by Eric Rueth

Camp V (22,000 ft.) with Mashrabrum [sic] in the background. Photo, Third American Karakoram Expedition.

For the third and final installment of our pre-2018 Annual Benefit Dinner Americans on K2 wrap-up, we’ll take a look at the Third American Karakoram Expedition in 1953. It doesn’t seem possible to start this blog post better than the way Robert Bates started his article about the expedition in the 1954 American Alpine Club Journal,

“On 2 August 1953 all eight members of the climbing party of the Third American Karakoram Expedition, in excellent physical condition, were camped at 25,500 feet on K2 with ten days’ food. The summit of the second highest mountain in the world (28,250 ft.) rose less than 3000 feet above us. It was our hope to establish two men at Camp IX, at 27,000 feet or slightly higher, on August 3rd; and on the following day, if all went well, to thrust at the summit.”

The men high up on K2 were Dr. Charles Houston, Robert Bates, George Bell, Robert Craig, Arthur Gilkey, Dee Molenaar, Peter Schoening and Capt. H. R. A. Streather. After the 1938 First American Karakoram Expedition, Houston and Bates had been dreaming of returning to K2. Delayed by World War II and political conflicts between India and Pakistan they were finally able to return to K2 15 years later for a second attempt at the summit.

The optimism of reaching the summit by those eight men on August 2nd was met with a multi-day storm. At Camp VIII (25,500 ft.), the party was battered by heavy winds. One tent was completely ripped apart, forcing its occupants to seek refuge and residence in nearby tents. Even worse, the wind made keeping stoves alight impossible. Without being able to keep the stoves consistently lit, the party could not melt enough snow to stay hydrated.

After five days of being tent bound and becoming increasingly dehydrated, the storm began to lull. Now that it was possible to hear each other over the wind discussion of pushing higher up the mountain arose. But again optimism was met with disaster. When Gilkey emerged from his tent on April 7th, he immediately passed out.

Gilkey passed out from the pain that a charley horse had caused him. That charley horse turned out to be thrombophlebitis. Gilkey had blood clots in his leg. Getting Gilkey off of the mountain was now the main objective but hope still remained for an attempt on the summit. The party immediately broke camp to begin the descent, only to be turned back by the likelihood of an avalanche along the route. The storm raged on and the party bunkered down. On August 11th, the party’s hand was forced, Gilkey now had a clot in his other leg and more seriously in his lungs.

Capt. Streather at Camp III. Photo, Third American Karakoram Expedition

With the storm still raging, there was no other option than to descend. Any thoughts of a summit attempt were abandoned. Getting Gilkey down was now the only objective. Gilkey, who was unable to walk, was wrapped in his sleeping bag and the remnants of the destroyed tent; he would have to be lowered down the mountain.

The going was slow and required every ounce of strength and focus from the party. The route used to climb up the mountain did not work for descending now that Gilkey had to be lowered. Schoening and Molenaar led the descent by finding a suitable route. The rest of the party would belay Gilkey and each other.

On the steepest pitch of lowering, the storm obscured the line of sight and made vocal communication with others below futile. First Schoening and Molenaar disappeared into the storm. Then Craig escorted Gilkey while he was being lowered until he too disappeared. Streather descended to a point where he could see Craig’s arm signals and relay commands to the rest of the party belaying. Already physically exhausted by the task of lowering Gilkey and being battered by the storm, those belaying were in for a test. Streather turned to the group and shouted, “Hold tight! They’re being carried down in an avalanche!” The group, the ropes, and the anchors held fast. Craig, who was not tied into any ropes, grabbed the ropes lowering Gilkey and held on for the duration.

Following the avalanche, the party was absolutely exhausted. The party was close to the small ledge that served as Camp VII. Craig traversed to the Camp VII to gather himself after surviving the avalanche and to attempt to enlarge the ledge so the entire party could recuperate from the physically and mentally demanding day.

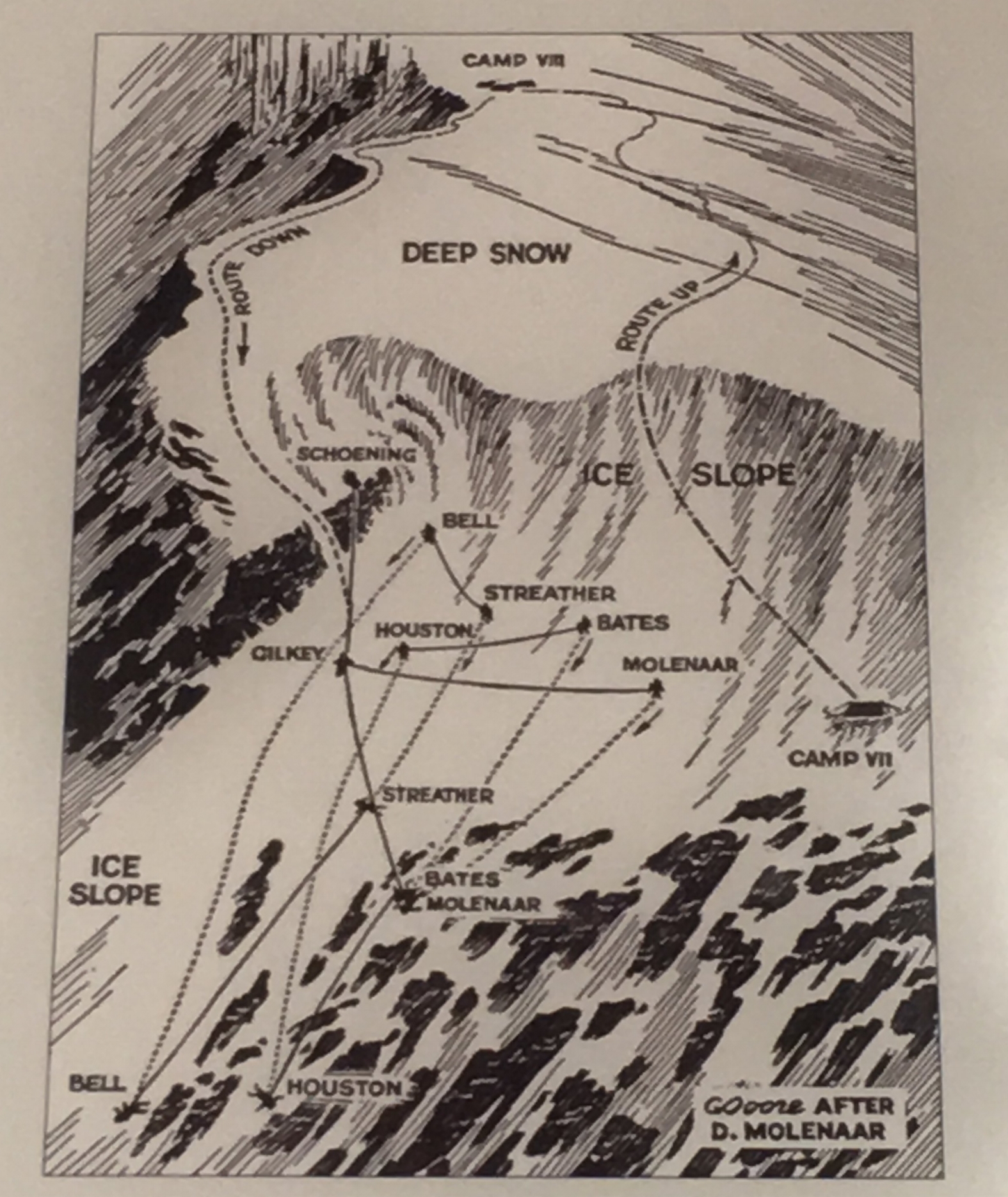

With Craig at Camp VII, the rest of party continued the extremely slow process of working their way towards the ledge. Bell was working his way over a difficult stretch of an ice gully when another catastrophic event occurred, Bell lost his purchase and started falling down the mountain. The hard ice prevented a self-arrest by Bell and Streather, who was tied into the other end of Bell's rope. The location of the pair when they fell set off a chain reaction that would send the entire expedition, except for Craig alone at Camp VII, down the mountain to the Godwin-Austin Glacier two miles below.

Only the entire expedition didn’t disappear over the edge of the mountain and fall two miles through the void. As members one by one were caught up in ropes and pulled from their feet, they tumbled and somersaulted downwards picking up momentum along the way until all of a sudden the rope grew taught. Schoening arrested the fall of his six companions in a moment that will forever be known as, “the belay.”

The entanglement that caused the catastrophic fall down the mountain also worked to save the expedition. Various injuries and lost gear resulted but the expedition suffered no loss of members.

This diagram by Clarence Doore follows an illustration by Dee Molenaar. It is one display at the American Mountaineering Museum.

Eventually making it to Camp VII the ledge still needed to be bigger before tents could be set up and the party could put the horrific day behind them. Gilkey was secured with two ice axes beneath a rock rib while the space was expanded. When camp construction was completed Streather, Craig and Bates went to retrieve him. Only, upon their arrival at the rock rib they found a bare slope. Gilkey and his anchors were gone, swept away by an avalanche.

The night that followed the horrific day would offer little rest. The party had been pushed to the limit physically, mentally, and emotionally and were now cramped together in two tents on a precarious ledge. The storm still raged on and Houston, who had suffered a concussion, would wake up in a state of confusion consequently waking up everyone else.

The next day the storm continued and so did the party. It took four days for the battered party to descend from Camp VII to Camp II. At Camp II, the party was met by porters who provided food and comfort after their heroic and tragic descent.

As they departed the mountain, the expedition built a large cairn memorial for Gilkey near the confluence of the Savoia and Godwin-Austen Glaciers. The memorial still stands to this day and has grown to be more than a memorial only to Art Gilkey; the Gilkey Memorial is now used to remember all who have perished on the Savage Mountain.

With the conclusion of the 1953, there had been three attempts made by Americans on K2. The first had been successful as a reconnaissance but failed to reach the summit. The following two ended without the summit being reached and tragic loss of life. Americans had paid a high price for their efforts on the mountain and it wouldn’t be until 1978 that the mountain would finally yield to Americans.

Read about the Second American Karakoram Expedition here.

Read about the First American Karakoram Expedition here.

*These blog posts were an attempt to sum up the American attempts on K2 prior to the successful expedition in 1978. Unfortunately they leave out a lot of the nitty gritty details and personalities of those involved. If your interests have been piqued you can read the full expedition reports in the American Alpine Club Journal at publications.americanalpineclub.org or if you're an AAC member you can checkout some of the many books about K2 in the AAC Library at booksearch.americanalpineclub.org.

By Eric Rueth