by Eric Rueth

K2. Jack Durrance Collection.

After the successful reconnaissance of K2 in 1938, the Second American Karakoram Expedition was poised to make history. A route on the Abruzzi Ridge had been established up to 26,000 ft. with locations for campsites and beta on the difficult sections of climbing. If weather permitted, there seemed to be no good reason why history would not remember the Second American Karakoram Expedition as the first to summit K2 and the first to conquer an 8,000m peak. But the events would play out differently on the mountain and history now remembers the 1939 expedition for its tragedy and the controversy that followed.

The party that arrived at the base of K2 in 1939 was not a strong one. It was originally planned to include 10 members but after dropouts for various reasons it dwindled to five. The biggest issue with the loss of these members was that they were the five most qualified members (excluding Wiessner) and left the expedition with no returning members of the 1938 expedition. A last minute addition brought the party up to six and included: Fritz Wiessner, Eaton Cromwell, George Sheldon, Chappel Cranmer, Dudley Wolfe, Jack Durrance (the last minute addition). They were also accompanied by a British Transport Officer, Lt. George Trench and 8 Sherpa who climbed up the mountain: Lama, Kikuli, Dawa, Tendrup, Kitar, Tsering, Phinsoo, and Sonam.

1939 Expedition members. Left to right, standing: George Sheldon, Chappell Cranmer, Jack Durrance, George Trench; seated: Eaton Cromwell, Fritz Wiessner, Dudley Wolfe. Jack Durrance Collection

The weakness of the team was not that any of the members were on the team; it was that these members were the team. Each team member had their strengths but unfortunately also their limitations. As climbers kept dropping out of the expedition, it lost its well-rounded and experienced members that could have potentially brought the best out of the team. Fritz Wiessner was the only fully qualified and experienced climber to arrive at K2. To add to the weakness of the team, a number of events weakened it further.

First was that due to the timing of Durrance’s addition, his boots were set to arrive at some point after the party’s arrival at K2. The boots finally arrived four weeks after the party was making their way up the mountain. Durrance proved to be one of the harder working team members but was hindered by his footwear. Without his high altitude boots he was limited to staying below 20,000 ft. Even with staying at the lower camps Durrance’s feet were taking a beating and hindering his productivity.

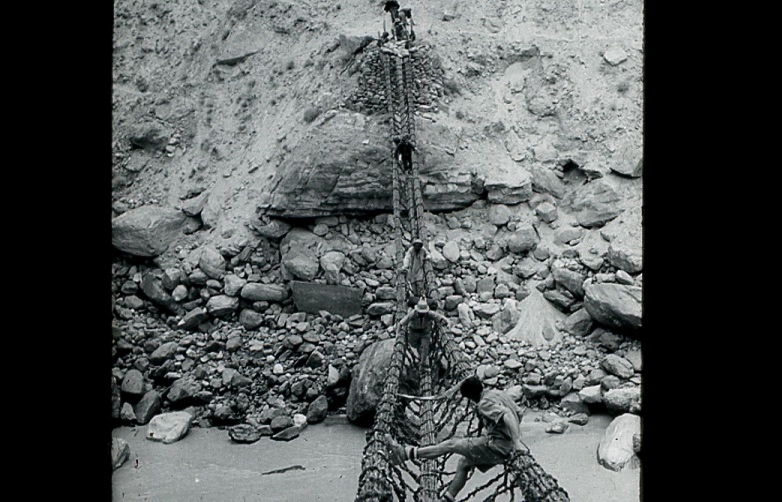

The second event was one that had the expedition not ended in disaster probably would have gone unnoticed. When Wiessner and Wolfe were gathering the supplies for the expedition they did not purchase enough snow goggles for the porters. Expedition members created makeshift glasses by cutting narrow slits into pieces of cardboard. Shortly after beginning the days march toward K2 three porters suffered from snow blindness. The three were sent back to Askole and their loads were divided between Cranmer, Durrance, Sheldon, and Trench. The extra weight effectively created a double-carry for the four.

The third event would weaken the expedition’s manpower by one sixth. On May 30th, Cranmer spent some time in a crevasse trying to retrieve a tarpaulin that was dropped by one of the porters. Cranmer emerged with the tarpaulin but also severely chilled and exhausted. Cranmer then carried the extra weight from the loss of porters to snow blindness on May 31st adding even more exhaustion. Cranmer rose from his tent on June 1st to announce that he did not feel well before he retreated back inside. Hours later, Cranmer would be coughing up more than three coffee cups worth of a, “clear, frothy fluid” and was slipping in and out of states of delirium and consciousness. Years later Durrance stated, “I never knew anyone could be so sick and stay alive.”

Now at the mountain and before committing to the difficult climbing on the Abruzzi Ridge, Fritz and Cromwell took a day to get a view of northeast ridge. But as it was in 1938, no viable route presented itself. So, the Abruzzi Ridge was the route to the summit. Loads were carried and routes established following the footsteps of the year before. To avoid the dangers of rock fall Camp III (20,700 ft.) was used only as a supply cache.

As the route progressed upward, almost exclusively led by Wiessner, morale began to decline. Storms battered the expedition and battered ambition. A chasm was beginning to open in the expedition, one of motivation and physical distance. Wiessner and Wolfe never wavered in their ambition or optimism of reaching the summit, while the rest of the members seemed to grow lethargic and hesitant to continue pushing up the mountain. Wiessner and Wolfe continued up while the majority of the expedition tended to stay in the lower camps with Durrance typically somewhere in between.

The battering storms that weakened morale also made a physical impact on the team. The cold of the storms nipped Sheldon’s toes. Sheldon continued working on the mountain until the weather improved. With the arrival of warmer weather his feet began to swell and he could do little more than hobble, which he did down to basecamp. Physically, two of the six of the expedition members were incapacitated.

The 1939 expedition would establish two camps higher than the previous year. Camp VIII was established at 25,300 ft. and Camp IX at 26,050 ft. Both were stocked well enough to support a push to the summit. July 18th saw an attempt for the summit from Camp IX by Wiessner and Lama. Meanwhile, Wolfe was well supplied but alone at Camp VIII. Durrance, the closest American to Wolfe was at Camp II (19,300 ft.).

It was a harrowing attack that brought the pair to 27,500 ft. just 700 ft. from the summit. Wiessner wanted to continue upwards but Lama did not. The time was 6:30 p.m. and proceeding upward would mean descending at night. Wiessner saw the route that lay ahead and was confident they would be able to reach the summit on the second attempt.

On the retreat to Camp IX, Lama’s crampons that were strapped to his pack became tangled in rope and ended up being lost. On the second attempt the loss of crampons came into play. In order to ascend without crampons step cutting became necessary and it was apparent that the task would take too long. So the team descended again, this time to Camp VIII, to restock.

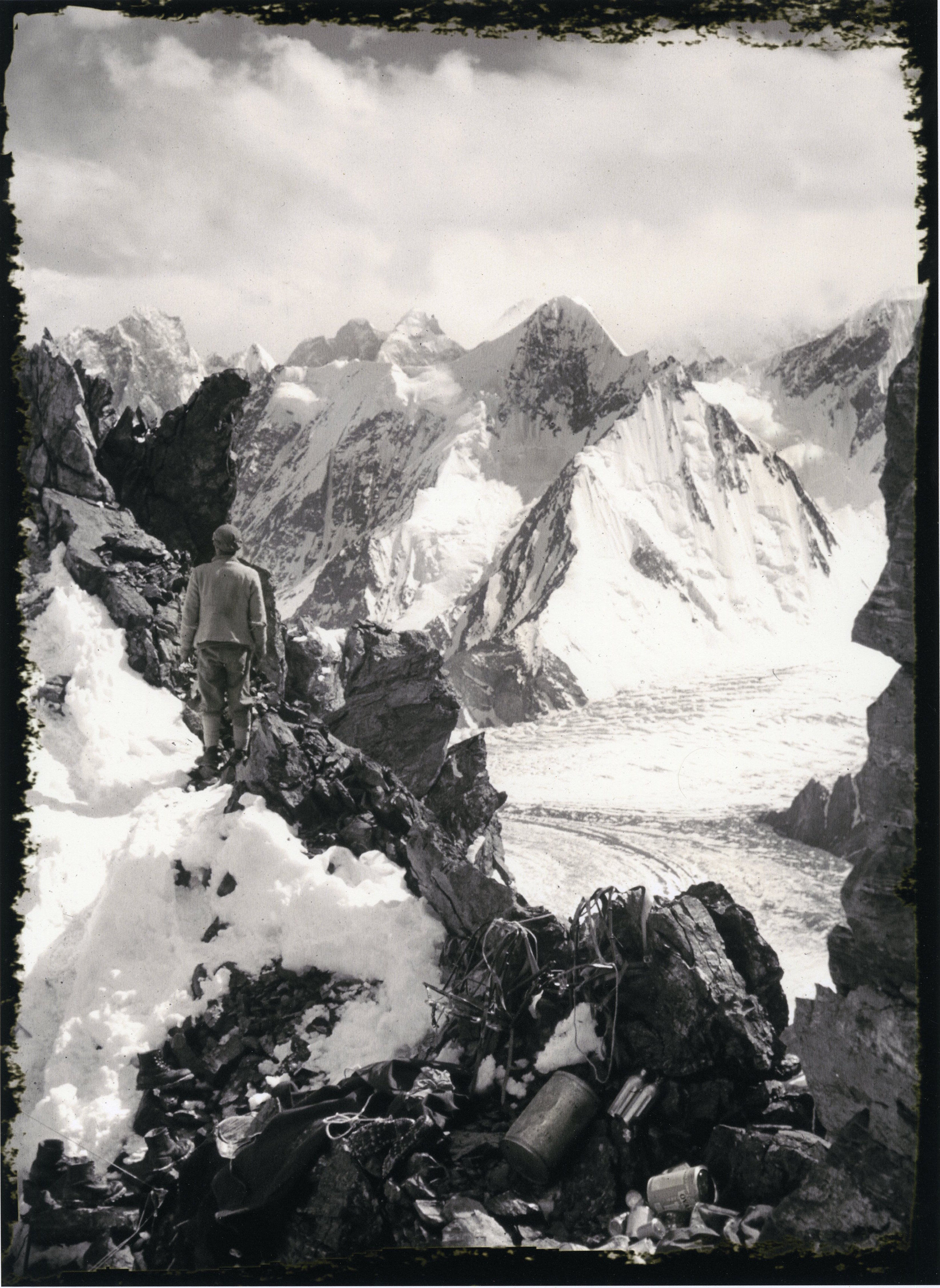

Jack Durrance Collection

Wolfe informed the pair upon their arrival that no loads from below came up during their absence. This left the provisions at Camp VIII too little to support another summit attempt and another descent was made. Now a trio, Wiessner, Lama and Wolfe made their way to Camp VII. What was found at Camp VII was devastating and exacerbated by a fall that Wolfe had taken en route where he lost his sleeping bag. The majority of the supplies at the camp had been stripped leaving the trio with one air mattress and one sleeping bag.

With much frustration and confusion about their current situation, Wolfe would remain at Camp VII while Wiessner and Lama would continue downward to Camp VI. A deserted Camp VI saw the duo continue downward only to find empty camps littering the route. After an awful night’s sleep wrapped in a tent at Camp II, Wiessner and Lama made their way into basecamp exhausted and suffering from the cold. There would be no more attempts for the summit.

Wolfe still lay alone 24,000 ft. and Durrance, Dawa, Phinsoo and Kitar started up to retrieve him. On July 25th they ascended to Camp IV. Durrance and Dawa were ill the next day so Phinsoo and Kitar continued on the Camp VI. Camp VI also saw the arrival of Kikuli and Tsering who in a single day ascended from basecamp, 6,900 ft. below! The first contact with Wolfe on July 29th found him in dismal condition. He convinced his rescuers to come back for him on the morrow when he would be ready.

Poor weather delayed their second attempt until July 31st. With the weather still poor Kikuli, Kitar and Phinsoo went to retrieve Wolfe. On August 2nd Tsering returned to basecamp alone. He relayed the previous days’ activities and that he hadn’t seen or heard from the neither three Sherpa nor Wolfe since the second attempt to retrieve Wolfe departed Camp VI.

One more attempt was made to reach the high camps to see if there was any sign of life high up on the mountain, but Camp II would be the highest they could reach. On August 9th Kikuli, Kitar, Phinsoo and Wolfe were presumed dead and the expedition departed from K2.

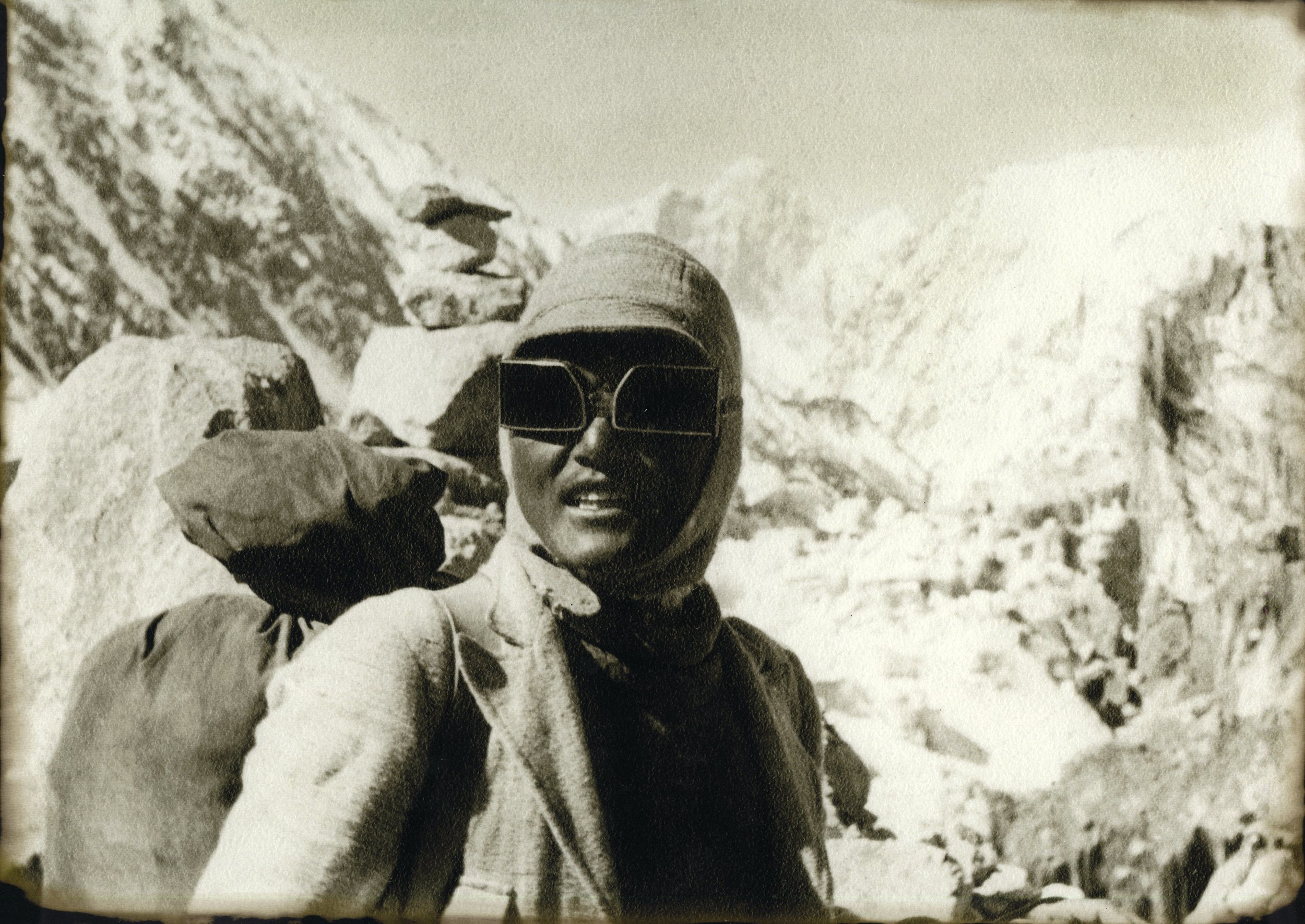

Pasang Kikuli. Jack Durrance Collection

Read about the 1938 Reconnaissance of K2 here.

Read about the 1953 Third American Karakoram Expedition here.

*Photos from the Jack Durrance Collection restored by The Photo Mirage Inc.

By Eric Rueth