In early 1916, the Charter and By-Laws of the newly incorporated American Alpine Club were unanimously adopted by the officers and associated members of the Club. The original “Objects” of the Club were representative of the tone of the early 20th century, when alpinists and mountaineers were beginning to explore alpine regions and looking to the Poles for exploration, research, and “firsts.”

Fifty years after the Club’s formal incorporation, research was an official agenda item in all Board of Director meetings. At the May 5, 1966, meeting, the Board voted to approve a grant for snow sample collection in the St. Elias Mountains of Alaska:

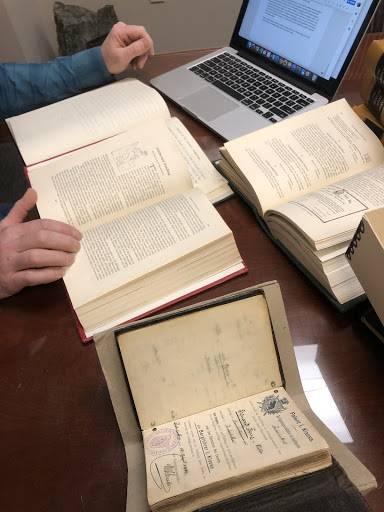

The AAC-funded Icefield Ranges Research Project, continues to inform modern researchers looking into glacial retreat and climate change.

As climbing grew in popularity, the AAC broadened its mission to encompass the full scope of climbers and climbing environments. Throughout these shifts, we have maintained our support for research and scientific exploration of high alpine environments and treasured climbing landscapes. Today, research grants continue to be a critically important program at the Club. We have more than 100 years’ worth of AAC-funded research into alpine landscapes. This body of work provides a bedrock for future researchers to build on, particularly with regard to high alpine and glacial landscapes.

Our climate is rapidly changing and causing potentially irreversible damage to alpine environments and every year we see a greater number of proposals for research in these subjects. Our historical and ongoing funding of this work, speaks to our belief in evidence-based advocacy and our commitment to create positive change in the world by supporting this research.

Current State of Research Grants

In 2016, we supported a research team’s effort to measure ice composition and thickness on the summit of Denali, through snow and ice core samples and the use of ground-penetrating radar. A member of the AAC’s Climate Change Task Force, and Director of Academics and Research at Juneau Icefield Research Program (JIRP), Seth Campbell, PhD., covered the expedition and challenges on his personal blog. He explains in greater depth their research process and findings. Plus, he has some great photos of researchers in action!

Funding from AAC research grants enabled the team to summit Denali and record baseline data from the highest peak in North America, which previously hadn’t been technologically possible. This research lays the groundwork for continued study and analysis of how alpine environments are changing. We can’t know for certain how today’s research will help determine the future of our planet, but we remain committed to working with scientists, researchers, climbers, and citizens regarding the “promotion and dissemination of knowledge.” The work happening now is invaluable for future scientists, just like the findings of the Icefield Ranges researchers in the 1960s informs modern analyses. Additionally, research-backed climate science informs the Club’s policy positions and provides a sound rationale for local and federal laws aimed at protecting alpine environments.

Research funding is still built into our endowment, and we have expanded the program by partnering with organizations like the National Renewable Energy Lab, Rockridge Venture Law, FourPoints Bars, and Kavu. These partnerships allow us to support more researchers and increase our average award amount. But it still isn’t enough. There is a growing need for further sound research into our changing climate and human impacts on the climbing landscape. That’s why we’re looking for more partners to help us support this work.

Moving Forward with Research Grants

Our recent national climber survey found that “88% of climbers believe climate change is happening now and is mostly caused by human activities.” At the same time, more people are recreating outdoors and causing their own impacts to these different ecosystems. Our AAC-funded researchers are helping us understand the very real impacts of climate change and increased human activity on these landscapes.

We awarded funds for glacial research more than fifty years ago and are committed to continue funding these projects that help determine the scale of climate change and the ongoing effects of pollution, glacial retreat, and environmental degradation due to overuse. In addition to climate science, we fund research that looks at the sociological impacts of climbing on local and global levels.

Looking ahead, we hope our research grants will fund work that directly impacts many areas of the Club. We look to fund research across disciplines, to better understand the climate, climbing landscapes, land access, human interactions, health and wellness, and more. Throughout our Club’s history, we have stayed true to our original objective of “the study of the high mountains of all America.” More than 100 years later, we embrace that directive and are proud to support a more comprehensive understanding of all aspects of the climbing universe.

Check out our website for more information about:

AAC’s Research Grants

2019 Research Grant recipients

AAC’s Climbers for Climate initiative

AAC’s Policy and Advocacy work

Email [email protected] with questions and to learn more about how to support this important work!

Caroline Bridges, AAC Grants Manager