Eleanor Davis (sitting) and Eleanor Bartlett atop Sentinel Peak (part of Pikes Peak). Photo courtesy of the Bartlett Collection, AAC Library.

The First Female Ascent of the Grand Teton, and What It Means to Discover a Ghost in the Archives

By Hannah Provost

More than teaching me something revolutionary about climbing history, the archives that hide Eleanor Davis taught me about myself.

Without knowing it, I went into this project wanting a particular story to unfold. I wanted Eleanor Davis, an objectively important woman to climbing history, to reveal her secrets, and for those secrets to justify the philosophical importance of climbing. I wanted to hear an echo of myself from a century ago—to confirm that there is some deeply meaningful reason to climb—and to hear it from a woman, a legacy I could make meaningful and specific to me. But not all climbing conversations are revolutionary. Similar to the mundane spray of beta and grade debate that we often come across today, Eleanor Davis recollections focused on memorable moments of snarkiness, on minor crises, on the character of her climbing partners—not a revolutionary narrative of what climbing means.

Instead, they are simply memories of a personal relationship to climbing and the mountains.

Eleanor Davis is largely a ghost in the archives. But we do know a few key things. August 27th, 2023, was the centennial of her ascent of the Grand Teton, the first female ascent of this iconic mountain. Davis was also the second half of the ascent team for the FA of the 50 Classic Climb Ellingwood Ledges—though you wouldn’t know it by the name. Other than these two proud ascents, and seemingly only one photo of her atop a summit sitting beside Albert Ellingwood, her story is largely unwritten and undocumented. As the centennial approached, and I heard about upcoming celebrations of this historic moment, I wanted to contribute to changing that. I wanted to uncover her story—and have it transform our understanding of female mountaineering, of course.

From left to right: Albert Ellingwood, Barton Hoag, and Eleanor Davis on the summit of Pyramid Peak,1919, Courtesy of Hoag Family, Bueler Collection, AAC Library.

Through the American Alpine Club’s Library, I got access to two interviews with Eleanor Davis that rarely see the light of day. Researcher Jan Robertson had conducted a series of interviews with important female mountaineers for her book project, The Magnificent Mountain Women. When Robertson interviewed Eleanor, she was 99, and would live for 8 more years. I combined this interview with an oral history with Eleanor Davis, taken in 1983 for History Colorado. Though the audio for the interview was incomprehensible, the notes taken of the interview were very illuminating.

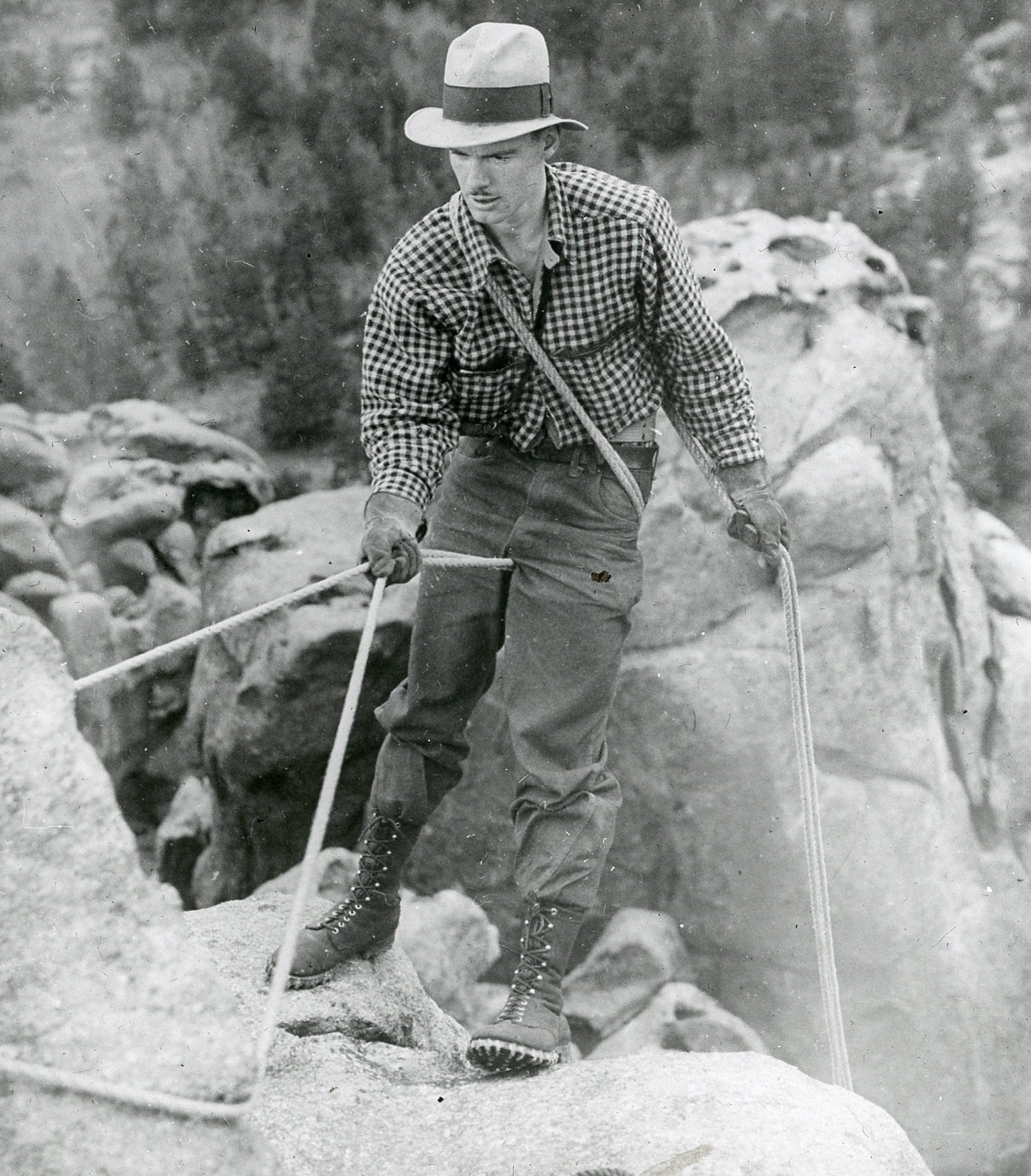

The Dulfersitz method of rappelling. Photo Courtesy of the CMC Collection.

Weaving in and out of threads of conversation, the audio of the interview from 1985 is cluttered with historic nuggets. Davis was one of Albert Ellingwood’s main climbing partners for years, and her casual references to him belie the massive impact his climbing would have. Ellingwood is credited for being the first person to substantially utilize rope systems and other “proper rock climbing technique” in Colorado, and many times, Davis was in the rope party or repeated the difficult new routes that Ellingwood was putting up. Davis meandered through details of biking to the mountains when there was gas-rations during the Depression, and recounted that when Ellingwood first taught them how to rappel with the Dulfersitz method, that “we thought it was fun but sort of silly too,” what with how slow you had to go to avoid rope burns. I reveled in the details that put our modern world into perspective: apparently Davis didn’t enjoy climbing in a skirt, like most women of the day, and instead had her dressmaker turn her climbing skirt into knickerbockers, or baggy pants gathered at the knee. She didn’t use a sleeping bag but instead surplus army blankets and a tarp. She mentioned jello as a key food for such outings—I think we should bring this trend back. But it wasn’t all grit and toughness—Eleanor and Albert hated alpine starts and often got back in the dark, or slept on a rock ledge when they got benighted.

Davis swore she never took a fall when climbing, and that the only climbing accident she ever witnessed was rockfall hitting her friend Jo Deutschbein in the head when a party climbing above dislodged some choss. Yet she was less interested in analyzing accidents that really did happen, and instead was more intrigued by the drama of a potentially tall tale. Her friend Eleanor Bartlett always insisted that Albert Ellingwood and Bee Rogers were struck by lightning when the group was climbing Blanca Peak, resulting in a fall—though the effects of the strike must have been temporary, because Davis, being the last member of the party, never was sure if Bartlett’s tale was true.

Eleanor Davis climbed with Agnes Vaille and Betsy Cowles, two mountaineers who are hidden in the archives nearly as much as Davis. But rather than list their accomplishments together, what Davis remembered were their personalities—they were intellectual, wise, and Betsy threw great parties. Before Cowles got married, Davis remembers her saying “Oh Eleanor, I’m marrying a wonderful man. And he likes the mountains too, and that’s just frosting on the cake.”

Despite her extensive experience, and her preference for Ellingwood as a partner, Davis occasionally had to fight to be taken seriously as a mountaineer. On a trip to the Arapaho Peaks, she was told that only a “very select group could go on the North Peak.” She responded, “Well I’m very select.” Her confidence must have won her some points, or perhaps our gear really does tell much about our experience or gumbiness—they looked at her shoes and her camping equipment, and determined that perhaps she was right. She summited Arapaho without a hitch.

Photo Credit: Ben Farrar

Even when it came to reflecting on her ascent of the Grand Teton, in 1923, all she had for me was a minor crisis. She and Ellingwood had climbed out on a ridge on their stomachs, and Ellingwood needed a leg up. So Davis leaned over to give him a shoulder to stand up on, knocking her glasses off in the process, sending them skittering down clear to the glacier below. Thankfully, Davis mainly needed the glasses for reading, and could get along fine without them, as evidently they made the summit—and made history.

When I first listened to these scattered stories, I was a little disappointed. But as I sifted through her stories, and read and listened to them again and again, I started to recognize a certain gleam to them. Eleanor Davis was a woman who did extraordinary things for her time, and yet she valued the ordinary—the humble minutia of what makes climbing so rich as a life experience.

I am not a climber who does extraordinary things for my time. Most of us aren’t. Most of us think our climbing partners are funny, and have to stand up for ourselves occasionally to get taken seriously, and have minor-crises, not epics—just like Davis. Yet often, I am dissatisfied with that.

Getting to know Eleanor Davis, from the few archives I could find, made me really like her—her spunk, her genuine glee when she mentioned the mountains, her care for her climbing partners. Getting to know Eleanor Davis also made me learn a lesson I’ve been needing to learn again and again from climbing: What gets us to the top of the pitch, or the mountain, is incomparable to someone else’s reasons. Perhaps that's why Davis was so humble about her accomplishments. She herself didn’t need anything grand to come from the Grand—because it was already there, in the minutia.