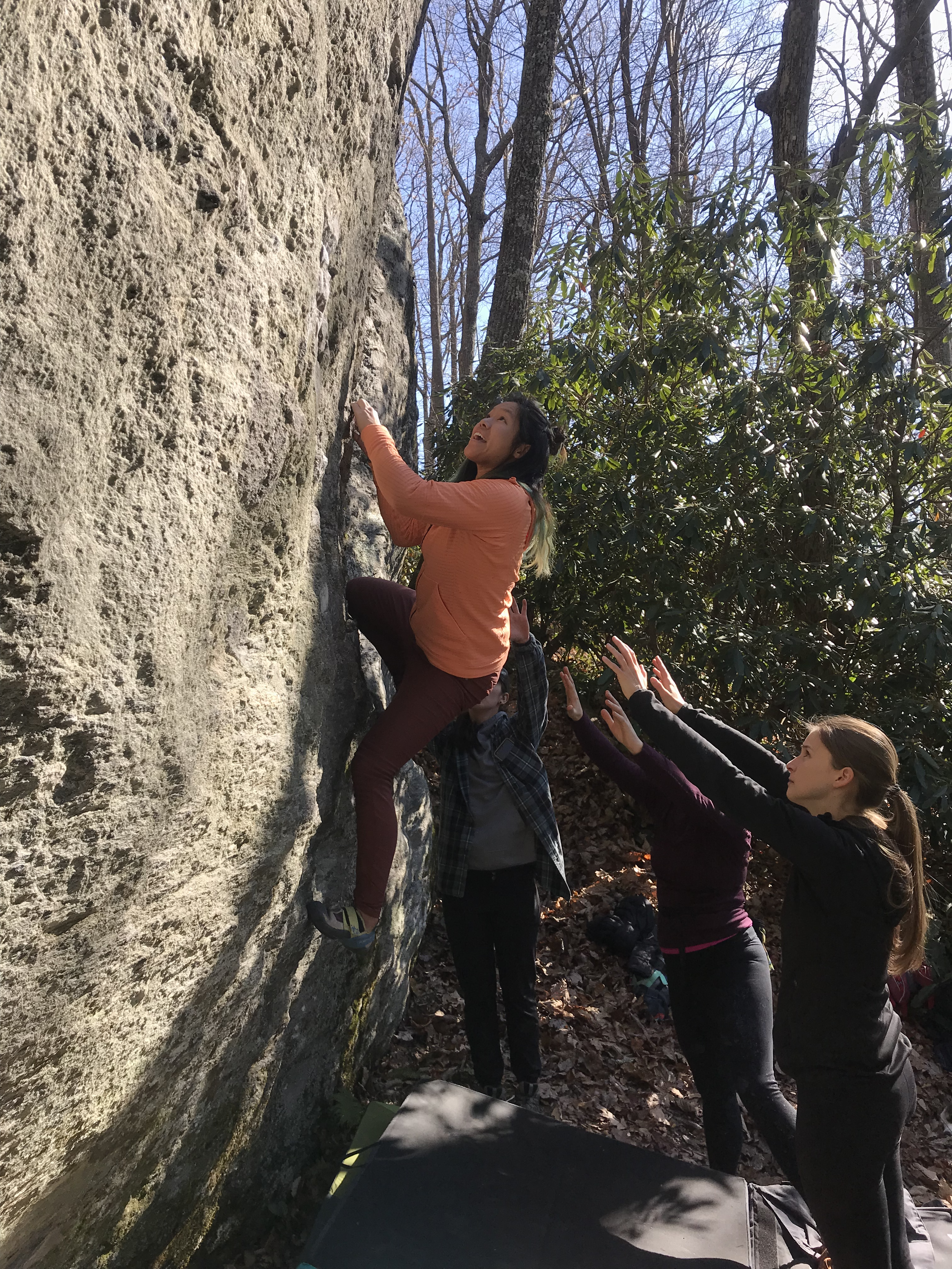

The AAC Triangle Chapter nourishes a strong female climbing community.

PC: AAC member Anne McLaughlin

Grassroots: Unearthering the Future of Climbing

By Sierra McGivney

A woman's place is on lead. No longer is climbing “an old boys’ club.” This is true now more than ever. The future of climbing is expanding beyond traditions of the past at a rapid pace.

In North Carolina, AAC member Anne McLaughlin created a network of women climbers aiming to empower those who identify as female. What started as a Women's Climbing Night evolved into a network of women aged 20-70 who are all bound together by their love of climbing.

“We called ourselves women’s climbing night until this year. We realized we were more than a night, we were a network,” says McLaughlin.

McLaughlin yearned for a women’s climbing community in North Carolina. Although North Carolina has a strong climbing community, there was not a strong female presence.

PC: AAC member Anne McLaughlin

Oftentimes women are introduced to climbing by male partners or friends. Although there is nothing inherently wrong with this, it does reflect the reality that the majority of educators, mentors, and guides are men, positions that allow for knowledge-sharing and decision-making that shape the culture of climbing. In addition, because of societal pressures, someone who identifies as a woman may feel as though they have to prove themselves in front of a male climbing partner. When women climb with other women that pressure can often disappear, and they can focus on the climb at hand.

Jane Harrison, a friend of McLaughlin’s had run a women’s climbing meet-up when she was living in Oregon. She approached McLaughlin about starting one in the area. Together they began to devise a plan to create a Women’s Climbing Night for their local North Carolina community.

The key was to keep the event casual and have a core group of women who attend, organize, and facilitate. Instead of having a one-off event, they opted to have a consistent two nights a month blocked off for women’s climbing. Establishing rapport and consistency with their community encourages participants to have a long-term relationship with climbing. Harrison and McLaughlin began hosting meetups at their local gym, Triangle Rock Club in January of 2018.

“Ever since then, we've just had more and more people joining up,” says McLaughlin. “Right now I run the email list and we have over 260 women.”

PC: AAC member Anne McLaughlin

Cory Johnson, the AAC Triangle Chapter Co-chair, got involved quickly with the Women’s Climbing Network (WCN). She discussed with McLaughlin how the AAC could partner with them. Now, the AAC Triangle Chapter supports the WCN by providing access to their gear closet for outdoor events and promotes them on the Triangle Facebook page. Johnson encourages women who attend the Triangle Chapter skills clinics to get connected with McLaughlin.

“So many of the women who've joined our group came to it through taking a clinic through the American Alpine Club Triangle Chapter,” says McLaughlin.

In the North Carolina climbing community, there is a strong desire to find good consistent partnerships and mentors. By creating a strong women’s climbing community that removes hurdles like gym to crag transition, McLaughlin has provided a safe climbing environment that empowers women.

“There is a hunger out there for women to climb with other women and learn from other women,” says McLaughlin.

PC: AAC member Anne McLaughlin

McLaughlin wasn’t always the strong trad crusher she is today. Her first time climbing left her disappointed and discouraged. At the time she was a graduate student at Georgia Tech and had signed up for a beginner outdoor climbing class. No prerequisite needed. The group piled into a van and drove out to Sand Rock, Alabama, a crag that McLaughlin would come to know well over the subsequent years. Sand Rock is known for its beginner-friendly toprope jug routes —full of horns, suitcase handles, and chicken heads—as well as crimpy face climbs and thin crack lines. Sport routes run parallel to difficult trad routes. There are even a couple of good bouldering problems—some even describe it as "the Southeast's most underrated bouldering area,” according to Mountain Project.

McLaughlin was the only woman in the group on her first trip. The guides set up one of the notorious overhung juggy 5.6 climbs. The moves resembled a pull-up. Each tug upward makes the climber look and feel strong, while being a relatively easy route. But it was not “easy” for McLaughlin. She stood at the base, trying repeatedly to pull herself up with no success. She thought: I’m worse than everyone here. I’m failing. I’m just not a climber.

Around the corner was a multitude of slab routes. Routes that might have favored McLaughlin's strengths. But McLaughlin had only been presented with one version of what climbing could be.

PC: Adriel Tomek

“Having that experience, [you realize] you have to set up people for success and play to people's strengths,” says McLaughlin. “Observe what they can do and what they are having trouble with, and tweak their opportunities to ensure they have an excellent first experience, especially outside.”

A couple of years later during an internship in Florida, McLaughlin tried climbing again. Her supervisor, Gwen Campbell, was a climber in her 50s and brought her to the local climbing gym in Orlando. Campbell was McLaughlin's biggest cheerleader. Every move McLaughlin made was followed by a cheer and shout of excitement.

“She introduced me to climbing and I absolutely loved it,” says McLaughlin.

Now, McLaughlin is the cheerleader. Although education is not the point of their trips, McLaughlin gives participants an opportunity to learn. She spends the day showing anyone interested how to clean sport routes, rappel, and flake the rope. One woman, Rachel, who is primarily a gym climber, began going to their outdoor events. McLaughlin anchored into the top of a climb at Pilot Mountain while Rachel cleaned the anchor. The sun beat down on the two of them as Rachel cleaned the anchor first with McLaughlin’s instruction and then with McLaughlin just watching to make sure she was safe.

Later McLaughlin received an email from her, explaining that she had practiced cleaning the anchor and was able to take her friends out and teach them. She had felt empowered by McLaughlin's instruction and was grateful.

“That made my day,” McLaughlin says with a smile.

PC: AAC member Anne McLaughlin

The goal of the WCN is to connect and empower women, arming them with knowledge so they can advocate for the climbing they want to do, and make informed and safe decisions for themselves in the mountains. Participants are encouraged to find climbing partners and friends to meet up with outside of WCN nights and events. Independence within climbing allows women to make decisions in the mountains confidently, a skill every climber should have. The network provides an environment for women of all ages to grow, learn, and connect.

“If you see it, you can be it,” says McLaughlin.