This month we have an unfortunate accident that occurred several months ago on a popular one-pitch sport route at Sand Rock, Alabama. This accident underscores the sometimes perilous learning curve faced by those transitioning from indoor to outdoor climbing.

Andrea Bender climbing Misty (5.10b/c), the scene of a fatal fall in October 2023. Mountain Project reports that this climb is “not to be missed.” Photo: Andrea Bender Collection

Fatal Fall From Anchor | Inexperience, Inadequate Supervision

Alabama, Sand Rock, Sun Wall

On October 14, Yutung “Faye” Zhang (18) fell 90 feet from the anchors of Misty (5.10b/c) while cleaning this route at Sand Rock in northeastern Alabama. It was her second time climbing outdoors. At around 12 p.m., Zhang, a new climber and part of a larger group, took a final top-rope lap on the route. She cleaned the quickdraws and reached the two-bolt anchor. The anchor was equipped with two mussy hooks plus a single locking carabiner that had been placed by one of the other climbers to guard against the rope from unclipping from the mussys.

No one was at the anchors with Zhang to see exactly what happened. Jun C., who was belaying Zhang at the time of the accident, wrote on Mountain Project, “We put the locker in on the incredibly unlikely premise that the mussys could come unclipped. Not that any of us really thought that would happen, but we wanted to keep our party safe. [While Zhang was on the ground], we communicated and demonstrated what she was to do when she got to the top.... She was aware and confident of just needing to remove a locker and leave the mussys clipped.”

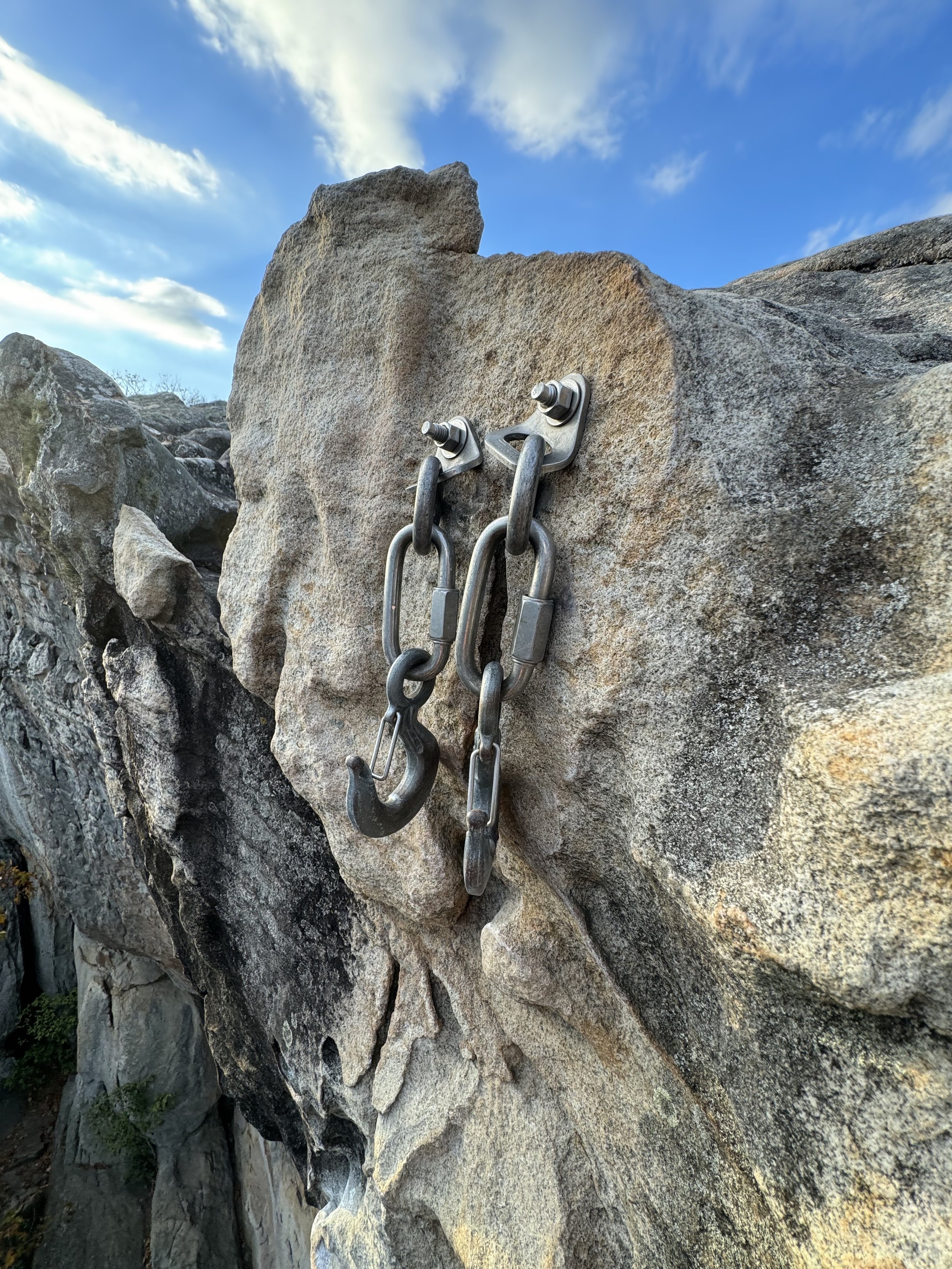

The anchor at the top of Misty. Karsten Delap, a guide who visited the area after the accident, said, “When she undid the (locking) carabiner, she was probably a little bit above [the mussys], with a little bit of slack.” Photo by Karsten Delap

It is assumed that after removing the locking carabiner at the belay, Zhang somehow unclipped the rope from the mussy hooks. Jun C., the belayer, wrote, “Suddenly the rope became unweighted and she (Zhang) wasn’t clipped through the mussys anymore. I fell and smacked my back and head against another rock, and she fell right beside me…. A few of us trained in emergency first response came to aid immediately, as well as a physician that just happened to be in the area. EMS response was quite fast as well, but there was really nothing to be done.”

Jun C. added, “Between all of us we have decades of climbing experience. In our eyes, this [lowering from the mussys] was routine and one of the safest things we could ask of a relatively new climber.” The belayer added, “At the same time, I know all of us are kicking ourselves for asking her to do anything at all.… We’ve all been thinking about what we could or should have done differently or how this could have been a safer experience.” (Sources: mountainproject.com, climbing.com, and the Editors.)

ANALYSIS

A few weeks after the accident, IFMGA guide Karsten Delap climbed this route and provided ANAC with some images and video. He observed that the best handholds at the end of Misty were located above the bolts. (See the video below.) This may have positioned Zhang above the mussys. Then, as Zhang weighted the rope, it might have loaded the mussys incorrectly and become unclipped.

A more in-depth article on best practices for using mussy hooks, written by Delap, will appear in the 2024 ANAC. For now, he writes that, “It is plausible that the rope was threaded from right to left on the mussy hooks, with the locking carabiner positioned between the two hooks. As the climber approached the anchor from the right side, an attempt to remove the locking carabiner involved pulling up above the mussy hooks to introduce slight slack into the system. While this facilitated the removal of the carabiner, it also inadvertently positioned the rope over the gates of the mussy hooks. The belayer, responding to the climber's movement, probably took up slack, felt the climber's weight, and subsequently the gates of the mussy hooks back-clipped under the full force of the climber's weight. This resulted in the rope becoming dislodged from the anchor.”

BE A PRO, KEEP IT LOW

Delap noted that the addition of a locking carabiner to a mussy hook belay was inappropriate for the system. In this case, the locker probably brought the rope above the plane of the hooks, a mistake when considering the “open” nature of mussy hooks.

After the accident, Delap posted an Instagram video detailing some best practices for mussy use. Click here or on the photo to see the video.

“The best thing you can do is always stay below the mussy hooks, both with your anchor setup and your body,” Delap writes. “So be a pro, keep it low.”

Greg Barnes is executive director of the American Safe Climbing Association (ASCA). Though Barnes is a proponent of lower-offs such as mussy hooks, he says these useful tools have inherent limits.

He wrote to ANAC: “Lower-offs include hooks, ram's horns, fixed carabiners, etc. We have had a policy of avoiding hooks for popular top-rope-accessible routes because of the chance of hooks becoming unclipped as someone transitions to rappel.”

Although mussys have a proven safety record, Barnes believes, they still require eduation. He writes, “In Owens River Gorge, lower-offs [have been] the standard since the early ’90s. Despite very heavy climber traffic for 30 years, there have been very few anchor changeover accidents compared to similar areas with closed anchors. In the Sand Rock case, we don’t know whether the rope became accidentally unclipped or if the climber unclipped them on purpose. It is wise to have direct supervision—namely an experienced climber at the same anchor—when a new climber cleans an anchor.” (Sources: Karsten Delap, Greg Barnes, and the Editors.)

Sign Up for AAC Emails