National Park Service rangers rescuing the fallen climber from Mt. Shuksan. NPS Photo

The Prescription - January 2021

ANCHOR FAILURES IN THE MOUNTAINS

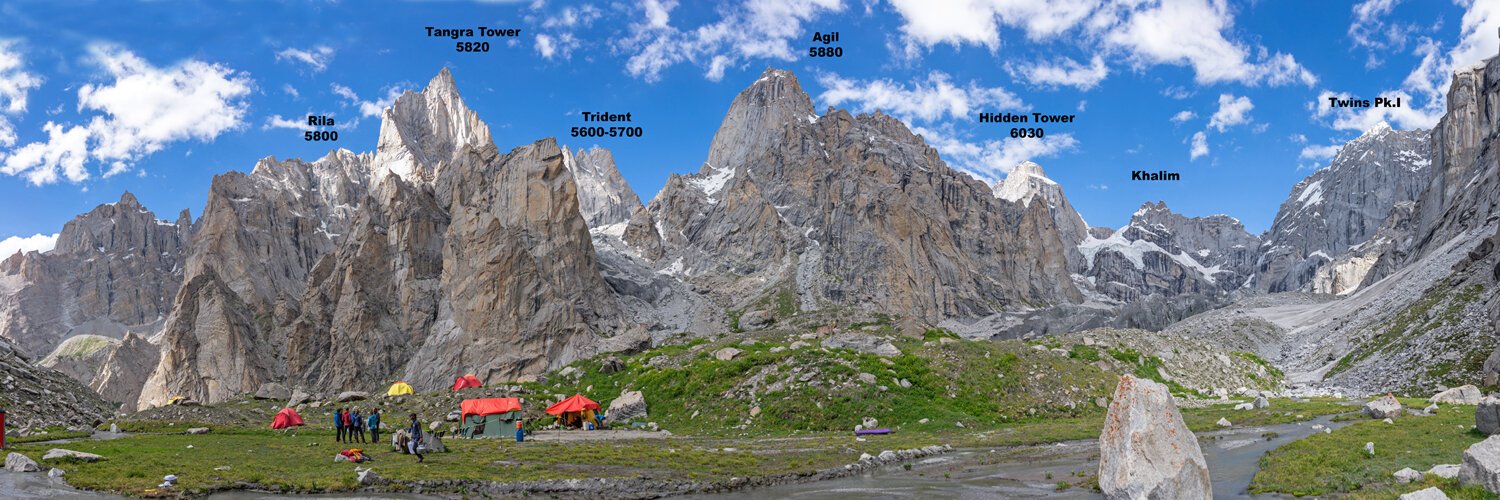

North Cascades National Park, Mt. Shuksan, Sulphide Glacier Route

On July 19, 2020, a party of three climbers was descending Mt. Shuksan after summiting via the Sulphide Glacier route. The party was rappelling the standard descent route on Shuksan’s summit pyramid. They reached a flat ledge and found an existing anchor consisting of a single loop of red webbing around a rock horn. After pulling the rope from the previous rappel, one of the climbers, a 28-year-old female, began to rig the second-to-last rappel of their descent. She threaded the rope through the anchor, rigged her rappel device, and began to weight the anchor. At this time, the rock horn failed, and the climber fell about 100 feet. The other climbers were not attached to the anchor when the failure occurred. The climber came to rest in 3rd- and 4th-class terrain, suffering an unspecified lower leg injury.

The party activated an inReach device to request a rescue, and the remaining two climbers were able to downclimb to the fallen climber’s position and provide basic medical care. At 5:30 p.m., National Park Service rangers arrived on scene via helicopter, and a short-haul operation was performed to extract the injured climber. The rest of the party was able to safely exit the mountain on their own.

ANALYSIS

In an interview with the party, the climber stated they were in a hurry due to the lateness of the day and they were tired from attempting a car-to-car climb of this long route (6,400 feet of elevation gain). The climber stated that at this rappel station they did not assess the integrity of the anchor, as they had been doing previously. This decision was influenced by time, fatigue, and the assumption the anchor would be strong, like the other anchors they had just used for rappelling.

When rappelling, it is imperative to assess the integrity of every anchor before weighting it. Inspect the entire anchor material, especially the less visible back side of the anchor, to be sure it is not chewed, weathered, or otherwise damaged. It is not uncommon to encounter structurally unsound rock in the North Cascades; if possible, test all anchors with a belay or backup before rappelling, and back up the anchor until the last person in the party descends.

It is possible the horn that failed was not one of the standard descent anchors on Shuksan’s summit pyramid. During multi-rappel descents, it is not uncommon to rappel past the standard anchor or to spot an anchor from above and head toward it, thereby missing the optimum anchor. When the descent route is the same as your climbing route, try to note and remember the position of the standard rappel anchors as you climb. (Source: North Cascades National Park Mountaineering Rangers.)

A very similar rappelling accident on Mt. Shuksan’s summit period was reported in the 1992 edition of ANAC.

RAPPEL ANCHOR FAILURES: A COMMON THEME IN ANAC 2020

The 2020 edition of Accidents in North American Climbing reported an unusually high number of rappel anchor failures: six in all! Half of these resulted in fatalities.

Just after this climber began a short rappel on Nishelheim’s northwest ridge, the sling came undone and she fell, fortunately without serious injury.

Two of the six rappel anchor failures in ANAC 2020 involved inadequate anchors built by the climbers; the pieces pulled out of the rock when weighted. In a third case, the climbers built their own anchor and then the rock pillar in which their cams were placed shifted, causing the cams to pull out. Three of the incidents were very similar to the one reported above. Climbers found an in situ cord or sling, which broke or came untied when a rappeller weighted it:

• Mendenhall Towers, Alaska: A worn cord connecting two fixed pieces broke under load.

• Evolution Traverse, California: A weathered cordelette snapped, even though one climber in the party had already used it.

• Niselheim, British Columbia: An in situ sling wrapped around a rock horn came loose when a rappeller failed to inspect it before weighting the ropes—the “knot” joining the two ends of the sling was completely inadequate.

Online forums are filled with photos and discussions of the best way to rig rappels from bolted anchors. But failures of such anchors are extremely rare. The types of incidents described here—especially the failure of rappel anchors built with rock horns, boulders, or weathered slings on mountain routes—are far more common. The lesson is crystal clear: No matter how tired you are, how dark it is, or how quickly the weather is deteriorating, every rappel anchor found in place while descending must be carefully inspected and/or tested before it can be trusted.

THE SHARP END: TURNING THE TABLES

After five years of hosting the Sharp End Podcast, it’s Ashley Saupe’s turn to be interviewed. Listen as Steve Smith at Experiential Consulting turns the tables on the podcast creator and interviews her about some incidents she's had in the backcountry, how she's managed them, and why she is inspired to continue producing this podcast for her listeners.

MEET THE RESCUERS

Neil Van Dyke, Search and Rescue Coordinator, Vermont Department of Public Safety, and member of Stowe Mountain Rescue

Years volunteering with your team: 40

Home areas: Smugglers Notch and Lower West Bolton. But I spend more time skiing (backcountry, alpine, or Nordic), hiking, and canoeing than I do recreational climbing.

How did you first become interested in search and rescue?

It was an opportunity to combine my interests in first aid and emergency response (I was a volunteer firefighter and EMT) and recreating in the outdoors. It was a natural fit. There were no local SAR teams at that time, so I helped start one!

Personal safety tip?

It’s hard to pick just one, but for me the most important is having really good situational awareness, knowing your limits, and understanding when to turn around and come back another day. Most people get in trouble because they push limits, which can be either a conscious decision or one made unwittingly due to a lack of situational awareness.

How about your scariest “close call”?

September 11, 1993. Our team was responding to Hidden Gulley in Smugglers Notch to assist a father and son who had gotten cliffed out. I climbed up to a ledge about 100 feet below them and was belaying my partner up to my position. The rock was really nasty and rotten, but I put a sling around a large bulge that I thought would be okay as an anchor. Unfortunately, that whole piece separated from the face and took me with it. I fell about 60 feet and was sure it was “all over,” but survived with a bunch of broken bones and a punctured lung. I still receive the occasionally ribbing from colleagues for trying to direct my own rescue.

What are your biggest concerns for this winter season?

Like many areas of the country, we are concerned in Vermont about what looks to be a large influx of new backcountry skiers. While we saw this to some degree with people flocking to the outdoors last summer during COVID, the consequences of something going wrong in the winter are clearly much higher. We shouldn’t be afraid to welcome new users to the sport, but there are definitely concerns that some will not be properly equipped and prepared. We’ve had some good discussions among the local ski community about watching out for each other and doing what we can to gently mentor newcomers to the backcountry when we encounter them.

What would you say to people interested in learning more about search and rescue?

Reach out to your closest SAR team to find out more about how they operate and what they are looking for in members. You can also check with the government agency that has jurisdiction for SAR in your area. For most teams, having really solid all-around outdoor skills is critical—we always tell prospective members that we can teach the technical rescue skills needed, but we can’t teach them how to be comfortable and effective while working long hours outdoors in adverse conditions.

Share Your Story: The deadline for the 2021 edition of Accidents in North American Climbing is not far off. If you were involved in a climbing accident or rescue in 2020, consider sharing the lessons with other climbers. Let’s work together to reduce the number of accidents. Reach us at [email protected].

The monthly Accidents Bulletin is supported by adidas Outdoor and the members of the American Alpine Club.