LOWERING ERROR | Unclipped from Directional Rope

Red River Gorge, Kentucky

The following report is a preview of the upcoming Accidents in North American Climbing. The 2022 edition is at the printer and will be mailed this autumn.

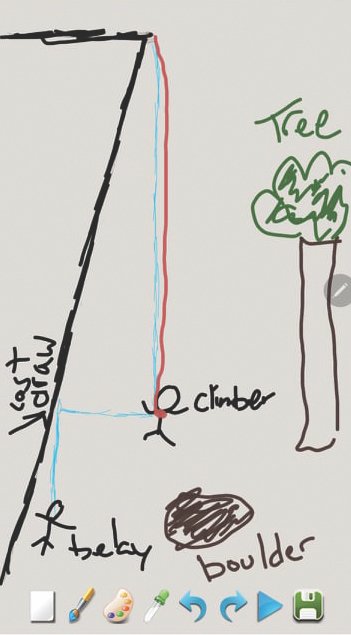

Logan Zhang, age 11 at the time, created this depiction of his own accident scene.

In March 2021, Logan Zhang (11) hit a boulder on the ground while cleaning a route in the Motherlode at Red River Gorge. Logan was using the cable car (a.k.a. tram) method to retrieve his draws, staying clipped to the belayer’s side of the rope, as is common when cleaning overhanging routes. The first draw on the route was a permadraw so the climber didn’t need to clean it. After he finished cleaning his own draws from the route, Zhang continued lowering with the belayer’s rope still running through the first draw. Before reaching the ground, he removed the tram draw from the belayer’s rope and fell, hitting a boulder below the climb. He suffered a minor head laceration.

ANALYSIS

It is common for climbers to use the cable car or tram method to clean their draws off steep routes. It is important to understand the system and the consequences of adjustments. This incident could have been avoided by keeping the tram draw connected until the climber had reached the ground. Removing the tram draw when the climber is out from an overhanging wall instantly introduces slack into the system and the climber will drop. Also, remember to knot the end of the rope to close the system; the tram method uses more rope than standard lowering.

Alternatively, Logan could have removed the tram draw when he cleaned the quickdraw at the second bolt and taken the swing from this location, if it was safe to do so. This situation is not uncommon. Many climbers choose to leave their own draw on the first bolt for safety or efficiency when cleaning overhanging routes. (Source: Ocean Zhang, father of Logan.)

Diagram by ANAC contributing editor Lindsay Auble

See “Know the Ropes: Cleaning Sport Routes” in Accidents 2021 for more great tips on cleaning steep climbs.

ANAC’s 75th ANNIVERSARY

The 2022 edition of Accidents in North American Climbing is the 75th annual educational publication of the American Alpine Club. Accidents debuted in 1948 as "Mountaineering Safety: Report of the Safety Committee of the American Alpine Club;” it evolved into “Accidents in American Mountaineering” in the 1950s.

The new publication originated as a result of “the startling increase in the number of mountaineering accidents which occurred during the summer of 1947,” according to the introduction. The report said “the number of persons interested in mountaineering, but lacking in climbing experience, has grown vastly,” citing the return to civilian life of thousands of World War II soldiers who received good but very brief training in mountaineering during their service.

Among the “factors of concern” cited in the report are several that ring true today:

• “Solo climbing appears to have spread alarmingly.”

• “So much spectacular publicity has been given to mountaineers and their climbs that many youngsters—and some older persons—see only the glamor, and fail to perceive that real success on a difficult climb connotes careful planning, hard work, proper technique and constant attention to the principles of safety.”

Other key takeaways in the 1948 edition now seem a bit archaic. For example: “Night climbing should be strictly avoided” or “Climbers should try to avoid placing a heavy man ahead of a very light man….careful consideration should be given to balance of weight on a rope.”

Nonetheless, few could argue with the 1948 report’s final words: “The most difficult climb done properly can be achieved more safely than an easy climb done carelessly.”

Three Accidents in 1947

Fred Beckey, courtesy of Dave O’Leske.

Wyoming, Teton Range: A rappeller on Mt. Owen was badly injured after his anchor failed: “A cut-and-dried case against using old rappel slings.”

British Columbia, Coast Mountains: In the Waddington Range, an avalanche killed one climber and injured three others, including Fred Beckey, who was already America’s most prolific climber of new routes in the mountains.

California, Yosemite Valley: A long fall on Higher Cathedral Spire broke the leader’s legs, but it could have been much worse, the report said, except for the belayer’s stalwart hip belay, the “resiliency and strength” of the party’s 7/16-inch nylon rope, and the fact that the leader had tied in with a bowline-on-a-coil with four wraps of the rope around his waist, potentially sparing him internal injuries.

Even 75 years ago, proper use of the best available gear saved lives!

The Prescription is published monthly by the American Alpine Club.