by Allison Albright

A set of pitons from the mid-20th century, including LEM, Charlet-Moser, Stubai and Chouinard

Pitons are one of the oldest types of rock protection and were invented by the Victorians in the late 19th century. Pitons are metal spikes which are inserted into cracks in the rock and secured by hammering them into place with a piton hammer.

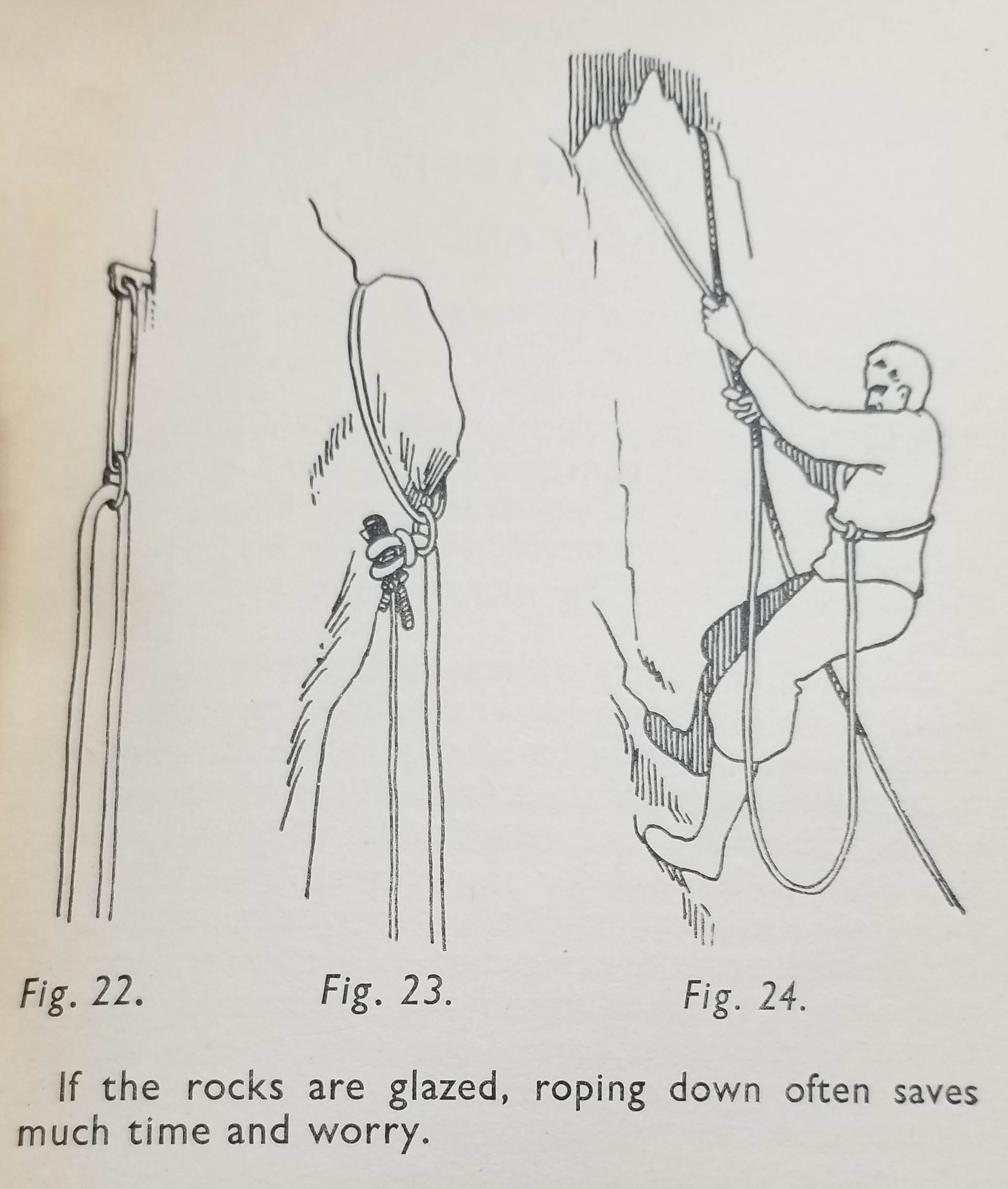

Illustration of a climber using natural protection methods to rope down from Alpine Climbing on Foot and with Ski by Ernest Wedderburn, 1937

Mountaineering involved technical rock climbing only as a means to reach the top of the mountain, and not, in those days, for its own sake and by the turn of the 20th century, most mountain climbers favored “natural protection,” which was securing rope to rocks or other natural features that could be found along the route. They used pitons nearly exclusively for climbing down and only then when the route down had become unsafe due to the sun setting or ice forming on rocks. This was especially true of UK mountaineers, who prided themselves on their ability to climb without the use of such aids.

Many mountaineers in those days believed that the use of artificial rock protection and aids, such as pitons, would lead to carelessness and were regarded as useless in the ascent of difficult routes.

Early pitons were iron spikes and had rings attached to one end through which mountaineers would secure their rope. However, those rings sometimes bent or broke under the weight of a mountaineer. Hans Fiechtl invented the modern piton in 1910, made entirely of one piece of metal with a hole (called the eye) in one end. This reduced the number of moving parts in the tool and made them sturdier and more reliable.

Illustration of piton use and placement from the Handbook of American Mountaineering by Kenneth Henderson, 1942

“In such cases, pegs to hammer in and anchor to are a remedy for our failures, our failure to carry on, to adjust the climb to the day-length, or to watch the weather. Their use then is corrective, not auxiliary.”

Angle piton with a ring

Illustration of proper piton technique from the Handbook of American Mountaineering by Kenneth Henderson, 1942

Pitons were mostly made of softer steel and iron that allowed them to conform to the shape of the crack when used, making it difficult or impossible to remove them from the rock when they were no longer needed. This method worked well in the softer rock of Europe and much of the US, and pitons were habitually left in place at the end of a climb.

However, leaving permanent marks on the landscape sat poorly with many climbers and soft pitons didn’t work well on longer routes where rock protection needed to be removed and used again. They also didn’t hold up well in the hard granite of places like the Yosemite Valley. In 1946 John Salathé, a climber and a blacksmith, used hardened steel to create pitons that could be removed from a crack and used again and again without getting bent or disfigured.

A lost arrow piton with sunburst design

The only problem with the harder pitons was that they often disfigured the rock. Since pitons are hammered into and out of rock cracks, and since the same cracks are often used over and over again, climbers were leaving their mark each time they inserted and removed a hard steel piton. The soft steel pitons weren’t much better at leaving a route unaltered, since they often had to be left in place. They can still be found in some routes.

“There is a word for it, and the word is clean.” – Doug Robinson, The Whole Natural Art of Protection, 1972

Yvon Chouinard, who had been making pitons through his Chouinard Equipment brand for several years by then, introduced the aluminum chocks in his 1972 Chouinard Equipment/Great Pacific Iron Works catalog. The catalog included two seminal essays on clean climbing; A Word by Yvon Chouinard and Tom Frost, and The Whole Natural Art of Protection by Doug Robinson. You can read them online here. This ethos changed American climbing forever and the piton was quickly replaced by equipment that could be easily removed and reused without damaging or altering the rock, first slings, nuts and chocks and later cams.

Pitons manufactured by Yvon Chouinard, arranged in order of their evolution.

Clean climbing methods proved to be much safer and easier to use than pitons, since pounding a spike into a crack with a hammer is time and energy consuming. Pitons are still used in some places where other types of protection aren’t an option, but these situations are rare.

You can check out some examples of pitons from our archival gear collection in the slideshow below.