Findings from the AAC Research Grant

by Hannah Provost

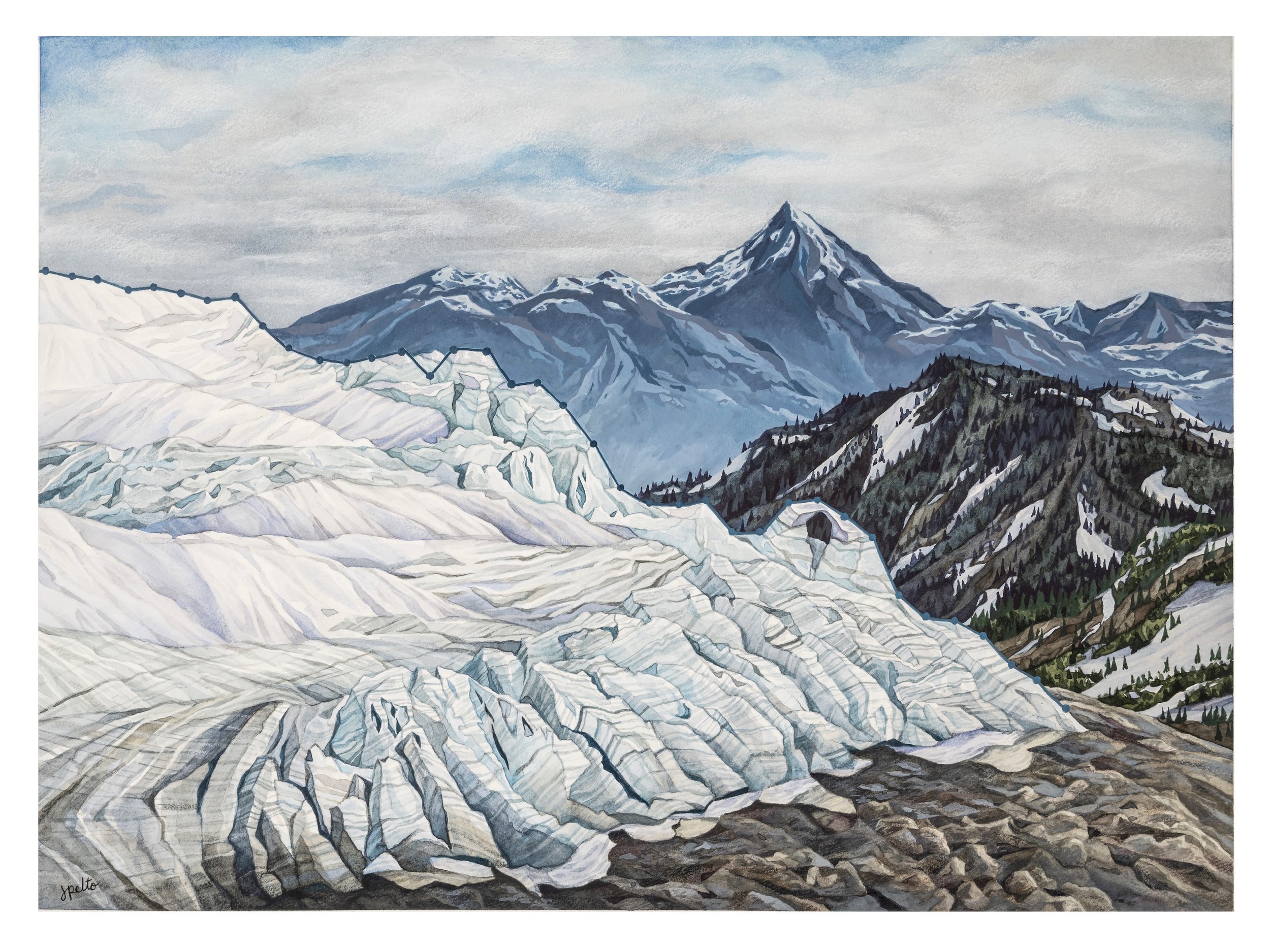

Artwork By Jill Pelto

Originally published in Guidebook XIII

Eric Gilbertson was on the summit of Rainier. Or was he? With the differential GPS set up in front of him, he hopped from foot to foot—it was cold up there, but he was also anxious to confirm his suspicions by applying a more rigorous measuring process to the changes he could see with the naked eye. Funded by the AAC Research Grant, he had used an Abney level to measure the relative heights of Columbia Crest, the traditional icecap summit of Rainier where he stood now, as compared to the actual highest point in the summit area—the southwest edge of the crater rim, which was a rock outcrop.

Based on the Abney level, Columbia Crest was distinctly shorter than the southwest rim. With calculations spinning in his head, he noticed the unmistakably dirtier, more trampled quality of Columbia Crest, the way dirt and rocks seemed to muddle the pure snow dome, bringing a wilted quality to the landscape, especially compared to what he could remember seeing in old photographs of Rainier’s summit. He would have to wait to process the data from the differential GPS to be sure exactly by how much the summit had changed. Yet more than the relief of seeing his hypothesis likely confirmed, a bigger question loomed: Were mountains, which so many consider the stalwart indicator of the unmoving, the unchanging, the steady, actually shrinking? And what would it mean if they were?

Eric Gilbertson is a man of many lists and projects. Each of his projects coalesces around peakbagging, and now surveying. The idea to research the current heights of the five remaining icecap peaks in the Lower 48, which includes Rainier, started when Mt. St. Helens eroded off the top 100 highest peaks of Washington list. Gilbertson had discovered that St. Helens had been steadily eroding by four inches each year since 1989, and because of that, St. Helens had technically fallen off the top 100 list around 2021. As an exacting, rigorous person who prizes accuracy above all in his life’s work, Gilbertson was intrigued—were there more discrepancy in the heights of the other top 100 Washington mountains? If his goal was to do all the hundred highest, and be the first to do them all in winter no less, he wanted to do it right.

Before fact-checking the hundred highest list, before measuring the status of the five historical icecap peaks of the Lower 48, Eric and his brother Matthew had been pursuing what they called “The Country High Points Project.” Though the brothers are each respected alpinists in their own right, with several technical first ascents and inclusions in the American Alpine Journal to Eric’s name, they are peakbaggers at heart. Which is why they conceived of the project to get to the highest point of every country in the world, as defined by UN members and observer states, plus Antarctica. Thus, there are 196 highpoints on their list. So far, Eric has gotten to the highest point of 144 countries and Matthew has ticked 97.

Eric says he sees the project as a framework for creating opportunities for really interesting adventures. “[It] kind of requires every kind of skill set you can imagine. It definitely requires high-altitude mountaineering, like K2 is on there and Everest, but it also requires jungle bushwhacking in the Caribbean or hiking through the desert in Chad. There is so much red tape you have to get through—like in West Africa there are so many police checkpoints so you have to navigate those—so many languages you have to speak, logistics to make it interesting, and the other interesting aspect is [sometimes we don’t know which] is the highest mountain, so in comes the survey equipment.”

Decrease in Glacier Mass Balance, by artist Jill Pelto, the daughter of glaciologist Dr. Mauri Pelto. Jill Pelto integrates scientific data into her artwork to capture the impacts of climate change on our wild landscapes.

When, in 2018, the brothers determined the highest point in Saudi Arabia had actually been misunderstood all along, Eric became particularly interested in exactness and discovery, and how these elements added an interesting complexity to getting to the great heights of the world. A lot more was unknown than one might first imagine, given our information-overload culture. Not knowing if the mountain you were climbing was even the highest point in the country added a challenge that seemed to surpass even first ascenting.

Yet Eric is not always flitting across to the farthest reaches of the world. As an associate teaching professor at Seattle University, he is rooted a good portion of the year, so he is constantly finding ways to feed his passion for discovery and peakbagging right in his backyard. First with adjusting the accuracy of the hundred highest list, and then with his research on icecap peaks, Eric had discovered that even in one of the most mapped countries in the world, a lot more was unknown, and even the known was changing.

There have been five icecap peaks in the Lower 48 in the last century, according to the collective mountaineering knowledge that Eric Gilbertson consulted: Mt. Rainier, Eldorado Peak, East Fury, Liberty Cap, and Colfax Peak—all in Washington state. According to Eric’s research, Mt. Baker has had a rock summit since the 1930s, and therefore was no longer on the list for consideration. For Eric’s purposes, an icecap peak has permanent ice or snow on its summit throughout the year, never melting down to rock. Until now, glaciologists and others studying the cryosphere, or Earth’s ice in all its forms, have not agreed upon a specific term for mountains with snow or ice at their summits, though the term “icecap summit” or “icecap peak” has been used colloquially throughout the world. Eric’s findings—that these summits are dramatically changing— have brought a new importance to being able to name and articulate what exactly is happening on the world’s icy summits.

Support Our Work— And Get The Guidebook Mailed to You!

Each membership is critical to the AAC’s work: advocating for climbing access and natural landscapes, offering essential knowledge to the climbing community through our accident analysis and documentation of cutting edge climbing, and supporting our members with our rescue benefit, discounts, grants and more. Plus, as a member, you’ll get the print edition of our quarterly Guidebook, telling fascinating climbing stories like this!

Though the scientific importance of icecap peaks has been largely understudied until now, the cultural importance of mountains covered in ice has been profound for climbers and mountaineers. In the past, combatting snow and ice when climbing was a prized indicator of skill and proficiency, a symbol of a “true” alpinist or climber. In fact, when the AAC still required applications for membership, a memo from the 1926 bylaws indicated that the requirement for membership hinged upon “not the mere attainment of height by walking, but rather the ascent of peaks or the traverse of passes and glaciers well above the snowline of the district and presenting technical difficulties.” Mark Carey, a multidisciplinary researcher who studies the societal dimensions of climate change, has illuminated the current fascination with and fixation on glaciers in our current discussions about climate. He argues that glaciers have become prominent as climate imagery not because of the “specific consequences of melting glaciers or the scientific data emerging from ice cores,” but rather because glaciers have many cultural associations that they have gained over the centuries, which have multiplied their significance. Glaciers have been variously seen as terrifying and vast, gorgeous and mysterious, as hubs for science, as important challenges of mountaineering, as something to conquer, and as a symbol of wilderness. Though not glaciers properly, these same cultural touch points seem to apply to icecap summits. More was at stake in Eric’s research than just changing a few numbers on a map.

The AAC Research Grant set Eric up to do a rigorous exploration into this question. Eric used both a differential GPS and an Abney level, and also cross-referenced all historical data he could find about the elevations of these peaks. In surveys done in 1956 using a theodolite and an Abney level, and in 1988 and 1998 using a differential GPS, Rainier’s height was found to be basically the same. Eric’s 2024 measurements were conducted in a way that created methodological consistency with these previous surveys. Eric found that four of the five historical icecap peaks have melted by 20–30 feet in the last 20–70 years, and that three of the five are in fact no longer icecap peaks, because they no longer have permanent ice on their summits. As Eric reported: “Mt Rainier melted 21.8ft, Eldorado Peak melted 20ft, and East Fury melted 30ft. All three now have rock summits. Liberty Cap melted 26.3ft but is still an icecap peak. Colfax is maintaining a steady elevation and is still an icecap peak.” After the relief of being right came the sense of loss.

Rainier had shrunk. This iconic mountain is melting. It seems a devastating revelation, and not just to climbers. It might even be a more tangible and understandable visual than the far more obscure and far-away-feeling imagery of glaciers retreating in the Arctic and polar bears stranded on collapsing sea ice. And then, of course, there is also the totality of realizing that four of the five historical icecap peaks have all shrunk, and by similar amounts. Now, Eric feels driven to dig into the much more complicated question of why.

40 Years in the north Cascades. The top surface of the mountain glacier is a line graph that depicts the decreasing mass balance of North Cascade glaciers in Washington state from 1984-2022. By Jill Pelto

According to Dr. Mauri Pelto, a glaciologist of four decades and the Director of the North Cascade Glacier Climate Project, Eric’s findings are consistent with the melting found across monitored glaciers in the region: “Global warming has caused the widespread thinning of mountain glaciers, including at their highest elevations, not just here [in the Cascades], but across all mountain ranges. Cascade summits are locations where the wind limits the deposition of snow, making the few remaining icy locations vulnerable to increased summer melting. In the North Cascades we have observed an annual ~1% volume loss over 41 years. This melt has caused glacier retreat, but also has been exposing new rock areas all the way to the top of the glaciers.”

The fact that these very visible parts of the cryosphere are dramatically changing is also not surprising when contextualized by the grand scope of climate research. According to the National Snow and Ice Data Center, “the cryosphere is an especially sensitive indicator of climate change. ... Between 1979 and 2016, Earth lost 87,000 square kilometers (33,000 square miles) of sea ice, an area about the size of Lake Superior, per year on average. The extent of the cryosphere matters because its bright white surface reflects sunlight, cooling the planet. Changes in the area and location of snow and ice can alter air temperatures, change sea levels, and even affect ocean currents worldwide.” Even though the sheer volume of ice lost on Rainier and the other three previously icecap summits seems inconsequential in comparison to this average worldwide sea ice loss, it means that the impacts that glaciologists have been seeing across the world are a little closer to home than we might like to believe. In the grand scheme of climate science, the summits of these peaks might only be unique to a climber’s mind.

For many experts in this field, Eric’s findings ring true on an intuitive level. But to drill down even more specifically on the mechanism behind Eric’s findings, Eric has teamed up with Dr. Scott Hotaling, a specialist on high mountain ecosystems and how these ecosystems are being affected by climate change, and together they are working on an academic paper that will pair temperature data with Eric’s elevation surveys. Perhaps this paper will explain the tantalizing question of why Colfax Peak is an outlier.

Of course, as devastating and evocative an image as it might be, there are also political and legal implications to changing those tiny numbers etched next to the summits on your map. National parks, including Rainier, are beholden to USGS topographical surveys for the elevations they report. Eric’s findings are essentially moot in the eyes of the NPS until the USGS replicates them. But as Mike Tischler, the Director of the USGS National Geospatial Program, has reported, the USGS does not currently collect or maintain point elevations of summits.

Tischler reports: “Historically, point elevations of prominent peaks were printed on topographic maps, with the source of the elevation being manual survey. The most recent USGS example of this is a 1996 update of a topographic map originally produced in 1971, based on a field verification in 1971.” Though the USGS is actively conducting surveys using lidar technology to offer 3D elevation data for the U.S. topography, a specific spot elevation value is not official, nor does it represent a precisely measured value for something like a summit. As the USGS warns on their website, the data found by this method might not be the most accurate for alpine landscapes, as “differences between these elevations [manually surveyed elevations vs. lidar data] might exist for features such as mountain peaks or summits, and where the local relief is significant.”

And who would expect mountains to change heights anyway, even if most alpinists know that the mountains seem alive? For now, the USGS seems uninterested in verifying Eric’s findings. But even with this challenge making it difficult for Eric’s research to be widely implemented, Eric is unfazed. This hiccup is just another logistical challenge to navigate as he seeks, with absolute determination, exactness in his climbing goals. Certainly, whatever his next project, Eric Gilbertson will be shaking things up a bit and challenging what climbers, and everyone, knew about the height of mountains.