In 2024, Maurice Chen and editor Dougald McDonald, worked together to produce Chinese translation of Accidents in North American Climbing. Allowing accident analysis to be more widespread.

All Aspects

The AAC DC Chapter hosts a New Ice Climber Weekend in the Adirondacks with Escala

PC: Colt Bradley

Grassroots: Unearthing the Future of Climbing

By: Sierra McGivney

The sun peeked over the Pitchoff Quarry crag, hitting the ice and creating an enchanting aura. The cool February air was saturated with people laughing and ice tools scraping against the ice. If you listened closely, you'd notice that the conversations were a beautiful mix of English and Spanish.

PC: Colt Bradley

The New Ice Climber Weekend (NICW), hosted by the AAC DC Chapter, has become an annual event. Piotr Andrzejczak, the AAC DC chapter chair and organizer of the New Ice Climber Weekend, believes mentorship is paramount in climbing. The weekend aims to provide participants with an opportunity to try ice climbing, find ice climbing partners, and have a starting point for more significant objectives. Above all, it aims to minimize the barrier to entry for ice climbing.

Last year, Andrzejczak approached Melissa Rojas, the co-founder of Escala and volunteer with the DC Chapter, about partnering to do a New Ice Climber Weekend with Escala. Escala is part of the American Alpine Club's Affiliate Support Network, which provides emerging affinity groups with resources in order to minimize barriers in their operations and serving their community. Escala “creates accessibility, expands representation, and increases visibility in climbing for Hispanic and Latine individuals by building community, sharing culture, and mentoring one another.”

Climbing can be a challenging sport to get into. It can require shoes, a harness, a gym membership, and climbing partners. Ice climbing requires all that plus more: ice tools, crampons, and winter clothing.

"There's a lot more complexity to ice climbing," said Rojas.

PC: Colt Bradley

Ice climbing can be limited not only in quantity but also in quality. Due to climate change, the ice in the Adirondacks loses its quality faster than previous decades and the climbs are only of good quality for a limited amount of time. DC climbers are at least seven hours from the Adirondacks, plus traffic and stops, so ice climbing for them has unforeseen logistical challenges. During the NICW, participants can focus more on the basics of learning to ice climb and less on logistics.

Rojas and Andrzejczak hosted a pre-meetup/virtual session so that participants could get to know each other and ask questions ahead of time. "We wanted to give folks an opportunity to ice climb in a supportive environment where they felt like they were in a community and were being supported throughout the whole process, from the planning stage to the actual trip," said Rojas.

Another focus of the weekend was creating a film. Colt Bradley attended the New Ice Climber Weekend in 2023 as a videographer and as a participant. Bradley volunteers with the AAC Baltimore Chapter and is also Andrzejczak's climbing partner. Last year, he created four Instagram videos that captured the excitement of ice climbing for the first time. When asked to film the Escala x NICW this year, he wanted to do something longer and more story-focused. Bradley and Rojas talked beforehand about focusing the film on the Escala community and highlighting the bond made possible through its existence.

Rojas has worked hard to build up this blended community of Spanish-speaking climbers. Spanish has many flavors, as it is spoken in many different countries with different cultures—all unique in their own way. The film focused on reflecting and representing the vibrant community of Escala.

Soon, they all found themselves at Pitchoff Quarry in the Adirondacks. While the participants learned how to swing their ice tools and kick their crampons into the ice, Bradley sought out community moments. He wanted to put viewers in the moment as participants climbed, so he mic'd some participants; including Kathya Meza.

Meza spoke openly during interviews and had a compelling story that Bradley thought would resonate with the viewers.

PC: Colt Bradley

In the film's final scene, viewers can hear Meza swinging her tools into the ice, see her smiling, and experience her problem solving as she pushes herself outside her comfort zone. Bradley filmed this scene the first day before they even identified her as a focal point of the film.

Bradley continued to capture the essence of the Latino influence over the weekend. On the second day, the group headed to Chapel Pond. Despite the cold 21-degree weather and whipping wind, the energy was high. Mentors taught mentees how to layer correctly, and folks danced salsa at the base of the crag to stay warm. Later, feeling connected and energized from this incredible trip, the group salsa danced on the frozen Chapel Pond with the iconic ice falls that makeup Chounaird's Gully and Power Play in the background.

"For the twenty-some-odd years I've been going to the Adirondacks to ice climb, I've never even thought that maybe one day I'll be dancing on Chapel Pond, hosting a new Ice Climbing weekend with Escala" said Piotr.

For Rojas, it was some of her best salsa dancing. She was so focused on staying warm that it freed her from overthinking her dancing skills. The dancing didn't stop at Chapel Pond. After dinner, the group returned to the inn and fired up the woodstove in the recreation room. The sound of salsa dancing and glee filled the room.

The NICW isn't about going out and sending, so naturally, this isn't the type of climbing film where climbers try hard on overhung climbs overlaid with cool EDM music. Every climber remembers the moment they got hooked on climbing, whether sport, trad, ice, or alpine climbing; they remember the thrill of reaching the top of a climb for the first time, out of breath but more excited than ever. Climbing is a multifaceted sport, and climbing films should be reflective of that. Showing the first-time-swinging-an-ice-tool moments at the NICW inspires someone to take that first step toward something new or nostalgic for the longtime climber.

PC: Colt Bradley

"I think the thing about Escala is it's more than just a climbing group. It's a community," said Rojas.

Escala is a place where Rojas can be all parts of herself. Rojas has four children and refers to Escala as her fifth baby. She doesn't have to explain why she climbs or her love for Sábado Gigante–a famous variety show in Latin America. Everyone in her community recognizes all aspects of her. Her identity as a climber and as a Latina can be one.

One participant of the NICW approached Rojas and said it was the best experience of their life.

PC: Colt Bradley

"He said it with such sincerity that it was really humbling in the moment," said Rojas.

Leading an affinity group can often feel like running on a never-ending treadmill of organizing event after event, where reflection takes a backseat. However, according to Rojas if she can positively affect just one person, it makes all the work worth it.

Salsa music playing over Chapel Pond, smiling faces red from the winter frost, and dancing in crampons are the mosaic of moments that make up the heart of Escala, the DC Chapter, and the New Ice Climber Weekend.

Watch Escala En Hielo Below

The Foundation of Our Progress

Volunteer Spotlight: BIPOC Initiatives at AAC Twin Cities

by Rodel Querubin

PC: AAC member Rodel Querubin

One of our dedicated volunteers from the AAC Twin Cities Chapter, Rodel Querubin reflects on his incredible success in building an (ever growing) BIPOC climbing community there, as well as lessons learned from the process of growing his initiative. Querubin’s analysis of the intentional and thoughtful programming that the Twin Cities Chapter has rolled out over the last few years is an informative roadmap for the climbing world as we work toward being the most inclusive community we can be.

Mountain Goat Movement

An AAC member gives back to his community after receiving the Live Your Dream Grant.

PC: AAC Member Greg Morrisey

Grassroots: Unearthing the Future of Climbing

By: Sierra McGivney

There is nothing like watching the sunrise over the mountains, the whole world still sleeping. Pinks and deep oranges color the sky. On clear and quiet days, the temperature is coldest near or slightly after sunrise. Warm coffee, hot chocolate, or tea is always welcome during this time.

After years inside, these moments feel more special. All the lives lost and time stolen because of the pandemic make time spent outside invaluable to begin healing. At Mountain Goat Movement (MGM), explorers and teachers show students moments like these and the value of nature through outdoor adventures.

Morrisey speaking at the AAC’s Annual Benefit Gala in 2018.

For ten years, Greg Morrisey was a high school teacher at Saint Peter’s Preparatory in Jersey City, NJ. He spent the school year building an outdoor education program and the summer going on expeditions. In 2017 Morrisey won the American Alpine Club’s Live Your Dream Grant and completed an unsupported 1,800-mile cycling trip with one of his fellow teachers. In addition, that expedition raised $40,000 for low-income students to come on trips with Morrisey’s outdoor education program.

“That funded about 15 kids, and it was kind of crazy,” says Morrisey.

Morrisey was asked to speak at the AAC’s Annual Gala alongside Vanessa O'Brien that year. The grant changed his life.

In June of 2022, Morrisey quit teaching. He took the model he created at Saint Peter’s Preparatory and turned it into Mountain Goat Movement, a program that reaches out to schools primarily in populated cities or suburban areas in New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Maryland, to get students into the outdoors.

Two MGM participants in the Adirondacks, New York. PC: AAC Member Greg Morrisey

“It's easy in Colorado, Wyoming, and Upstate New York to just walk out your backyard, and go for a beautiful hike, but it's difficult in the greater New York City area so we're trying to rally a community to get in the outdoors and provide resources for anyone and everyone who wants to experience the beauty of nature,” says Morrisey.

After teaching during COVID-19, Morrisey realized how fractured life was for young people. Students have been on an island these past couple of years and reintegrating into school and society has been a shock to their system.

Like the true literature teacher he is, Morrisey explains that outdoor adventures are much like the hero’s tale in Western Literature. A young person goes out on an epic quest, leaving their comfort zone, to battle figurative monsters and demons and comes home transformed. Morrisey gives presentations at school about the mental health benefits that can be derived from spending time in nature. He compares it to the hero's journey: Wherever you are, high school or college, you are not that much different than the characters you are reading about.

A MGM group on the summit of Kilimanjaro.

Unlike Outward Bound or NOLS where participants rarely see their guides again, MGM brings the student’s teachers on the trip. The idea behind MGM is to build connections outdoors and be able to bring that back to the classroom instead of having a one-off trip. In addition, Morrisey hopes that this can also start a conversation about mental health in the classroom and how venturing into the outdoors can benefit mental health for people of all ages. Morrisey goes on every trip to train the student’s teachers with the hope that they can lead their own trips using this model.

“I think when you're on an expedition or a multi-day experience, and you break bread with people, share tents, hike, and do everything together, it's inevitable that you're going to become close,” says Morrisey. “So taking that experience and then coming back home and building off that is the most beautiful part of all this.”

PC: AAC Member Greg Morrisey

Students who might not have ever talked or met suddenly have bonded with one another and become lifelong friends.

Last July, Morrisey took a group to Kilimanjaro. His whole group summited and watched the sunrise from the top. Everyone cried. Evidently, the softer moments in the outdoors allow for meaningful relationships to form.

“It's been a very rewarding process of working with young people in the outdoors and teaching kids how to climb, hike, ski, and get outside,” says Morrisey.

Participants don’t have to travel out of the country to have these experiences. Mountain Goat Movement offers domestic trips like climbing the Grand Teton or hiking all 46 high peaks in the Adirondacks. They do also offer an extensive amount of international trips to Kilimajaro, Costa Rica, and the Himalayas.

The name behind MGM is intentional. Mountain goats are always trying to seek higher ground to survive. And just like mountain goats, whenever MGM takes participants outside, they try to achieve something higher within themselves while also respecting and protecting the land they tread on. Movement relates to being present outside, off your phone, and also moving as a community.

PC: AAC Member Greg Morrisey

The positive effects of this type of program are evident. Morrisey has seen participants who came up through his program become ice climbers, environmental scientists, and AAC members, but most of all more confident explorers and adventurers in the outdoors and in life.

“[the AAC] has always been super supportive and one of the reasons why we're able to start the foundation was because of the Live Your Dream grant, so I feel like the AAC has just done absolute wonders for a lot of kids in New York City without them actually realizing it,” says Morrisey.

He is excited to expand and watch MGM grow. John Barnhardt, a filmmaker known for the Amazon Prime TV Show Born to Explore is joining MGM. He will be documenting their experiences on all seven continents for the next year. Morrisey is looking forward to having him join the team and help get the word out.

PC: AAC Member Greg Morrisey

Just like mountain goats, we too can learn and adapt to our environment, mentally and physically. Movement in the outdoors has immense benefits. If you want to get involved or go on a trip with MGM visit their website here.

Inviting Communities In

The AAC Twin Cities Chapter partners with Spanish speaking communities to bring people climbing.

PC: AAC Twin Cities DEI Initiatives Chapter Chair Rodel Querubin

Grassroots: Unearthing the Future of Climbing

By: Sierra McGivney

As the leaves change, students flood classrooms, back to school for another semester. Students at El Colegio Highschool, a small charter school in South Minneapolis, always wondered why their teacher Steve Asencio was covered in bruises and cuts.

When the school bell rang Asencio was at his local climbing gym, hanging out with friends while bouldering and top-roping. Each time, he'd come away from the climbing wall with bruises and scrapes—practically a requirement for climbers.

Asencio found climbing through the BIPOC events put on by the AAC Twin Cities Chapter in 2021. The space for new learners and community grown by Rodel Querubin, the Twin Cities DEI Initiatives Chapter Chair, allowed Asencio to immerse himself in climbing. Asencio even applied for the AAC-TC BIPOC Ice Climbing Scholarship in 2021 and was able to attend Michigan Ice Fest to hone his skills further.

PC: AAC Twin Cities DEI Initiatives Chapter Chair Rodel Querubin

When Asencio saw an opportunity to bring his passion for climbing to the classroom he reached out to Querubin. Twice a year students at his school participate in an interim week in which the teachers design a three-hour-long class of their choice.

Ascencio emailed Querubin: do you think that we could create some sort of class and partnership to teach students how to climb? Querubin didn’t hesitate, Yes. He didn’t even know if he could make this happen or where funding would come from, but Querubin is committed to keeping as many doors open as possible in his work, so he decided he would find a way.

El Colegio is not your average high school. The school is a tuition-free charter school with a focus on community-building and social justice. The staff is fully bilingual and has been recognized locally and nationally as an innovative force in improving achievement for Latino students and other students of color. As Asencio talked to students about climbing he realized how inaccessible it was to them. Very few students had climbed before and if they had, they had only done so in their native countries.

“I felt like I was that student. I grew up in Atlanta, I didn't climb until I came to Minnesota and was 26 or 27 years old,” says Asencio.

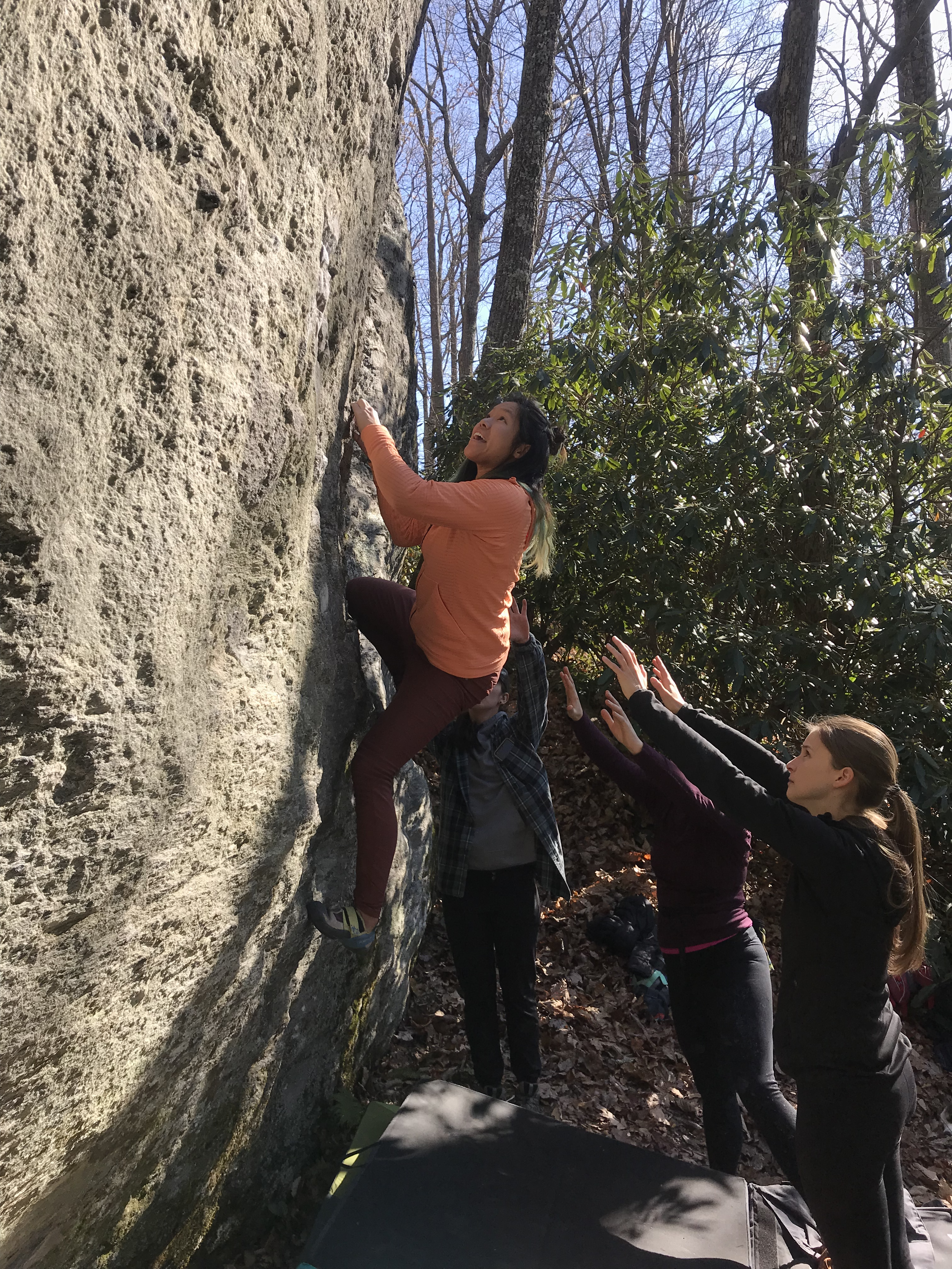

A student from El Colegio high school, climbing at Vertical Endevours. PC: AAC Twin Cities DEI Initiatives Chapter Chair Rodel Querubin

Giddy and scared, the kids tied in at Vertical Endeavors. Shouts of encouragement filled the gym as the kids pushed one another to climb. Asencio would watch a kid get stuck on a route and walk by thirty minutes later to the same kid finishing up.

“I think that, to me, was just super powerful as that can translate into life,” says Asencio.

Being able to complete something new after being scared of what lies on the other side is a huge accomplishment. A lot of the students at El Colegio are originally from countries such as Ecuador, Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. A few kids had only been to school, work, and home. They didn’t have the opportunity to go anywhere outside of those three settings. The students got to be in a space that is completely new while also being fulfilling, rewarding, and challenging.

“I was very impressed with [the students]. I think they kind of took on that challenge,” says Asencio.

Asencio’s goal has always been to expose the students to climbing with the hopes that they will, in turn, expose their family, friends, and others. This is how they begin to create a Spanish-speaking space within the climbing community.

PC: AAC Twin Cities DEI Initiatives Chapter Chair Rodel Querubin

News spread fast through the school that Mr. Asencio’s interim climbing class was cool. Asencio had kids running up to him exclaiming that they had to be in his class. The class has become one of the most popular and spots are limited. Asencio is always trying to see how he can get as many interested kids on the wall. In the second semester, Asencio had a few returning students who helped teach the new kids the ropes.

“Most inspiring and touching to me was that two of the students who had participated during our first events in October of last year returned for this latest round and were able to teach the rest of their class how to belay instead of me—in Spanish,” says Querubin.

Luisana Mendez the founder of Huellas Latinas, a hiking club based in Minnesota oriented toward Spanish-speaking individuals, found climbing in the same way Asencio did, through the events that Querubin hosted. She approached Querubin about a partnership to take participants in the hiking club, climbing. Although Huellas Latinas is primarily a hiking club, being outdoors is what brings everyone together, no matter the activity.

Huellas Latinas gearing up to climb. PC: AAC Twin Cities DEI Initiatives Chapter Chair Rodel Querubin

At the time Querubin didn’t have a framework or funding for an event. After the success of the climbing event at El Colegio highschool, Querubin reached back out to Luisana Mendez to restart the conversation about hosting an event alongside Huellas Latinas.

“I feel like those types of communities are the exact spaces where we want to be expanding the reach of climbing and the possibility of it—folks who are already interested in the outdoors but maybe don’t see themselves in climbing or just aren’t aware of the resources to them,” says Querubin. “Any number of things that we take for granted as far as access to climbing, [we can address those obstacles.] I want to make sure that those communities see that those opportunities are available.”

PC: AAC Twin Cities DEI Initiatives Chapter Chair Rodel Querubin

They hosted two different events, one rope climbing, and one bouldering. Participants loved it. Everyone was enthusiastic about the opportunity to try something they wouldn't necessarily see themselves doing.

If participants decided they enjoy climbing after the event, they could attend the weekly BIPOC climbing events put on by the AAC Twin Cities Chapter.

“We’ve been seeing some of those folks join in on BIPOC events, so that was the beauty of that, not just having these one-off events but then the ability for them to join in on our more regularly scheduled events,” says Rodel.

Everyone loves a good party. Big events like Craggin’ Classics and Flash Foxy draw in all types of climbers, who get to socialize and celebrate climbing. The issue is, what happens to those climbers who got introduced to climbing at the big event? What support network is in place to allow them to continue climbing and form the community needed in order to continue their climbing career? Running smaller, more frequent events, like the AAC Twin Cities Chapter is able to do, allows a community to build organically and supports the folks who are pulled in by exciting one-off events.

Working with Huellas Latinas and El Colegio has been part of a bigger push to partner with other groups and organizations to bring them into climbing. In 2020, the pandemic in conjunction with the murder of George Floyd made Querubin, his fellow members, and the leadership team at the Twin Cities Chapter reevaluate what they wanted their priorities to focus on. They took some time to focus on how best to address systemic racism, inequities, and the imbalance of access. Phase one: Create a space for BIPOC communities through gym partnerships and events.

PC: AAC Twin Cities DEI Initiatives Chapter Chair Rodel Querubin

“When you take a step back there are very specific responsibilities and intentionality when you run BIPOC spaces. Or at least there should be. And so what that means is not just having these events, but also making some very specific and intentional invites to communities and relationship building,” says Querubin.

Phase two was to invite communities to get involved and be represented in the climbing community. Part of the purpose of introducing climbing to groups that had already built a community, like students from El Colegio high school and participants of Huellas Latinas, was to ensure the individuals participating felt safe and welcomed through a partnership they already trusted. After the events, participants had the opportunity to advance in climbing if they were interested in doing so with the AAC Twin Cities Chapter.

“I wanted to start up this program, which was to help communities so that we aren’t gatekeeping that knowledge, where we’re empowering their community and to then have leaders in their communities,” says Querubin.

PC: AAC Twin Cities DEI Initiatives Chapter Chair Rodel Querubin

No Longer an Old Boys’ Club

The AAC Triangle Chapter nourishes a strong female climbing community.

PC: AAC member Anne McLaughlin

Grassroots: Unearthering the Future of Climbing

By Sierra McGivney

A woman's place is on lead. No longer is climbing “an old boys’ club.” This is true now more than ever. The future of climbing is expanding beyond traditions of the past at a rapid pace.

In North Carolina, AAC member Anne McLaughlin created a network of women climbers aiming to empower those who identify as female. What started as a Women's Climbing Night evolved into a network of women aged 20-70 who are all bound together by their love of climbing.

“We called ourselves women’s climbing night until this year. We realized we were more than a night, we were a network,” says McLaughlin.

McLaughlin yearned for a women’s climbing community in North Carolina. Although North Carolina has a strong climbing community, there was not a strong female presence.

PC: AAC member Anne McLaughlin

Oftentimes women are introduced to climbing by male partners or friends. Although there is nothing inherently wrong with this, it does reflect the reality that the majority of educators, mentors, and guides are men, positions that allow for knowledge-sharing and decision-making that shape the culture of climbing. In addition, because of societal pressures, someone who identifies as a woman may feel as though they have to prove themselves in front of a male climbing partner. When women climb with other women that pressure can often disappear, and they can focus on the climb at hand.

Jane Harrison, a friend of McLaughlin’s had run a women’s climbing meet-up when she was living in Oregon. She approached McLaughlin about starting one in the area. Together they began to devise a plan to create a Women’s Climbing Night for their local North Carolina community.

The key was to keep the event casual and have a core group of women who attend, organize, and facilitate. Instead of having a one-off event, they opted to have a consistent two nights a month blocked off for women’s climbing. Establishing rapport and consistency with their community encourages participants to have a long-term relationship with climbing. Harrison and McLaughlin began hosting meetups at their local gym, Triangle Rock Club in January of 2018.

“Ever since then, we've just had more and more people joining up,” says McLaughlin. “Right now I run the email list and we have over 260 women.”

PC: AAC member Anne McLaughlin

Cory Johnson, the AAC Triangle Chapter Co-chair, got involved quickly with the Women’s Climbing Network (WCN). She discussed with McLaughlin how the AAC could partner with them. Now, the AAC Triangle Chapter supports the WCN by providing access to their gear closet for outdoor events and promotes them on the Triangle Facebook page. Johnson encourages women who attend the Triangle Chapter skills clinics to get connected with McLaughlin.

“So many of the women who've joined our group came to it through taking a clinic through the American Alpine Club Triangle Chapter,” says McLaughlin.

In the North Carolina climbing community, there is a strong desire to find good consistent partnerships and mentors. By creating a strong women’s climbing community that removes hurdles like gym to crag transition, McLaughlin has provided a safe climbing environment that empowers women.

“There is a hunger out there for women to climb with other women and learn from other women,” says McLaughlin.

PC: AAC member Anne McLaughlin

McLaughlin wasn’t always the strong trad crusher she is today. Her first time climbing left her disappointed and discouraged. At the time she was a graduate student at Georgia Tech and had signed up for a beginner outdoor climbing class. No prerequisite needed. The group piled into a van and drove out to Sand Rock, Alabama, a crag that McLaughlin would come to know well over the subsequent years. Sand Rock is known for its beginner-friendly toprope jug routes —full of horns, suitcase handles, and chicken heads—as well as crimpy face climbs and thin crack lines. Sport routes run parallel to difficult trad routes. There are even a couple of good bouldering problems—some even describe it as "the Southeast's most underrated bouldering area,” according to Mountain Project.

McLaughlin was the only woman in the group on her first trip. The guides set up one of the notorious overhung juggy 5.6 climbs. The moves resembled a pull-up. Each tug upward makes the climber look and feel strong, while being a relatively easy route. But it was not “easy” for McLaughlin. She stood at the base, trying repeatedly to pull herself up with no success. She thought: I’m worse than everyone here. I’m failing. I’m just not a climber.

Around the corner was a multitude of slab routes. Routes that might have favored McLaughlin's strengths. But McLaughlin had only been presented with one version of what climbing could be.

PC: Adriel Tomek

“Having that experience, [you realize] you have to set up people for success and play to people's strengths,” says McLaughlin. “Observe what they can do and what they are having trouble with, and tweak their opportunities to ensure they have an excellent first experience, especially outside.”

A couple of years later during an internship in Florida, McLaughlin tried climbing again. Her supervisor, Gwen Campbell, was a climber in her 50s and brought her to the local climbing gym in Orlando. Campbell was McLaughlin's biggest cheerleader. Every move McLaughlin made was followed by a cheer and shout of excitement.

“She introduced me to climbing and I absolutely loved it,” says McLaughlin.

Now, McLaughlin is the cheerleader. Although education is not the point of their trips, McLaughlin gives participants an opportunity to learn. She spends the day showing anyone interested how to clean sport routes, rappel, and flake the rope. One woman, Rachel, who is primarily a gym climber, began going to their outdoor events. McLaughlin anchored into the top of a climb at Pilot Mountain while Rachel cleaned the anchor. The sun beat down on the two of them as Rachel cleaned the anchor first with McLaughlin’s instruction and then with McLaughlin just watching to make sure she was safe.

Later McLaughlin received an email from her, explaining that she had practiced cleaning the anchor and was able to take her friends out and teach them. She had felt empowered by McLaughlin's instruction and was grateful.

“That made my day,” McLaughlin says with a smile.

PC: AAC member Anne McLaughlin

The goal of the WCN is to connect and empower women, arming them with knowledge so they can advocate for the climbing they want to do, and make informed and safe decisions for themselves in the mountains. Participants are encouraged to find climbing partners and friends to meet up with outside of WCN nights and events. Independence within climbing allows women to make decisions in the mountains confidently, a skill every climber should have. The network provides an environment for women of all ages to grow, learn, and connect.

“If you see it, you can be it,” says McLaughlin.

Education in the Face of Grief

The AAC Triangle Chapter offers education clinics at the North Carolina Climbing Fest.

PC: AAC Triangle Chapter Co-Chair John White

Grassroots: Unearthing the Future of Climbing

By Sierra McGivney

When tragedy struck the North Carolina climbing community after a fatal rappelling accident in 2012, the AAC Triangle Chapter decided to turn its focus to education. David Thoenen and Danny McCracken, former volunteer leaders for the AAC Southern Appalachia and Triangle Chapters, created a best practice climbing education initiative for their chapter. The current co-chairs of the Triangle Chapter, Cory Johnson and John White, are carrying the torch with a strong drive to educate climbers.

“Part of how [previous Triangle Chapter Chairs] wanted to address their grief was to give back to the community and try to provide rappelling best practices,” says Johnson.

They created clinic guidelines based on the AAC: Know the Ropes and videos from the AMGA website explaining each topic. Clinics like “Rappelling,” “Two-Bolt Anchors: The Quad,” “Two-bolt Anchors: Cleaning and Lowering,” “Belaying From Above,” and “Knots For Climbers,” are all offered.

PC: AAC Triangle Chapter Co-Chair Cory Johnson

The AAC Triangle Chapter hosts these climbing clinics weekly at various Triangle Rock Club Gyms. The clinics are free and open to anyone who pays for a membership or day pass to the Triangle Rock Climbing Gym. North Carolina climbers looking to elevate or refresh their knowledge can visit their website.

“Our general philosophy with all of our clinics is to make sure everyone can continue enjoying these resources and everyone has the tools to climb safely,” says Johnson.

In addition, the Triangle Chapter members and volunteers attend different festivals and events to offer clinics to all levels of climbers. When Bryce Mahoney, an AAC member and board member of the Carolina Climbers Coalition, reached out to Johnson and White about the Triangle Chapter hosting clinics at the North Carolina Climbers Fest (NCCF), they jumped on the opportunity. Johnson headed the project, organizing four clinics hosted by herself and other AAC volunteers at the festival, instilling confidence and knowledge in climbers.

Practice rings and tree anchors decorate the Jomeokee Campground in Pinnacle, NC on Saturday, May 14th. The AAC Triangle Chapter volunteers taught clinics to participants of the North Carolina Climbing Fest. Dirty hands worked together to carry rocks, building trails around the climbing areas of Pilot Mountain, just five miles from the campground. Climbers and hikers enjoyed a pancake breakfast cooked by Mahoney, the owner of the Jameokee campground and host of the NCCF, to fuel before the day's activities.

“I just love bringing people together,” says Mahoney.

A volunteer teaches a group of participants. PC: AAC Triangle Chapter Co-Chair Cory Johnson

Mahoney began his climbing career at Pilot Mountain when a friend opened his eyes to the world of climbing. Rock climbing and volunteer trail work with the Carolina Climbing Coalition became an outlet for him. At the time, Mahoney was working as a Virtual Veteran Support Specialist, a counselor offering peer support, crisis management, and VA resource navigation to promote quality of life and well-being for Veterans and their family members.

“While I was doing the veteran support work, there were not a lot of victories the day of, so being able to go somewhere and use my physical abilities to do something was awesome,” says Mahoney.

Mahoney had a background in construction, so building trails outdoors, in a place he loved, was rewarding. Volunteering at the CCC wasn’t enough for Mahoney so he joined the C4 team, a group of individuals that create and improve climbing access in the Carolinas, but he yearned to be on the board of directors. Two weeks later a seat opened up, and Mahoney eagerly joined. Now, Mahoney owns his own rock climbing guiding company: Yadkin Valley Adventure.

When Mahoney attended the South Carolina Climbing Fest he thought to himself, we need a festival like this in North Carolina. But not long after, COVID-19 hit and stopped all events. This year, with the reopening of restaurants, offices, and events, Mahoney put on the North Carolina Climbers Fest.

PC: AAC Triangle Chapter Co-Chair Cory Johnson

Teaching and facilitating clinics even for a small group of people makes a huge difference in Mahoney’s eyes. Everyone makes mistakes in the mountains. Recognizing those mistakes, implementing best practices, and refreshing safety knowledge help us become better climbers. Success to Mahoney is knowing that these climbers leave with more knowledge in critical safety skills than they arrived with.

“I do feel responsible as a professional rock climbing instructor, board representative, and a representative of this community in this region to stand out there and be like, we need to make sure we're double-checking these things, preventing injuries and deaths,” says Mahoney. The alliance between Mahoney and the AAC Triangle Chapter, with their focus on climber education, was a natural fit.

Next year you won’t see the North Carolina Climbing Fest but the North Carolina Outdoor Fest. A strong climbing presence will remain at the festival. Mahoney aims to be more inclusive in the small, tight-knit outdoor community in North Carolina. Most people that climb also mountain bike, kayak, hike or recreate in the outdoors in another way.

“I see more communities being here,” says Mahoney.

PC: AAC Triangle Chapter Co-Chair Cory Johnson

A strong climbing education presence will still be a part of the festival. If you're looking to connect, learn, or simply want to have fun in the outdoor community, this festival is for you. In the meantime attend a clinic or get involved within your local AAC Chapter. Members like Mahoney, Johnson, and White drive the AAC’s work at the grassroots level to equip climbers with the necessary knowledge to be safe and successful in the mountains.

*Danny McCracken passed away this past fall. We are grateful for the impact he had on the Club.

Build-A-Crag

The Western Michigan AAC Chapter partners with the Grand Rapids Bouldering Project to build an Outdoor Bouldering wall.

PC: AAC member Charlie Hall

Grassroots: Unearthing the Future of Climbing

By Sierra McGivney

Towering rock climbing cliffs, or even boulders, are hard to come by in Western Michigan. But if you can’t go to the rock, make the rock come to you.

Charlie Hall and Kyle Heys did just that by building an outdoor bouldering wall in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Inspiration came from climbing farther out West and seeing man-made boulders in public parks. Heys had always thought it was funny since these places had real rocks to climb, minutes outside of town.

“We thought, man, this is what we need in the Midwest, where it takes six hours to drive to good rock,” says Heys.

Kyle Heys was introduced to rock climbing in New Mexico in a semester away program through his college; he continued his climbing adventure by exploring Grand Teton National Park that summer with a band of climbers.

Once he returned home to Michigan his climbing lifestyle slowed. He didn’t want to pay for an expensive gym membership. Luckily his neighbor had a climbing wall in his garage, feeding his climbing addiction.

PC: AAC member Charlie Hall

When attending college at Western Michigan University, Charlie Hall saw a class labeled rock climbing and decided to take a chance. The two instructors at the recreation center wall nourished Hall's love for climbing.

“I idolized them a little bit and quickly realized that they were these supernatural beings who could scale a wall.” Says Hall, “I was fascinated by it.”

Everything revolved around climbing after that.

PC: Zane Paksi

Hall and Heys started the Grand Rapids Boulder Project five years ago with hopes of diversifying climbing through accessibility. The bouldering wall eliminates almost all barriers to climbing. Participants don’t have to pay for a membership or a day pass to a gym. The wall is open to all.

Through word of mouth, they hope to get more recognition for the sport in a less outdoor-centric area. Another goal is to facilitate programs for kids who wouldn't normally get access to climbing.

“How do we create something where anybody can get a chance to get an introduction to climbing?” says Heys.

Hall and Heys needed a fiduciary so they got connected with the Western Michigan AAC Chapter. It was synergistic. The Western Michigan AAC Chapter was growing and looking to foster a community around climbing but didn't have a concrete project. Heys and Halls provided just that.

To raise money for plastic holds, the AAC and the Grand Rapids Bouldering Project fundraised through the No Man's Land Film Festival. This doubled as a chance to provide a broader picture of what it means to be an outdoor adventurer to those not within the climbing community. Sponsorships and donations, whether that be time or money, have been the foundation of the Grand Rapids Bouldering Project.

The Grand Rapid City Park funded a majority of the materials to build the project and helped walk the pair through building an outdoor bouldering wall. When building within a city, there are lots of restrictions and requirements that need to be met. Williams Marks, an engineering firm, donated their time to help get the project approved by the city. Private and public partnerships worked together to make this project possible.

The Grand Rapids Bouldering Project took off in the fall of 2021, and building began this spring. Hall, Heys, and their crew of 5-10 volunteers thought their spring days would be idyllic. It has not been above 40 degrees on any of the building days. That hasn’t stopped the excitement.

“It's been a real, old fashion Amish barn raising.” says Heys with a laugh, “People all lifting the walls together. It's been great fun.”

The bouldering wall nods toward old-school climbing gyms made out of plywood and two-by-fours. The structure is meant to be a test site to see if people from all different communities use it. Down the road, the wall could evolve or grow into something bigger, possibly a wall crafted out of fake rock material, tied to the landscape.

PC: Zane Paksi

Two 12-foot-high free-standing structures sit next to each other surrounded by twelve inches of tumbled wood chips waiting to soften climbers' falls.

Overhangs, slabs, and vertical walls are all featured on the bouldering wall. All of the holds will be put on the wall to start out. Problems will be rotated based on consistency and quality of routes. The difficulty will be determined by colors: purple, blue, green, and red. A dedicated crew of local setters will set regularly. They have access to a storage unit on-site at the park. On their website, Grand Rapids Boulder Project has a spreadsheet that they plan on using to communicate what's up on the wall.

PC: AAC member Charlie Hall

Grassroots work has brought this project to life. The soft launch of the Grand Rapids bouldering wall will take place in Mid June once the wall has been painted and holds have been mounted. Hall and Heys will host a grand opening on July 9 with a climbing competition, food, and music.

“We have the ability to network and provide accessible climbing to the community,” says Hall.

A Gateway to Ice Climbing

The AAC DC Chapter hosts a New Ice Climber Weekend in the Adirondacks

PC: AAC member Ben Garza, https://www.bengarza.media/

Grassroots: Unearthing the Future of Climbing

By Sierra McGivney

“How would you describe the ice in the Adirondacks?”

“Delicious!” says Piotr Andrzejczak, the Washington D.C. AAC Chapter Chair.

PC: AAC member Ben Garza

The American Alpine Club Washington D.C. Chapter hosted the New Ice Climber Weekend on February 26 & 27. In collaboration with the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club and Arc’teryx, the event was held in the Adirondacks. On a good day, the drive is around seven or eight hours to the 6.1 million-acre park in Upstate New York.

Ice in the Adirondacks is consistent. Even if there is a warm spell or a rainy day, the ice always heals and survives late into spring. Anything closer to Virginia is unpredictable. Ice routes that were once flowing over cliffsides can disappear in days. Unlike rock routes, ice changes constantly.

“It can be brittle, scary, and intimidating or it can be cruise control,” says Andrezejczak.

PC: AAC member Ben Garza

When the group of ten participants arrived on Friday, months-old brown leaves were on the ground, but the ice was still in. Overnight the Adirondacks got about a foot of snow and transformed into a winter wonderland. On Saturday, rays of sunshine hit pillars of fat ice in Cascade Pass. Climbers donned sunscreen and sunglasses to protect themselves from getting burnt.

The energy was high. Everyone wanted to learn. Participants got first-hand knowledge on placing ice screws, climbing techniques, and building V-Threads.

The weekend exposed experienced rock climbers to a new discipline. Unlike going climbing with a guide, the New Ice Climber Weekend offered mentorship and promoted members finding ice climbing partners. Seneca Rocks Climbing School volunteered one of their lead SPI guides for the event and Andrezejczak also mentored climbers.

“I am passionate and I feel very compelled to mentor other climbers to pursue their own personal dreams and aspirations,” says Andrezejczak.

Andrezejczak instructing participants on ice screw placement. PC: AAC member Ben Garza

Everyone was asking questions, not quite sure what to expect on the first day. Participants swung their tools nervously as ice rained down from above at Pitchoff Quarry, a popular ice climbing destination, featuring stunning cliffs of cascading ice. Off to the side, mini-seminars were held, climbers listened eagerly, ready to learn.

The next day, the group of climbers trekked across a snow-covered Chapel Pond to Positive Reinforcement, a wide flow of ice that offers a variety of climbs. Andrezejcak watched as the novice ice climbers fit their own crampons to their boots. Excitedly, climbers placed ice screws while top-roping, practicing their newfound skills. Some climbers launched themselves off the ground and onto the ice, practicing their ice dyno.

“The second day everyone was self-functioning ice climbers like they graduated with an ice climbing diploma,” says Andrezejczak.

The group even held an ice climbing speed competition. Each team climbed one of two neighboring routes. Competitors had to place two ice screws anywhere on the climb. It didn't matter where, as long as it was off the ground. Andrezejczak’s team's strategy was light and fast. Place the screws immediately and then climb up. The other team had the total opposite approach. Go fast and ditch your screws later, when you're tired so you can rest.

The energy was addictive. “We just want to be a conduit for ice climbing,” says Andrezejczak.

After the event, Andrezejczak ran into two participants from the New Ice Climber Weekend at his local climbing gym. Weeks later, both climbers were still stoked about the New Ice Climber Weekend.

PC: AAC member Ben Garza

Looking for a community of like-minded people and climbing partners, Andrewzejczak, joined the AAC in 2015. He began by volunteering, and while living out in California, he helped establish the AAC San Diego Chapter. Andrzejczak loved that the AAC cultivated an environment that encouraged mentorships in a varity of climbing disciplines.

When Andrezejczak moved to Washington, D.C. he inserted himself in the D.C. section leadership and ice climbing community. If you want to stay active in the winter on the east coast, naturally the next step is ice climbing.

“I feel I'm more appreciative of ice climbing because of the uniqueness,” says Andrezejczak. “Things don't come in every year, so whenever you get on a route, that's a rare formation. That just gives [me] more appreciation and fulfillment.”

PC: AAC member Ben Garza

There are plenty of resources available for members of the D.C. Chapter who are interested in trying ice climbing. Andrezejczak hopes this can be a continuous opportunity that the D.C. section offers to members. Novice ice climbers can take advantage of the $30 a year gear closet that PATC offers as well. Finances should not be a burden.

“This can be your gateway to becoming an alpinist,” says Andrezejczak.

land of the Ho-de-no-sau-nee-ga (Haudenosaunee) and Kanienʼkehá꞉ka (Mohawk).

United Through Adventure

The AAC Eastern Sierra Chapter Welcomes All Types of Adventurers

Grassroots: Unearthing the Future of Climbing

By Sierra McGivney

“Everyone has great stories, they don't all need to be climbing El Cap in a speed ascent,” says Brice Pollock.

For Brice Pollock, the AAC’s Eastern Sierra Chapter Chair, the Adventure Reports began back in 2017 in the San Francisco Bay Area. The idea behind the event was to build community through storytelling about what adventure means to you.

PC: AAC Member Jaymie Shearer

Pollock began climbing like most of us—through a friend. He fell in love with the movement and how climbing challenged his mind. The grading system became addictive. He first started climbing in the gym eight years ago and then transitioned to trad climbing.

“[Climbing] is so broad that the broadness has really kept me interested in all the different techniques over time,” says Pollock.

When Pollock moved out of the Bay Area to Mammoth Lakes two and a half years ago, he had a hard time building a community. His friend was running a climbing club at Mammoth High School. Pollock pushed to merge the Adventure Reports with the climbing club. The Eastern Sierra AAC chapter was born.

“It's cool to help build this community,” says Pollock.

A core group of members attend events but Pollock is always trying to reach out to others and expand the chapter. The chapter’s mission is to be inclusive, hence the “whatever adventure is to you”.

Watching the journeys people have with the outdoors is one of the most enjoyable aspects of the Adventure Reports for Pollock. Pollock came in to the mountains as an adult. He has an affinity toward others whose journey is just beginning.

Provided by AAC Chapter Chair Brice Pollock

One woman told the story of her entry into the outdoors and how she progressed over time. First she went on long hikes, then backpacking trips, and then began thru-hiking. She ended her report with pictures of her scrambling in alpine terrain.

“There is this picture of her on this knife edge arete that sticks out in my head,” says Pollock.

Seeing others share their origin stories is both valuable and vulnerable. Being able to convey that you didn't always have these skills, and risk tolerance, shows humility. Someone new to the outdoors could be sitting in the audience feeling overwhelmed, thinking, “I could never thru-hike or climb multipitches.” It is important to exhibit that everyone was once a beginner. People aren’t born climbing trad and alpine routes. Everyone has to start somewhere and build their skill set.

AAC Member Jaymie Shearer

The Adventure Reports has created a community of like minded people who inspire each other with their stories, and connect to pursue new adventures. Pollock’s friends Brian and Hannah moved out to Mammoth and were looking to make friends and partners. Through the Adventure Reports they were able to build a group of friends to go backcountry skiing, running, and climbing.

Pollock and a couple of his friends have experienced this inspiration firsthand. During one Adventure Report event, a participant shared about the old overgrown hiking trails in Yosemite that are rarely traveled. The participant shared about trekking through tall slick grass on steep trails, venturing into less traveled paths in one of the most visited National Parks in the country. Then the person went on to canyoneer Middle Earth, in lower Yosemite Falls. The precarious trek provided for a great adventure.

“We actually went and did Middle Earth, me and some of my friends and that was our inspiration for that objective,” says Pollock.

Before the pandemic, Adventure Reports were held potluck style in people’s homes. Everyone would bring food and present their adventures. Pictures of climbers in cracks, topo maps, and smiling faces flashed across projector screens as people presented their stories.

“It’s like a friend of a friend telling a story,” says Pollock.

During the pandemic a couple of zooms were held but people were experiencing screen burnout. As the world started opening back up again, the Adventure Reports evolved into outdoor events. TV’s and projectors were hauled outside in the summer time.

PC: AAC Chapter Chair Brice Pollock

With COVID-19 restrictions lifting this past winter the Adventure Reports moved to local breweries. The reports became more communal. Locals grabbing a beer would listen in on the reports and ask questions. All kinds of people are drawn to the mountains and the culture surrounding it.

Pollocks wants to transfer back to hosting the Adventure Reports potluck style at people’s houses. Holding the reports at members houses allows people to have more intimate and deeper conversations about the outdoors.

Coming together over food and mountains builds a community of outdoor recreators with diverse objectives. Adventure brings us together and binds us. From big wall climbing in Yosemite to thru-hiking the Pacific Crest Trail, everyone has a story to share.

Texas Climbing On a New Course

AAC Austin Chapter members develop a new wall at Continental Ranch

AAC member Andrew Horton climbing Tomahawk, a 5.11- in the Weir Dam area. PC: AAC Austin Chapter Chair Brian Deitch.

Grassroots: Unearthing the Future of Climbing

By: Sierra McGivney

If you want world-class climbing in Texas, you have to earn it. You’d have to drive down a rugged ten-mile road for an hour with no service while simultaneously opening and closing gates and avoiding ranch animals. Then you’d arrive at the Butt Campground, perched atop a cliff, overlooking the beautiful blue Pecos River that cuts through sweeping limestone cliffs extending for miles.

Climbers must then trek down third-class trails down to respective climbing areas while hauling gear. Watch out for baby goats and prickly cacti. But the flora and fauna aren’t all you have to worry about at the Continental Ranch.

“The limestone against your skin feels like the most abrasive sandpaper that you've ever touched, which means you don't need chalk,” says Emilie Hernandez, one of the new route developers at the ranch.

AAC memeber Matt Langbehn. PC: AAC Austin Chapter Chair Brian Deitch.

Emilie says, if you work with the rock, the rock will work with you. If your moves are haphazard and finicky you’ll bleed. Small huecos, the size of coins, create a wave of ripples in the cliffs. Climbers can either palm the huecos like slopers or sink their fingers into near-perfect handholds.

“The word pristine is what comes to mind,” says Hernandez.

Fewer cams and hands have left their mark at the Ranch than in other areas in Central Texas. In CenTX, shining limestone is a common sight. Polished routes steer locals away from overused crags. A lack of accessible climbing in Texas has worn down cliffsides and left routes sandbagged.

PC: AAC Austin Chapter Chair Brian Deitch.

Continental Ranch is a private ranch on the Pecos River in west Texas, and it just happens to have some of the best climbing in Texas. Every type of climbing you can imagine exists here: slab, delicate face climbing, overhangs and even a bit of crack, off-width, and bouldering.

AAC member Sean Moorehead Belying Andrew Horton. PC: AAC Austin Chapter Chair Brian Deitch.

In the early 2000s, a geologist from the University of Texas was kayaking down the Pecos River studying the different striations in the bluffs at Continental Ranch. The geologist happened to be friends with Jamie McNally, a former Access Fund President and local climber. McNally noticed right away that the 300-foot limestone cliffs contained the potential for climbing. The two approached the previous ranch owners, Marilyn and Howard Hunt, about gaining access to these untouched cliffs.

According to a Rock and Ice article by Jeff Jackson, the ranch was struggling financially due to overgrazing and an infestation of dog cactus, so the Hunts opened up the ranch to climbers in 2004 with a fee of $10 to camp and climb.

Climbers soon dotted the limestone cliffside, putting up routes like Crackalious, a 5.10 sport route, and Crocodile Tears, a slabby 5.11 sport route with pinchers, slopers, and mirco-huecoes.

McNally was the first person who developed a relationship with the Hunts and was good friends with the son of the family, Howard Hunt Jr. (aka Mister). Mister, Jeff Jackson, and Scott Melcer were some of the first developers on the ranch. This continued for about four or five years until the ranch closed to climbers due to a liability standpoint.

AAC member James Faerber teaching participants at the Continental Ranch Round-Up. PC: AAC Austin Chapter Chair Brian Deitch.

In 2017, McNally approached Heather and Miles Gibbs, the current ranch owners and operators of the Continental Ranch Pecos River Expeditions, with a plan to reopen Continental Ranch to climbers. Climbing leaseholders and guide services now have access to the ranch. The Ranch even hosts a climbing festival twice a year, the Continental Ranch Round-Up.

Brian Deitch is a full-time lawyer and a part-time route developer at Continental Ranch. When Deitch isn’t practicing law he spends his weekends in the hot Texan sun drilling bolts into limestone. He arrives late Friday night in Del Rio, works hard Saturday into midday Sunday, until he has to make the trek back to Austin.

AAC member Guy Tracy climbing in the Painted Canyon Sector. PC: AAC Austin Chapter Chair Brian Deitch.

“The second we cross through the gates of the ranch it’s like the world melts away,” says Deitch, the AAC Austin Chapter Chair.

Deitch got involved with the AAC after attending the Red Rocks Rendezvous and connecting with AAC members and volunteers. In 2017 Adam Peter, the former National Volunteer Programs Manager for the AAC, sent out an email looking for members to get involved locally. Deitch responded and started the AAC Austin Chapter.

About a year later the AAC Austin Chapter and the Access Fund joined forces with Outpost Wilderness Adventures to host the Continental Ranch Round-Up.

Over drinks and celebration at an Access Fund happy hour in 2019, Deitch met Hernandez. Hernandez, the founder of the Texas Lady Crushers, was interested in the Ranch Round-Up but was unable to attend the previous year. Deitch mentioned he was “the liaison” for the Continental Ranch Round-Up. Hernandez’s interest was piqued.

“Are you interested in mentoring a climber? I heard you climb trad,” says Hernandez.

The two are now married and route developers at the Ranch.

Deitch and Douglas McDowell, the events chair for the AAC Austin Chapter, teamed up to work with Heather Gibbs on new route development at the ranch. The two walked around the estimated 30,000 acre property showing her possible climbing walls and explaining elements of route development. As time went on, she herself began to point out areas she thought would be good for climbing.

On January 8, 2021, they found a wall along the Pecos River that seemed to feature just about everything: jugs, cracks, crimps, aretes, and slabs. Over the course of eight weekends, Deitch and a select group of climbers took on Heather’s Wall.

AAC member Emilie Hernandez developing Heather’s Wall. PC: AAC Austin Chapter Chair Brian Deitch.

For the entire month of January, Deitch spent every weekend at Continental Ranch. That’s ten hours of driving each weekend.

“It's not somewhere I can just go to after work,” says Deitch.

Deitch fell in love with the process of cleaning stone and developing routes. He financed the entire operation. This includes drills, drill bits, anchors, bolts, and mussey hooks. Both Deitch and McDowell studied and met with mentors throughout the process. They wanted to develop routes correctly and be able to educate others; no one-move wonders, no grid bolting, and consistently graded routes.

“There's just something really badass about having a drill in your hand, hanging on a fixed-line and knowing that this is going to be a route that my friends are going to climb and a legacy that I'm literally leaving until that gear wears out or the rock crumbles,” says Hernandez.

Heather’s wall. PC: AAC Austin Chapter Chair Brian Deitch.

Walk past Piranha, a 5.9 route at Painted Canyon's Bone Yard area for about a quarter-mile and you’ll come face to face with Heather’s Wall. Six new routes were developed over the last year with room for more. Flyin’ Brian, a difficult 5.10+, features tricky face moves that will lead you into a corner, below an overhang, forcing climbers into “a pistol squat from hell” in order to pull the roof. Baby Goat, inspired by all the little goats running around the ranch, is a 5.10- face climb through a crack. My Mija, is a well-protected 5.10, and leads climbers to choose their own adventure by providing three variations along and to the sides of the bolt line. A technical 5.11, Matriarch runs parallel to My Mija. Slim Picken’s is a 5.11 developed by Scott Davis. Finally, at the far right of the wall, there is Bree Jameson’s climb, which she onsighted and self-belayed from the ground up—Learning from Legends, a 5.6.

“It’s the best limestone north of the Rio Grande,” says Deitch.

Hernandez’s and Jameson’s routes are the only two developed by women of color on the ranch. This inspired both climbers to give other women the opportunity to climb and learn about route development. The Texas Lady Crushers had their first retreat on the ranch last March.

“You can be anybody you want to be out there as long as you respect the land, respect the people, and respect the people who came before you,” says Hernandez.

PC: AAC Austin Chapter Chair Brian Deitch

Thanks to Gibbs and her desire to open her mind, Texas climbing is on a new course. Deitch, Hernandez, and other climbers will continue to explore and develop more routes at the ranch. If you get the chance to climb at Continental, make sure to stop and look out at the vast mountainous desert.

“You feel like a real deal climber out there,” says Hernandez.

Climbing Through Language

The AAC DC Chapter takes Wilderness Kids Alexandria climbing

PC: Elizabeth Waugh

Grassroots: A storytelling series about cutting edge projects and conversations in the AAC community.

By Sierra McGivney

All Melissa Rojas knew about rock climbing was kids' birthday parties. But once she started climbing, pulling herself up multicolored plastic holds with her long-time climber friend, her mind was free. The stress of working in healthcare melted away. Each move she made was related to each other, connected to the whole route, like piecing together a puzzle.

“I just got hooked,” says Rojas, the Communications Co-Chair for the AAC D.C. Chapter.

Climbing engrossed Rojas. She wanted to get involved and give back, so she looked into climbing organizations and found the American Alpine Club.

PC: Elizabeth Waugh

As Rojas got more engaged in the climbing community, she noticed a sizable amount of Spanish-speaking climbers in the area and saw an opportunity for community. In June of 2021, Rojas founded ¡Escala DC!, a Spanish-speaking climbing club.

Although not all spanish-speakers are people of color, differences in language, and the culture embedded in language, can be a barrier to feeling fully understood and represented in a community. And when language and racial identity overlap, it can be even harder to see yourself represented.

“If you're not white, it can feel very intimidating going into a gym.” says Rojas, “It's not like anybody's doing anything to make you feel intimidated, you just feel intimidated.”

Members of ¡Escala DC! feel grateful to have found a group that speaks to them. The club organizes weekly meetups at gyms in the area like Crystal City, Timonium, and Rockville. Rojas has created a space that unites climbers whose identities come from a Spanish-speaking background.

PC: Elizabeth Waugh

Although spanish-speakers in the US come from a wide range of countries and cultures, there is no denying the way language can bind you together. “It's a different experience when you climb with folks that have the same cultural context,” says Rojas.

Jerry Casagrande didn’t grow up in a particularly outdoorsy family. He never went hiking or camping. When he was 15 years old his science teacher suggested he look into a summer program that would take him to the Grand Tetons in Wyoming, the Bear Creek Mountains in Montana, and Yellowstone. The grand mountains and forests of the West left a lasting mark on Casagrande.

“It just changed my life completely,” says Casagrande.

PC: Elizabeth Waugh

In a number of ways, Casagrande has sought to pay that experience forward. He ran a program about 20 years ago that took kids from all over the country to experience the outdoors. In Alexandria, Casagrande’s home, he noticed that there was an imbalance between kids who had access to green spaces and those who did not. In October of 2021, Casagrande founded Wilderness Kids Alexandria.

WKA believes there are a multitude of benefits to being outside. The mission of the nonprofit organization is to provide life-enriching experiences in nature to teenagers from under-resourced families in Alexandria, Virginia.

Latino Outdoors is a “volunteer-driven organization that focuses on expanding and amplifying the Latinx experience in the outdoors.” Casagrande posted on the Latino Outdoors DMV—D.C., Maryland, and Virginia—Facebook page looking for volunteers to take kids climbing. A number of people are also a part of the AAC D.C. section. He got an overwhelming response.

PC: Elizabeth Waugh

“We had more volunteers than we could use,” says Casagrande.

Members from the AAC D.C. section, ¡Escala DC!, and the Potomac Mountain Club volunteered to belay kids and teach climbing basics on February 19, 2022, at Movement Climbing gym.

After a picnic, kids headed to Movement to get fitted for climbing shoes and harnesses. Many looked up at the rainbow of holds that create routes and said, “I can’t do that.” By the end of the day, participants were practically racing up the wall.

English is not a first language for a majority of the kids who attended. The volunteers were able to speak to kids in their native language. This enabled the kids to easily communicate on the climbing wall and meet passionate climbers who spoke the same language as them. Seeing themselves reflected in this space helped to cultivate a sense of self within the climbing community.

“It was super cool to be able to talk to them in their mother language and have them feel reassured,” says Rojas.

PC: Elizabeth Waugh

The AAC, along with PATC took kids climbing at Caderock on Apr 23, 2022. WKA was hoping to get 20 kids in attendance. Ten kids climbed while the other 10 kids went hiking. Mid-day they switched. Volunteers set up topropes and taught kids climbing basics.

Rojas believes fostering and establishing strong cultural diversity and ability diversity in the climbing community is the keys to true accessibility. It’s a team effort to establish a space accessible to all. Multiple organizations came together to nourish a love of climbing in kids who otherwise might not have the opportunity.

“We're a really small organization and [the AAC] enables us to have a bigger impact than we could otherwise possibly have,” says Casagrande.

Keep Climbing Clean

The AAC L.A. Chapter organizes a clean-up at Stoney Point

PC: AAC L.A. Chapter Chair Alex Rand

Grassroots: A storytelling series about cutting edge projects and conversations in the AAC community.

by Sierra McGivney

Thirty seconds off of 118 FWY and Topanga Canyon, Stoney Point welcomes climbers and hikers. Brittle sandstone boulders tagged with graffiti and spotted with white chalk contain almost 100 years of climbing history. Located just north of Los Angeles, this crag provides convenient access to stellar climbing, minutes away from the city. This small climbing destination features various highball boulders with thought-provoking problems and exciting top-outs.

Stoney Point was initially developed in the late ’20s and early ’30s. Glen Dawson, a mountaineer and longest-tenured Sierra Club member, led Sierra Club outings to Stoney Point.

Big names like Royal Robbins, Yvon Chouinard, and Bob Kamps developed routes on the boulders of Stoney Point. Chouinard's Hole, a V2 boulder problem, is a notable route that requires the climber to execute a grovely mantel into a scoop. Stoney was a practice ground for bigger projects, mainly groundbreaking first ascents involving free climbing, such as the Salathé Wall in Yosemite Valley.

PC: AAC L.A. Chapter Chair Alex Rand

Today, Stoney Point is akin to an outdoor climbing gym. A community of local climbers spends their days perusing boulders and climbing top-ropes. Climbers grab hold of textured slopers and in-cut crimps crafted from fine-grain sandstone. Stoney Point is home to just under 300 routes. One of the climbers you’d see milling around is Alex Rand, the American Alpine Club Chapter Chair for the Los Angeles Section.

“You'll see the same people day in and day out go over to [Stoney Point], climbing their favorite routes, guiding people who are trying to find a boulder that might be a little more obscure, encouraging people or sharing crash pads,” says Rand.

Amid all of the crash pads and climbers, glass bottles, rusty nails, and other trash litter Stoney Point. The crag is in a prime location for people to discard trash as they drive by on the highway, or to spray paint the rocks these climbers call home.

AAC member Jennifer Zhu

“It's kind of interesting because it's such a prolific climbing destination, and it is so— what's the word?— it's so unimposing when you get there it is sort of this park that is littered with broken glass, empty bottles, and graffiti all over the rocks,” says Rand.

On Jan 23, 2022 the AAC’s L.A. Chapter, along with Trail Mothers and Sender One Climbing Gym, organized a clean-up of Stoney Point. Fifty people showed up. A mix of rock climbers, gym climbers, and hikers participated in the event. The large turnout was unexpected.

“We almost didn’t have enough trash bags for everyone,” says Rand.

By noon, volunteers collected over 200lbs of trash. Old luggage and motor oil cans were some of the most notable trash collected.

After the event, a core group of people stayed to climb and encouraged others to join them. Seasoned climbers of Stoney Point gave beta on route-finding to new climbers. Everyone set up their crash pads next to one another, sharing gear and beta.

AAC member Jennifer Zhu

One of the fundamental parts of the clean-up is bringing people together through climbing. Rand sees this as a great opportunity to expand and strengthen their community while making new friends and climbing partners.

“You get to meet a diverse group of people who live all over L.A. and who have all sorts of backgrounds and experiences with the American Alpine Club and climbing,” says Rand.

The L.A. chapter does crag clean-ups every couple of months in the surrounding L.A. area. Even with these clean-ups, trash still remains at Stoney Point. More graffiti appears on boulders and rock walls in the weeks afterward. Tiny shards of glass get simultaneously kicked up and buried in the sand.

“I think that it's essential for the health and well-being of Stoney Point to continue to do these cleanups,” says Rand.

For the next clean-up, on Earth Day, April 9, Rand and Kristen Hernandez of Trail Mothers are coming equipped with colanders and sifters. The L.A. AAC Chapter, Trail Mothers, and the Stoney Point community will continue working to preserve and rehabilitate the boulders, rock walls, and trails of Stoney Point.

AAC member Jennifer Zhu

At Stoney Point, people are creating a community built on crag stewardship. Instead of rejecting the new wave of climbers, Stoney Point welcomes newcomers in, while also teaching conservation and safe climbing practices. There is something for everyone at Stoney Point.

The Prescription - February 2021

Highline anchor bolts atop the northwest corner of Castleton Tower, Utah.

The Prescription - February 2021

STRANDED – STUCK RAPPEL ROPES

CASTLETON TOWER, UTAH

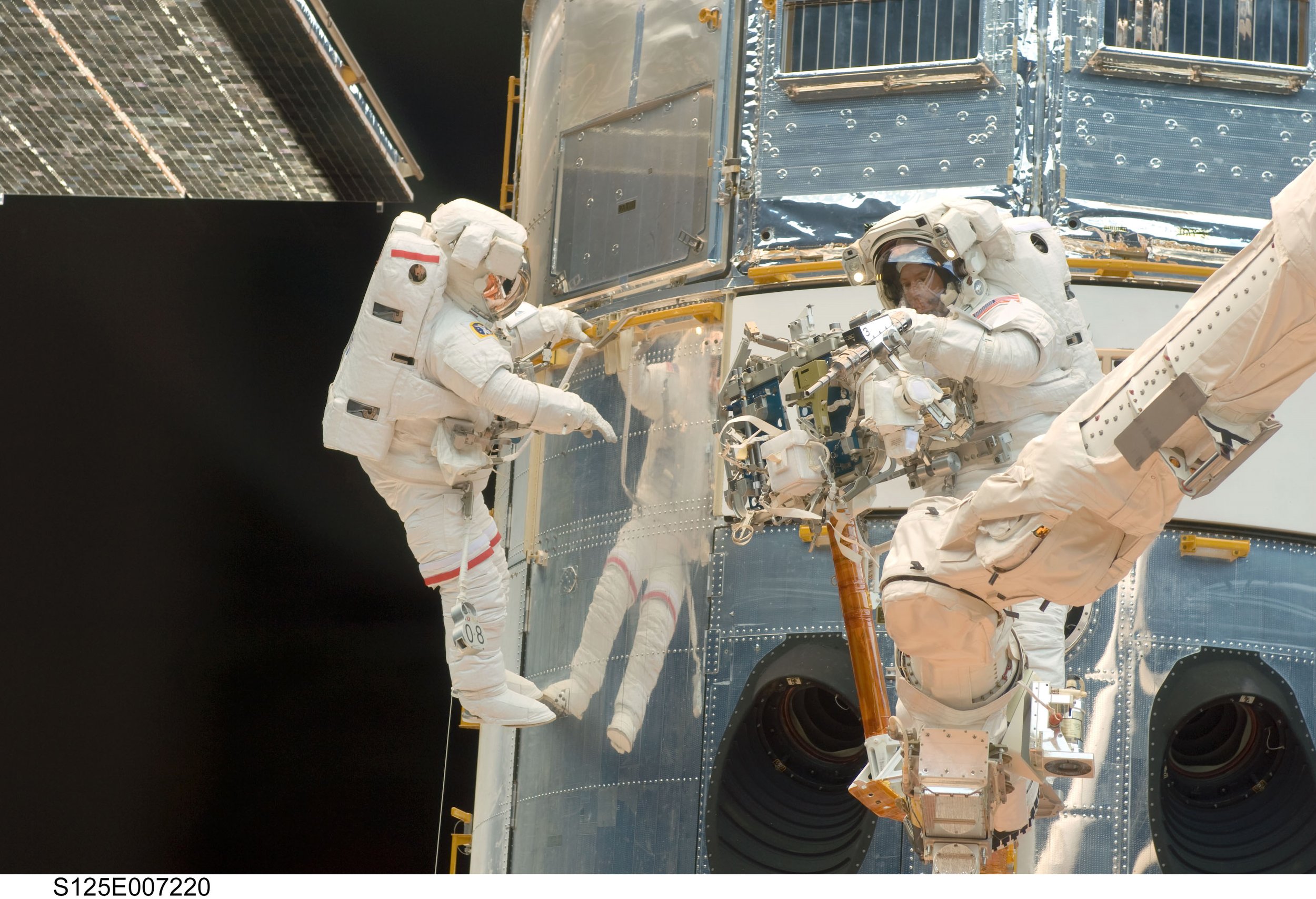

Just after sunset on December 4, two male climbers (ages 32 and 36) called 911 to report they were stranded halfway down 400-foot Castleton Tower because their rappel ropes had become stuck. Starting near sunrise, the pair had climbed the classic Kor-Ingalls Route (5.9) on the tower’s south side. They topped out later than expected, with about an hour and a half of daylight left.

Armed with guidebook photos and online beta, they planned to descend via the standard North Face rappels. The two saw a beefy new anchor on top of the northwest corner of the tower and decided this must be the first rappel anchor. Tying two 70-meter ropes together, the first rappeller descended about 200 feet and spotted a bolted anchor 25 feet to his right, with no other suitable anchor before the ends of the ropes. No longer in voice contact with his partner, he ascended a short distance and moved right to reach the bolted anchor. It appeared that one more double-rope rappel would get them to the ground. Once both climbers reached the mid-face anchor, they attempted to pull the ropes. Despite applying full body weight to the pull line, they could not get the ropes to budge.

Contemplating ascending the stuck rope, the climbers realized the other strand had swung out of reach across a blank face. The climbers agreed that recovering the other strand was not safe or practical, nor was climbing the unknown chimney above them in the dark. The climbers were aware the temperature was expected to drop to 15°F overnight, so they made the call for a rescue. They were prepared with a headlamp, warm jackets, hand warmers, and an emergency bivy sack.

A team of three rescuers from Grand County Search and Rescue was transported to the summit via helicopter. One rescuer rappelled to the subjects around 9 p.m. and assisted them in rappelling to the base of the tower.

ANALYSIS

The rescuers discovered the climbers had mistakenly rappelled from an anchor used to rig a 500-meter highline (slackline) over to the neighboring Rectory formation. Instead of rappelling the North Face, as planned, the climbers had ended up on the less-traveled West Face Route (5.11). Because the highline anchors were not intended for rappelling, friction made it impossible for the climbers to pull their ropes.

Upon reflection, the climbing party identified a number of decisions that could have prevented this misadventure. Had they abandoned the climb and rappelled the Kor-Ingalls Route earlier, they probably would have been down before sunset. Even after finishing the route, heading back down the Kor-Ingalls would have had the advantage of familiarity with the anchor stations rather than rappelling into unknown territory. Lastly, while the highline anchor is quite visible atop the tower, its configuration, set back from the cliff edge with very short chain links, indicates it is not appropriate for a rappel. The climbers may have felt rushed with the setting sun and dropping temperatures, but if they had looked more thoroughly, they likely would have found the North Face rappel station, about 15 feet away . This anchor’s bolts have three or four feet of chain that extend over the edge and attach to large rappel rings, making for an easy pull. (Sources: The climbers, Grand County Search and Rescue, and the Editors.)

The Hazards of Highline Anchors

As highlines, BASE jumps, and space nets grow in popularity, the number of nonclimbing bolted anchors is on the rise at certain climbing areas, and rescues like this are becoming more prevalent. In fact, this is the second stranding in five years resulting from an attempted rappel using the same highline anchor on Castleton Tower. Two very similar incidents were reported in ANAC 2019: one at Smith Rock, Oregon, and one in Clear Creek Canyon, Colorado.

The highline from Misery Ridge to Monkey Face at Smith Rock. Climbers were stranded in 2018 when they attempted to rappel from the anchors on the left and could not pull their ropes. Photo courtesy of Smithrock.com.

To avoid mistakenly using an anchor that’s not intended for rappelling, study published descriptions of anchor locations carefully. If an anchor does not appear to be set up properly for rappelling—especially when it’s on a very popular formation like Castleton Tower—look around and consider the options before committing to the rappel.

After word got out about these stranded climbers on Castleton Tower, a local guide removed the chain links from the highline anchor to discourage future incidents. (The links can easily be reinstalled to rig the highline to the Rectory.) Plans are in the works to attach plaques identifying the bolts as a highline anchor.

THE SHARP END: A SKIER’S SCARY SLIDE ON MT. HOOD

Last June, a 25-year-old skier had just begun his descent from Mt. Hood’s summit when he missed a turn and started sliding. Waiting at the bottom was a fumarole: an opening in the volcano’s icy surface that emits steam and noxious gases. In episode 61 of the Sharp End, this skier tells host Ashley Saupe about his accident and ensuing rescue. The Sharp End podcast is sponsored by the American Alpine Club.

Climbers and Fumaroles

Fumarole incidents on Oregon’s Mt. Hood are not uncommon. These dangerous volcanic vents form in the run-out zone below several of Hood’s most popular summit routes. In December 2020, another skier fell through a thin bridge over a fumarole on Mt. Hood. Like the skier in this month’s Sharp End, she was traveling alone, and she was fortunate that bystanders quickly came to her aid. Although traditional crevasse hazard is seldom an issue on Hood’s normal routes, solo climbers and skiers should be acutely aware of fumarole dangers, how to identify them, and their likely locations. For more on Mt. Hood’s common accident types, see “Danger Zones” in ANAC 2018.

OMG! THIS BOLT IS LOOSE!

According to the New River Alliance of Climbers (NRAC) in West Virginia, 75 percent of the “bad bolt” reports it receives are simple cases of loose nuts that could be tightened easily. This fun, one-minute video from the NRAC offers a quick breakdown of what to do when you encounter a loose bolt—which can be tightened and which should be reported to your local climbing organization or BadBolts.com.

MEET THE VOLUNTEERS

Stacia Glenn, Regional Editor for Washington

Years volunteering with Accidents: 5

Stacia Glenn near Washington Pass. Photo by Jon Abbott

Real job: Breaking-news reporter at The News Tribune in Tacoma

Home climbing areas: North Cascades, Exit 38, Vantage/Frenchman Coulee

Favorite type of climbing?

I love single-pitch sport—there's just something about the mental and physical challenge of finding my way up the rock, and that's where I push my ability the furthest. But the overall experience of alpine climbing—the isolation, the mountain views, the promise of adventure—is hard to beat.

How did you first become interested in Accidents?