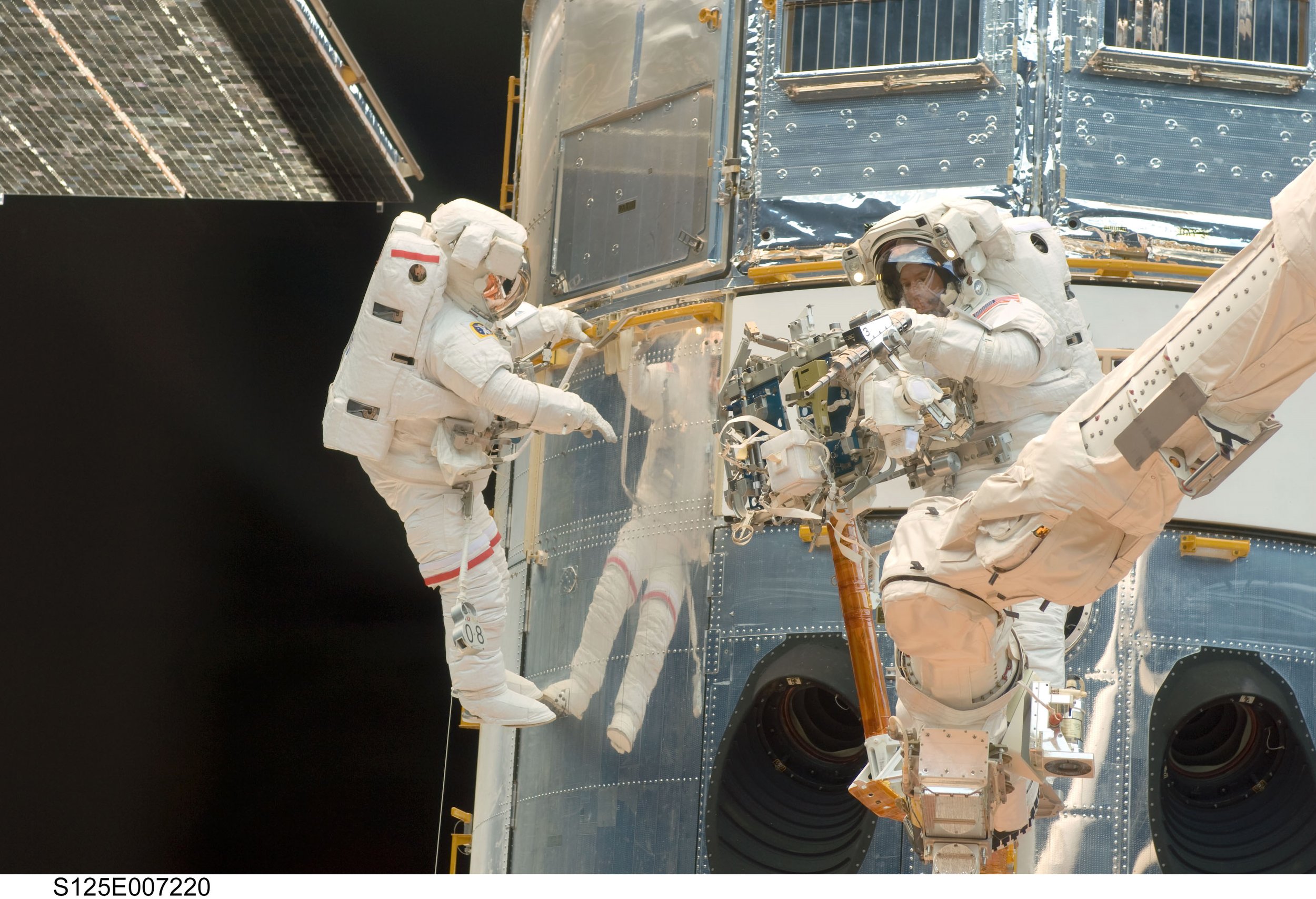

Photo courtesy of the Grunsfeld Collection.

No Mountain High Enough

The Intersections between Space Travel and High-Altitude Mountaineering

Member Spotlight: Dr. John Grunsfeld, Astronaut

By Hannah Provost

Spacewalking outside the Hubble Space Telescope, John Grunsfeld wasn’t that much closer to the stars than when he was back on the surface of Earth, but it certainly felt that way. The sensation of spacewalking, of constantly being in freefall, but orbiting Earth fast enough that it felt like weightlessness, was more of a thrill than terrifying. Looking out to the vaster universe, seeing the moon in its proximity, the giant body of the sun, stole his breath away. Grunsfeld was experiencing a sense of exploration that very few humans get to. It was deeply moving, a sensation he also got in the high glaciated ranges when he’d look around and be surrounded by crevasses and granite walls of rock and ice. Throughout his life, he couldn’t help but seek out the most inhospitable places on the planet, and even beyond.

You might think that there is nothing similar between climbing and spacewalking. But when you ask John Grunsfeld, former astronaut and NASA Chief Scientist—and an AAC member since 1996—about the similarities, the connections are potent.

The focus required of spacewalking and climbing is very much the same, Grunsfeld says. Just like you can’t perform at your best on the moves of a climb high above the ground without intense focus on the next move and the currents of balance in your body, so, too, suited up in the 300-pound spacesuit, with 4.3 pounds per square inch of oxygen, and 11 layers of protective cloth insulation, you still have to be careful not to bump the space shuttle, station, or telescope as you go about the work of repairing and updating such technology—the job of the mission in the first place. Outside the astronaut’s suit is a vacuum, and Grunsfeld is not shy about the stakes. “Humans survive seconds when vacuum-exposed,” he says. With such high risks, it’s a shame that the AAC rescue benefit doesn’t work in space.

Not only is spacewalking, like climbing, inherently dangerous, it also requires intense focus, and it can be a lot like redpointing. Grunsfeld reflects that “it’s very highly scripted. Every task that you’re going to do is laid out long before we go to space. We practice extensively.” In Grunsfeld’s three missions to the Hubble Space Telescope, his spacewalks were a race against the clock—the battery life and limited oxygen that the suit supplied versus the many highly technical tasks he had to perform to update the Hubble instruments and repair various electronic systems. It’s about flow, focus, and execution—skills and a sequence of moves that he had practiced again and again on Earth before coming to space. Similarly, tether management is critical. Body positioning, and not getting tangled in the tether, is important in order to not break something—say, kick a radiator and cause a leak that destroys Hubble and his fellow astronauts inside. But to Grunsfeld, the risk is worth it. The Hubble Space Telescope is “the world’s most significant scientific instrument and worth billions of dollars. Thousands of people are counting on that work.”

Indeed, perhaps a little more is at stake than a send or a summit.

Grunsfeld climbing at Devil’s Lake, WI. Land of the Myaamia and Peoria people. Photo by AAC member Tom Loeff.

Growing up in Chicago, Grunsfeld’s mind first alighted on the world of science and adventure through the National Geographic magazines he devoured, and a school project that had an outsized effect. Grunsfeld’s peers were assigned to write a brief biography of people like George Washington and Babe Ruth. Rather than these more familiar figures, Grunsfeld was assigned to research the life of Enrico Fermi—a nuclear physicist who was instrumental in the Manhattan Project, the creator of the world’s first artificial nuclear reactor, and a lifelong mountaineer. Suddenly, science and the alpine seemed deeply intertwined.

Grunsfeld started climbing as a teenager, top-roping in Devil’s Lake, back when the cutting edge of gear innovation meant climbing by wrapping the rope around your waist and tying it with a bowline. Attending a NOLS trip to the Wind River Range and further expanding on his rope and survivor skills truly cemented his love of climbing in wild spaces. Throughout the years, climbing was a steady beat in his life, a resource for joy. He would climb in Lumpy Ridge, the Sierra, the White Mountains of New Hampshire, Tahquitz, Peru, Bolivia, and many other places with his wife, Carol, his daughter, and close friends like Tom Loeff, another AAC member.

If climbing was a steady beat, his fascination with space and astrophysics would be a starburst. At first, his application to become a NASA astronaut was denied, but in 1992, Grunsfeld joined the NASA Astronaut Corps. It would shape the rest of his life’s work. Between 1995 and 2009, Grunsfeld completed five space shuttle flights, three of which were to the Hubble Space Telescope—which many consider to be one of the most impactful scientific tools of modernity, because of how its 24/7 explorations of space have informed astronomy. On these missions, Grunsfeld performed eight spacewalks to service and upgrade Hubble’s instruments and infrastructure. Over the course of his career, he has also served as the Associate Administrator for Science at NASA and the Chief Scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC. His own research is in the field of planetary science and the search for life beyond Earth.

Grunsfeld [left] and team on the summit of Denali (Mt. McKinley), Denali National Park, AK. Photo provided by Grunsfeld Collection.

But in 1999, even with two space missions under his belt, Grunsfeld couldn’t get the pull of high-altitude mountaineering out of his mind. He has an affinity for the adventure of exploring some of the most adverse places humans have ever explored. He was ready for his next great adventure. He wanted to climb Denali (Mt. McKinley).

Many aspects of Grunsfeld’s Denali saga are familiar. Various trips resulted in unsuccessful summit attempts: from a rope team he didn’t fully trust, to eight days at the 17,000-foot high camp with bad weather. On his 2000 attempt, he was followed around by cameras for a PBS special that never came to fruition, and he attempted an experiment about core temperatures in high-altitude terrain using NASA technology. Ultimately the expedition came back empty-handed—without a summit and with a faulty premise for their measurements of core temperature. When he returned in 2004 with a team of NASA colleagues, Grunsfeld was able to stand atop Denali and take in the jagged peaks all around him.

The connections between climbing and space travel aren’t limited to the physical demand, focus, and calm required. Both activities are inherently dangerous, and nobody participating in either of these activities has been left unscathed. Just like how many climbers have had a friend or an acquaintance experience a significant climbing accident, Grunsfeld knew the true danger of space travel. In 2003 while Grunsfeld was still in Houston, one of the most tragic space shuttle disasters in American space history occurred. On reentry into the atmosphere, the space shuttle Columbia experienced a catastrophic failure over East Texas. According to NASA’s website, the catastrophic failure was “due to a breach that occurred during launch when falling foam from the External Tank struck the Reinforced Carbon Carbon panels on the underside of the left wing.” Grunsfeld was the field lead for crew recovery—picking up the pieces of the disaster so as to bring the bodies of the lost crew members home. It’s no wonder that in other parts of his life and in his climbing, he is deeply committed to safety and disseminating as much climbing knowledge as possible about safety concerns.

After the Columbia disaster, Grunsfeld was often asked why he would consider going back to space when the risks were so high. On his final flight to the Hubble Space Telescope in 2009, Grunsfeld reports, there was a 62% probability that he and his team would come back alive. Those aren’t the most inspiring mathematical odds. But as a crew, and for the agency NASA, it was critical to update the technology on the Hubble Space Telescope at that time. He reflects: “It may seem crazy to fly with those odds, but in fact my earlier missions were much more risky, we just didn’t know it at the time.” In comparison, risk assessment in the mountains is considerably more individualized.

Space exploration and mountaineering also have a distinct investment in monitoring the state of our natural landscapes and environment. From space, it’s a lot easier to see how fragile and small Earth is, in the grand scheme of things. It’s also easier to see the changing climate and its impact across the planet. Putting on his scientist hat, Grunsfeld tried to capture the significance of space observations to climate research, saying, “Most of what we know about our changing climate is now from space observations, because we get to see the whole Earth all the time, and you really have to look at sea level not as a local phenomenon, but [look at] how does it change over a whole Earth for a variety of different reasons.”

From sea level rise to vanishing bodies of water, Grunsfeld has seen some dramatic changes to Earth’s surface from the first time he was in space, in 1995, to his last time in 2009. With his decades of exploration in the mountains, he’s also seen glaciers and once permanent snowfields disappear. You can tell from the passion in his voice that Grunsfeld has a keen awareness of what’s at stake as the climate changes—he’s seen it happening already.

In addition to bringing Grunsfeld to incredible places, climbing also brought him into close connection with incredible people. Grunsfeld had originally met the famous photographer, and fellow AAC member, Brad Washburn through AAC annual meetings and at Boston’s Museum of Science, where Washburn was the director for many years. Their friendship would result in two incredibly rare moments for climbing, photography, and space exploration.

Photo provided by the Grunsfeld Collection.

Washburn, the raspy-voiced photographer who was excellent at pulling off the unbelievable, was working on a documentary recreating the famous journey of the explorer Ernest Shackleton when he called up Grunsfeld for a favor. For the film crew to cross the mountainous, cold, and deeply unfriendly landscape of South Georgia just like Shackleton did in 1916 was still an incredibly unlikely feat. Luckily, Grunsfeld had what you might call “pull.”

“I was able to get space shuttle photography from a classified DOD shuttle flight which flew over South Georgia and made these huge prints for Brad,” Grunsfeld says—ultimately giving Washburn and his team the information they needed to safely traverse this rugged terrain.

But that wasn’t the end of Grunsfeld and Washburn’s story. Grunsfeld was attempting Aconcagua in 2007 when Barbara Washburn called to share the news that her husband had passed away. When Grunsfeld landed back in the States and was able to connect with Barbara on the phone, he offered to do something to honor his relationship with Washburn. His 2009 space mission was coming up, and he could take something of Washburn’s along. In the end, Grunsfeld brought Washburn’s camera from the famous Lucania expedition on his last flight to the Hubble Space Telescope. The 80-year-old camera (at the time) was used to take photographs from Hubble, including an image of the Hubble Space Telescope with Earth’s rim in the background, as seen on the back cover of this Guidebook. Washburn’s camera and the prints of the photos that Grunsfeld took remain as some of the AAC Library’s most fascinating holdings in the climbing archives.

But in fact, Grunsfeld’s (and Washburn’s) story isn’t the first to connect the vastly different fields of astrophysics and mountaineering. Lyman Spitzer, a longtime AAC member and supporter of the Club, and a prolific mountaineer, is credited for the idea that led to the Hubble Space Telescope. It almost makes Grunsfeld’s life’s work seem written in the stars.

Surprisingly, Grunsfeld reflects that there is little time for fear in space travel. Take launch, for example. The astronauts in the space shuttle are sitting on “four and half million pounds of explosive fuel,” says Grunsfeld, ticking down the seconds until they are launched into space. The launch mechanics are so powerful that within eight and a half minutes, the shuttle is traveling 17,500 miles per hour, orbiting Earth. Grunsfeld recalls that on his first mission, sitting in the flight deck of space shuttle Endeavor, at 30 seconds to launch, he heard the final instructions over the intercom: Close your visor, turn your oxygen on, and have a good flight. Was this the point he was supposed to get scared? There was no turning back, no getting off, no stopping the ride. So he didn’t let fear in. There was no use for it. And at the same time, there was so much awe that despite the risk, he felt deeply alive. It was a lot like the calm that comes with executing in the face of danger when climbing or in the mountains. In the face of danger, utter clarity.

With the focus and body awareness and rehearsal, the firsthand witnessing of our changing climate and its impacts, the risks involved and the utter sense of awe, space-walking and climbing are not as different as they might at first seem. And for Grunsfeld, one adventure could fuel another. In his downtime floating within Hubble, one of his favorite activities used to be looking back down on Earth, using a camera with a long lens to zoom in on various alpine regions—and scout the next mountain to climb.