The following report will appear in the 2023 edition of Accidents in North American Climbing. You can purchase the 2022 book and many previous editions through the AAC Store.

Free Solo Fall

Southern California, El Cajon Mountain, The Wedge

El Cajon Mountain, seen here, was scene of a recent free solo fatality. The route in question is Leonids, which climbs the face to the left of the angling dihedral and the sun-shade line. Photo: Michael Sandler

On December 4, Nathaniel Masahi Takatsuno (22) fell to his death while free soloing Leonids, a three-pitch 5.9 on The Wedge at El Cajon Mountain an hour east of San Diego.

Climber Michael Sandler witnessed the accident. In his report to Accidents, he wrote:

“As we were waiting (at the base), a single man walked by. I asked what his name was and we made some small talk. His name was Nate (Takatsuno), and he was a lab tech at University of California San Diego. He was alone but had a rope, so I asked him what route he was planning to do. He told me he wanted to solo Meteor—I asked if he was going to rope solo. He said no but was planning to carry up the rope in a pack and use it to rappel. I asked if he just didn't have any friends who wanted to climb, and he said that he did, but that he liked soloing. We observed that he was not planning to wear a helmet.

“At this point he started up the crag. He seemed gripped on even the third bolt—he was on the nearby Leonids (5.9) and not his intended route, Meteor (5.8). However, he made it up past the tricky start and kept heading up. As he did so, he would occasionally grab bolts; he had a small amount of gear with him to assist in this. He passed by another party that was already rappelling down the formation. They exchanged some words and asked if he was doing well. They reported that he was continuing to occasionally grab bolts.

“I was leading the first pitch of our route, when I felt a soft thud and gust of wind. I looked around and saw him fall to the ground.”

Sandler also said, “He (Takatsuno) was on the second pitch of either Meteor or Leonids, not sure. The two routes are very close together. He hit the trail and then continued down the steep hillside. Another party had just finished rappelling to the ground. I asked my partner Andrew to tie me off and I went direct into the closest bolt. A member of the other party said he was a Wilderness First Responder, so he went down the hillside to help. We immediately called 911 and were on the phone with the operator for the next 40 minutes.”

Helicopter from the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department lowering a paramedic to the accident scene. Photo: Michael Sandler

Sandler continued, “Helicopters arrived in approximately 45 minutes and dropped a paramedic. He took our info, looked at Nate, and then was picked up by the helicopter. We called the sheriff's office to figure out what they wanted us to do. They made it sound like it was alright for us to go, but we felt that they would be unable to find the body without very clear markers. We used climbing tape to mark the location.”

According to Climbing.com, Takatsuno’s body could not be recovered until the following day due to the late time of the accident.

Analysis

While we cannot ascertain what caused the fall, the route was in the sun, which may have been a factor. Sandler wrote, “It's south-facing and pretty inland, so it gets pretty hot (and it was definitely pretty warm that day). The easier climbing is usually techy face climbing, it never quite feels 'comfortable.’”

Rock quality may have played a factor. The Wedge was described in a 2010 Mountain Project post as having “plenty of ready-to-snap micro flakes and a few larger hollow bits.” ANAC Southern California reporter Christy Rosa, who has climbed Leonids, says, “The route he was on is 350 to 400 feet long, mostly solid granite, but a bit crumbly and flakey at a few points.” She adds, “It is one of the best routes in San Diego, so it's well traveled.”

Climbers on Meteor, the route to the right of Leonids. It is clear how close the falling free soloist was to Sandler. Photo: Josh Bedard

While there’s not much educational nor technical analysis to be made in free solo accidents, Rosa notes that this incident was the third free solo death in Southern California this year. As an ER doctor, her assessment is suitably objective, “The increased number of free solo accidents is simple math: More people are free soloing. This is likely a combination of seeing others successfully do it, and perhaps an increase in risk tolerance, as the pandemic has changed most of us.”

Sandler had several things to say. He pointed out that, “If, for whatever reason, you must free solo, do so on climbs well below your ability, ideally ones you have done before. From our discussion with Nate and his apparent discomfort on the climb, this was not an appropriate climb to be ropeless on.” Perhaps Sandler’s most important observation was to encourage soloists to think of others. “As a free soloist, you put the lives of those below you at risk. He flew by less than five feet from me; a collision could have led to serious trauma for myself.” Witnessing trauma can itself be traumatic. Sandler adds, “Thankfully, I'm doing okay. I had regular flashbacks for probably a week or so afterward, but those have thankfully become less frequent.”

Join the Club—United We Climb.

Get Accidents Sent to You Annually

Partner-level members receive the Accidents in North American Climbing book every year. Detailing the most noteworthy climbing and skiing accidents each year, climbers, rangers, rescue professionals, and editors analyze what went wrong, so you can learn from others’ mistakes.

Rescue & Medical Expense Coverage

Climbing can be a risky pursuit, but one worth the price of admission. Partner-level members receive $7,500 in rescue services and $5,000 in emergency medical expense coverage. Looking for deeper coverage? Sign up for the Leader level and receive $300k in rescue services.

Happy Warnings from the Editor

It’s the holiday season at Chulilla in eastern Spain. It’s my first time in this world-class area, and I’m fortunate to be clipping bolts on warm Spanish limestone. It’s a reminder that, while favoring athleticism over risk, sport climbing arguably holds perils for a greater number of climbers than other discipline, due to the sheer volume of participants and the repetition of critical tasks. The latter includes lowering, untying, retying, taking, and catching leader falls. Beginners and experts alike can benefit from remembering good belay practice, and even then, accidents can occur when unusual factors come into play.

A few days ago, I was belaying a partner on a difficult 40-meter pitch. He was using a brand new 8.9mm rope in order to write an online gear review. Though there were plenty of falls and takes, one hazard we avoided was unintentional slippage from a skinny and very slick rope. This can be an issue even when the belayer does (almost) everything right.

So, as I wish you safe and happy holidays, I’ll leave you with a short video that addresses this potential hazard. The video, which focuses on the Petzl Grigri but applies in similar ways to any assisted-braking belay device, is from a YouTube channel called Hard Is Easy. @HardIsEasy takes an analytic and often entertaining approach to gear, training, and technique. — Pete Takeda

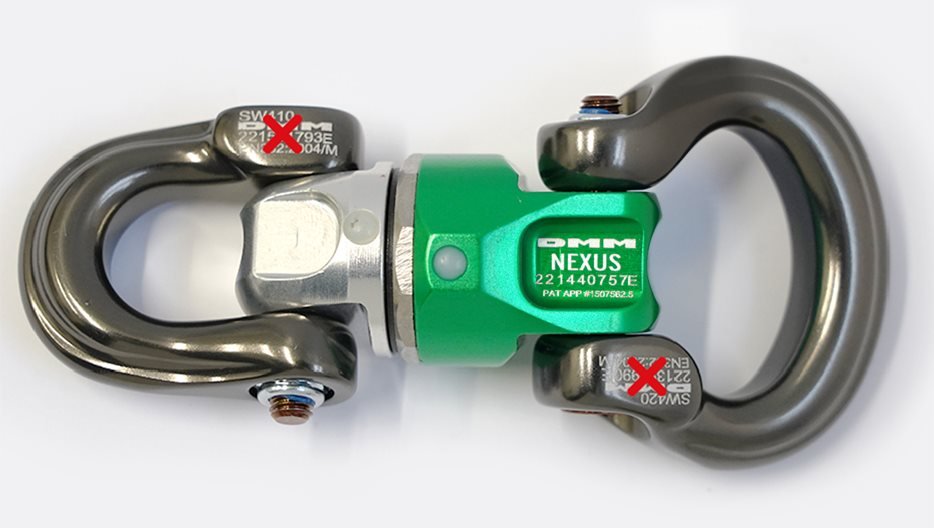

DMM Swivel Devices Recalled

Recently, DMM was made aware of a near-miss incident involving the failure of a DMM Director connector. These and similar devices are frequently used by rescuers and some possibly by big-wall climbers. Though the user was unhurt, DMM has issued a recall for nine items in their product line.

Shop the ANAC Collection

The Prescription newsletter is published monthly by the American Alpine Club.