We are entering the prime season for climbing on the East Coast, so this month we’re featuring an incident that took place on Moss Cliff in upstate New York. Don Mellor, climbing guide and author of American Rock and Climbing in the Adirondacks, calls Moss Cliff “among the most appealing rock walls in the Northeast." Such an attractive crag has its inevitable share of mishaps. The following report appears in the 2023 edition of Accidents in North American Climbing, which is being mailed to AAC members this month, and has been expanded here with more information from the ranger involved in the rescue.

Guidebook author Don Mellor calls Moss Cliff “…the most Adirondack of all Adirondack crags.” Hard Times (5.9+) is drawn in red. The stranded climbers were stuck at the pitch-two belay. Photo by Jim Lawyer.

STRANDED | Stuck Rappel Ropes

Adirondacks, Moss Cliff

At 6:30 p.m. on October 16, 2022, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) rangers received a call from two climbers who were stranded on Moss Cliff in Wilmington Notch within Adirondack State Park. Moss Cliff is a 400-plus-foot face with a 30-minute approach that involves fording a small river.

The two climbers had topped out on a four-pitch trad climb called Hard Times (5.9+) and had completed their first double-rope rappel from the bolted rappel station at the top of the final pitch. When the climbers went to pull their ropes after the first rappel, the rope would not budge. After repeated attempts to pull the ropes down, the climbers considered themselves to be stranded and used a cell phone to contact rangers.

DEC ranger Robbi Mecus was able to talk to the subjects via cell phone and instruct them. She determined that the subjects still had both ends of the rope, and that it would be possible for one of them to use prusiks to climb the ropes back to the anchor. However, the climbers did not have prusik loops and were unfamiliar with techniques for ascending a rope. Mecus was able to coach the climbers by phone on how to use their sewn slings as prusiks. She then instructed them to create two prusik loops: one short one attached to the harness and one long one as a foot loop. She also instructed them to tie in to the ropes directly every few feet as a backup should the prusik attached at the waist fail. The climbers completed one round of practice with Mecus on the phone, and then one of them prusiked to the top of the climb to free the rope from the crack in which it had been stuck.

Mecus instructed the subjects to pull the knot joining their two ropes down past the obstruction and place a nut in the crack to prevent another stuck rope. They were able to retrieve their ropes and finish their descent. She stayed on the phone with the subjects while she herself approached the cliff to ensure the subjects were following her directions. The subjects had left their headlamps in their packs at the base of the cliff, not expecting to be caught in the dark. This oversight exacerbated the situation. Mecus then assisted the subjects across the west branch of the Ausable River and back to the trailhead.

ANALYSIS

More people are learning to climb in the gym or on sport routes. Thus, they can become stronger climbers much faster than in the past, without learning the foundational skills associated with outdoor traditional climbing. These climbers were very capable, successfully climbing a four-pitch 5.9+ trad route, but were not familiar with the relatively basic rope ascension techniques they needed to ascend and free the rope.

Investing in self-rescue skills is an important part of transitioning from gym to crag. These can be learned through mentorship (informally or with a guide), through self-rescue courses, or even by reading a book or watching YouTube videos on self-rescue. A few minutes invested in learning and practicing how to ascend a rope with prusiks would have prevented the need for the rangers to be called. The climbers were right to have brought a cell phone and used it to call for help. Had they been unable to receive help by phone, the climbers’ situation would have turned significantly more dire, as they would have been stuck several hundred feet up the face for the night or longer.

As this incident demonstrates, you never know when you may be unexpectedly delayed. The climbers in this incident did not have headlamps and were unprepared to be out after dark. As a general precaution, always bring a headlamp when multi-pitch climbing. Stashing a small headlamp in the bottom of a chalk bag is a great way to ensure you always have one with you.

(Sources: New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Forest Rangers and the Editors.)

FaceTime and SARTopo

Mecus used FaceTime to communicate with the climbers and visually demonstrate techniques, as she has on other rescues. She recalls one such incident: “A hiking party with an injured individual (dislocated finger) was asking for a ranger to hike out to them. I was able to look at the injury (via FaceTime) and with a good interview determined it was dislocated. I instructed them how to reduce the dislocation, sling and swath the arm, and walk themselves out. Pretty simple.”

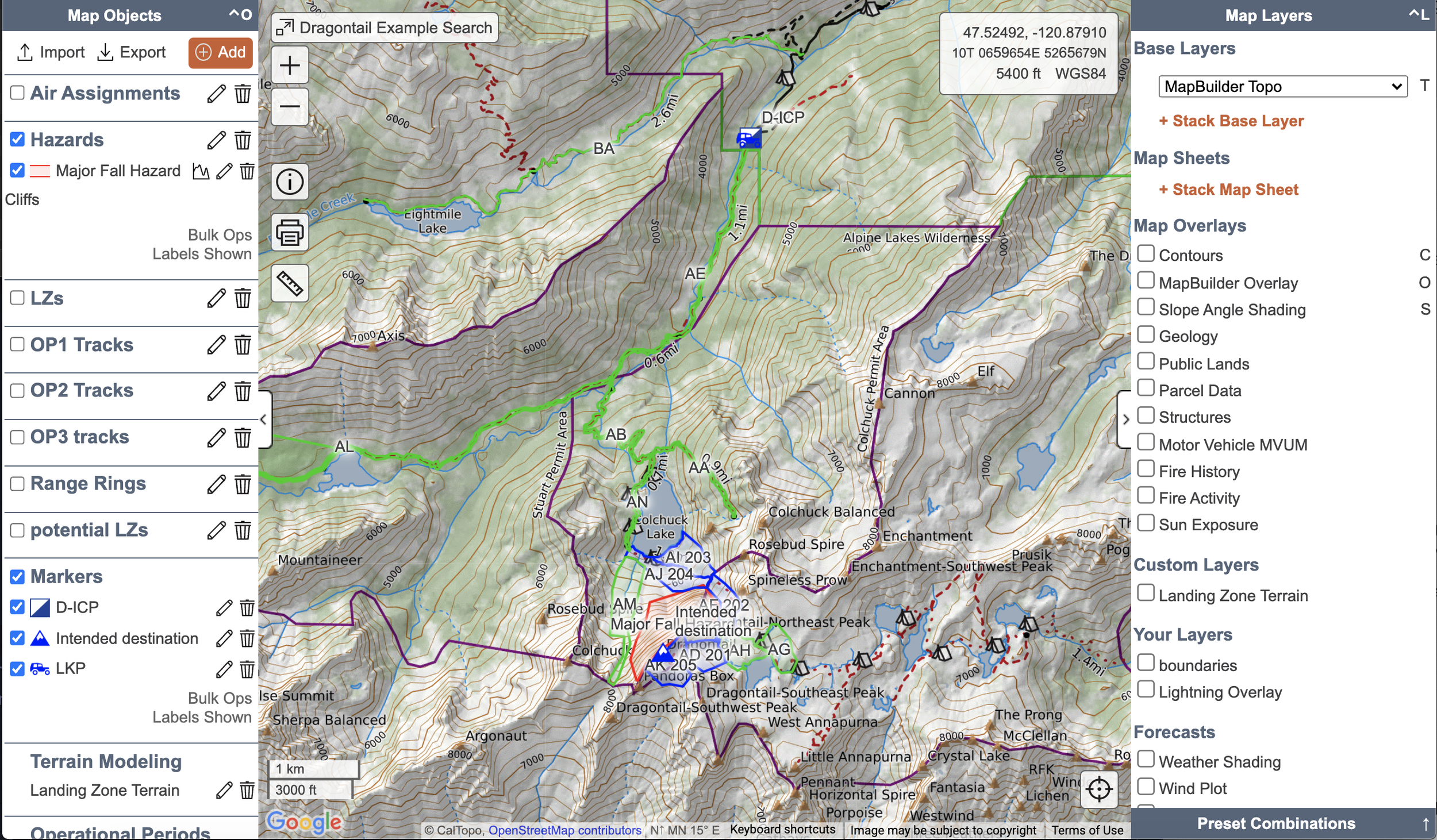

Mecus uses other technologies to help people get themselves out of trouble in the mountains and woods—technologies that help conserve precious ranger resources. She says, “With better cell phone coverage comes the ability to send a lost person a link to a SARTopo application. This allows us to see them on a map as they move.” SARTopo, a version of CalTopo, is a widely used, collaborative online and offline mapping tool; the program name SARTopo is being phased out in favor of CalTopo.

For background on SARTopo (CalTopo), click here.

SARTopo is a web-based version of CalTopo with SAR-specific enhancements, including a variety of map layers and overlays.

For a consumer overview of SARTopo (CalTopo) and a how-to tutorial, click here.

DEC ranger Robbi Mecus says, “Improved cell coverage obviously has impacts on our ability to talk to stranded or injured climbers.”

While cell service has improved in recent years deep in the Adirondacks, you can’t count on a phone in remote areas and should still carry an inReach or other satellite-based communication device. Nonetheless, Mecus says, “Within the past seven or eight years, certain spots on Wallface, our tallest and most remote wilderness cliff, can hit a cell tower. Wallface is six miles from the nearest trailhead and 800 feet tall. A few years ago, we had a seriously injured climber hanging on pitch two of an eight-pitch 5.8 after taking a 60-foot fall. Their friend on the ground was able to find cell service and call dispatch. We were able to insert myself and a volunteer climber via helicopter at the base, climb up to the party, package and lower the subject to the ground, and perform a helicopter hoist extraction. The climber was in the hospital within five hours of his accident. Without the improved cell coverage, he would’ve been hanging suspended on the cliff all night. I'm not sure he could've survived his injuries.”

Read the ANAC report from the Wallace incident here.

Join the Club—United We Climb.

Get Accidents Sent to You Annually

Partner-level members receive the Accidents in North American Climbing book every year. Detailing the most noteworthy climbing and skiing accidents each year, climbers, rangers, rescue professionals, and editors analyze what went wrong, so you can learn from others’ mistakes.

Rescue & Medical Expense Coverage

Climbing can be a risky pursuit, but one worth the price of admission. Partner-level members receive $7,500 in rescue services and $5,000 in emergency medical expense coverage. Looking for deeper coverage? Sign up for the Leader level and receive $300k in rescue services.