A collection of old and rusty hardware to be replaced at Sandrock, Alabama. Land of the Cherokee and Yuchi people. AAC member Caleb Timmerman.

A Little Rust is All It Takes

By Stephen Gladieux, AAC delegate to the UIAA Safety Commision

Consider the following true story:

It’s the mid-2000s and two friends are on a long, multi-pitch sport climb. They’re excited—it is the climbing vacation to paradise they’ve dreamt about. They’ve been on clean, hard limestone all week. They’re prepared and plenty experienced for this climb.

The leader has reached a belay stance and is getting ready to bring up their partner. They are building an anchor on two shiny new bolts. As the leader flakes the rope, they see the first bolt on the next pitch is close, and they decide to clip the rope into it—giving their partner a little more of a top-rope in the last moves and setting them up for swinging into the next pitch. The follower gets to the anchor and clips in. What a climb! They both lean back to laugh.

Both anchor bolts break. They fall.

Only that extra bolt on the next pitch holds, keeping them from dying, but all three bolts were shiny and brand new.

Corrosion isn’t always visible, and there are a few different kinds of severe corrosion that result in scary failures like the one described above. These have been known for a long time in industries like construction and nuclear power, but it has only been in the last 20 years or so that we’ve recognized them in climbing anchors. These failures don’t require a lot of corrosion, just a very small amount. The two main types are Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) and Sulfur Stress Cracking (SSC), but there are others as well. For a number of reasons, these are really terrifying problems in climbing safety: they can happen very quickly without any easy-to- spot outward signs; they are difficult to predict; and they happen on stainless steels that climbers and route developers commonly think of as bomber. Like in any other part of climbing, assumptions can kill.

Starting in the late 1990s, climbers started talking about this issue. The problem seemed particularly obvious in coastal climbing areas, but it began to crop up elsewhere as well. Companies were quietly adjusting the alloying content of their wedge bolts, scientific papers were being written, and developers were beginning to use glue-ins and titanium. And ultimately, the Union Internationale des Associations d’Alpinisme (UIAA) Safety Commission (SafeComm) started looking into the issue in a rigorous way.

The UIAA is where the buck stops with global climbing safety. It is a union of climbing federations from 73 countries that works on things like mountain medicine, protecting climbing areas globally, organizing Ice Climbing World Cups, and standardizing training curricula and safe practices. It is where gear failure from all countries gets analyzed. It is where climbers, manufacturers, and labs come together to make climbing safer. As the national organization for climbers in America, the American Alpine Club is the U.S. representative to the UIAA.

To address the SCC issue, the SafeComm worked for almost 15 years to develop a new Rock Anchor Standard that tests the complete anchor—UIAA123. In the summer of 2025, we updated it at our 50th anniversary meeting with guidance on welding.

How Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) Works

SCC starts with a pit on the surface of the material. This could be a small defect in the steel, damage caused by placing the bolt, or something left over from manufacturing. Pitting corrosion can also start the process. Pitting corrosion causes deepening pits to form in the surface and is typically fueled by the presence of chlorine. In all these types of corrosion, chlorine isn’t consumed, it is just something that facilitates the corrosion’s progress. That means it doesn’t take very much to make this happen—a high concentration, but not a large amount.

Once there is a deep enough pit, the process changes—in some cases it will stop here, but in others, the corrosion will develop into SCC and a crack will begin to extend from the bottom of the pit. This crack drives forward through the shaft of the bolt via a complex mechanism that doesn’t cause the outside of the bolt to corrode. In a short time, the bolt could break with body weight but show little sign of this danger.

Sulfur Stress Cracking (SSC) is similar in effect, but not in process. For now, we’ll focus on SCC.

Stress Corrosion Cracking requires three things: a susceptible material, a suitable environment, and sufficient stress in the material. None of these things are quite as straight-forward as they seem and the rate of cracking can vary from a few months to several years. However, solutions exist to keep our community safe.

Rethinking Susceptible Materials

Photo by AAC member Caleb Timmerman.

There are hundreds of alloys of stainless steel. Climbers have historically only used a few. These historically-used alloys tend to be more susceptible to SCC than zinc plated low carbon steel. There is a spectrum of resistance to SCC. The resistance of a material comes from more than just its chemical composition: It is influenced by its microstructure, and this is controlled by how it was manufactured.

The thermal history of a bolt—how it was heated and cooled—can have a particularly large effect on its resistance. In fact, a relatively resistant material can be made extremely susceptible to SCC through its manufacturing process. This is one reason why any welding in bolts or anchor rings and chains can be dangerous if not well controlled. It is not just about the type of steel alone.

Acknowledging the Environments That Facilitate SCC

The environments that cause SCC aren’t all that exotic. We’ve seen it in some places more than others, but the ingredients can be found at many crags. Only a small amount of chlorine is required. The presence of sulfur helps. Calcium can make both worse. Concentration right at the bolt is what matters, not how much there is in general.

These elements are not rare. Calcium is in many of the rocks we climb, not only limestone and dolomite. Sulfur can come from many sources: In the Pacific we see underwater volcanoes vent into the water; in swathes of the U.S., coal power plants create plumes of sulfur that drift eastward. Sulfur-reducing bacteria in the soils above our climbs convert it to a form that is more dangerous. Chlorine can come from seawater and spray hundreds of kilometers inland. It can come from road salt. It is in our sweat and in rocks and lakes.

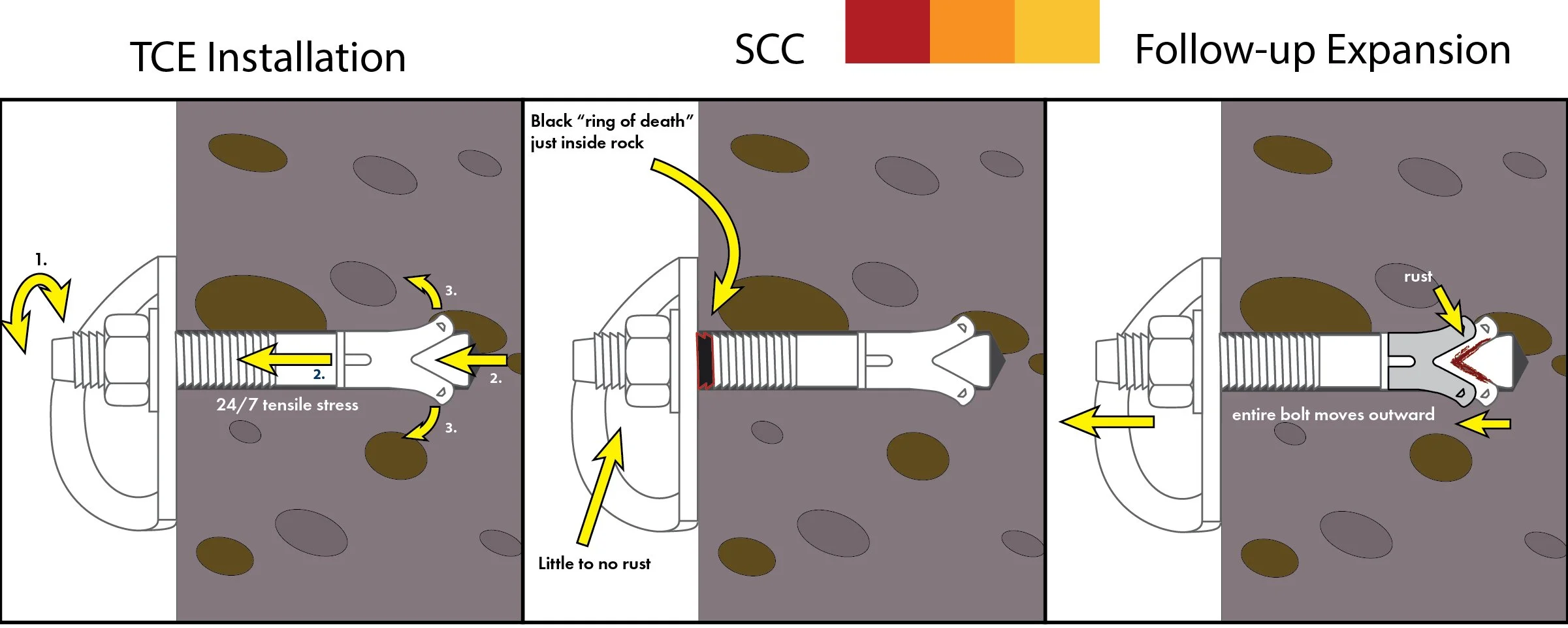

TCE Installation steps: 1) the nut or bolt is turned to a specified maximum torque based on the shear strength of the bolt; 2) the shaft is pulled out of the hole; 3) friction between the rock and the collar keeps it in place, which causes expansion as the wedge on the shaft moves through it. As the wedge meets more and more resistance to pulling out, tensile stress is generated in the shaft which will be there from now on. Tension in the bolt shaft can be a factor that contributes to Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC), as described on page 20. The second illustration above illustrates how hard it is to detect SCC. The third illustration shows how a small amount of corrosion in the expansion components of a TCE can lead to the bolt slowly moving out of the bolt hole instead of expanding more, even without SCC developing. Illustration by AAC member Stephen Gladiuex.

Understanding Stress Created by Bolt Type

Most of the fixed anchors we use are torque controlled expansion anchors (TCEs). This includes wedge bolts and sleeve bolts like the five-piece as well. Think of them as small machines that are part of the safety system. When the nut or bolt in these machines is turned, it creates tension in the shaft—when the shaft is pulled out by this tension, and the collar/sleeve stays put, it results in expansion at the back of the hole. There is no way to avoid this stress—it is inherent to the design of the bolt. This stress is there day and night. In this kind of bolt, that inherent stress allows SCC to form cracks across the shaft.

And even without SCC, and instead with the littlest bit of rust, these bolts can become ticking time bombs.

When the bolt was brand new, there was less friction between the wedge and the collar than there was between the collar and the rock. When it was initially tightened, this friction caused the collar to stay put—and instead the wedge moved and the bolt expanded. But with only six months and a winter, and the environment found at any crag in the U.S., now there is a little corrosion between the wedge and the collar.

When that first big fall happens, the wedge could expand just a little more, the machine would work, and the bolt could be stronger. The climber would see a spinning hanger, but after tightening it, the bolt wouldn’t move again until a bigger fall happened, which might never happen. It was able to have follow-up expansion because the machine in the back of the hole still worked.

In a different scenario, both the wedge and the collar could move out together, because they are stuck together due to just a little rust. The climber still sees a spinning hanger and still tightens it—but the bolt doesn’t expand more, it just moves out of the hole. It will keep pulling out, little by little, and keep getting weaker. Depending on the type of bolt, you may never know.

Different bolt types are also made differently. Any time metal is bent or reduced in size by a process called rolling, there are residual stresses in the material. Hangers and glue-ins exhibit these kinds of residual stresses, but they tend to be lower in magnitude, and that’s good. It is one of the reasons glue-in anchors are a better choice for corrosion. It would be possible to almost eliminate these residual stresses with an annealing heat treatment, but this would add cost.

If a good resin is used for a glue-in anchor, the bolts also get the added benefit of having the metal shaft insulated from contact with compounds in the rock or its surface.

All of this combines to make SCC difficult to predict, and especially difficult to estimate how long it will take to render a bolt unsafe. Often, the only sign that’s visible is a slight black ring around the shaft just at or inside the rock. It is tough to predict, it is tough to inspect, and it can kill.

UIAA123—Not as Simple as 1, 2, 3

In order to have confidence in our fixed anchors, we need to evaluate the entire bolt/ hanger/chain assembly, and its installation process as well. We need to pair these anchors with a crag environment that they can handle. The UIAA 2020 Rock Anchor Standard Update included testing the complete anchors and classifying them.

A lot of work went into figuring out the line between different environments, and how to test them in a repeatable way. You can now find bolts, hangers, and complete top anchors on the market that are certified to the UIAA Standard from a number of major brands such as Lappas, Fixe, AustriAlpin, Team Tough, and Climbing Bolt Supplies. Lappas and Fixe have anchors that have been certified at the SCC level as well.

In the spring of 2025 we met with bolt and anchor manufacturers and introduced a requirement to improve welding quality. This most commonly affects welded top anchor rings and chains, but also glue-ins where the ring is welded. Manufacturers are now required to follow welding industry standard quality controls. These standards ensure that welds are executed with the precision and quality needed to maintain the safety, reliability, and durability of the anchors. Most importantly, this will prevent any welds from being a sort of Achilles heel that cracks quickly in an otherwise safe anchor.

So now, with a classification of anchors and with tests, we’ll be safe, right? Not yet—there is more to do. We need to understand our crag environment in order to select the right bolt. It can vary pretty dramatically from route to route, and even bolt to bolt on a route. The classification must be sufficient for the whole route, and preferably the whole crag. One of the next projects we are working on at the UIAA is to improve the maps of corrosion risk and pin them with specific knowledge of crags and crag chemistry so that there can be better guidance for land managers and those placing bolts.

Next Steps

Recently at the UIAA SafeComm, we received a request from the town of Kalymnos, an iconic climbing area in Greece. They have many routes that are suffering from corroded anchors. Climbers have become an important part of the local economy, and Kalymnos has gotten a large grant to rebolt routes—but they don’t know whom to trust with this important task, or how it should be done. Not every climbing area is fortunate enough to have a great local climbing organization that is skilled in route maintenance.

At the UIAA we’re pivoting again to help solve this challenge. We’re beginning work on the idea of a rebolting certification course that will include feedback from all over the world to gather the best techniques. Pooling knowledge and techniques globally will pay off in making climbers and routes safer everywhere. It will also mean that land managers will have something to look toward when they are not sure whom to trust with the lives of people climbing, or with the conservation of crags.

The UIAA has been around since the early 1930s. We just hit the 75th anniversary of our first rope safety standard, and the 50th anniversary of the Safety Commission. In those years we’ve moved from climbers not knowing which ropes they could trust with their lives, which carabiners and helmets to use, to having gear so clearly marked and reliable that most climbers don’t think about it. With the new welding update to our Rock Anchor Standard, we are working toward the day that each fall on a bolt—no matter where you are in the world—can be infused with just as much trust.

About the Author

Stephen Gladieux has been the AAC delegate to the UIAA Safety Commission since 2020, and was a corresponding member and consulting expert since 2012. He’s been climbing for 31 years, and he holds a degree in materials science and engineering, as well as one in French literature from the University of Michigan. He does about half of his climbing underground and sees bolt failure all over (and under) the world. Stephen lives outside Portland, Oregon.