May Perez Climbing Arrow (5.8). Photo by Eric Ratkowski.

By Marian (May) Perez

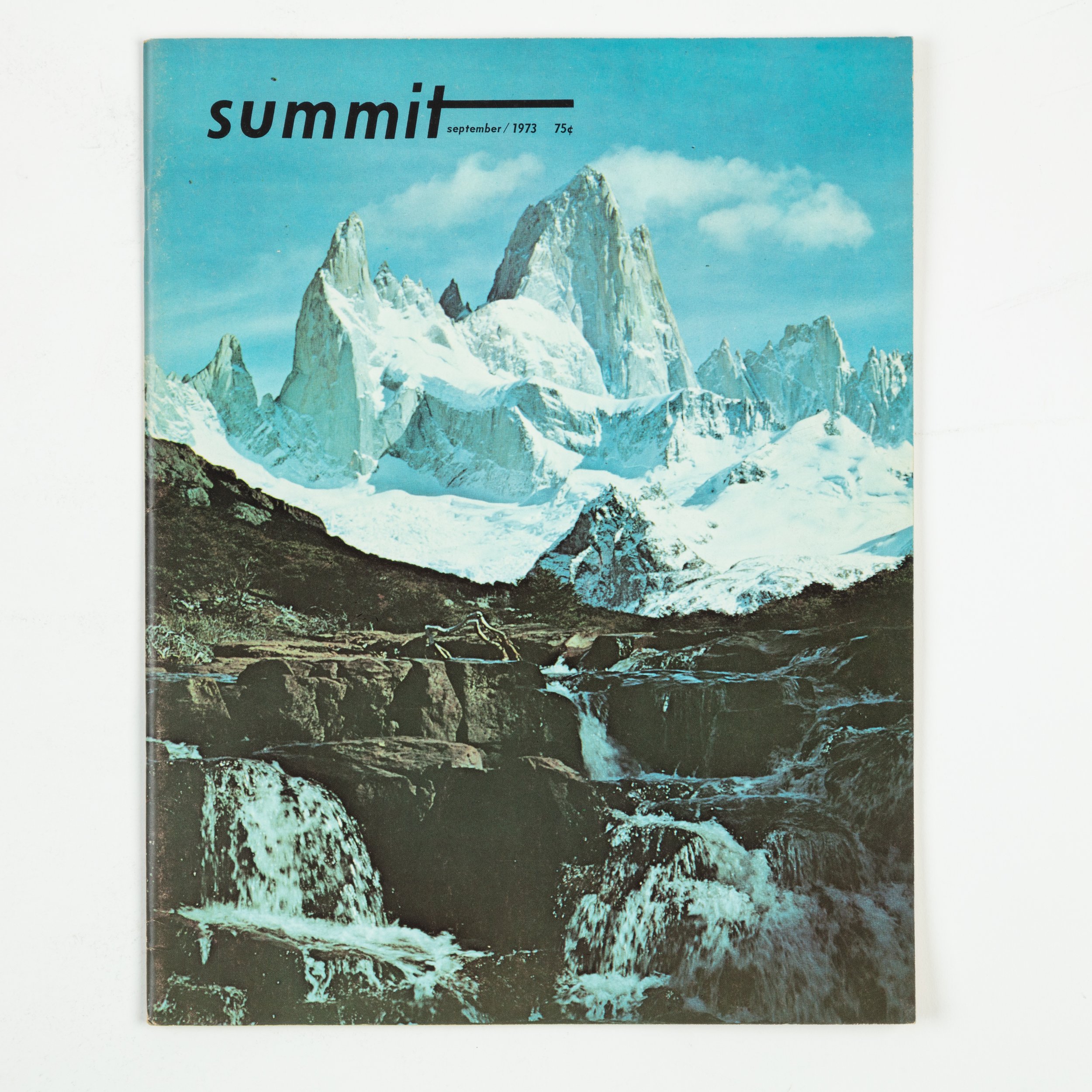

A place I look forward to getting to, another place I call home. I sometimes drive through local roads outside of New Paltz, most of the time I drive up the thruway from New Jersey to go upstate. Jamming to my favorite tunes on repeat with joy or crying my heartache away from emotional pains. Once I see the stretch of windy road on Rt 299, passing by the farms and artwork, the interesting sculpture at the four way stop that not only indicates I’m getting closer, but also prompts the first appearance of the massive being known as the Shawangunks. I pass through the AAC campground to reminisce and surprise my close friends, a safe place for me to exist. A place where I’ve lived in my car and woke up next to the being called the West Trapps. A place where you look into the distance and see tiny dots of color climbing up the wall like ants making their way with their daily discoveries. A place where if you listen deep enough, you can hear the echoes of folks letting their partners know “Off belay!”

At the sight of apple trees and the random billboard, my body wakes up. I know what I’m about to see and I know where I’m about to go. This must be the place, exit 18 to New Paltz, NY, home of the Shawangunk Mountains and home to me, where I want to be.

I drive through town with my windows down, taking in all the quirky things that make this place special. Making stops at my favorite gear shop, Rock and Snow, and grabbing the best coffee and tea in town at The Ridge Tea and Spice. I say hi to all my friends, grounding myself after a long drive and filling my heart cup knowing people care about me.

Vanessa and Hannah on Cascading Crystal Kaleidoscope (CCK) (5.8 PG13). Photo by May Perez.

I look up to spot the Dangler Roof. Close my eyes and daydream about sitting on the GT Ledge on Three Pines or Something Interesting, looking out in the valley trying to find the campground and all the land surrounding it, thinking about how small we humans actually are. We might not have the biggest mountains, but the feeling is the same I’ve had looking out into Yosemite Valley. The beauty of being surrounded by so much, and still so much to see. Or the privilege to be on a 9,000 ft long cliff in the middle of the day.

I open my eyes to find myself on the GT Ledge, realizing I’ve been present the whole time. It’s sunset and there’s still so much light on the cliff, except the darkness that hides in the trees below me. It might seem like we’ve been benighted, but the quartz conglomerate glows for us a bit longer to finish up Crystal Cascading Kaleidoscope (CCK) 5.7+, one of the wildest traverses of the grade. I follow my leader after they send and get ready to tip toe my way over to the big flake, trusting the polished feet and jamming my way up the #1 hand crack, up further to the crimpy ledge, back over to my partner, stoked to see me pull the last moves over the top of the cliff. We enjoy the last bit of light and share gratitude to the day and how we overcame what was presented to us, wild adventure no more than 400 ft below us.

This must be the place, the place I like to call home, where I want to be.