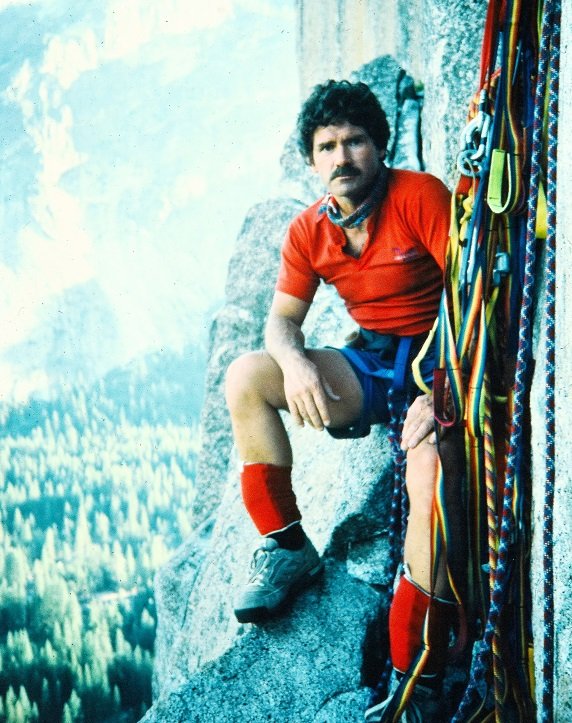

Nico Favresse, Yosemite, US, Alien Finish 12b, Rostrum. PC: Jan Novak.

Climbers and other visitors who plan on entering Yosemite National Park between 6 a.m. and 2 p.m. from June 15 thru August 15, 2025, or during Memorial and Labor Day weekends, will require reservations. Visitors holding a Half Dome or wilderness permit, in-park camping or lodging reservations, or entering on a regional or tour bus will be exempt from reservation requirements. Reservations will be available on Recreation.gov beginning on May 6, 2025 at 8 a.m. PDT, with additional reservations becoming available 7 days prior to any arrival date. Reservations will cost $2, and each visitor will be allowed to make two entry reservations per three-day period.

Yosemite's iconic granite walls draw climbers, hikers, and outdoor recreationists from all over the world. Big wall climbers spend long days on El Cap and Half Dome above the valley floor, attempting free ascents or classic aid climbs. Due to the park's growing popularity, reservations and permit systems have been implemented. Climbing is no exception.

In 2021, Yosemite NPS began a two-year big wall permit system pilot program in hopes it would help climbing rangers understand patterns on the wall and minimize negative impacts on the landscape through education. In January 2023, the permit program became permanent, and now all climbers staying overnight on big walls are required to have a permit.

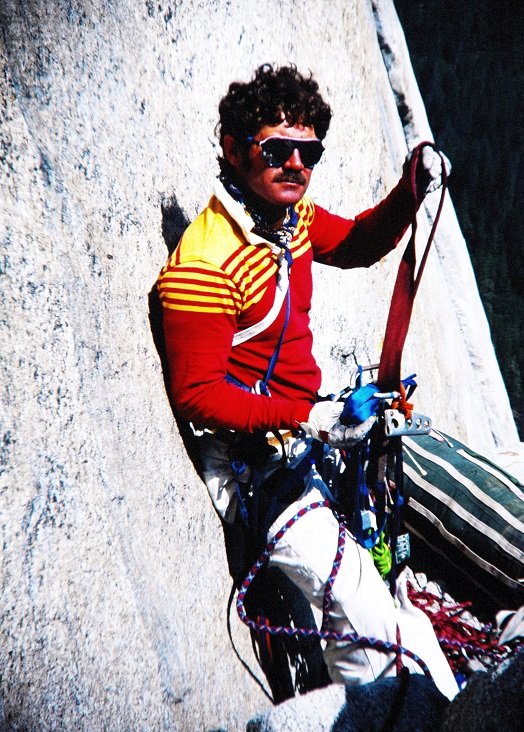

PC: Andrew Burr

As with everything in the climbing community, there has been a lot of discourse surrounding this, as seen on Reddit and Mountain Project threads over the past couple of years. Climbers speculated: Would the rangers be enforcing a quota? Would these permits be available 24/7, or would reservations need to be made in advance? Would climbers have to use the dreaded recreation.gov?

Through the permit system, big wall permits are free and available for climbers to self-register 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, near the El Capitan Bridge at a kiosk near the food lockers. There is no quota for routes.

In addition to timed permits, during peak hours (6 a.m. and 2 p.m. on Memorial Day weekend, any day between June 15 and August 15, or Labor Day weekend), climbers must make reservations to enter the park. This is a timed entry reservation that is also used at other parks, such as Zion National Park, Rocky Mountain National Park, and Arches National Park, allowing the park to regulate the influx of visitors.

There is no formal check-in with the rangers after climbing (or bailing). Yosemite climbing rangers and stewards use the information they gather from the permit system to update an Instagram account that reports on big wall traffic. The Instagram's daily posts include information for the number of people on popular climbs like Freerider/Salathe, Zodiac, and Regular Northwest Face of Half Dome.

"It is a work in progress, but we are trying to find a sustainable way to get that information out to climbers so that people can disperse from crowded routes if they want," said Yosemite Climbing Ranger Cameron King. The feedback the rangers have received on the account has been positive.

Below, we've created a guide to help you navigate your next Yosemite trip filled with all the fine print and details to minimize route finding off the wall.

How To Climb a Big Wall in Yosemite: A Checklist

PC: Andrew Burr.

How to Get Your Wilderness Big Wall Climbing Permit

Permits are free, and there is no quota. Climbers can self-register 24 hours per day, 7 days per week, at a kiosk near the food lockers near El Capitan Bridge.

You can pick up your permit the day before or the day of the start of your overnight climb. This allows for more in-person education opportunities but doesn't limit climbers to "office hours."

Up to eight people can be on a wilderness climbing permit.

There is some flexibility, so you're not locked in! If the trip leader, formation, route, and dates remain the same, and the maximum number of people specified on the permit is not exceeded, things can change last minute.

If the number of people on the permit changes, the trip leader is not required to change the permit, and it will still be valid.

The permit system is not held to a quota, so there is no need to fill out the permit for the maximum number of people if you are unsure about the number of climbers in your party. The rangers encourage folks to be as accurate as possible when filling out the permit.

You don't want to miss this: Climbers with a Wilderness Climbing Permit are eligible to spend one night before and one night after an overnight climb in an open backpacker's campground.

The cost is $8 per night (per person); reservations are not required.

Tent camping only, no sleeping in your car.

For 2025, White Wolf campground is closed, and Tuolumne Meadows is set to open in August.

The Fine Print from Yosemite NPS:

Except for the base of Half Dome, camping at the base of any Yosemite Valley Wall is prohibited. Camping on top of Half Dome is also prohibited. You must be at least one topo pitch above ground level before you can bivouac on the wall.

When camping in legal areas or at the base or summit of walls, select previously impacted sites or durable surfaces. Trampling vegetation is prohibited.

Fires are prohibited at the summit and base areas of all Yosemite Valley Walls (Half Dome, El Capitan, Washington Column, etc.)

Packing out your solid human waste from the wall is required. You must have an adequate container to carry your human waste from the wall. Once you have finished, you cannot leave your human waste (or container) unattended—dispose of waste properly in dumpsters (wag bags, etc.) or pit toilets (paper/waste only). Consider packing out urine from popular routes/bivy sites as well.

Carry out all trash. Water bottles are considered trash if left behind.

Proper food storage is mandatory. All food must be hung on the wall at least 50 feet above the base of the route in 5th class terrain (or Aid). Do not leave food unattended while shuttling loads for your climb. On the summit of walls, you can either: 1) Store your food in a bear resistant canister or 2.) Hang food at least 50 feet over the edge. Do not hang your food in trees. Report any bear incidents to the nearest ranger or by calling 209.372.0322.

You are not permitted to leave ropes unattended for over 24 hours. If you are "working" a route, remove ropes after you are finished for the day. Be considerate of other climbers, and refrain from fixing lines on popular routes. All fixed ropes and caches must be labeled with name, date, and contact information, and will be removed if left unlabeled or abandoned.

The use or possession of a motorized drill is prohibited.

The Iconic Camp Four and Other Camping Options:

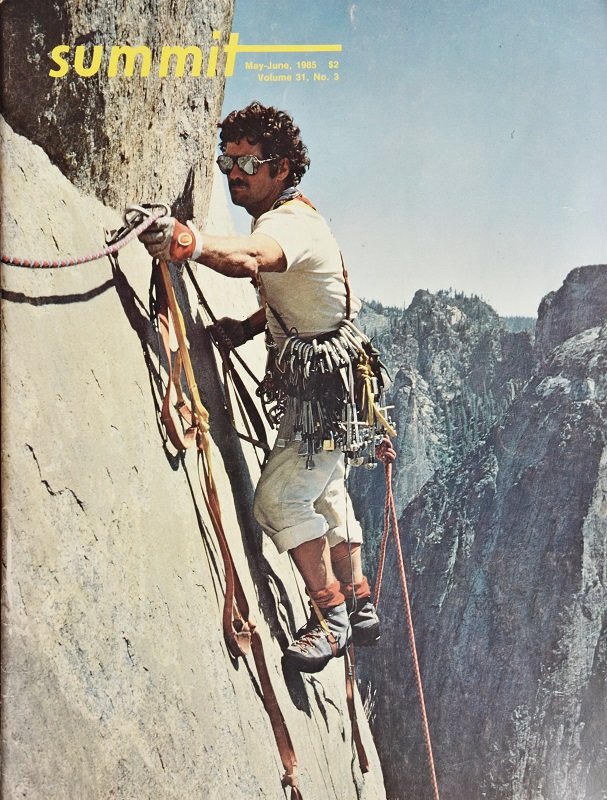

Nick Sullens, and Will Barnes, lat minute prep before heading to the Captain., Yosemite NP. PC: Jeremiah Watt.

To stay at Camp Four during peak season, make a reservation: https://www.recreation.gov/camping/campgrounds/10004152

Outside of peak season (October 28, 2024 - April 14, 2025), the campground is first-come, first-serve.

You don't want to miss this: Climbers with a Wilderness Climbing Permit are eligible to spend one night before and one night after an overnight climb in an open backpacker's campground.

The cost is $8 per night (per person); reservations are not required.

Tent camping only, no sleeping in your car.

For 2025, White Wolf campground is closed, and Tuolumne Meadows is set to open in August.

In a calendar year, people can only stay for 30 nights in Yosemite National Park. From May 1 to September 15, the camping limit is 14 nights, and only seven nights can be in Yosemite Valley or Wawona.

AAC Inspiration:

From the AAC Library

Guidebooks:

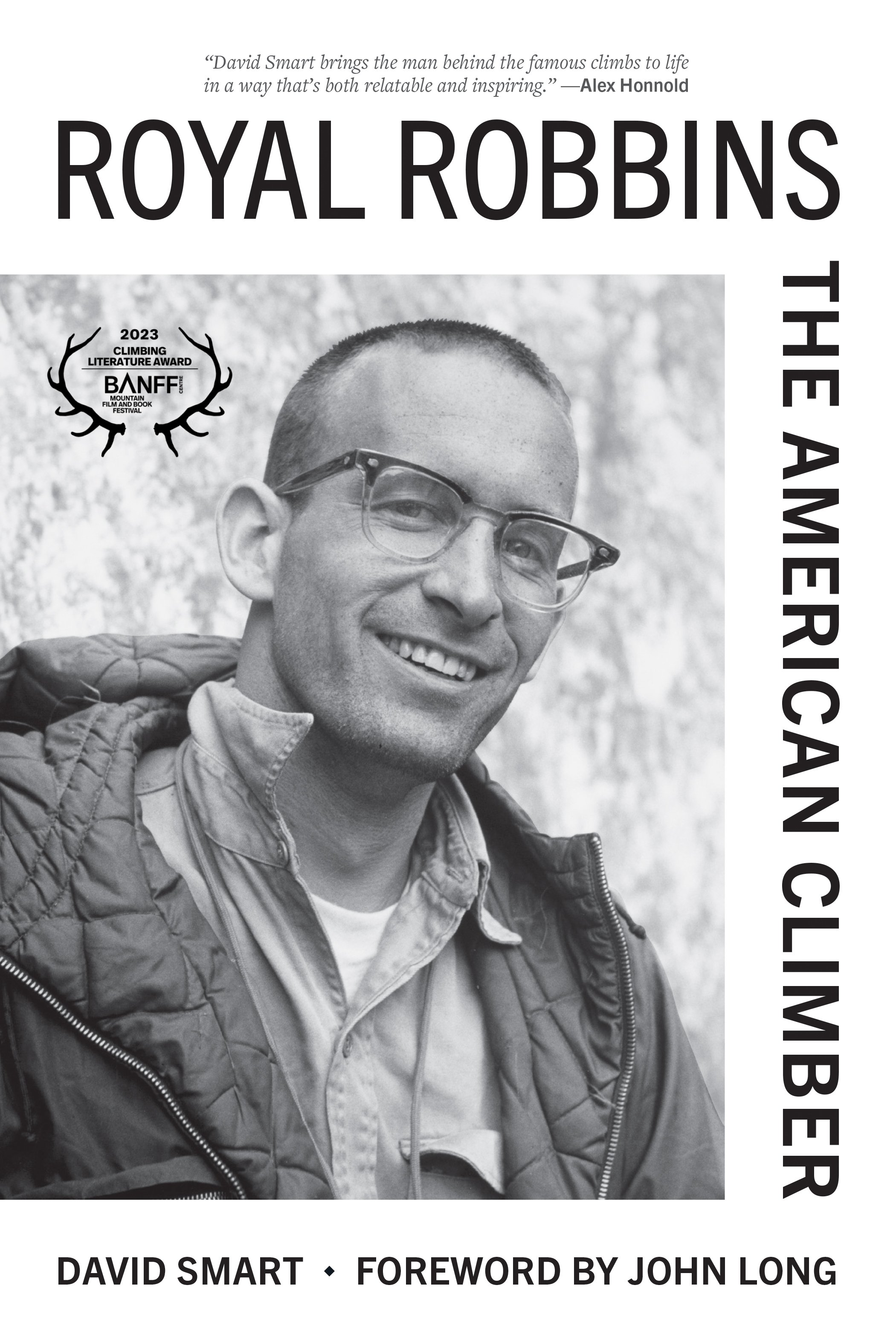

To Stoke the Upcoming Adventure:

According to the National Park Service, more than 100 accidents occur in the park each year. Here are some select accidents to avoid from Accidents in North American Climbing:

AAC Podcasts for the Road Trip:

PROTECT: Amity Warme and a YOSAR Climbing Ranger Weigh In on The Yosemite Credo

CLIMB: Babsi Zangerl’s Secret to Her Exceptional Yosemite Resume

EDUCATE: Hazel Findlay on Yosemite, Magic Line, and the Theory of Flow

The Climber's Credo aims to provide the Yosemite climbing community and land managers with a tool to promote Yosemite's minimum-impact climbing ethics to protect the park's Wilderness and climbing culture.

Further questions?

PC: Andrew Burr

Find information on current conditions throughout the park here, and the forecast updated here.

Call a climbing ranger at (209) 354-2025 or email a ranger through the contact us form.

During the busy season, climbing rangers are available at the Ask-A-Ranger climber program at El Capitan Bridge from 12:30 p.m. to 4:30 p.m. for more in-depth big wall leave no trace and climbing technique advice, safety tips, and route condition information.

Looking for daily updates on Yosemite's big wall traffic?