by Allison Albright

“Buying an [ice] axe should be the beginning of a long partnership.”

The modern ice axe is the end product of a long history of tools being adapted, redesigned and specialized. Its first incarnation was actually as two different tools: the hand axe and the alpenstock. Over the years, these two implements were melded to create the ice axe of the late 19th and early to mid 20th centuries. While ice axes of that type are still in use and production today, offshoots of that tool have evolved back into two separate pieces of equipment again: the ice tool and the trekking pole.

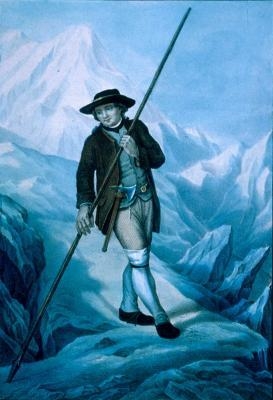

The Alpenstock

The oldest ancestor of the ice axe is the alpenstock - an implement originally used by shepherds and hunters in the Alps and the Caucasus as a tool to keep its bearer stable when walking on ice and snow. Invented sometime in the middle ages, the alpenstock was created to do the work of crampons. The earliest alpenstocks were long wooden poles of about six to ten feet in length, tipped on one end with an iron spike. They were used by planting the iron spike firmly in the ice and using the wooden staff to help pull oneself forward and stay upright on slippery ground.

Beginning with some of the earliest ascents of the Alps by mountaineers, the alpenstock was often used in conjunction with a small hatchet. The alpenstock kept one upright and the axe was used to cut steps in steep icy slopes. As the sport of mountaineering gained popularity, and the new business of mountain guiding grew, it was most common for only the guide to carry an axe, since they would be cutting the steps. The rest of the party needed only alpenstocks.

The first Ice Axes

“The methods employed differ according to the consistence of the snow or ice, but, speaking generally, the “blade” of the axe-head should be used for snow, and the “pick” for ice.”

In the 1800's these two tools were merged by affixing a pick (the sharp part) and adze (the flat piece) on one end of a wooden shaft and a spike on the other. In these early versions, the pick and adze are about the same length. Later, the shaft itself was shortened to a little under five feet on average, making it possible to both stabilize oneself on icy ground and cut steps for one's climbing party with the same instrument. They could also be used for stabilization by anchoring the cutting edge in the snow while the climber held on to the shaft, or to arrest a fall.

Made of oak, hickory or ash and including parts made of iron or steel, the alpenstocks of the late 1800's were heavy and cumbersome.

The Early 20th Century

When crampons started to be of higher quality and more reliable, the length of the alpenstock was shortened further, reducing the weight to about three lbs and creating a tool that was starting to resemble the modern ice axe. The pick side of the head lengthened until it was longer than the adze.

“I think the limit has now been reached, in the best modern axes, to this process of shaft-shortening. Indeed, in my opinion, the extra short pattern of axe, evolved by a well-known amateur, has only succeeded in becoming quite useless as an alpenstock while of very small service as a hatchet. ”

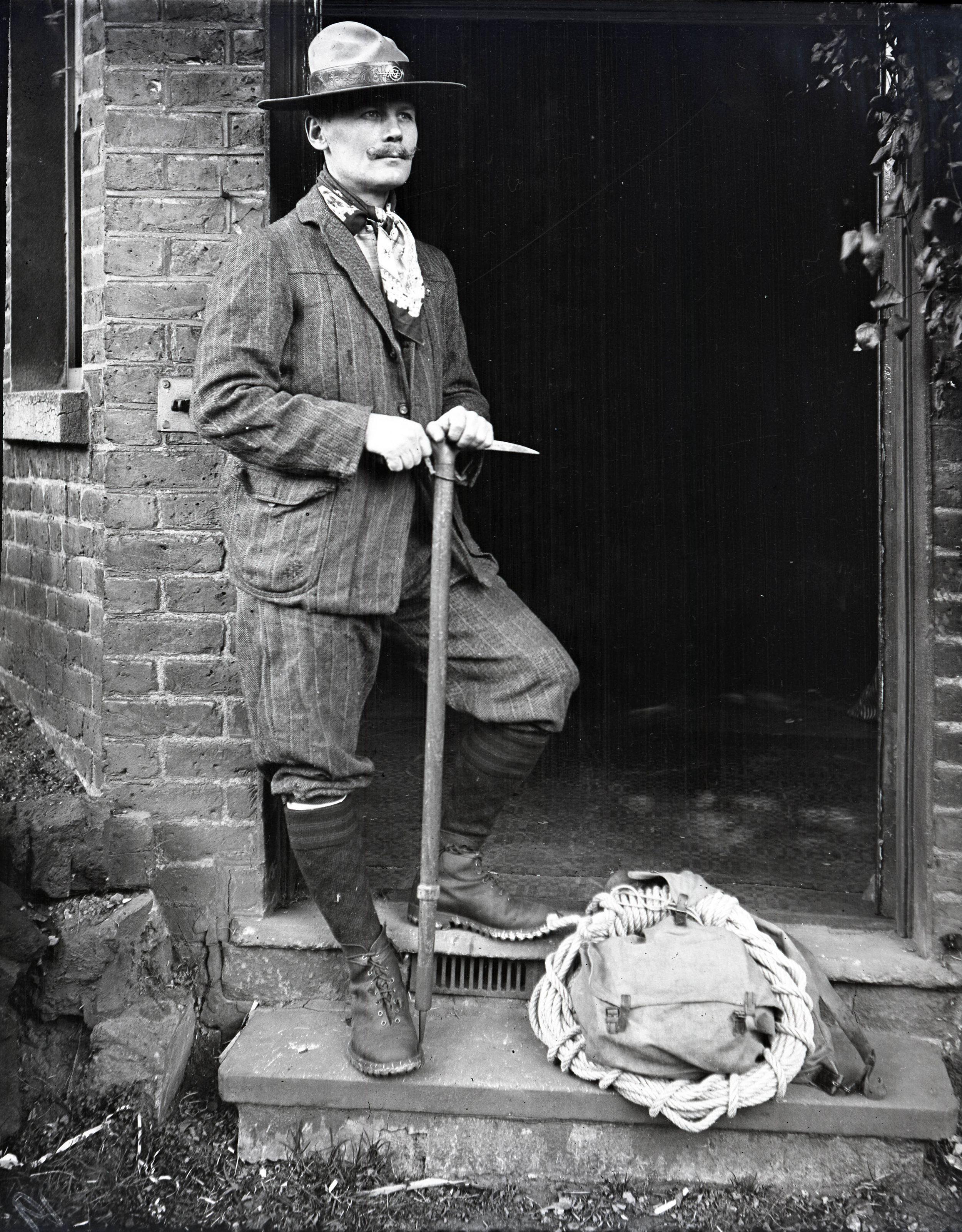

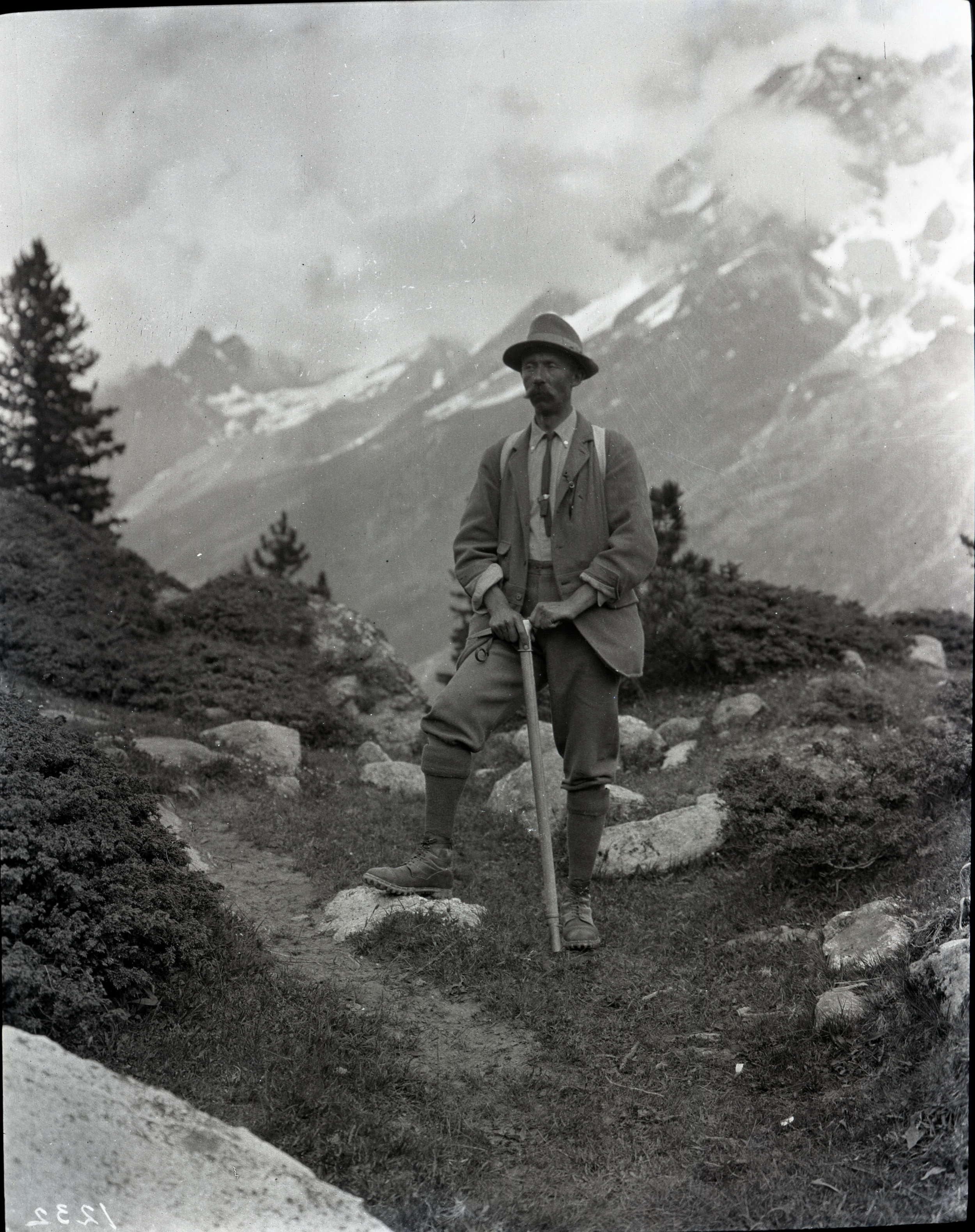

These ice axes retained much of their resemblance to their longer cousins, they usually came to about waist height, or a bit shorter. These could be used in much the same manner as the longer versions of the late 1800's, and also the same as a cane or walking stick; to provide stability while on uncertain terrain or while wearing crampons.

Fanny Bullock Workman's (1859-1925) ice axe - Workman was a prominent female mountaineer and a founding member of the American Alpine Club.

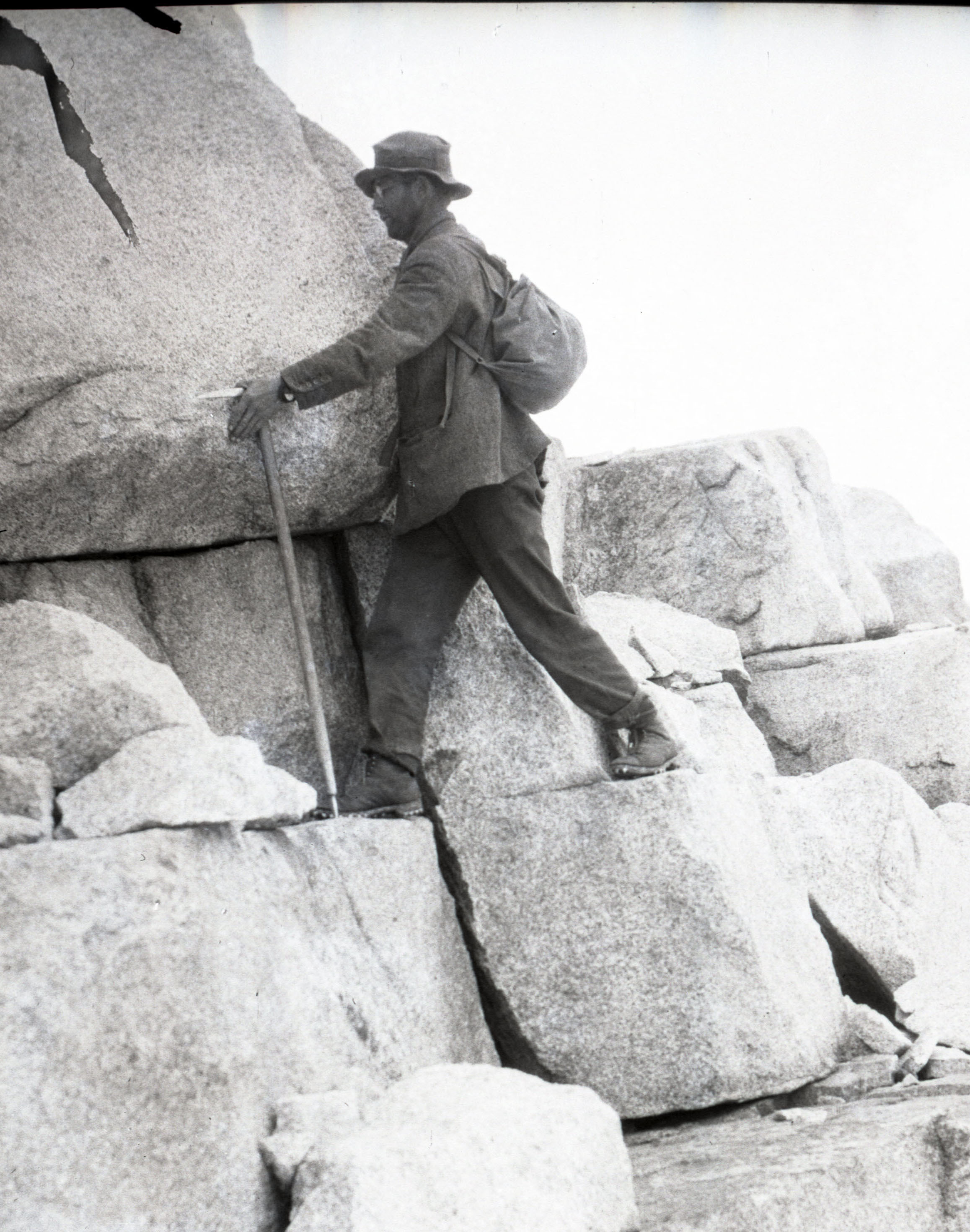

A climber anchoring himself with his ice axe

This photo is from our lantern slide collection

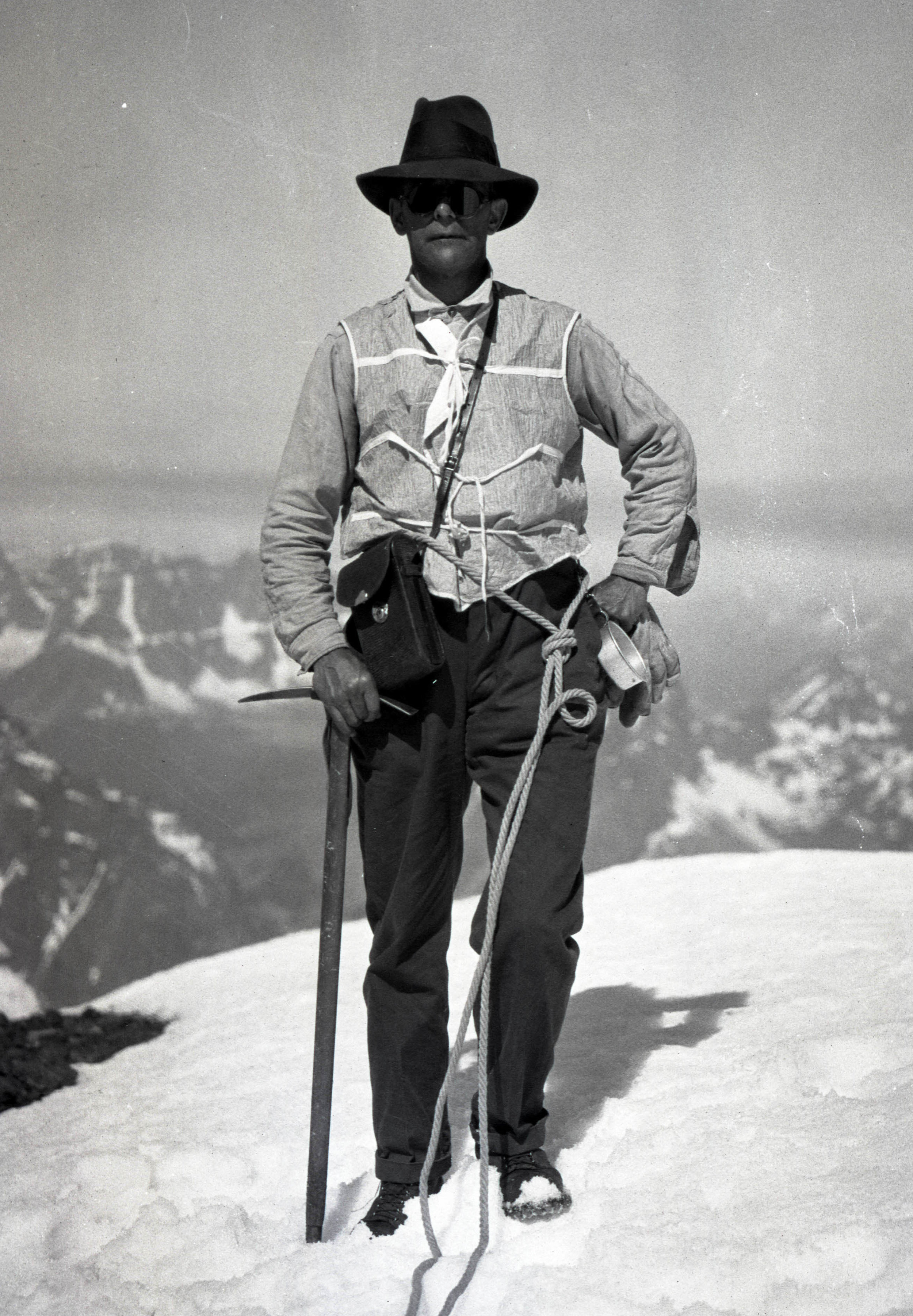

Also useful for keeping the occasional porcupine at bay

From the Andrew James Gilmour collection

Mid-20th Century

The Stubai ice axe

A popular example of the mid-century modern ice axe

Ice axes (as they were almost universally being called by that time), became shorter still. Most were about two feet in length and made of a strong wood. The pick had become very long and the adze continued to shrink.

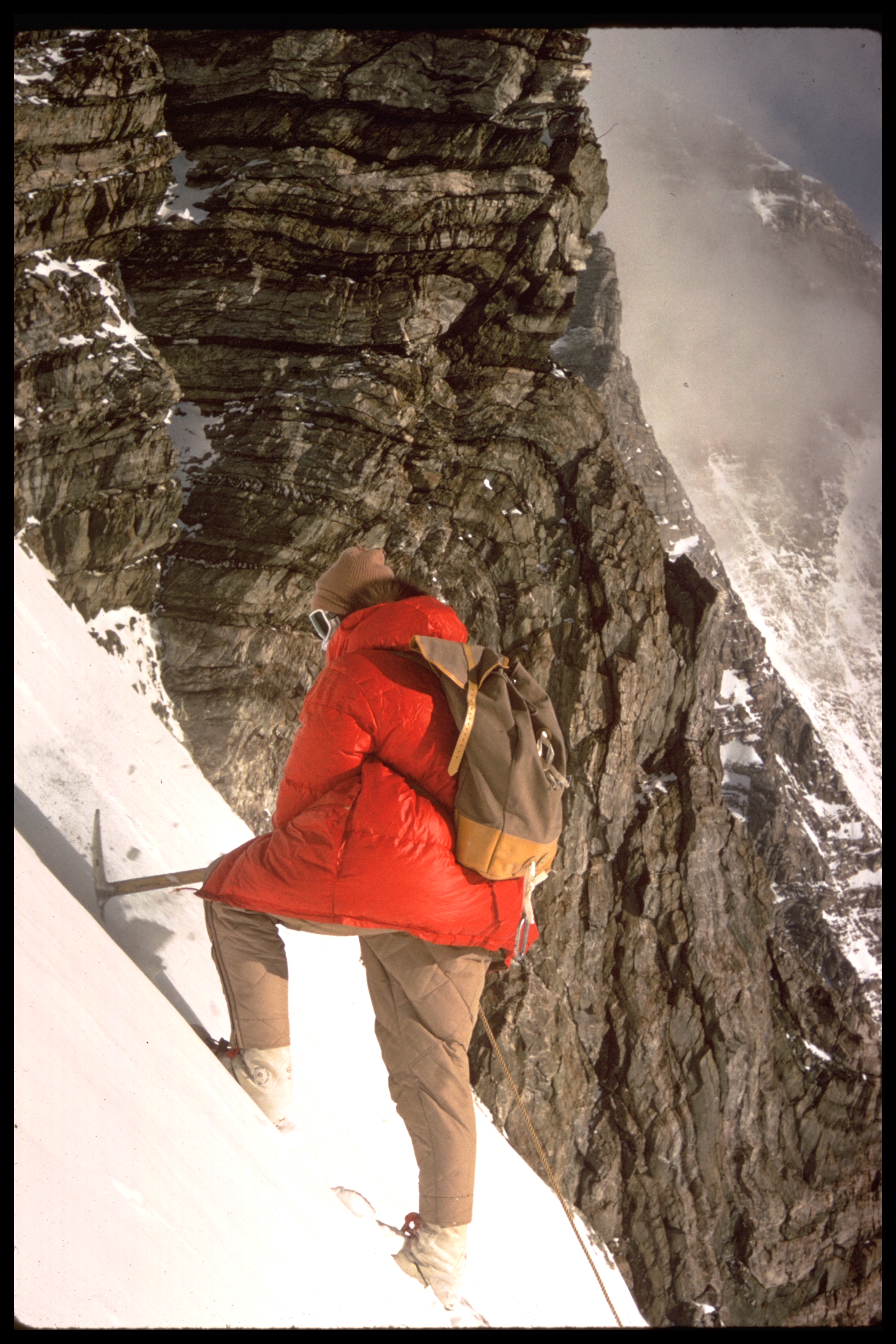

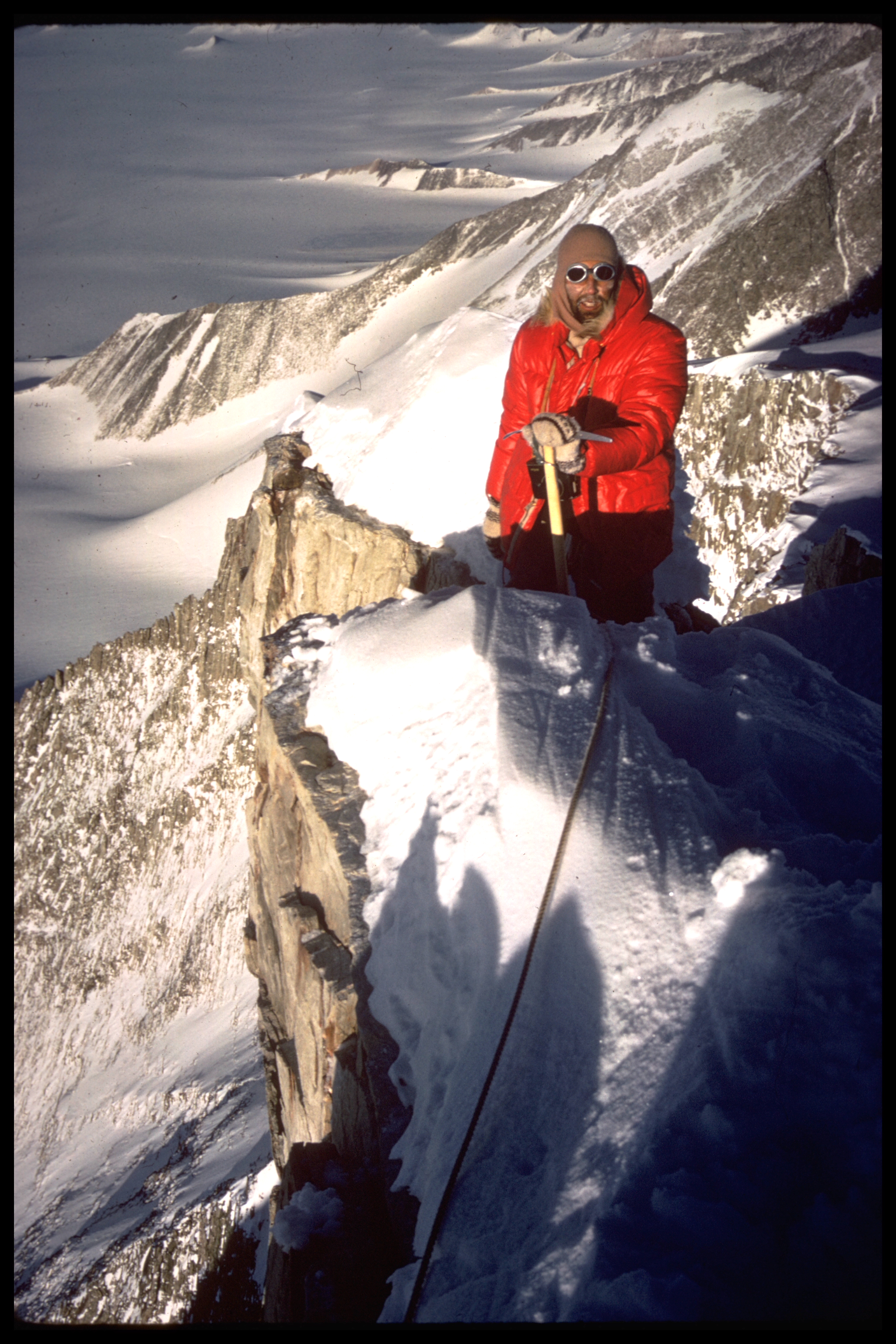

Below are some great examples of mid-20th century ice axes in use on the 1966 American Antarctic Expedition. These photos are from our Nick Clinch collection.

“Shafts may be of wood - ash or hickory - or of metal - hiduminium, as in the latest all-metal axes designed by Hamish MacInnes the Scottish mountaineer. These latter are gaining in popularity as they are less prone to breakage even when badly used and abused by novices.”

All-metal ice axes with hammers instead of adzes

As mountaineers and climbers pushed themselves and the sport into ever more challenging frontiers, they needed an ice axe made of materials stronger than wood. In the early 1960's Hamish MacInnes and Benjamin and Steven Massey started production of the first ice axes made entirely of metal called the MacInnes Massey ice axe. These ice axes were infinitely more durable than the wooden axes that came before, and were less prone to snap under pressure or if stored at incorrect temperature or humidity.

According to the Scottish Mountain Heritage Collection, MacInnes created the all-metal ice axe after being involved in the recovery of the bodies of a climbing group who fell to their deaths when the wooden shafts of their ice axes snapped.

This photo of some lovely examples of MacInnes Terrordactylice axes is courtesy of the Scottish Mountain Heritage Collection

The advent of the more sharply angled pick, as opposed to the an axe head which was entirely perpendicular to the shaft, came about in the early 70s. Early manufacturers include MacInnes-Peck with the Terrordactyl axe and Yvon Chouinard. These axes had shorter shafts which made them very useful for steep slopes. The curved blades made ascents of increasingly vertical ice possible and it wasn't long before climbers were pulling themselves up frozen waterfalls.

“A new head design of the axe uses pressing techniques, which allow a light metal steel (as used on spacecraft) to be used. The pick is dropped at an angle of 78 degrees which has been found to be the optimum angle for cutting and holding and the adze is made from the same material giving a uniform thickness throughout.

The Terrordactyl - The general impression of the hammer and adze terrordactyl is that it is the greatest aid to ice climbing since the crampon. With the deep section blade of only 1/16 in approx. thick they can be driven into the ice or snow in a down-pulling motion and in firm snow, white ice, frozen turf, etc. their holding power is amazing. [...] These new tools should allow a new standard of ice climbing to emerge.”

Through the 1980's ice axes became more specialized and diverse. The term 'ice tool' came to refer to axes more specialized to steep ice climbing, with curved and reverse curve picks, adze end variations such as hammers, and modular functionality. These tools are typically what we mean today when we speak of the ice axe. As is evident from the design, these implements have lost nearly all functionality for traction or stabilization when walking on difficult terrain. They are specialized for ice climbing.

A modern ice tool for climbing frozen water.

“There are many different types of ice axes and hammers for different kinds of winter terrain. There are tools that allow climbers to ascend vertical ice pitches, or ice walls, hundreds of feet high, varying in steepness from 85 to 95 degrees. There are tools much better suited for general mountaineering terrain where pitches are no steeper than 60 degrees.”

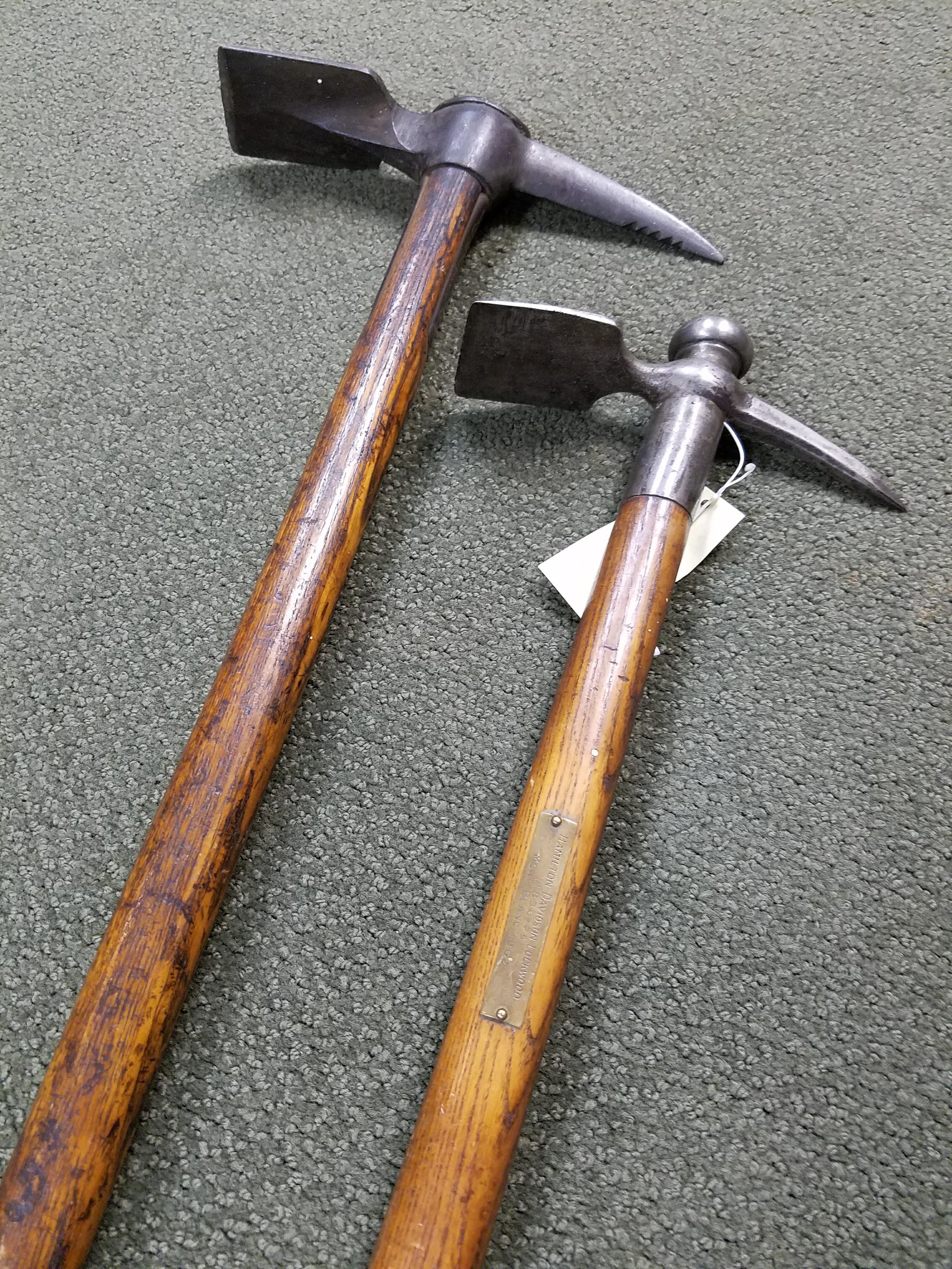

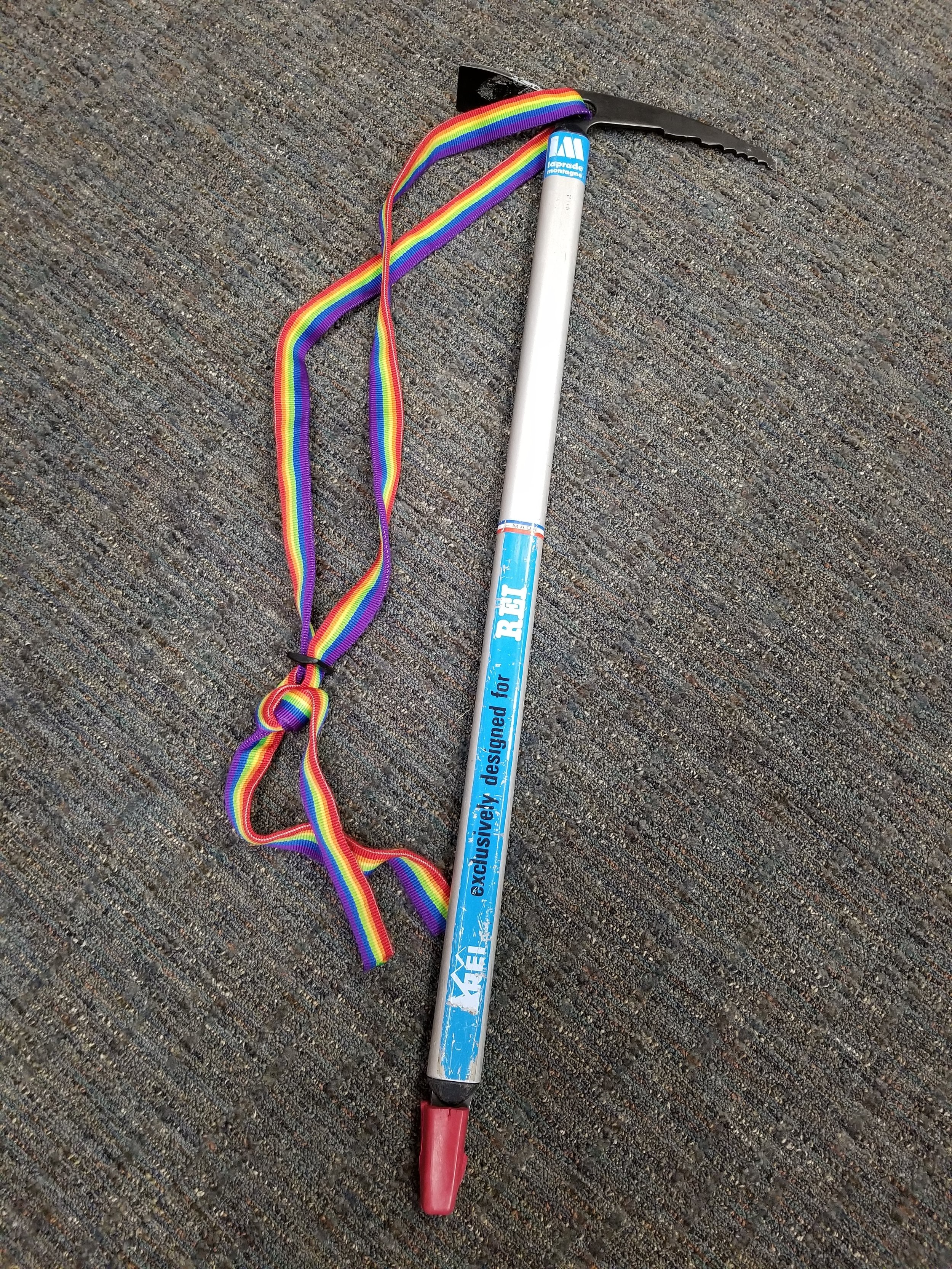

ice axes and alpenstock from our archives

Just a sample of our extensive ice axe and alpenstock collection

If you're interested in learning more, many of the resources we used here are available in the library:

Schneider, Steven. High Technology. Contemporary Books, 1980. Get it here!

Lovelock, James. Climbing. Batsford, 1971. Get it here!

Raeburn, Harold. Mountaineering Art. T. Fisher Unwin, 1920. Get it here!

Wilson, Claude. Mountaineering. George Bell & Sons, 1893. Get it here!

Some other relevant titles about mountaineering and climbing in the 20th century:

Ice Climbing by Angie Peterson Kaelberer, 2006

Ice World by Jeff Lowe, 1996

The Art of Ice Climbing by Jérôme Blanc-Gras, 2012

Ouray Ice Festival 2004 DVD

Waterfall Ice: Jeff Lowe's Climbing Techniques 2005 DVD

Call Out by Hamish MacInnes, 1977

Scottish Winter Climbs by Hamish MacInnes, 1982

Modern Mountaineering by George Dixon Abraham, 1945

Mountaineering Handbook by the Association of British Members of the Swiss Alpine Club, 1950

Special thanks to the Scottish Mountain Heritage Collection for their help with this article - make sure to check out their amazing collections online at http://www.smhc.co.uk/