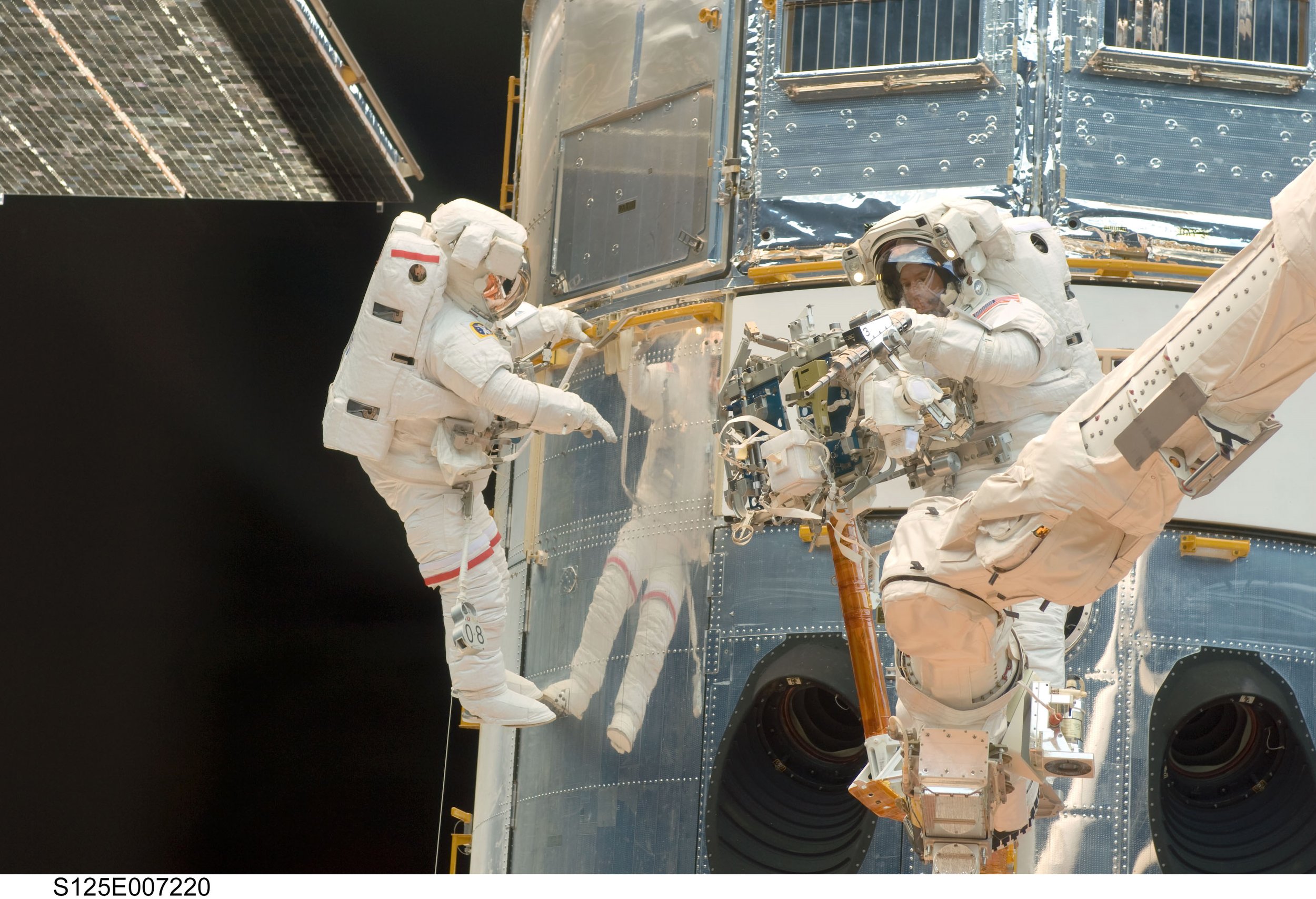

Photo by AAC member Kennedy Carey.

EXPLORE—An Act and The Act

By AAC Advocacy Director Byron Harvison

Photos by AAC member Kennedy Carey

Act

1. A thing done; a deed.

2. A written ordinance of Congress, or another legislative body; a statute.

3. A main division of a play, ballet, or opera.

Drama

1. A play for theater, radio, or television.

2. An enticing, emotional, or unexpected series of events or set of circumstances.

EXPLORE, in the waning days of the 118th Congress, met every definition of the words “drama” and “act” as it made its way into becoming law. As I sat at my computer watching Senator Joe Manchin ask for unanimous consent of the bill on the Senate floor, it was not lost on me that years of work, by hundreds of organizations, teetered on the edge of achievement. And it passed in a most glorious fashion. But let me back up just a bit...

Act 1, Scene 1

Not too long ago, in early December of 2024, the AAC policy team traveled to Washington, DC, and met up with the Access Fund and American Mountain Guides Association (AMGA). The mission was clear—examine and pursue all avenues to get the EXPLORE Act passed. At that time, attachment to the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) was still on the table, as was the possibility of being bundled in with the Continuing Resolution (CR) to keep the government funded. Additionally, there was the less probable route of the bill going “stand-alone” for a unanimous consent vote on the Senate floor, but we sensed that there wasn’t enough floor time, especially given the need to end the lame-duck session of Congress, and the condition that a unanimous consent vote had to actually be unanimous without a single dissenting vote.

Photo by AAC member Kennedy Carey.

It was an all-hands-on-deck moment for recreation-based organizations—Outdoor Alliance, Outdoor Recreation Roundtable, Surfrider, The Mountaineers, IMBA, Outdoor Industry Association, organizations representing hunting and fishing interests and RV interests, and many, many more orgs, all working simultaneously in an effort to see this historic recreation bill package passed.

Our small team focused a lot of effort on speaking with the bipartisan group of 16 senators that submitted a joint letter to the Secretaries of Agriculture and the Interior expressing the appropriateness of fixed anchors in Wilderness and wanting a report on the status of the agencies’ respective proposed fixed anchor regulations. The Protecting America’s Rock Climbing (PARC) Act, a component of the EXPLORE Act that serves to recognize recreational climbing (including the use, placement, and maintenance of fixed anchors) as an appropriate use within the National Wilderness Preservation System, further emphasized the intent of those senators, and of Congress more broadly, to preserve the historical and well-precedented practice of fixed anchor utilization in Wilderness.

Scene 2

It is no secret that the waning days of the 118th Congress were fairly chaotic. Characterized by the forthcoming change of administrations, few clear “unified” priorities, and the pending departure of several longtime members of Congress, the landscape was hard to navigate. We left DC understanding the potential pathways to passage of EXPLORE, but still not certain which vehicle would get it across the finish line. The following week we saw it miss the cut for the NDAA Manager’s Amendment and concentrated on advocating for its inclusion in the CR. As the days drew closer to a potential government shutdown, we came to understand that the CR was likely going to be relatively tight compared to previous iterations, and would probably not allow for bills such as EXPLORE to ride on it. The CR was out for us. That is when we heard that Senator Joe Manchin (I-WV) was considering introducing EXPLORE as a stand-alone bill.

Photo by AAC member Kennedy Carey.

This was INCREDIBLE news. However, we had some concerns as we knew that the Senate was working off of the House-passed version, which had been passed via unanimous consent (UC) in April of 2024, stewarded by Rep. Bruce Westerman (R-AR). We understood that the Senate wanted the House to address some issues in the bill, but that would require the bill to be sent back to the House for consideration and a vote...which would require time. And there wasn’t any.

On the morning of December 19, we heard that Senator Manchin was planning to introduce the House version of EXPLORE on the Senate floor for a UC vote. For those tuning into the live broadcast, we had no idea what time the possible introduction would occur. It was observable that Senator Manchin was talking to a group of senators and then left the floor. A few hours later Senator Manchin appeared and presented the EXPLORE Act for consideration via a UC vote. During his introduction, he emphasized that the EXPLORE Act was “...something that we all agree on” and that “the House and Senate are in agreement,” and that there were some changes that needed to be made but could be accomplished during the next Congress. Now keep in mind, in order to pass via UC there cannot be a single vote of dissent.

Scene 3

After Senator Manchin teed the bill up for a vote, Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) stepped up to the podium. He began by reserving his right to object until the end of his speech. This is to say that no one knew whether he would be objecting and opposing the UC of EXPLORE or allowing it to pass. He spoke to his TAKE IT DOWN Act, which is a bill seeking to protect victims of deepfake pornography. The years of work on all the bills associated with EXPLORE hung in the balance—all the work on SOAR, BOLT, VIP, and Recreation Not Red Tape, on the precipice of passage. You can imagine all the breaths that were being held while Senator Cruz spoke.

“I do not object.”

Those words, spoken as a favor to retiring Senator Manchin and Rep. Westerman, provided true theater drama that we are generally accustomed to watching in a much different environment. The historic EXPLORE Act was passed, via unanimous consent through the Senate, and was on its way to the president. On January 4, 2025, President Biden signed the EXPLORE Act into law, and it became Public Law Number 118-234.

Act 1, Scene 3, complete.

Act 2

As EXPLORE was being teed up for a vote in the Senate, the National Park Service quietly announced that it was withdrawing its proposed fixed anchor guidance. This gesture suggests a new window of opportunity for climbing organizations, as well as other interested recreation and search and rescue organizations, to work in collaboration with land agencies to develop sound fixed anchor policies that reflect the direction of Congress and their passing of the PARC Act.

The AAC Policy Team and the Executive Director have visited DC over the last two months, working carefully with our partner organizations in these quickly evolving times to support the implementation of EXPLORE, discuss impacts on our public lands as a result of the federal reductions in force, and address other issues.

Stay tuned on the AAC’s digital platforms to learn more about the status of public lands policies, and how they impact, or may impact, climbers.