Some quick ideas so you don’t have to spend Halloween dressed as yourself.

The Secret History of the Ice Axe

Mountaineering Boots of the early 20th century

A tale of horror and woe

by Allison Albright

Modern mountaineering boots are made to be comfortable, lightweight, insulated and waterproof. They're constructed of nylon, polyester, Gore-Tex, Vibram and involve things like "micro-cellular thermal insulation" and "micro-perforated thermo-formable PE." This technology costs anywhere from a couple hundred dollars to over $1000 and makes it much more likely for a mountaineer to keep all their toes.

We didn't always have it so good.

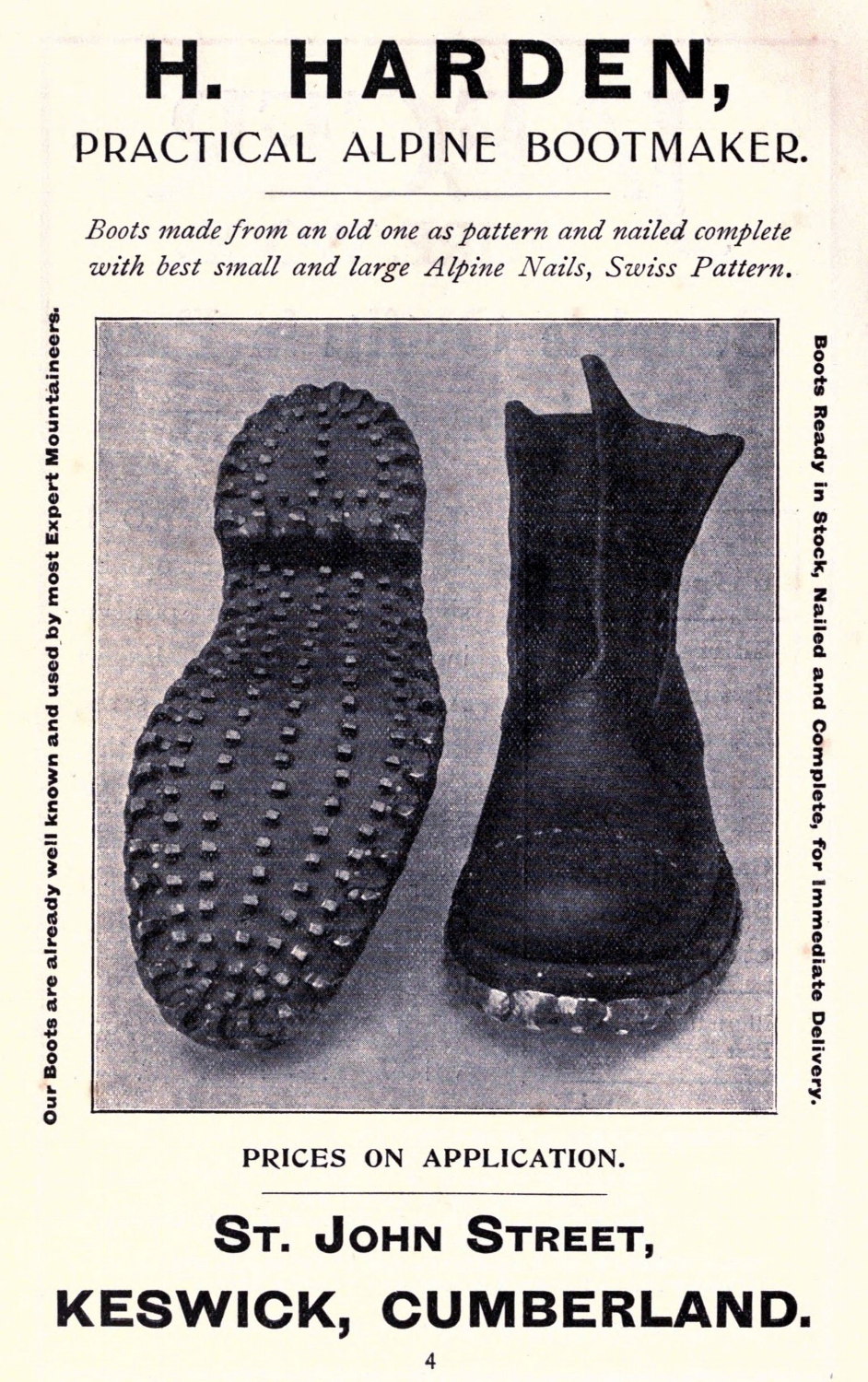

Mountaineering boots circa 1911.

By H. Harden - Jones, Owen Glynne Rock-climbing in the English Lake District, 1911, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9433840

Early mountaineering boots were made of leather. They were heavy, and to make them suitable for alpinism it was necessary for climbers to add to their weight by pounding nails, called hobnails, into the soles.

“The very best boot is without a doubt the recognized Alpine climbing boot. Their soles are scientifically nailed on a pattern designed by men who understood their business; their edges are bucklered with steel like a Roman galley or a Viking’s sea-steed. No doubt they are heavy, but this slight inconvenience is forgotten as soon as the roads are left.”

Tricouni nails were a recent invention in 1920 and could be attached to mountaineering boots to provide traction. They were specially hardened to retain their shape and sharpness.

Illustration from Mountain Craft by Geoffrey Winthrop Young. New York, 1920.

Illustration of boot nails from Mountaineering Art by Harold Raeburn, 1920.

In 1920 a pair of climbing boots went for about £3.00 - the equivalent of $28.63 in 2017 US dollars. However, climbers got much less for their money than we get out of our modern boots.

Original hobnails, stored in a reused box

“There is no use asking for “waterproof” boots; you will not get them.”

In addition to being heavy, the boots were not waterproof. Mountaineers had to apply castor oil, collan or melted Vaseline to the boots before each trip. This kept the boots flexible and also kept at least some water out. Animal fats were also an option, but they had a strong, unpleasant smell and would decompose, causing the leather and stitching of the boots to rot as well.

Hobnail boots

in action on Mumm Peak, Canada. 1915

Photo from our Andrew James Gilmour collection.

Boots with linings were not recommended for mountaineering, as the linings were usually made of wool and other natural fibers which were slow to dry when inside a boot. Wet boot linings, either due to water or snow leakage or human sweat, were a major cause of frostbite resulting in the loss of toes.

When not in use, the boots needed to be stuffed with dry paper, hay, straw or oats which were changed at intervals to ensure that all moisture was absorbed. If they weren't stuffed in this manner on an expedition, they were in danger of freezing and twisting out of shape.

A pair of worn hobnail boots set to dry over a fan in about 1920. This luxurious set-up was possible because the mountaineer was staying in a Swiss hotel.

Photo from our Andrew James Gilmour collection.

“Look with suspicion upon the climber who says he wears the same pair of boots without re-soling for three or four years. It will probably be found that his climbing is not of much account, or he is wearing boots which have badly worn and blunted nails, with worn-out and nail-sick soles, a worse climbing crime if he proposes to join your party, than if he were to wander up the Weisshorn alone.”

Crampons

Today crampons are made of stainless steel and weigh about 1 to 2 lbs. They can be bolted or strapped to the boot. In the early 20th century, crampons were made of steel or iron. They were strapped to the boot with hemp or leather straps passed through metal loops attached to the frames. Surprisingly, they didn't weigh too much more in the 1920s than they do today.

They could be bought in a variety of configurations, including models ranging from four to ten spikes. Mountaineers who recommended their use wrote that good crampons should have no fewer than eight spikes which should not be riveted to the frame. The crampons also should not be welded anywhere and the iron variety were likely to break if any real work were required of them.

A steel crampon with eight spikes and hemp and leather straps - ideal!

From the American Alpine Club Library archives

Good footwear is still one of the most important aspects of any trip. We're extremely grateful boot technology has advanced so much.