This July, we look back at an accident in 2019. A climber took a serious lead fall while clipping the third bolt on a popular sport route in North Carolina called Chicken Bone (5.8). This climber made a fairly common error when his rope crossed behind his leg while climbing. This oversight resulted in serious injury from what should have been a routine fall.

Easy access and solid quartzite make North Carolina’s Pilot Mountain a popular destination. Photo: bobistraveling

FALL ON ROCK | Rope Behind Leg, No Helmet

North Carolina, Pilot Mountain State Park, The Parking Lot

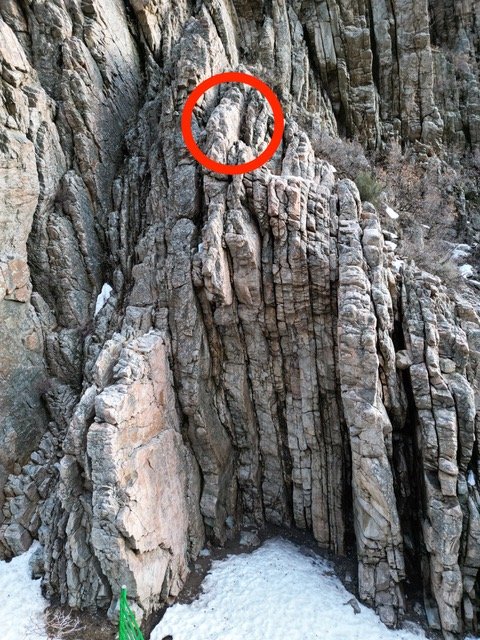

According to Mountain Project, Chicken Bone is an “awesome moderate and one of the longest routes at Pilot [Mountain].” The route has also seen several accidents in the last decade, including two serious falls at the third bolt (yellow circle). Ben Alexander

During the afternoon of May 6, Ranger J. Anderson received a call reporting a fallen climber. When Anderson found the patient, Matthew Starkey, he was walking out, holding a shirt on the right side of his head and covered in blood. However, he was conscious and alert. After ensuring the patient’s condition did not worsen, Anderson accompanied him on the hike. Medical assessment revealed a two-to three-inch laceration on the right side of his skull and light rope burns on his leg.

Starkey explained to rescuers that he had been lead climbing outdoors for his first time on the route Chicken Bone (5.8 sport). As he was nearing the third bolt, he lost his grip on a hold and fell. His rope was behind his leg, and this caused him to flip upside down and hit his head on a ledge below. Starkey said he was unsure, but felt like he had “blacked out.” He was not wearing a helmet.

(Source: Incident Report from Pilot Mountain State Park.)

Video Analysis—Rope Behind Leg

Many of us have fallen and had the rope catch behind our leg. Usually, we get nothing more than a bad rope burn. Unfortunately, there can be severe consequences if we get a hard catch, flip upside down, and strike our head.

Pete Takeda, Editor of Accidents in North American Climbing, is back with some advice on how to fall correctly.

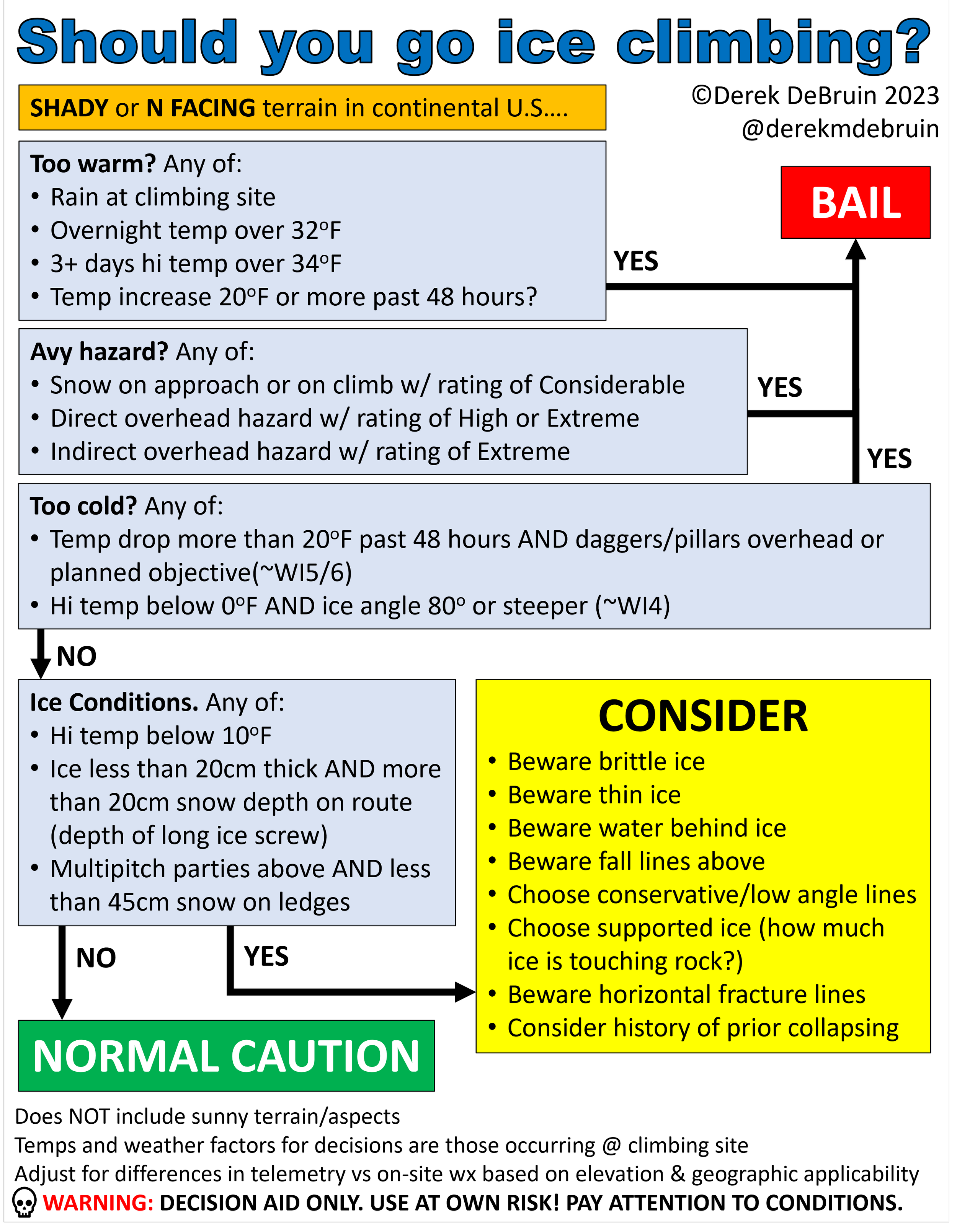

Pete Takeda, Editor of Accidents in North American Climbing; Katie Ferguson, Executive Assistant; Producers: Shane Johnson and Sierra McGivney; Videographer: Foster Denney; Editor: Sierra McGivney. Location: Canal Zone, Clear Creek Canyon, CO.

ANALYSIS

Avoid getting your feet and legs between the rock and the rope. A fall in this position may result in the leg snagging the rope and flipping the climber upside down.

While many sport leaders pass on wearing a helmet, this accident is a good example of its usefulness. Leading easier climbs can increase the risk for injury, as they often tend to be lower angle and/or have ledges that a falling climber could hit. (Source: The Editors.)

Editor’s Note: This was Starkey’s first outdoor climbing lead, and his lack of experience perhaps contributed to the accident.

Chicken Bone has been the scene of multiple accidents, mostly involving inexperienced climbers. Here are two more examples:

2021 | Fatal Fall From Anchor — Inexperience at Cleaning

North Carolina, Pilot Mountain State Park, Parking Lot Area

2018 | Ground Fall – Inexperience, Inadequate Belay

North Carolina, Pilot Mountain State Park, Parking Lot Area

Lead climbing carries inherent dangers regardless of the grade and amount of protection. Popular moderates might be more perilous than notoriously dangerous routes, as climbers can be more easily caught unawares on “easy” and well-protected terrain.