.

Three climbers from the French Group Militaire de Haute Montagne of Chamonix, or the High Mountain Military Group, named Vivien Berlaud, Paulin Clovis, and Jacques-Olivier Chevallier had heard that two climbers were missing and abandoned their attempt on the peak’s east pillar to rescue the two climbers. The High Mountain Military Group is an elite and small unit that includes some of the best mountaineers in the French Armed Forces among its members.

The two climbers safely reached the French advanced base camp with Vivien Berlaud, Paulin Clovis, and Jacques-Olivier Chevallier's help. The Indian Mountaineering Federation (IMF) helicoptered them out the next day.

Vivien Berlaud is a sergeant of the High Mountain Military Group.

Photo by GMHM

Paulin Clovis is a member of the High Mountain Military Group. In 2023, he did the first repeat and winter ascent of Directissima (1200m 7a A2) on Pointe Walker on the north face of the Grandes Jorasses.

Jaques-Oliver Chevallier is a High Mountain Military Group member and a mountain guide. Some of his accomplishments include: the Triple Direct (975m VI 5.9 C2) on El Capitan, Yosemite Valley; Cassin Route (1200m IV 5.9+ TD+/ED1 A1) on the north face of the Grandes Jorasses; Mont Blanc with a client; and Intégrale de Peuterey (4545m VI 5.9 WI4 M5) in the Mont Blanc massif.

Angelo Heilprin Citation: Rick Wilcox

Ty Marshall, Edge of the World 5.13c, The Prow Area, Cathedral Ledge, NH. Photo by Andrew Burr.

FOR EXEMPLARY SERVICE TO THE CLUB

“Rick embodies the spirit of the Angelo Heilprin Citation through his decades of tireless service to the AAC, his instrumental role in establishing and leading critical mountain rescue operations, his entrepreneurial vision in fostering a thriving climbing community, and his dedication to our community and pursuits. It is without reservation that we select Rick Wilcox for the Angelo Heilprin Citation.” - Selection Committee.

Rick Wilcox has exemplified the dedication and service required for the Heilprin Citation for over half a century. He has been an AAC member since 1973 and served as secretary to three AAC presidents, providing invaluable continuity and institutional knowledge. He was also a member of the AAC Board of Directors and a highly active participant in the AAC New England section.

In 1976, while managing EMS in North Conway, NH, he was instrumental in establishing Mountain Rescue Service (MRS). He then served as MRS president for an impressive 41 years, leading essential rescue operations in the extreme environments of the White Mountain National Forest, which was recognized in 1999 when the New Hampshire MRS received the David A. Sowles Award for critical assistance to climbers.

Beyond his direct contributions to the AAC and mountain rescue, Wilcox purchased International Mountain Equipment in 1979, a pillar of the climbing community. Later, he co-owned International Mountain Climbing School with Brad White, which grew into a highly respected brand. In 1993, Rick, alongside Nick Yardley, co-founded the Mount Washington Valley Ice Fest, now the premier ice climbing event in the Northeast. He also had a six-year tenure as a director of the American Mountain Guides Association.

Wilcox’s unwavering dedication to the Club has benefited countless climbers for decades, particularly in the Northeast, where he has been a vital behind-the-scenes nexus.

American Alpine Club award winners will be honored with bespoke, sustainable, custom-made awards by metal artist Lisa Issenberg. Lisa is the owner and founder of the Ridgway, Colorado studio, Kiitellä, named after a Finnish word meaning to "thank, applaud, or praise." Lisa has been providing custom awards for the American Alpine Club since 2013. Kiitellä's process includes a mix of both handcraft and industrial techniques. To learn more, visit kiitella.com

Attend the 2025 American Alpine Club Gala in Denver, CO, on October 18, 2025, to hear more from these awardees.

Suffer Well: A Climbing (and Life) Philosophy, with Kelly Cordes

Every year, the AAC bestows awards to climbing changemakers and celebrates their accomplishments at the AAC Gala. We’ll be announcing those award winners in mid July, but first, we wanted to give our listeners a sneak peak into the stories awaiting you, through diving into the life and personality of one awardee. We invited the alpinist and climber Kelly Cordes, who will be receiving the Pinnacle Award this year, onto the pod to celebrate his outstanding mountaineering and climbing achievements, and simply to ramble a bit and tell good stories. Though too humble to brag, Cordes is known for his bold ascents, including the Azeem Ridge on Great Trango Tower, a link-up on Cerro Torre, many first ascents in Peru and Alaska, as well as his “disaster style” and “suffer well” philosophy. With a 20-year lens, we have Cordes reflect on the Azeem Ridge story and tell it anew with all that he’s learned since then. We also spend some time talking about his writing life, including supporting editing the AAJ for 12 years, and co-writing the bestseller, The Push, with his close friend Tommy Caldwell. Dive in to get just a taste of Cordes’ story, and why he’s committed to suffering well.

The Prescription—Rappel Fatalities

This month, we recall a tragic accident from 2023 ANAC. While recalling this accident is disturbing, it’s important to understand that there were 14 published rappel accidents that year, eight of which resulted in fatalities. The trend shows no sign of abating. In the upcoming 2025 ANAC, our data tables record a total of 15 reported rappel incidents that involved 23 climbers and ended with five fatalities. It’s not all bad news. In the 2025 ANAC, we also feature an article with tips for improved rappel safety from John Godino of Alpinesavvy.com.

The west face of Tahquitz Rock was the scene of a tragic rappel accident in 2023 when two climbers fell to their deaths after an apparently solid rappel sling broke. Photo: Benjamin Crowell—Wikimedia.

Rappel Fatalities | Broken Anchor Sling

Tahquitz Rock, Riverside County, California

On Wednesday, September 28, 2022, Chelsea Walsh (33), a documentary filmmaker, and Gavin Escobar (31), an ex–Dallas Cowboys football player, died in a fall at Tahquitz Rock (Lily Rock). The Riverside Mountain Rescue Unit (RMRU) responded to the accident and later provided an in-depth analysis. They concluded that a degraded rappel sling caused the fatal fall of several hundred feet. This was one of two fatal accidents in 2022 due to a broken rappel-anchor sling.

RMRU reported that, around 8 a.m., Escobar and Walsh told another climbing party that they intended to climb Dave’s Deviation (3 pitches, 5.9). The weather appeared good, with only a few puffy clouds. At 10:30 a.m., a team on a route to the left, Super Pooper (5.10b), saw Escobar and Walsh near the top of their route. The weather was still good.

Fifteen to thirty minutes later, it began to rain. The team on Super Pooper began talking about retreating. By noon, the weather had gotten even worse. A team on Left Ski Track (5.6) had topped out and took shelter under a rock near the top of The Trough, a four-pitch 5.4. According to the RMRU report, by this time, “(the) weather has significantly deteriorated, with thunder and heavy rain and small hail. Members of both climbing parties were surprised at how quickly the storm intensified. Water was running down rock faces and soaked all climbing gear.”

Between noon and 12:15 p.m., the team on Super Pooper began to retreat. They heard a noise from the direction of Walsh and Escobar’s route and saw two falling climbers and a very large rock falling with them. The four climbers near the top of The Trough heard the same. No one heard rockfall before the sight and sounds of the fall. When RMRU arrived, they found Walsh and Escobar at the base of a gully below The Trough. The location of the bodies aligned with the fall line below a tree that was above the finish of Dave’s Deviation. Later investigation and video taken by Walsh confirmed the pair chose the tree—with an in situ rappel sling—as a bail point. The video also showed Escobar initiating the rappel and both climbers clipped into the single webbing loop. Both climbers appeared in good spirits and unhurried in making their rappel arrangements.

Above, we see the broken sling. At the time of the accident, this sun-bleached sling appeared darker/newer because it was wet from the rain storm that caused the climbers to rappel from this spot. Photo: James Eckhardt/RMRU.

The RMRU reported that the pair were found “wearing helmets, harnesses, and climbing shoes. Chelsea had a PAS girth-hitched through her harness with a locked screwgate at the far end, an unlocked screwgate clipped to an ATC, and an unlocked screwgate clipped to a hollow block. Chelsea was not connected to the rope or any anchor material. Gavin had a single-length sling girth-hitched to his harness’ tie-in points with an unlocked carabiner clipped to the sling and the belay loop. Additionally, an ATC was attached to his belay loop with a locked screwgate and both strands of the rope running through the ATC and through the screwgate. There was a four-to-five-foot loop of rope extending from the top of the ATC with two opposite and opposed wire-gate carabiners clipped to the rope. These carabiners were not connected to anything else. The rope had some sheath damage to the area around the ATC and significant sheath damage a few feet below the ATC, but there were no breaks present. Each end of the rope had a single figure 8 tied into it, one loose and one hand tight.”

The RMRU report summarizes, “As the storm moved in, the party reached the pine tree close to the first pitch of Upper Royal’s Arch and, given the conditions, decided to rappel. By the time they reached the pine tree, the webbing [around the tree] was wet, and as such, it would have been more difficult to ascertain the quality of the webbing without closely inspecting the knot and seeing the original color. They likely clipped into the webbing with their personal anchor systems. As the terrain below the pine tree is sloping, with only small areas to stand, it is likely they would have both been weighting the webbing. They then tied stopper knots into their rope, clipped it through the two wire-gates opposite and opposed, and dropped the ends. Gavin was first on rappel and descended a few feet before the webbing broke. As it was a single strand with no redundancy, both climbers fell. There was no evidence of rockfall hitting the tree or surrounding rock, and the webbing could not have been cut by a rock.

Video Analysis—Rappel Anchors

In this video, Jason Antin, IFMGA/AMGA Guide, gives some tips to avoid mistakes at the anchor:

Avoid rappelling from a single sling.

Avoid rappelling from an anchor made of old webbing.

White or gray nylon webbing is a red flag and needs closer inspection.

Beware of blotchy or faded webbing. Inspect the knot to try to spot an alternate (original) color inside. Try turning a sling over to look at its “under” side, against a tree or chockstone.

Carry a knotted sling or cordelette to back up anchors and a knife to cut away bad webbing and carry it out.

Credits: Pete Takeda, Editor of Accidents in North American Climbing, Jason Antin, IFMGA/AMGA guide; Producer: Shane Johnson and Sierra McGivney; Videographer: Foster Denney; Editor: Sierra McGivney; Location: Little Twin Owls, Lumpy Ridge, CO.

ANALYSIS

Rappelling from a single sling is not advisable. Nor is rappelling from an anchor comprised of old webbing. That said, most experienced climbers (the editors included) have at one time or another done both. Walsh and Escobar were very experienced and, based on their video, they felt in control of the situation. While the weather played a factor in their decision to retreat, it also indirectly played a role in the team’s decision to use the questionable rappel sling. The rain had made the sling appear in much better condition than it was. The RMRU report states, “The webbing felt old and stiff when dry, but when wetted, it felt significantly better and looked much less faded. It was gray/white…however, upon retrieval and closer inspection, it had originally been fluorescent green and was now fully faded from prolonged sun UV exposure.”

The RMRU report added that, “The unfaded color was visible in the knot, however it was very difficult to see without close inspection.” Any white or gray nylon webbing at an anchor is a red flag: Such webbing is sold, but it’s uncommon, and it suggests closer inspection. The same goes for any blotchiness (from fading) in the webbing. Inspecting the knot for soundness is a good step, for obvious reasons, but possibly spotting an alternate color inside the knot is also good reason to inspect it. Also, try turning a sling over to look at its “under” side, against a tree or chockstone. These days, sewn aramid-fiber slings are the norm. It is expensive to leave behind long looped runners as rappel anchors. To get around this problem, consider carrying a long knotted sling or cordelette that is better suited for backing up suspect anchors; a knife will be handy to cut the sling to length. This solution is inexpensive and reasonably light weight. (Sources: James Eckhardt, RMRU, and the Editors.)

These are images of the failed webbing rappel anchor from Tahquitz Rock. (A) Webbing as it was found on tree, with arrows indicating the two broken ends. (B) Image showing the full length of webbing retrieved with break and (C) close-up image of break. (D) Test 1: webbing broke at 2.54kN. (E) Test 2: webbing broke at knot at 3.56kN. Image also shows the original color (neon green) of the webbing. (F) Test 3: webbing broke at 3.2kN. Photos: RMRU.

Only a Few Days Left—Get the Shirt

Accidents in North American Climbing is one of climbing’s most historic and treasured publications. Get it with your American Alpine Club Membership! For the month of June only, also get the limited edition T-shirt!

Already a member? Donate $30 or renew in the month of June!

Use promo code: DIRTBAG

Powered by:

The Line: Coveted Chinese Wall Finally Climbed

The west face of Seerdengpu, a towering rocky summit of 5,592 meters in China’s Siguniang National Park, had been attempted at least a dozen times without success. Among others, West Virginia climber Pat Goodman tried six different lines during three separate expeditions. In 2024, a Chinese climber finally topped out on the 850-meter face, in his fourth year of attempts. Unable to secure a permit, he climbed alone and in secret in August 2024, completing only the second known ascent of the peak. Below is his story.

SEERDENGPU, WEST FACE

The west face of Seerdengpu (5,592m), approximately 850 meters high. Prior to 2024, the peak had only been climbed once, in 2010, by Americans Dylan Johnson and Chad Kellogg. The west face had been attempted at least a dozen times without success. Photo: Griff.

In 2015, when I first saw Seerdengpu (5,592m) from the west, I never thought that one day I would stand on the summit. The ca 850m west face was one of the great unclimbed walls of Siguniang National Park and had been attempted many times, notably by American Pat Goodman. In 2013, with Matt McCormick, he made unsuccessful attempts on three different lines, then later another attempt with Marcus Costa, and another, more toward the southwest, with David Sharratt. Costa made another attempt with Enzo Oddo. The face had also been tried by Russian, Australian, Polish, and Chinese teams. Loose terrain and objective danger appear to have been a common problem.

Until 2024, Seerdengpu had only one ascent. In 2010, Dylan Johnson and Chad Kellogg (both USA) climbed the northeast ridge (see note below). Prior to their ascent, four parties had attempted the north face.

I first tried the west face in August 2021 but chose a poor line and retreated after 80 meters. In 2022, I changed to the previously attempted line on the right side of the wall (the line attempted by Costa and Goodman, as well as the Russian and Chinese teams). I retreated after 350 meters. Over three weeks in July 2023, I only reached 200 meters up the same line. I returned in August 2024.

Unable to get an official permit, I had to work alone, as porters did not dare provide service. [Because of this, the author is using an alias.] I entered the valley several times as a tourist, each time carrying a 40-liter bag. In the end, I ferried a total of 75kg of equipment from the road in Shuangqiao Valley to my base camp at 4,500 meters.

French climber Enzo Oddo in the ice gully on the west face of Seerdengpu in January 2015. Oddo and Marcos Costa attempted a winter ascent, hoping to avoid the rockfall danger that plagued other attempts. The ice was excellent, but two-thirds of the face still involved hazardous rock climbing. The successful 2024 ascent followed the same gully in August. Photo: Marcos Costa.

After the initial 170 meters of the face, which is 5.7, the route enters a gully. It is always wet. Some previous attempts had failed due to the volume of water, and in 2015 Costa and Oddo tried this route in January, finding the gully nicely frozen but the rock above dangerously loose. They retreated from the Russian high point. I kept mostly in the bed of the narrow gully, which was wet and loose, but easier (5.8 C1+). I made my first portaledge camp at the top of the gully at around 5,100 meters.

On the first day above the portaledge, I climbed 80 meters at 5.9 C1+. When I rappelled to the ledge that evening, I found two holes in the fly, one of them large. A small bag on the ledge had also been hit and damaged. The next day, I climbed up left on loose but easy rock (5.6), found a site for my next camp, and spent all the following day moving my equipment to Camp 2 (5,250m).

On August 24, I aided a horizontal crack and took the only fall of the route. I retreated and took a different line, a corner with a thin crack that evolved into a chimney. It was a brilliant 60m pitch at 5.9+ C2. (I suspect it would go free at 5.11 or 5.11+.) Above this, I traversed left using all my 70m rope, then went back to the portaledge for the night. I found it difficult to sleep due to the cold, and perhaps the excitement of being close to the top.

On the 25th, I regained my high point and continued up at 5.8 C1+. That day I dropped an ascender, a Camalot, and a sling. I realized that I was losing concentration and needed to be more careful. That night, I didn’t get to sleep until 3 a.m. I was sick and cold. I left Camp 2 again at 8 a.m. on August 26—a total of 27 days since I first started ferrying loads from the road. I reached my high point at 11 a.m. and climbed for a further 150 meters to the top of the face. From there I walked 200 meters over ice and boulders to reach the highest point of the mountain, at 2:55 p.m., for its second ascent.

Close-up view of the first ascent of the west face of Seerdengpu. The wall is about 850 meters high, and the climbing distance of the route totaled about 1,200 meters. Photo: Griff.

Unfortunately, just 50 meters before reaching the summit, a loose boulder fell onto my left foot and broke a toe. As I started back down, it began to rain. Four hours of rappelling through rain and sleet took me back to the portaledge. My foot was painful and didn’t look good, so I decided I should get off the mountain the next day and called friends to let them know.

On the 27th, I threw some gear and the portaledge off the wall and rappelled from 11:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., reaching base camp that day. A few days later I was in a Beijing hospital, having an operation on my toe. My friends later collected my gear from base camp.

I named the route Wild Child. It has around 1,200 meters of climbing up to 5.9+ C2. I did not carry a bolt kit, but there are five bolts in the initial gully, all installed by a 2014 Chinese team for rappel anchors. Higher, there is one bolt at Camp 1, thought to have been installed by the Russian team.

—Ma Fang, China

Editor’s Note: Because he climbed without a permit, the author of this report used a pseudonym for his AAJ story.

Only a Few Days Left—Get the Shirt

The American Alpine Journal is one climbing’s most historic and treasured publications. Get it with your American Alpine Club Membership! For the month of June only, also get the limited edition t-shirt!

Already a member? Donate $30 or renew in the month of June!

Use promo code: DIRTBAG

SEERDENGPU: THE FIRST ASCENT

Seerdengpu from the north, with the line of the first ascent by the northeast ridge (mostly hidden). The "nose", unsuccessfully attempted by several teams, divides shadow and sunlight. The west face, climbed in 2024 for the mountain’s second ascent, is partially in view to the right. Photo: Dylan Johnson.

American climbers Dylan Johnson and Chad Kellogg made the first ascent of Seerdengpu in 2010, two years after climbing a new route up nearby Siguniang. On their third attempt in 2010, the pair climbed the northeast ridge of Seerdengpu in a 34-hour round-trip push from their high camp. It was Johnson’s third summit in the Qionglai Mountains and Kellogg’s seventh. Tragically, Kellogg died less than four years later in a rockfall accident in Patagonia. Johnson’s report about the Seerdengpu climb appeared in AAJ 2011: Read it here.

Powered by:

Supported by:

The Line is the newsletter of the American Alpine Journal (AAJ), powered by Arc’teryx, with additional support from Mountain Project by onX. The line is emailed to more than 80,000 climbers each month. Find the archive of past editions here. Got a potential story for the AAJ? Email the editors at [email protected].

2025 Climbing Accident Trends: What the Data Tells Us

It’s that time of year again–the AAC has invited the editor of Accidents in North American Climbing, Pete Takeda, to hop on the pod to chat about emerging trends in climbing accidents. This year, we’re also delighted to have a conversation with Dr. Valerie Karr, a professor at UMASS who has stepped in to help us with a massive data analysis project. Valerie used grounded theory analysis to parse through 20 years of accidents data—picking out patterns in how human behavior contributes to accidents. We discuss some examples like risk normalization, the mentor trap, and attitudes around fixed gear. Dive into the podcast to hear about her findings and learn more about the case studies that stuck out to the editors this year.

Guidebook XIV—Policy Spotlight

Photo by AAC member Kennedy Carey.

EXPLORE—An Act and The Act

By AAC Advocacy Director Byron Harvison

Photos by AAC member Kennedy Carey

Act

1. A thing done; a deed.

2. A written ordinance of Congress, or another legislative body; a statute.

3. A main division of a play, ballet, or opera.

Drama

1. A play for theater, radio, or television.

2. An enticing, emotional, or unexpected series of events or set of circumstances.

EXPLORE, in the waning days of the 118th Congress, met every definition of the words “drama” and “act” as it made its way into becoming law. As I sat at my computer watching Senator Joe Manchin ask for unanimous consent of the bill on the Senate floor, it was not lost on me that years of work, by hundreds of organizations, teetered on the edge of achievement. And it passed in a most glorious fashion. But let me back up just a bit...

Act 1, Scene 1

Not too long ago, in early December of 2024, the AAC policy team traveled to Washington, DC, and met up with the Access Fund and American Mountain Guides Association (AMGA). The mission was clear—examine and pursue all avenues to get the EXPLORE Act passed. At that time, attachment to the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) was still on the table, as was the possibility of being bundled in with the Continuing Resolution (CR) to keep the government funded. Additionally, there was the less probable route of the bill going “stand-alone” for a unanimous consent vote on the Senate floor, but we sensed that there wasn’t enough floor time, especially given the need to end the lame-duck session of Congress, and the condition that a unanimous consent vote had to actually be unanimous without a single dissenting vote.

Photo by AAC member Kennedy Carey.

It was an all-hands-on-deck moment for recreation-based organizations—Outdoor Alliance, Outdoor Recreation Roundtable, Surfrider, The Mountaineers, IMBA, Outdoor Industry Association, organizations representing hunting and fishing interests and RV interests, and many, many more orgs, all working simultaneously in an effort to see this historic recreation bill package passed.

Our small team focused a lot of effort on speaking with the bipartisan group of 16 senators that submitted a joint letter to the Secretaries of Agriculture and the Interior expressing the appropriateness of fixed anchors in Wilderness and wanting a report on the status of the agencies’ respective proposed fixed anchor regulations. The Protecting America’s Rock Climbing (PARC) Act, a component of the EXPLORE Act that serves to recognize recreational climbing (including the use, placement, and maintenance of fixed anchors) as an appropriate use within the National Wilderness Preservation System, further emphasized the intent of those senators, and of Congress more broadly, to preserve the historical and well-precedented practice of fixed anchor utilization in Wilderness.

Scene 2

It is no secret that the waning days of the 118th Congress were fairly chaotic. Characterized by the forthcoming change of administrations, few clear “unified” priorities, and the pending departure of several longtime members of Congress, the landscape was hard to navigate. We left DC understanding the potential pathways to passage of EXPLORE, but still not certain which vehicle would get it across the finish line. The following week we saw it miss the cut for the NDAA Manager’s Amendment and concentrated on advocating for its inclusion in the CR. As the days drew closer to a potential government shutdown, we came to understand that the CR was likely going to be relatively tight compared to previous iterations, and would probably not allow for bills such as EXPLORE to ride on it. The CR was out for us. That is when we heard that Senator Joe Manchin (I-WV) was considering introducing EXPLORE as a stand-alone bill.

Photo by AAC member Kennedy Carey.

This was INCREDIBLE news. However, we had some concerns as we knew that the Senate was working off of the House-passed version, which had been passed via unanimous consent (UC) in April of 2024, stewarded by Rep. Bruce Westerman (R-AR). We understood that the Senate wanted the House to address some issues in the bill, but that would require the bill to be sent back to the House for consideration and a vote...which would require time. And there wasn’t any.

On the morning of December 19, we heard that Senator Manchin was planning to introduce the House version of EXPLORE on the Senate floor for a UC vote. For those tuning into the live broadcast, we had no idea what time the possible introduction would occur. It was observable that Senator Manchin was talking to a group of senators and then left the floor. A few hours later Senator Manchin appeared and presented the EXPLORE Act for consideration via a UC vote. During his introduction, he emphasized that the EXPLORE Act was “...something that we all agree on” and that “the House and Senate are in agreement,” and that there were some changes that needed to be made but could be accomplished during the next Congress. Now keep in mind, in order to pass via UC there cannot be a single vote of dissent.

Scene 3

After Senator Manchin teed the bill up for a vote, Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) stepped up to the podium. He began by reserving his right to object until the end of his speech. This is to say that no one knew whether he would be objecting and opposing the UC of EXPLORE or allowing it to pass. He spoke to his TAKE IT DOWN Act, which is a bill seeking to protect victims of deepfake pornography. The years of work on all the bills associated with EXPLORE hung in the balance—all the work on SOAR, BOLT, VIP, and Recreation Not Red Tape, on the precipice of passage. You can imagine all the breaths that were being held while Senator Cruz spoke.

“I do not object.”

Those words, spoken as a favor to retiring Senator Manchin and Rep. Westerman, provided true theater drama that we are generally accustomed to watching in a much different environment. The historic EXPLORE Act was passed, via unanimous consent through the Senate, and was on its way to the president. On January 4, 2025, President Biden signed the EXPLORE Act into law, and it became Public Law Number 118-234.

Act 1, Scene 3, complete.

Act 2

As EXPLORE was being teed up for a vote in the Senate, the National Park Service quietly announced that it was withdrawing its proposed fixed anchor guidance. This gesture suggests a new window of opportunity for climbing organizations, as well as other interested recreation and search and rescue organizations, to work in collaboration with land agencies to develop sound fixed anchor policies that reflect the direction of Congress and their passing of the PARC Act.

The AAC Policy Team and the Executive Director have visited DC over the last two months, working carefully with our partner organizations in these quickly evolving times to support the implementation of EXPLORE, discuss impacts on our public lands as a result of the federal reductions in force, and address other issues.

Stay tuned on the AAC’s digital platforms to learn more about the status of public lands policies, and how they impact, or may impact, climbers.

Sign Up for AAC Emails

Guidebook XIV—An Interview with Dougald MacDonald

Photo by AAC staff Foster Denney.

How would you describe the scope of the work that goes into making the American Alpine Journal (AAJ)?

Dougald MacDonald: Producing the AA J is a year-round effort that involves literally hundreds of people. The actual “staff” of the AAJ (who are all part-timers and volunteers) includes more than 15 people, and each year we work with roughly 300 individual climbers and photographers to share their stories.

The book goes to press in late April, so the peak of the cycle is in March and April. But the work on the following year’s edition starts immediately, plus we prepare and upload online stories all year round. AND we produce The Cutting Edge podcast and the monthly Line newsletter.

What’s the history of the AAJ? How has it changed over the years?

DM: The AAJ is coming up on its 100th birthday, and unsurprisingly it has changed quite a lot over the years. It started out as much more of a Club publication, telling the stories of AAC members’ adventures. In the 1950s, with the rise of Himalayan climbing, the book started to become much more international. But it was really Ad Carter—who edited the AAJ for 35 years, starting in the 1960s—who created the wide-ranging, international publication it is today. We no longer focus mostly on the activities of AAC members—though we’re very happy to tell those stories when we can—but instead try to document all significant long routes and mountain exploration anywhere in the world, by climbers from every country.

For both the AAJ and Accidents in North American Climbing (ANAC), the most significant changes of the last 10 to 15 years have been 1) the introduction of color photography throughout both books and 2) the launch of the searchable online database of every AAJ and ANAC article ever published.

Dougald questing off in Lumpy Ridge, Rocky Mountain National Park, CO. Land of the Cheyenne people. Photo by AAC member and former AAJ senior editor Kelly Cordes.

What’s an example of a unique challenge the editors have to deal with when making the AAJ?

DM: One challenge is that we come out so long after many of the climbs actually happened. So, readers may have seen something about any given climb several times, in news reports and social media posts and even video productions. But the AAJ has never been in the breaking news business. Instead, we aim to provide perspective and context. Perspective in that we don’t have any vested interest that might slant a story one way or another, and context on the history and geography that helps readers really understand the significance of a climb, how it relates to what’s been done before, and what other opportunities might be out there. Another big challenge is language barriers, since we work with people from all over the world. We’re fortunate to work in English, which so many people around the world use these days. We also use skilled translators for some stories, and online translation tools have improved dramatically in recent years. But there’s still a lot of back-and-forth with authors to ensure we’re getting everything just right.

What’s an example report that was really exciting for you to edit from the last few years?

DM: For me, personally, the coolest stories are the ones that teach me about an area of the world—or a moment in climbing history—that I knew nothing about before starting to work on a story. In the upcoming book, for example, we have stories about winter climbing in Greece (who knew?) and a mountain range in Venezuela that’s gorgeous and has peaks over 16,000 feet. Unfortunately, that range is rapidly losing its snow cover and its small glaciers. AAJ senior editor Lindsay Griffin, who is editing the story, did some cool climbs in the range in 1985, and the difference between his photos and those from today is shocking.

Are there any big differences in process between making the AAJ and ANAC?

DM: The biggest differences are just the scale and scope of the two books: The AAJ is a nearly 400-page book that tries to cover the entire world, and ANAC averages 128 pages and focuses on North America. There’s also a sense of starting from scratch on lots of AAJ reports, since the mountain or area in question may be entirely unfamiliar to the editor handling a story, whereas most of the accident types are all too familiar. Still, there’s always something new to learn in both books, and that makes the work very interesting and rewarding.

What emotions are you wrestling with when you ultimately send off this book to the printer?

DM: One word: relief! But also a lot of pride for what we accomplish.

Friends of the AAJ and Accidents

The American Alpine Journal and Accidents in North American Climbing are more than publications—they are the home to essential climbing knowledge. The AAJ is the sport’s definitive collection of cutting-edge climbing reports, and Accidents is the most in-depth accident analysis available to the climbing community. These publications are some of our most treasured member resources, and YOU make them possible!

By joining Friends of the AAJ and Accidents, you ensure these essential educational tools continue to inform and inspire climbers everywhere.

With a designated gift of $250 or more, you’ll be recognized as a key supporter with your name printed in the corresponding 2026 publication—publicly demonstrating your commitment to the climbing community. Friends of the AAJ also receive a signed hardcover edition of the book! When making your gift, please denote which publication you are supporting. Questions? Reach out to the team at [email protected].

Your support makes these world-renowned books possible every year! Go above and beyond for climbing inspiration and education today!

Sign Up for AAC Emails

Guidebook XIV—Member Spotlight

Photo courtesy of the Grunsfeld Collection.

No Mountain High Enough

The Intersections between Space Travel and High-Altitude Mountaineering

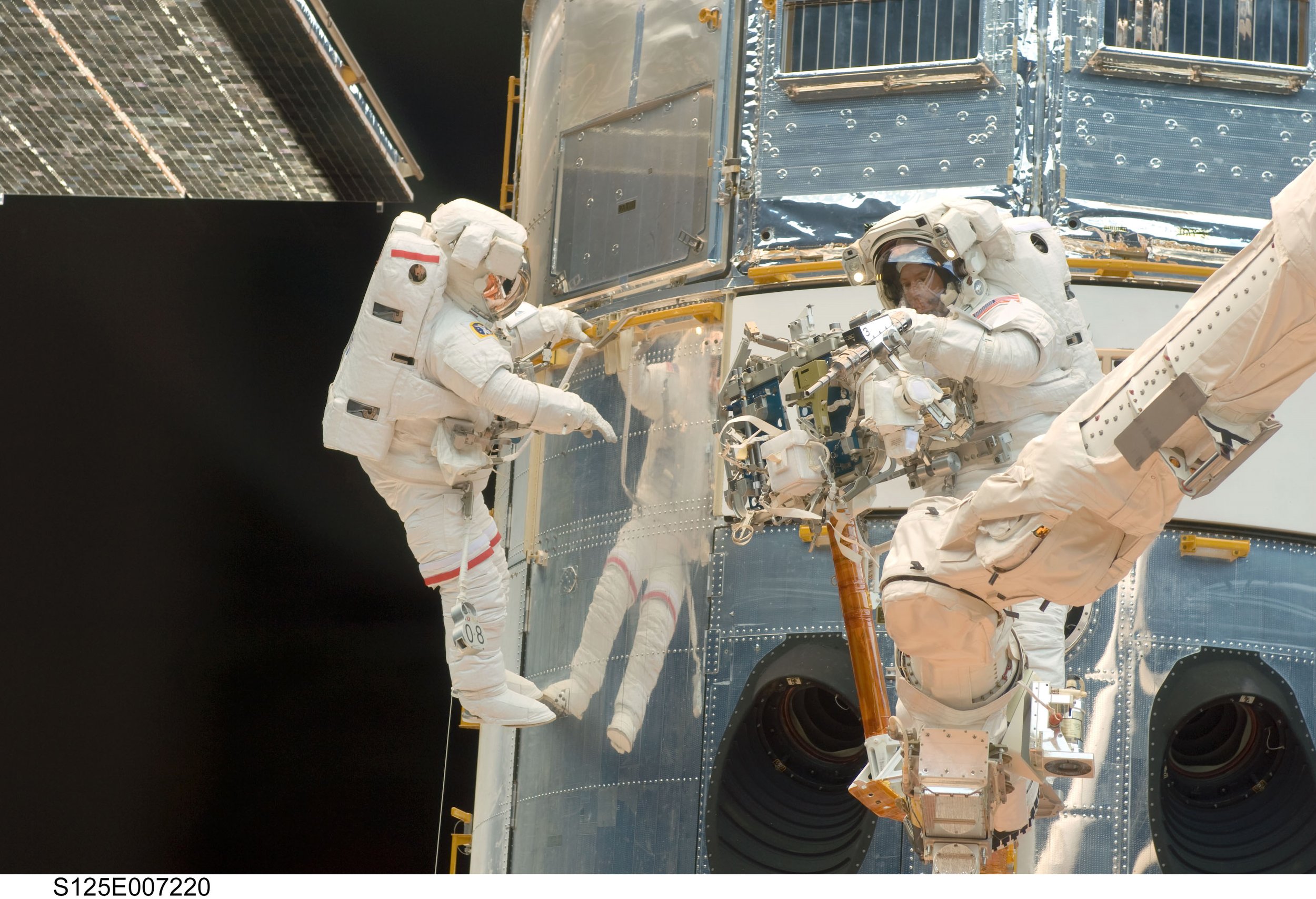

Member Spotlight: Dr. John Grunsfeld, Astronaut

By Hannah Provost

Spacewalking outside the Hubble Space Telescope, John Grunsfeld wasn’t that much closer to the stars than when he was back on the surface of Earth, but it certainly felt that way. The sensation of spacewalking, of constantly being in freefall, but orbiting Earth fast enough that it felt like weightlessness, was more of a thrill than terrifying. Looking out to the vaster universe, seeing the moon in its proximity, the giant body of the sun, stole his breath away. Grunsfeld was experiencing a sense of exploration that very few humans get to. It was deeply moving, a sensation he also got in the high glaciated ranges when he’d look around and be surrounded by crevasses and granite walls of rock and ice. Throughout his life, he couldn’t help but seek out the most inhospitable places on the planet, and even beyond.

You might think that there is nothing similar between climbing and spacewalking. But when you ask John Grunsfeld, former astronaut and NASA Chief Scientist—and an AAC member since 1996—about the similarities, the connections are potent.

The focus required of spacewalking and climbing is very much the same, Grunsfeld says. Just like you can’t perform at your best on the moves of a climb high above the ground without intense focus on the next move and the currents of balance in your body, so, too, suited up in the 300-pound spacesuit, with 4.3 pounds per square inch of oxygen, and 11 layers of protective cloth insulation, you still have to be careful not to bump the space shuttle, station, or telescope as you go about the work of repairing and updating such technology—the job of the mission in the first place. Outside the astronaut’s suit is a vacuum, and Grunsfeld is not shy about the stakes. “Humans survive seconds when vacuum-exposed,” he says. With such high risks, it’s a shame that the AAC rescue benefit doesn’t work in space.

Not only is spacewalking, like climbing, inherently dangerous, it also requires intense focus, and it can be a lot like redpointing. Grunsfeld reflects that “it’s very highly scripted. Every task that you’re going to do is laid out long before we go to space. We practice extensively.” In Grunsfeld’s three missions to the Hubble Space Telescope, his spacewalks were a race against the clock—the battery life and limited oxygen that the suit supplied versus the many highly technical tasks he had to perform to update the Hubble instruments and repair various electronic systems. It’s about flow, focus, and execution—skills and a sequence of moves that he had practiced again and again on Earth before coming to space. Similarly, tether management is critical. Body positioning, and not getting tangled in the tether, is important in order to not break something—say, kick a radiator and cause a leak that destroys Hubble and his fellow astronauts inside. But to Grunsfeld, the risk is worth it. The Hubble Space Telescope is “the world’s most significant scientific instrument and worth billions of dollars. Thousands of people are counting on that work.”

Indeed, perhaps a little more is at stake than a send or a summit.

Grunsfeld climbing at Devil’s Lake, WI. Land of the Myaamia and Peoria people. Photo by AAC member Tom Loeff.

Growing up in Chicago, Grunsfeld’s mind first alighted on the world of science and adventure through the National Geographic magazines he devoured, and a school project that had an outsized effect. Grunsfeld’s peers were assigned to write a brief biography of people like George Washington and Babe Ruth. Rather than these more familiar figures, Grunsfeld was assigned to research the life of Enrico Fermi—a nuclear physicist who was instrumental in the Manhattan Project, the creator of the world’s first artificial nuclear reactor, and a lifelong mountaineer. Suddenly, science and the alpine seemed deeply intertwined.

Grunsfeld started climbing as a teenager, top-roping in Devil’s Lake, back when the cutting edge of gear innovation meant climbing by wrapping the rope around your waist and tying it with a bowline. Attending a NOLS trip to the Wind River Range and further expanding on his rope and survivor skills truly cemented his love of climbing in wild spaces. Throughout the years, climbing was a steady beat in his life, a resource for joy. He would climb in Lumpy Ridge, the Sierra, the White Mountains of New Hampshire, Tahquitz, Peru, Bolivia, and many other places with his wife, Carol, his daughter, and close friends like Tom Loeff, another AAC member.

If climbing was a steady beat, his fascination with space and astrophysics would be a starburst. At first, his application to become a NASA astronaut was denied, but in 1992, Grunsfeld joined the NASA Astronaut Corps. It would shape the rest of his life’s work. Between 1995 and 2009, Grunsfeld completed five space shuttle flights, three of which were to the Hubble Space Telescope—which many consider to be one of the most impactful scientific tools of modernity, because of how its 24/7 explorations of space have informed astronomy. On these missions, Grunsfeld performed eight spacewalks to service and upgrade Hubble’s instruments and infrastructure. Over the course of his career, he has also served as the Associate Administrator for Science at NASA and the Chief Scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC. His own research is in the field of planetary science and the search for life beyond Earth.

Grunsfeld [left] and team on the summit of Denali (Mt. McKinley), Denali National Park, AK. Photo provided by Grunsfeld Collection.

But in 1999, even with two space missions under his belt, Grunsfeld couldn’t get the pull of high-altitude mountaineering out of his mind. He has an affinity for the adventure of exploring some of the most adverse places humans have ever explored. He was ready for his next great adventure. He wanted to climb Denali (Mt. McKinley).

Many aspects of Grunsfeld’s Denali saga are familiar. Various trips resulted in unsuccessful summit attempts: from a rope team he didn’t fully trust, to eight days at the 17,000-foot high camp with bad weather. On his 2000 attempt, he was followed around by cameras for a PBS special that never came to fruition, and he attempted an experiment about core temperatures in high-altitude terrain using NASA technology. Ultimately the expedition came back empty-handed—without a summit and with a faulty premise for their measurements of core temperature. When he returned in 2004 with a team of NASA colleagues, Grunsfeld was able to stand atop Denali and take in the jagged peaks all around him.

The connections between climbing and space travel aren’t limited to the physical demand, focus, and calm required. Both activities are inherently dangerous, and nobody participating in either of these activities has been left unscathed. Just like how many climbers have had a friend or an acquaintance experience a significant climbing accident, Grunsfeld knew the true danger of space travel. In 2003 while Grunsfeld was still in Houston, one of the most tragic space shuttle disasters in American space history occurred. On reentry into the atmosphere, the space shuttle Columbia experienced a catastrophic failure over East Texas. According to NASA’s website, the catastrophic failure was “due to a breach that occurred during launch when falling foam from the External Tank struck the Reinforced Carbon Carbon panels on the underside of the left wing.” Grunsfeld was the field lead for crew recovery—picking up the pieces of the disaster so as to bring the bodies of the lost crew members home. It’s no wonder that in other parts of his life and in his climbing, he is deeply committed to safety and disseminating as much climbing knowledge as possible about safety concerns.

After the Columbia disaster, Grunsfeld was often asked why he would consider going back to space when the risks were so high. On his final flight to the Hubble Space Telescope in 2009, Grunsfeld reports, there was a 62% probability that he and his team would come back alive. Those aren’t the most inspiring mathematical odds. But as a crew, and for the agency NASA, it was critical to update the technology on the Hubble Space Telescope at that time. He reflects: “It may seem crazy to fly with those odds, but in fact my earlier missions were much more risky, we just didn’t know it at the time.” In comparison, risk assessment in the mountains is considerably more individualized.

Space exploration and mountaineering also have a distinct investment in monitoring the state of our natural landscapes and environment. From space, it’s a lot easier to see how fragile and small Earth is, in the grand scheme of things. It’s also easier to see the changing climate and its impact across the planet. Putting on his scientist hat, Grunsfeld tried to capture the significance of space observations to climate research, saying, “Most of what we know about our changing climate is now from space observations, because we get to see the whole Earth all the time, and you really have to look at sea level not as a local phenomenon, but [look at] how does it change over a whole Earth for a variety of different reasons.”

From sea level rise to vanishing bodies of water, Grunsfeld has seen some dramatic changes to Earth’s surface from the first time he was in space, in 1995, to his last time in 2009. With his decades of exploration in the mountains, he’s also seen glaciers and once permanent snowfields disappear. You can tell from the passion in his voice that Grunsfeld has a keen awareness of what’s at stake as the climate changes—he’s seen it happening already.

In addition to bringing Grunsfeld to incredible places, climbing also brought him into close connection with incredible people. Grunsfeld had originally met the famous photographer, and fellow AAC member, Brad Washburn through AAC annual meetings and at Boston’s Museum of Science, where Washburn was the director for many years. Their friendship would result in two incredibly rare moments for climbing, photography, and space exploration.

Photo provided by the Grunsfeld Collection.

Washburn, the raspy-voiced photographer who was excellent at pulling off the unbelievable, was working on a documentary recreating the famous journey of the explorer Ernest Shackleton when he called up Grunsfeld for a favor. For the film crew to cross the mountainous, cold, and deeply unfriendly landscape of South Georgia just like Shackleton did in 1916 was still an incredibly unlikely feat. Luckily, Grunsfeld had what you might call “pull.”

“I was able to get space shuttle photography from a classified DOD shuttle flight which flew over South Georgia and made these huge prints for Brad,” Grunsfeld says—ultimately giving Washburn and his team the information they needed to safely traverse this rugged terrain.

But that wasn’t the end of Grunsfeld and Washburn’s story. Grunsfeld was attempting Aconcagua in 2007 when Barbara Washburn called to share the news that her husband had passed away. When Grunsfeld landed back in the States and was able to connect with Barbara on the phone, he offered to do something to honor his relationship with Washburn. His 2009 space mission was coming up, and he could take something of Washburn’s along. In the end, Grunsfeld brought Washburn’s camera from the famous Lucania expedition on his last flight to the Hubble Space Telescope. The 80-year-old camera (at the time) was used to take photographs from Hubble, including an image of the Hubble Space Telescope with Earth’s rim in the background, as seen on the back cover of this Guidebook. Washburn’s camera and the prints of the photos that Grunsfeld took remain as some of the AAC Library’s most fascinating holdings in the climbing archives.

But in fact, Grunsfeld’s (and Washburn’s) story isn’t the first to connect the vastly different fields of astrophysics and mountaineering. Lyman Spitzer, a longtime AAC member and supporter of the Club, and a prolific mountaineer, is credited for the idea that led to the Hubble Space Telescope. It almost makes Grunsfeld’s life’s work seem written in the stars.

Surprisingly, Grunsfeld reflects that there is little time for fear in space travel. Take launch, for example. The astronauts in the space shuttle are sitting on “four and half million pounds of explosive fuel,” says Grunsfeld, ticking down the seconds until they are launched into space. The launch mechanics are so powerful that within eight and a half minutes, the shuttle is traveling 17,500 miles per hour, orbiting Earth. Grunsfeld recalls that on his first mission, sitting in the flight deck of space shuttle Endeavor, at 30 seconds to launch, he heard the final instructions over the intercom: Close your visor, turn your oxygen on, and have a good flight. Was this the point he was supposed to get scared? There was no turning back, no getting off, no stopping the ride. So he didn’t let fear in. There was no use for it. And at the same time, there was so much awe that despite the risk, he felt deeply alive. It was a lot like the calm that comes with executing in the face of danger when climbing or in the mountains. In the face of danger, utter clarity.

With the focus and body awareness and rehearsal, the firsthand witnessing of our changing climate and its impacts, the risks involved and the utter sense of awe, space-walking and climbing are not as different as they might at first seem. And for Grunsfeld, one adventure could fuel another. In his downtime floating within Hubble, one of his favorite activities used to be looking back down on Earth, using a camera with a long lens to zoom in on various alpine regions—and scout the next mountain to climb.

The Yosemite Big Wall Permit System: Impact and Logistics

Nico Favresse, Yosemite, US, Alien Finish 12b, Rostrum. PC: Jan Novak.

Climbers and other visitors who plan on entering Yosemite National Park between 6 a.m. and 2 p.m. from June 15 thru August 15, 2025, or during Memorial and Labor Day weekends, will require reservations. Visitors holding a Half Dome or wilderness permit, in-park camping or lodging reservations, or entering on a regional or tour bus will be exempt from reservation requirements. Reservations will be available on Recreation.gov beginning on May 6, 2025 at 8 a.m. PDT, with additional reservations becoming available 7 days prior to any arrival date. Reservations will cost $2, and each visitor will be allowed to make two entry reservations per three-day period.

Yosemite's iconic granite walls draw climbers, hikers, and outdoor recreationists from all over the world. Big wall climbers spend long days on El Cap and Half Dome above the valley floor, attempting free ascents or classic aid climbs. Due to the park's growing popularity, reservations and permit systems have been implemented. Climbing is no exception.

In 2021, Yosemite NPS began a two-year big wall permit system pilot program in hopes it would help climbing rangers understand patterns on the wall and minimize negative impacts on the landscape through education. In January 2023, the permit program became permanent, and now all climbers staying overnight on big walls are required to have a permit.

PC: Andrew Burr

As with everything in the climbing community, there has been a lot of discourse surrounding this, as seen on Reddit and Mountain Project threads over the past couple of years. Climbers speculated: Would the rangers be enforcing a quota? Would these permits be available 24/7, or would reservations need to be made in advance? Would climbers have to use the dreaded recreation.gov?

Through the permit system, big wall permits are free and available for climbers to self-register 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, near the El Capitan Bridge at a kiosk near the food lockers. There is no quota for routes.

In addition to timed permits, during peak hours (6 a.m. and 2 p.m. on Memorial Day weekend, any day between June 15 and August 15, or Labor Day weekend), climbers must make reservations to enter the park. This is a timed entry reservation that is also used at other parks, such as Zion National Park, Rocky Mountain National Park, and Arches National Park, allowing the park to regulate the influx of visitors.

There is no formal check-in with the rangers after climbing (or bailing). Yosemite climbing rangers and stewards use the information they gather from the permit system to update an Instagram account that reports on big wall traffic. The Instagram's daily posts include information for the number of people on popular climbs like Freerider/Salathe, Zodiac, and Regular Northwest Face of Half Dome.

"It is a work in progress, but we are trying to find a sustainable way to get that information out to climbers so that people can disperse from crowded routes if they want," said Yosemite Climbing Ranger Cameron King. The feedback the rangers have received on the account has been positive.

Below, we've created a guide to help you navigate your next Yosemite trip filled with all the fine print and details to minimize route finding off the wall.

How To Climb a Big Wall in Yosemite: A Checklist

PC: Andrew Burr.

How to Get Your Wilderness Big Wall Climbing Permit

Permits are free, and there is no quota. Climbers can self-register 24 hours per day, 7 days per week, at a kiosk near the food lockers near El Capitan Bridge.

You can pick up your permit the day before or the day of the start of your overnight climb. This allows for more in-person education opportunities but doesn't limit climbers to "office hours."

Up to eight people can be on a wilderness climbing permit.

There is some flexibility, so you're not locked in! If the trip leader, formation, route, and dates remain the same, and the maximum number of people specified on the permit is not exceeded, things can change last minute.

If the number of people on the permit changes, the trip leader is not required to change the permit, and it will still be valid.

The permit system is not held to a quota, so there is no need to fill out the permit for the maximum number of people if you are unsure about the number of climbers in your party. The rangers encourage folks to be as accurate as possible when filling out the permit.

You don't want to miss this: Climbers with a Wilderness Climbing Permit are eligible to spend one night before and one night after an overnight climb in an open backpacker's campground.

The cost is $8 per night (per person); reservations are not required.

Tent camping only, no sleeping in your car.

For 2025, White Wolf campground is closed, and Tuolumne Meadows is set to open in August.

The Fine Print from Yosemite NPS:

Except for the base of Half Dome, camping at the base of any Yosemite Valley Wall is prohibited. Camping on top of Half Dome is also prohibited. You must be at least one topo pitch above ground level before you can bivouac on the wall.

When camping in legal areas or at the base or summit of walls, select previously impacted sites or durable surfaces. Trampling vegetation is prohibited.

Fires are prohibited at the summit and base areas of all Yosemite Valley Walls (Half Dome, El Capitan, Washington Column, etc.)

Packing out your solid human waste from the wall is required. You must have an adequate container to carry your human waste from the wall. Once you have finished, you cannot leave your human waste (or container) unattended—dispose of waste properly in dumpsters (wag bags, etc.) or pit toilets (paper/waste only). Consider packing out urine from popular routes/bivy sites as well.

Carry out all trash. Water bottles are considered trash if left behind.

Proper food storage is mandatory. All food must be hung on the wall at least 50 feet above the base of the route in 5th class terrain (or Aid). Do not leave food unattended while shuttling loads for your climb. On the summit of walls, you can either: 1) Store your food in a bear resistant canister or 2.) Hang food at least 50 feet over the edge. Do not hang your food in trees. Report any bear incidents to the nearest ranger or by calling 209.372.0322.

You are not permitted to leave ropes unattended for over 24 hours. If you are "working" a route, remove ropes after you are finished for the day. Be considerate of other climbers, and refrain from fixing lines on popular routes. All fixed ropes and caches must be labeled with name, date, and contact information, and will be removed if left unlabeled or abandoned.

The use or possession of a motorized drill is prohibited.

The Iconic Camp Four and Other Camping Options:

Nick Sullens, and Will Barnes, lat minute prep before heading to the Captain., Yosemite NP. PC: Jeremiah Watt.

To stay at Camp Four during peak season, make a reservation: https://www.recreation.gov/camping/campgrounds/10004152

Outside of peak season (October 28, 2024 - April 14, 2025), the campground is first-come, first-serve.

You don't want to miss this: Climbers with a Wilderness Climbing Permit are eligible to spend one night before and one night after an overnight climb in an open backpacker's campground.

The cost is $8 per night (per person); reservations are not required.

Tent camping only, no sleeping in your car.

For 2025, White Wolf campground is closed, and Tuolumne Meadows is set to open in August.

In a calendar year, people can only stay for 30 nights in Yosemite National Park. From May 1 to September 15, the camping limit is 14 nights, and only seven nights can be in Yosemite Valley or Wawona.

AAC Inspiration:

From the AAC Library

Guidebooks:

To Stoke the Upcoming Adventure:

According to the National Park Service, more than 100 accidents occur in the park each year. Here are some select accidents to avoid from Accidents in North American Climbing:

AAC Podcasts for the Road Trip:

PROTECT: Amity Warme and a YOSAR Climbing Ranger Weigh In on The Yosemite Credo

CLIMB: Babsi Zangerl’s Secret to Her Exceptional Yosemite Resume

EDUCATE: Hazel Findlay on Yosemite, Magic Line, and the Theory of Flow

The Climber's Credo aims to provide the Yosemite climbing community and land managers with a tool to promote Yosemite's minimum-impact climbing ethics to protect the park's Wilderness and climbing culture.

Further questions?

PC: Andrew Burr

Find information on current conditions throughout the park here, and the forecast updated here.

Call a climbing ranger at (209) 354-2025 or email a ranger through the contact us form.

During the busy season, climbing rangers are available at the Ask-A-Ranger climber program at El Capitan Bridge from 12:30 p.m. to 4:30 p.m. for more in-depth big wall leave no trace and climbing technique advice, safety tips, and route condition information.

Looking for daily updates on Yosemite's big wall traffic?

Guidebook XIV—Rewind the Climb

David Hauthon on Directissima (5.9), The Trapps, Shawangunks, New York. Land of the Mohican and Munsee Lenape people. Photo by AAC member Francois Lebeau.

Setting the Standard

By the Editors

Before there were 8a.nu leaderboards and Mountain Project ticklists, before there were beta videos and newspaper articles for every cutting-edge ascent, there was a word-of-mouth understanding of who was setting the standard of the day.