We are approaching the prime season for El Potrero Chico in northern Mexico. This month’s incident took place earlier this year on one of the most sought-after routes in this sport climbing paradise. The classic Time Wave Zero is perhaps the second-longest sport route in North America.

Belay Failure From Above

El Potrero Chico, Nuevo León, Mexico

Time Wave Zero, which climbs the buttress and headwall on the left side of this formation, is over 2,000 feet long and has a fully bolted crux that can be easily aided. These two factors make it a relatively popular route. Photo: Tony Bubb

“On March 14, 2023, my friend (the belayer) and I (Liu Yuezhang, 26) headed to Time Wave Zero (2,000’, III 5.12a or 5.11 A0) in El Potrero Chico (EPC) to check out the approach and prepare for a full attempt a few days later. Our plan was to try the moves of the first two pitches before returning to the ground. While following the second pitch (95’, 5.11b, nine bolts), I experienced a belay failure from above, hitting my right lower back, head, and both elbows as I fell. I was rescued by the EPC rescue team and local climbers. Miraculously, I was not seriously injured.

We had reached the crag around noon. It was drizzling, so there were not many climbers heading out. We were glad to meet two female climbers at an area close to Time Wave. They eventually performed the rescue. I led the first pitch (100’, 5.7, four bolts) and belayed my friend up. We switched leads and my friend led the second pitch, set up the belay, and notified me to follow.

My partner was belaying in guide mode off the bolted anchor (see Fig. 1). He double-checked the system by pulling on the climber’s side of the rope. I climbed to the eighth bolt. Earlier, I had noted that the crux was between the eighth and ninth bolt, so I decided to check out the moves. I said, "Take." I was on the rope around five to ten seconds when I suddenly began to free-fall. I remember the sky moving further and further away, so I must have been falling face up, with my back downward. I thought I was going die.

The belayer remembers releasing both hands at one point, after which the climber’s side of rope began to run rapidly through the ATC. In a panic, he attempted to hold the climber’s side, rather than the belayer’s side of the rope. His right hand got seriously burned. Eventually, the rope (9.5mm, 70m, almost new) stuck inside the belay device (Black Diamond ATC Guide, with Black Diamond RockLock screwgate carabiner) and I was stopped in a slabby area, around ten feet below the pitch 1 anchor. The falling distance was around 60–85 feet.

From my injuries, I inferred that I hit my lower right back on a bulge first, then struck the back side of my head and both elbows before sliding down the slab. My neck and tongue were also slightly impaired by the impact. Due to amnesia, I could not recall some details of the fall. I was wearing a helmet, backpack, and long-sleeve jacket. I noticed climbers approaching on the ground to provide help. Then, in what seemed to be the next second, they were above, readying to lower me. According to the belayer, I repeatedly asked “Where am I?” and said “Record the accident scene.”

The belayer spent around ten minutes trying to feed slack efficiently after I was connected to the rescuer, but I also did not recall this. My consciousness came back to normal while being lowered, but I still experienced some long-term memory loss. The rescue team performed a rapid response, and I was carried on a stretcher to an ambulance. This took around 30 minutes. I was sent to the emergency room in Monterrey and luckily was not seriously injured. I would like to express my utmost gratitude to the EPC rescue team and local climbers for the speedy rescue, especially Juliet. She was one of the female climbers we met earlier, who re-led the first pitch and lowered me down.”

—Liu Yuezhang

ANALYSIS

Yuezhang wrote:

“There were a few mistakes made. One error was when the belayer released both hands while belaying from above. This should be strictly prohibited even with an [assisted-braking] system. Also, the fall could have been caught if he had pulled the correct (belayer’s) side of the rope.

“Besides the above two obvious errors, we next tried to analyze the cause of the autoblock system failure. The ATC setting from the accident is shown in Fig. 1” (below).

Fig. 1 This is a screenshot of the actual anchor and belay configuration immediately following the accident. Photo: Courtesy of Liu Yuezhang

Yuezhang added:

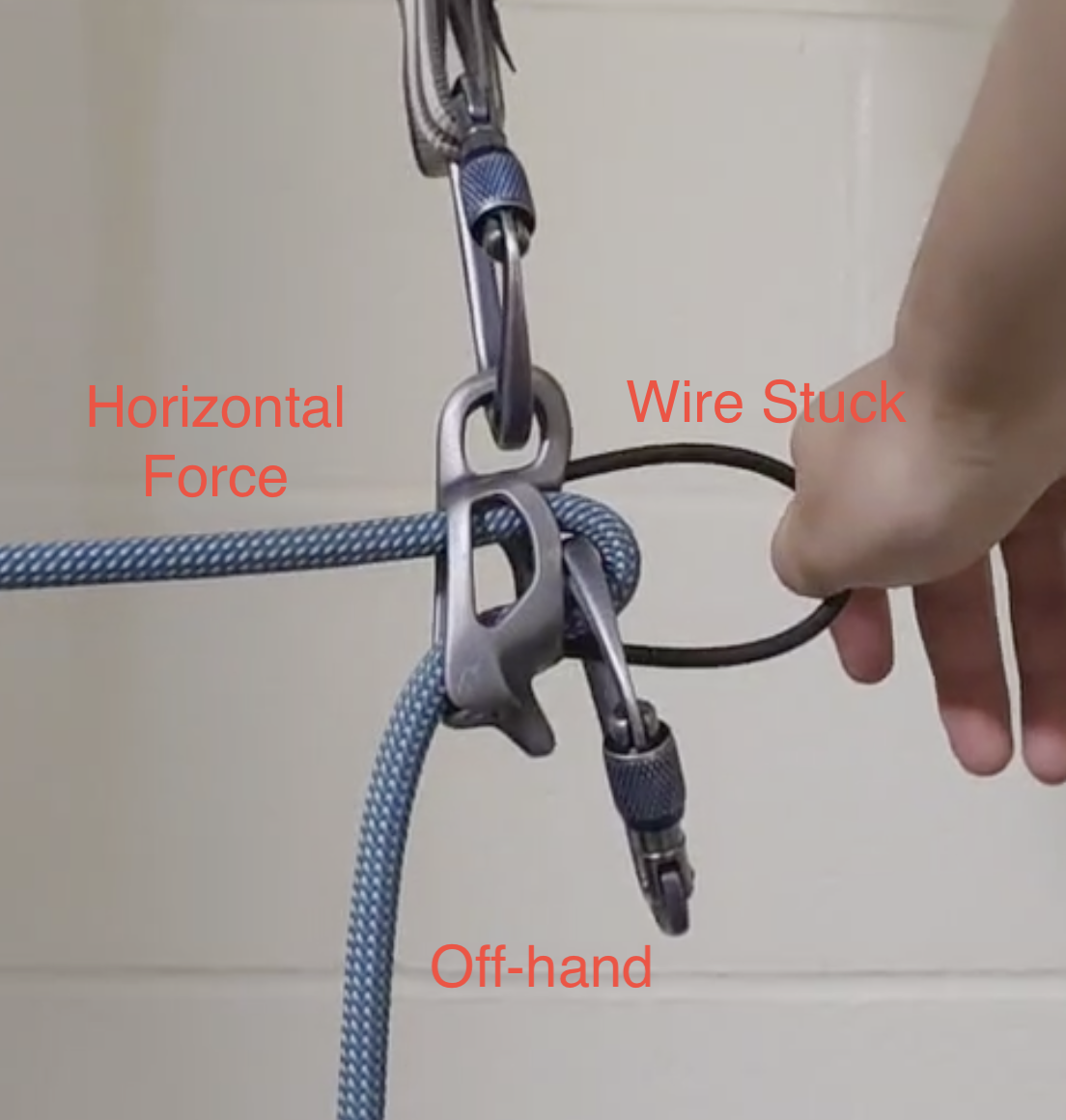

“From the photo, we can confirm that the ATC was set correctly (left strand is the belayer side and right strand is the climber side). The climber’s side was initially on top, and eventually got stuck beside the belayer’s side due to the falling impact. After some experiments, we found that the autoblock system might fail if (i) there was a horizontal component force pulling outward, since the belay station was above a bulge, and (ii) the wire of the ATC was stuck by something on the cliff. A repeat experiment is shown in Fig 2 (below). Again, this scenario is very unusual and can be avoided by always having a hand on the belayer’s side.”

Fig. 2 This shows how the ATC orientation can potentially allow the rope to run through the device in guide-mode. Photo: Liu Yuezhang

Yuezhang concludes:

“I was the more experienced climber in the team (one year of trad, multiple years of ice and sport climbing) and received training in multi-pitch climbing from an IFMGA guide. The belayer was the stronger, but less experienced, sport/gym climber. He had no experience of multi-pitch climbing before the trip. To compensate the experience difference, we held two educational sessions in a gym and completed two multi-pitch routes together. At EPC, we climbed several multi-pitch routes while safely switching leads. I emphasized the importance of keeping a hand on the belay side of the rope, even while in autoblock mode. Due to the limited experience with the ATC Guide, the belayer failed to react properly. Also, always wear a helmet. Mine saved me from more severe injuries.”(Source: Liu Yuezhang)

Editor’s Note:

It is possible that when Yuezhang called “take,” the belayer may have grabbed the bight carabiner (or the ATC retaining wire) to disengage the rope/carabiner/device in order to more easily take up slack through the device. While this is not recommended by the manufacturer, it is not an uncommon technique. Yuezhang recalls, “If my memory serves me, the belayer told me he first pulled the slack when I called ‘take.’” Thus, it is plausible that the belayer, finding it difficult to pull in slack, disengaged the rope. When the bight carabiner or retaining wire is pulled upward, it also orients the rope perpendicular to the top of the ATC (as shown in Fig. 2 above). In this case, the ATC might have been pulled horizontally. If the belayer did just that, while Yuezhang momentarily shifted his weight on and off the rope, the rope could have begun to slip rapidly through the ATC (see Fig. 3 below).

We know that the belayer, now panicking, mistakenly grabbed the follower’s side of the rope in a vain attempt to arrest the fall. His grip may have prevented the device from loading, that is, until excruciating rope burns forced him to release the rope. At this point, the rope locked in the now loaded ATC. The newness of the rope also probably played a role in the accident. Note that in the video below and in Fig. 1, the climber side of the rope is loaded adjacent to the brake side, not on top, as per the intended design. This is probably due to force of the fall and the slickness/diameter of the fresh rope. Extra caution must be taken with any braking or belay device when using a thin and slick rope.

Fig. 3 If the bight carabiner or retaining wire of the device is caught or held upward, and the climber’s side rope is loaded while perpendicular to the top of the ATC, the device can fail to catch. Video: Liu Yuezhang

Join the Club—United We Climb.

Get Accidents Sent to You Annually

Partner-level members receive the Accidents in North American Climbing book every year. Detailing the most noteworthy climbing and skiing accidents each year, climbers, rangers, rescue professionals, and editors analyze what went wrong, so you can learn from others’ mistakes.

Rescue & Medical Expense Coverage

Climbing can be a risky pursuit, but one worth the price of admission. Partner-level members receive $7,500 in rescue services and $5,000 in emergency medical expense coverage. Looking for deeper coverage? Sign up for the Leader level and receive $300k in rescue services.