In 1925 Albert H. MacCarthy had just led a successful first ascent of Mount Logan in Canada, composed of climbers from Canada, Britain and the United States. MacCarthy, an American and member of the American Alpine Club, wrote a number of reports and summaries of the expedition, including this list of Mountain “Dont’s.”

Denali - First ascent of the South Face via the West Rib 1959

It had all begun on an afternoon some nine months previous. Four of us were lying about relaxing after a particularly fine Teton climb when someone enthusiastically suggested, "Let’s climb the south face of McKinley next summer!” To attempt a new and difficult route on North America’s highest mountain seemed a most worthwhile enterprise; without further ado, we cemented the proposal with a great and ceremonious toast.

The Andrew J. Gilmour Collection

by Allison Albright

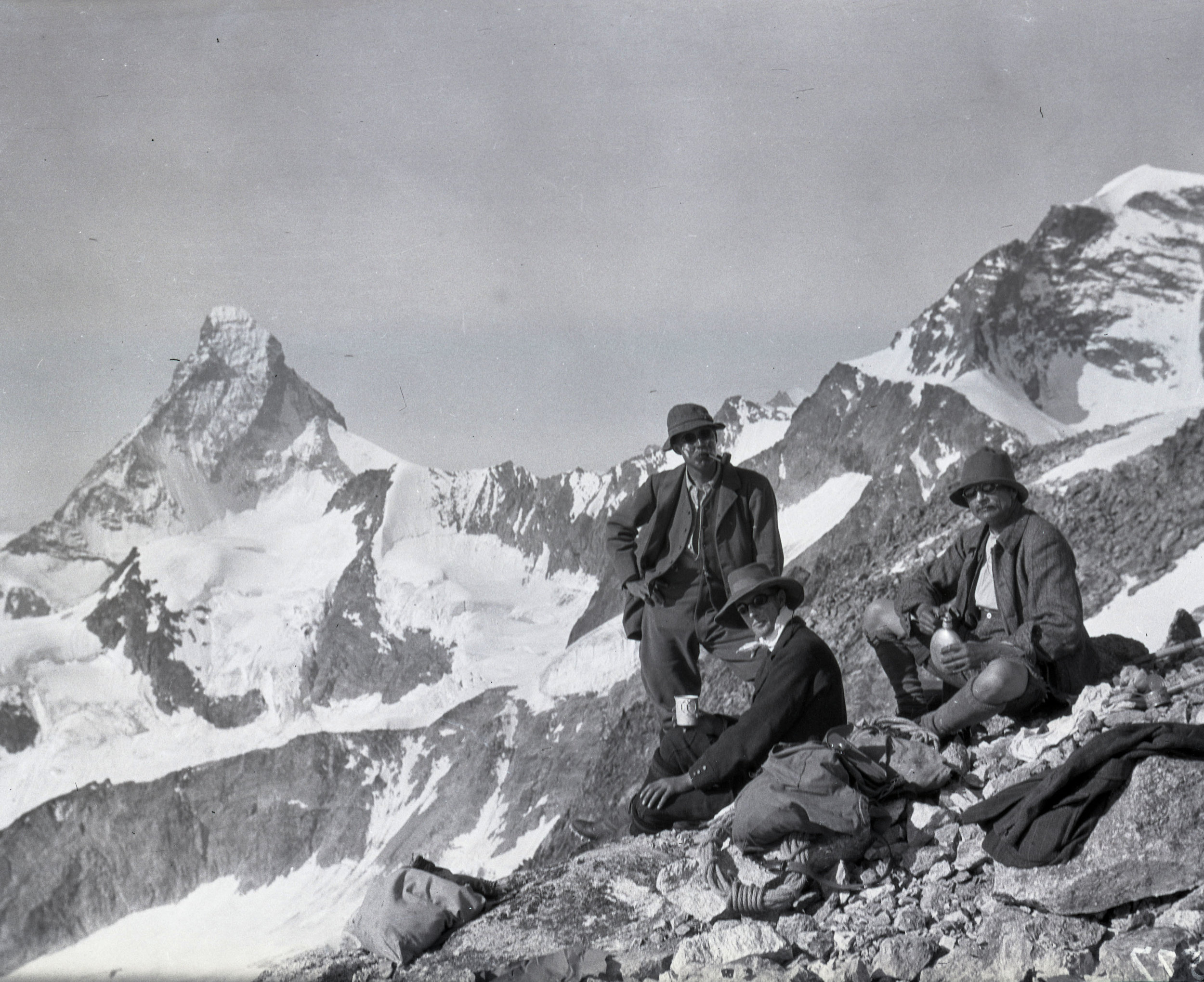

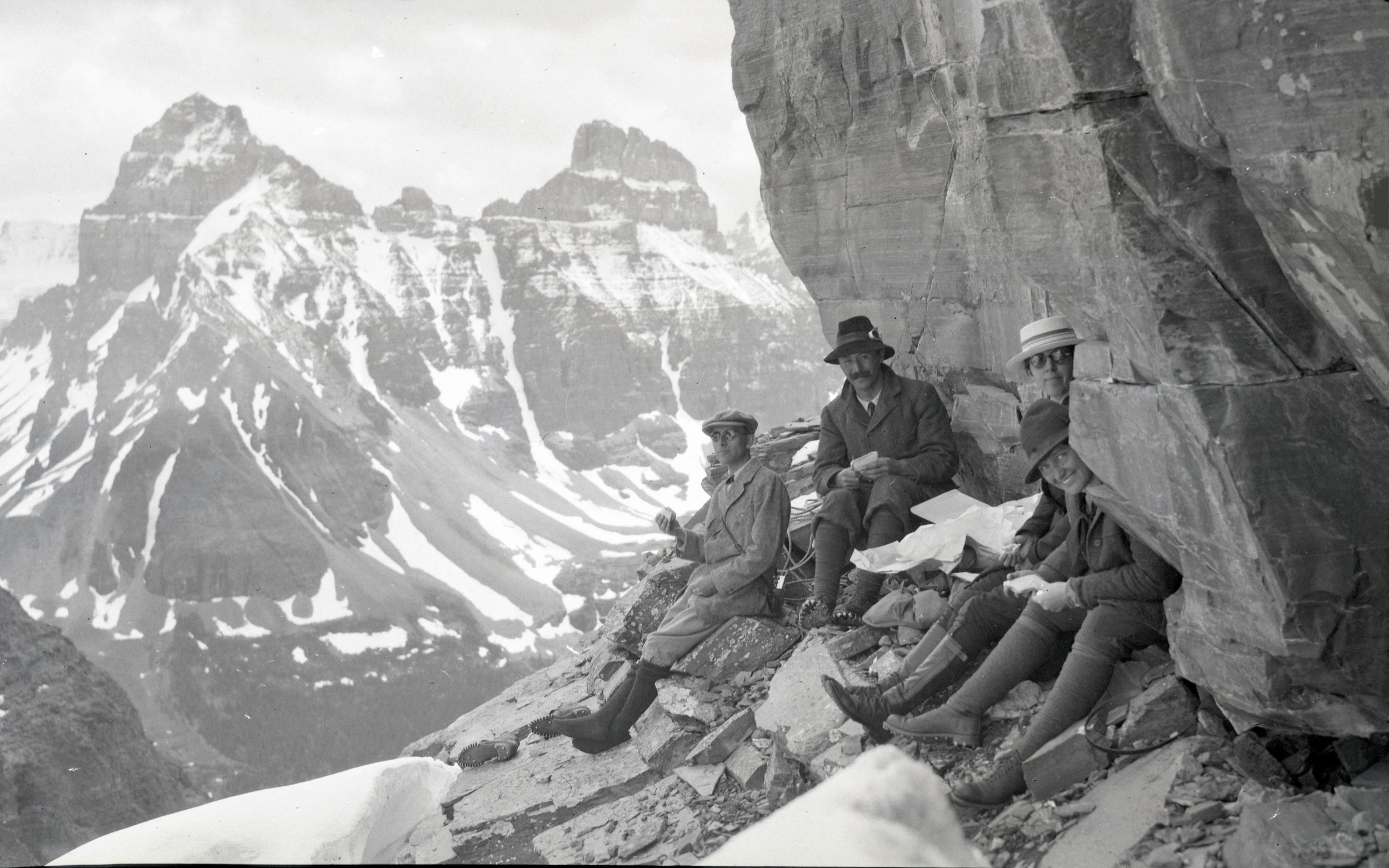

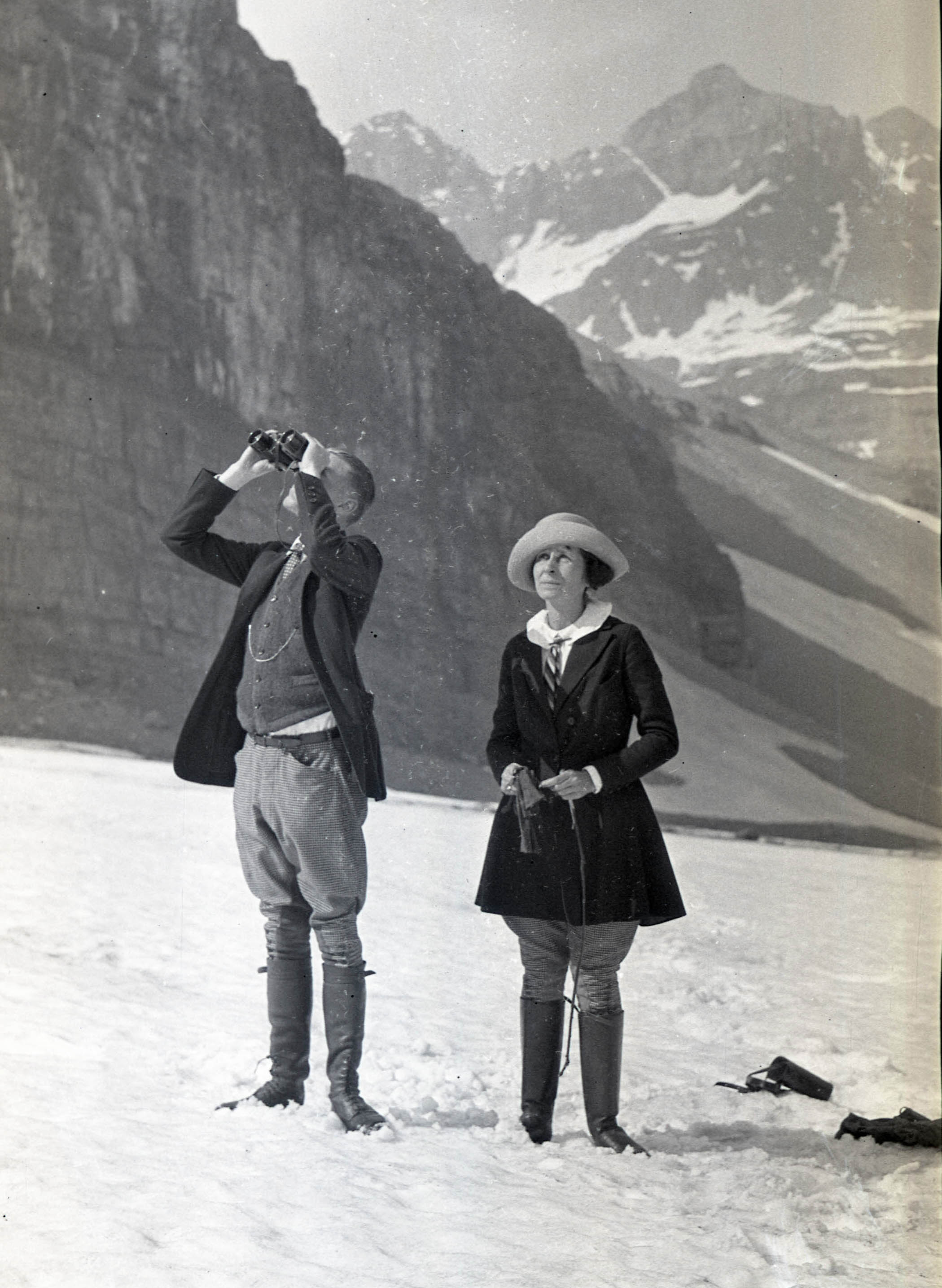

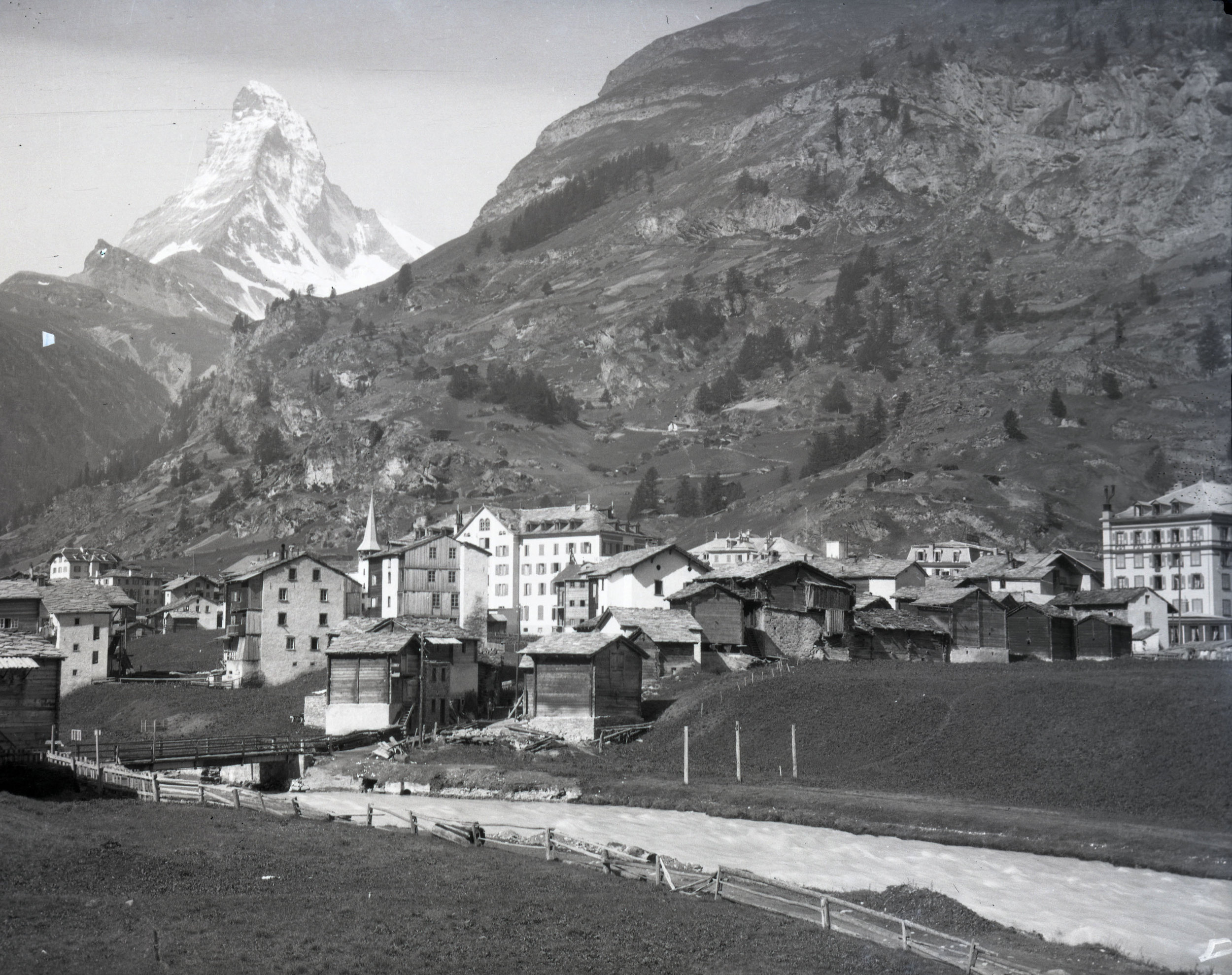

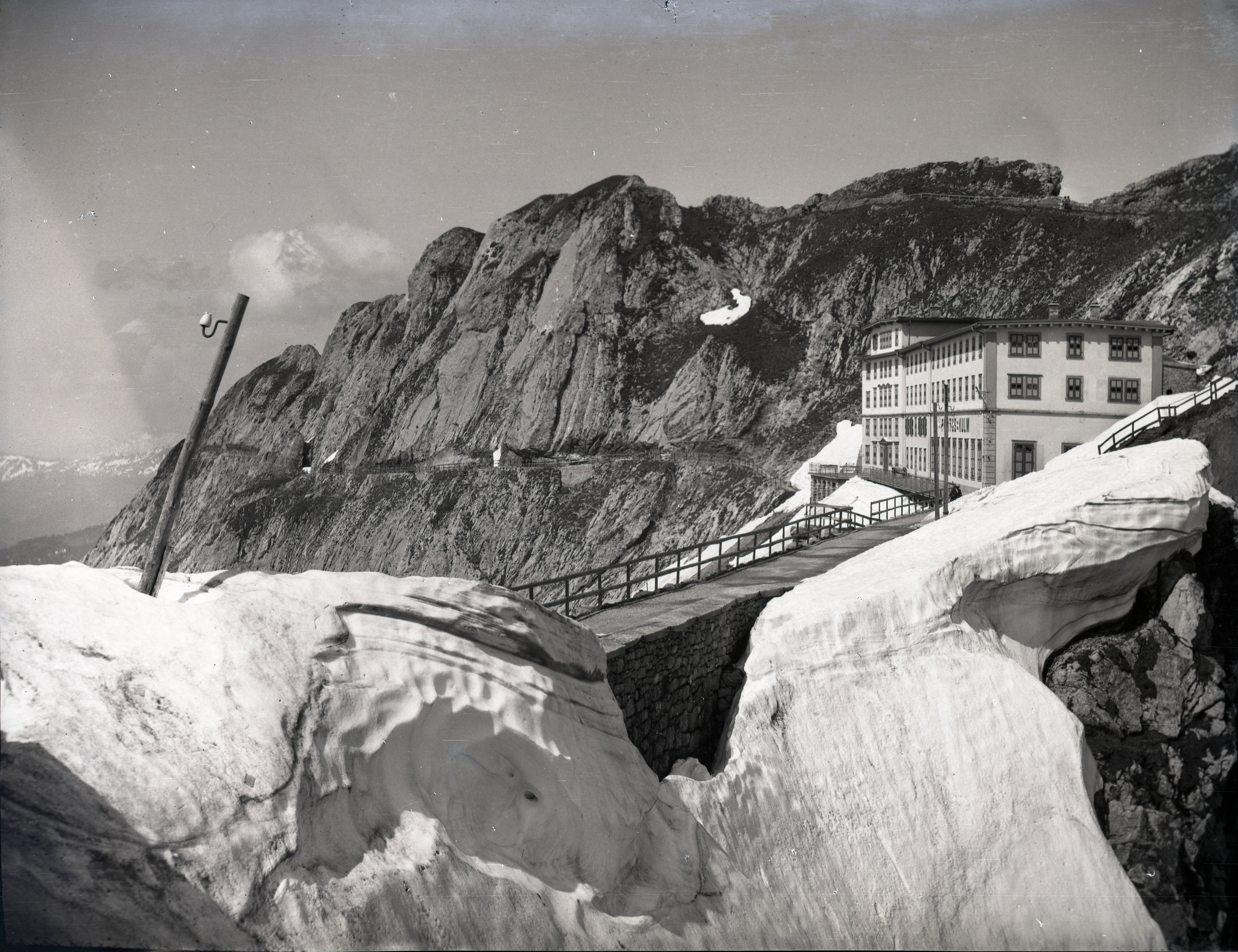

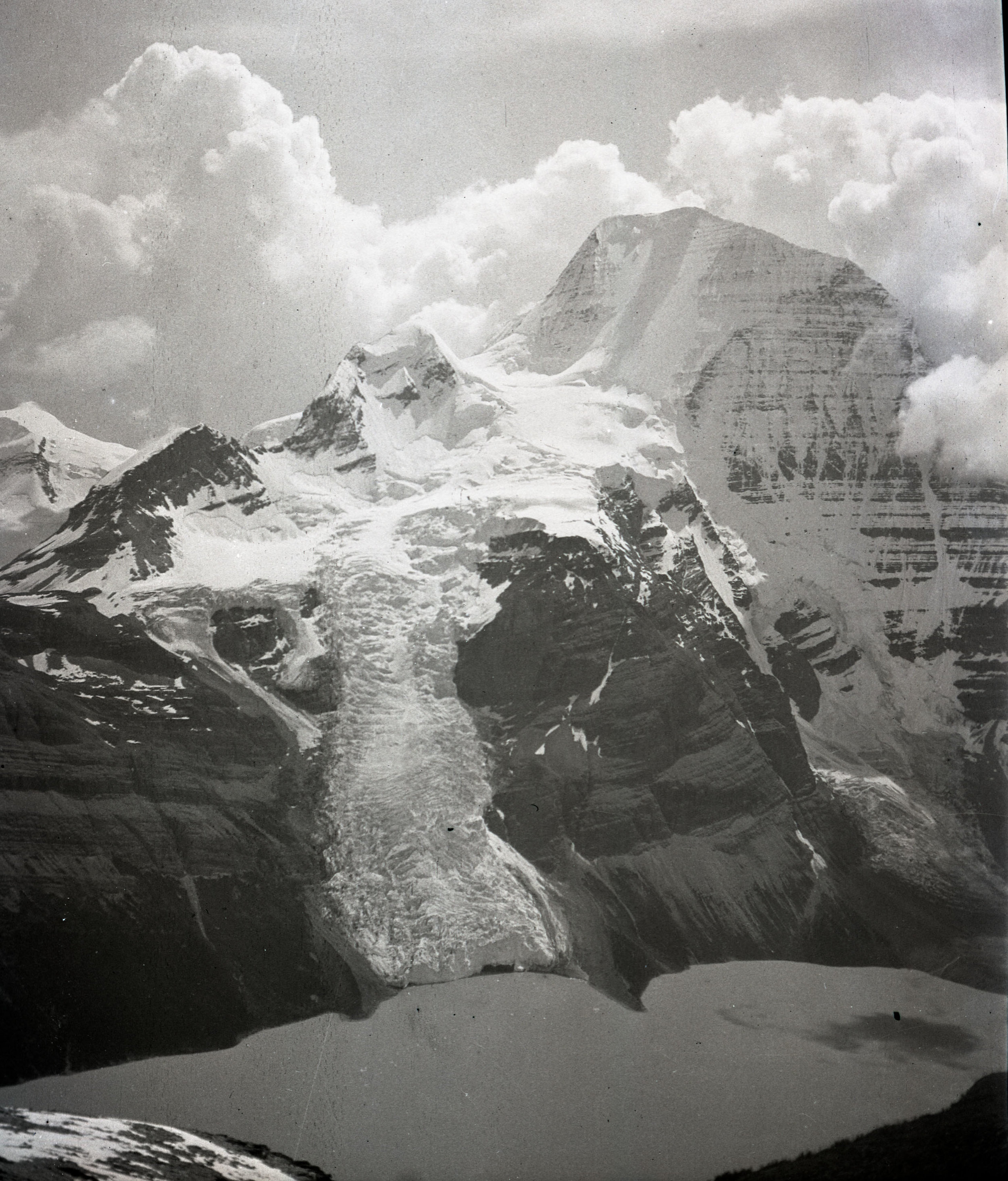

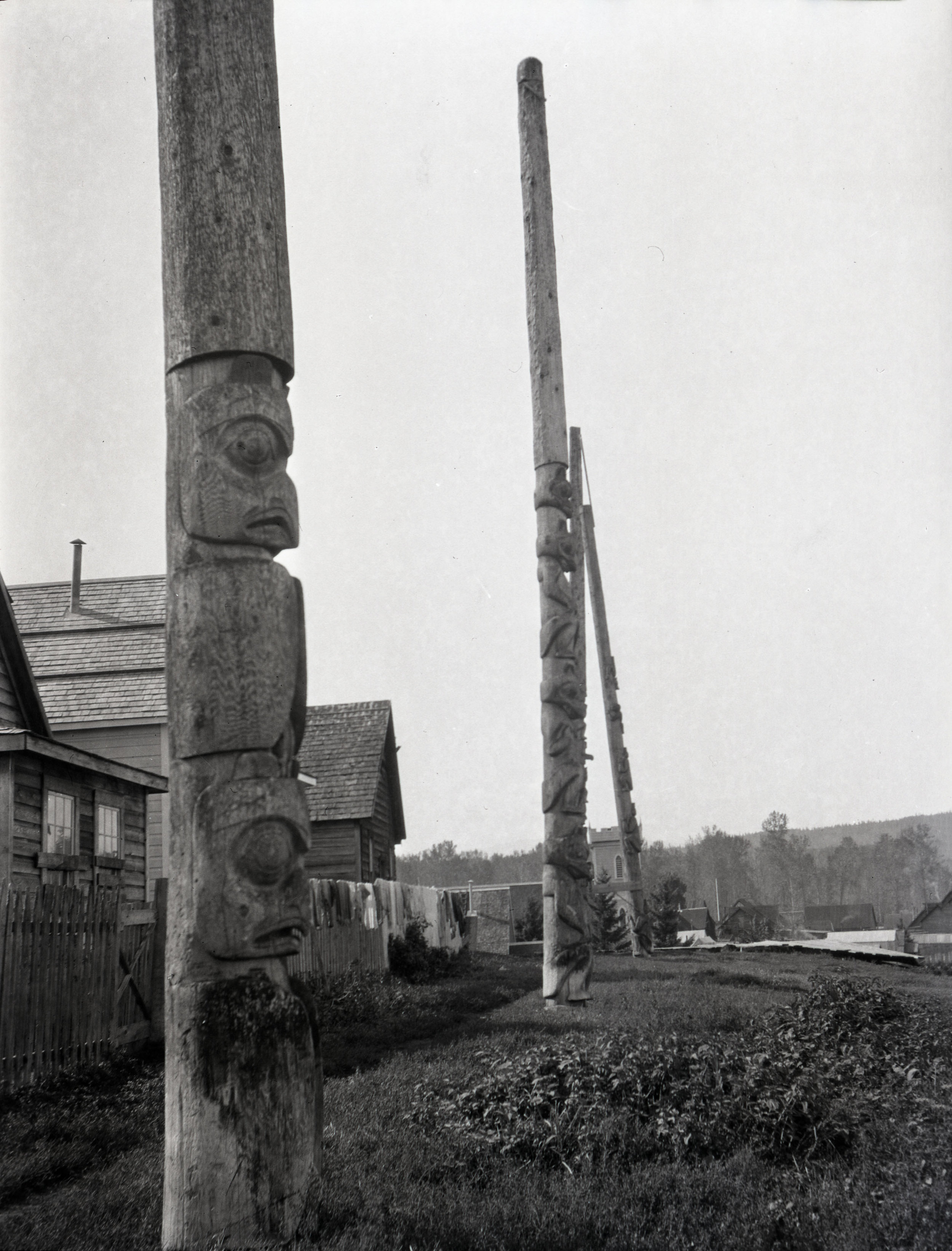

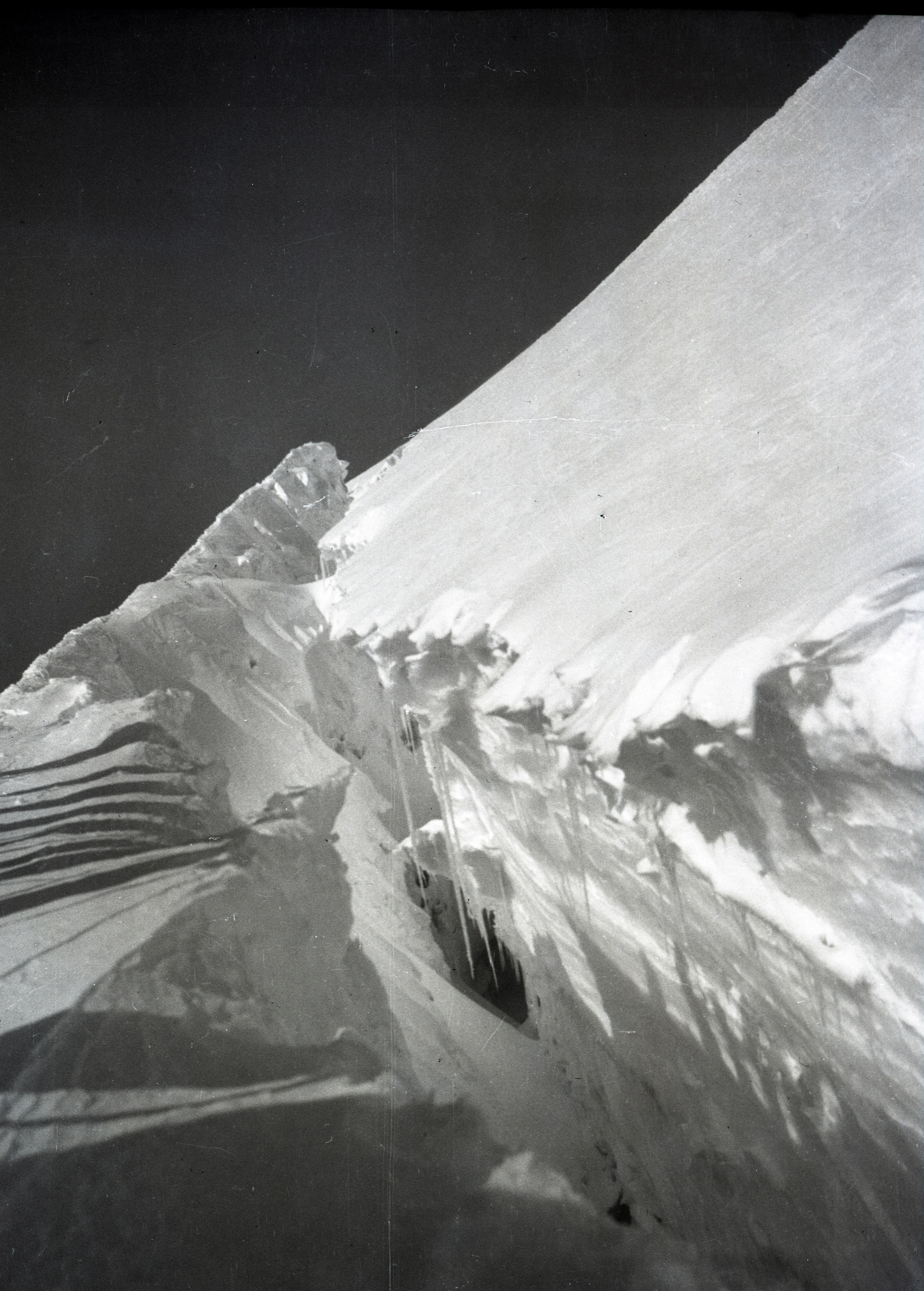

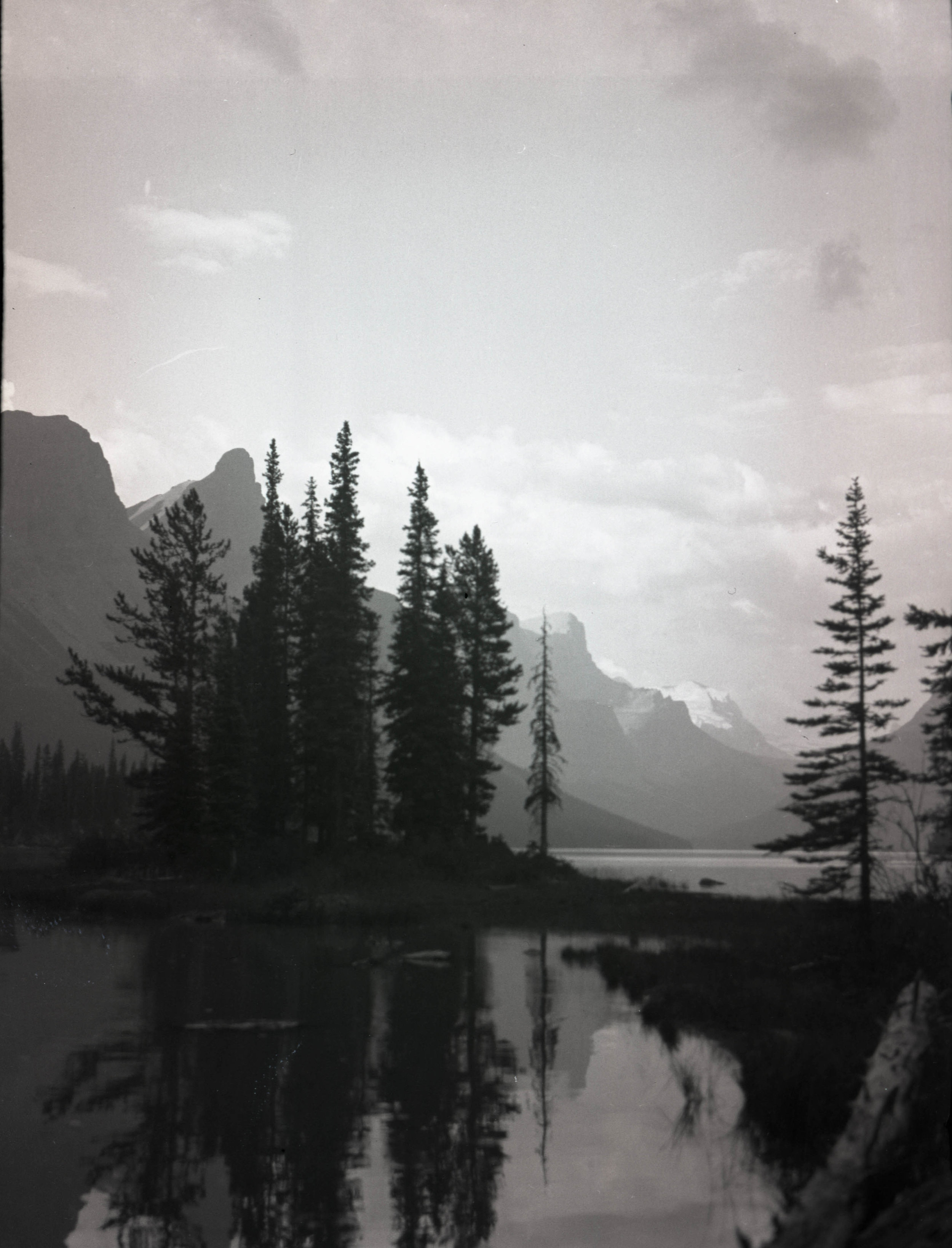

At the American Alpine Club Library, we’re very fortunate to have quite a few collections of photographs of climbing and mountaineering from the early 20th century. One of these, a collection of roughly 3000 photographic negatives dating from 1900 to about 1930, has been digitized in its entirety and made available to everyone.

It’s a great feeling to complete a project.

We’re excited to be able to increase access to this collection through digitization, which also reduces wear and tear on the original negatives and adds an additional layer of preservation.

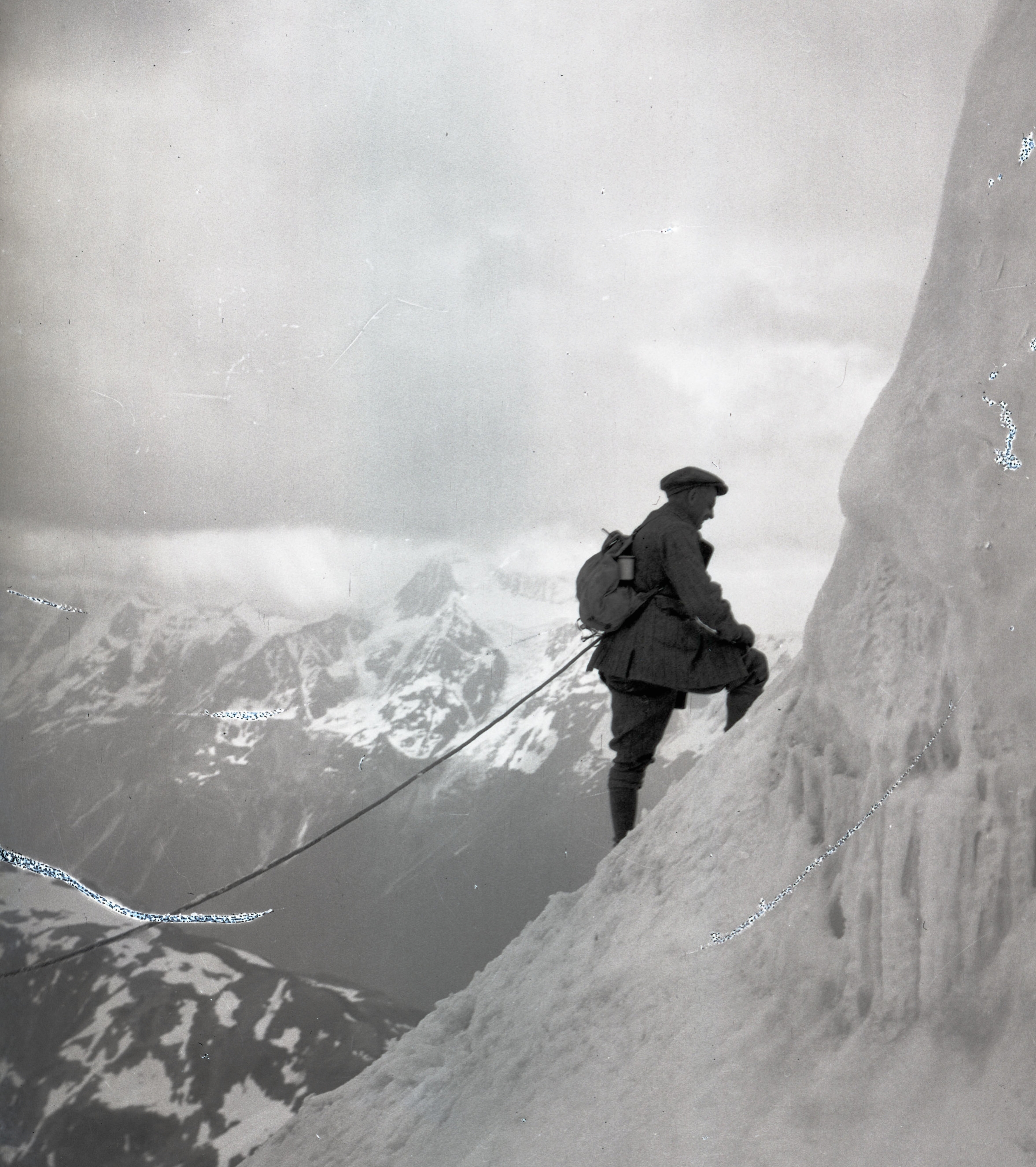

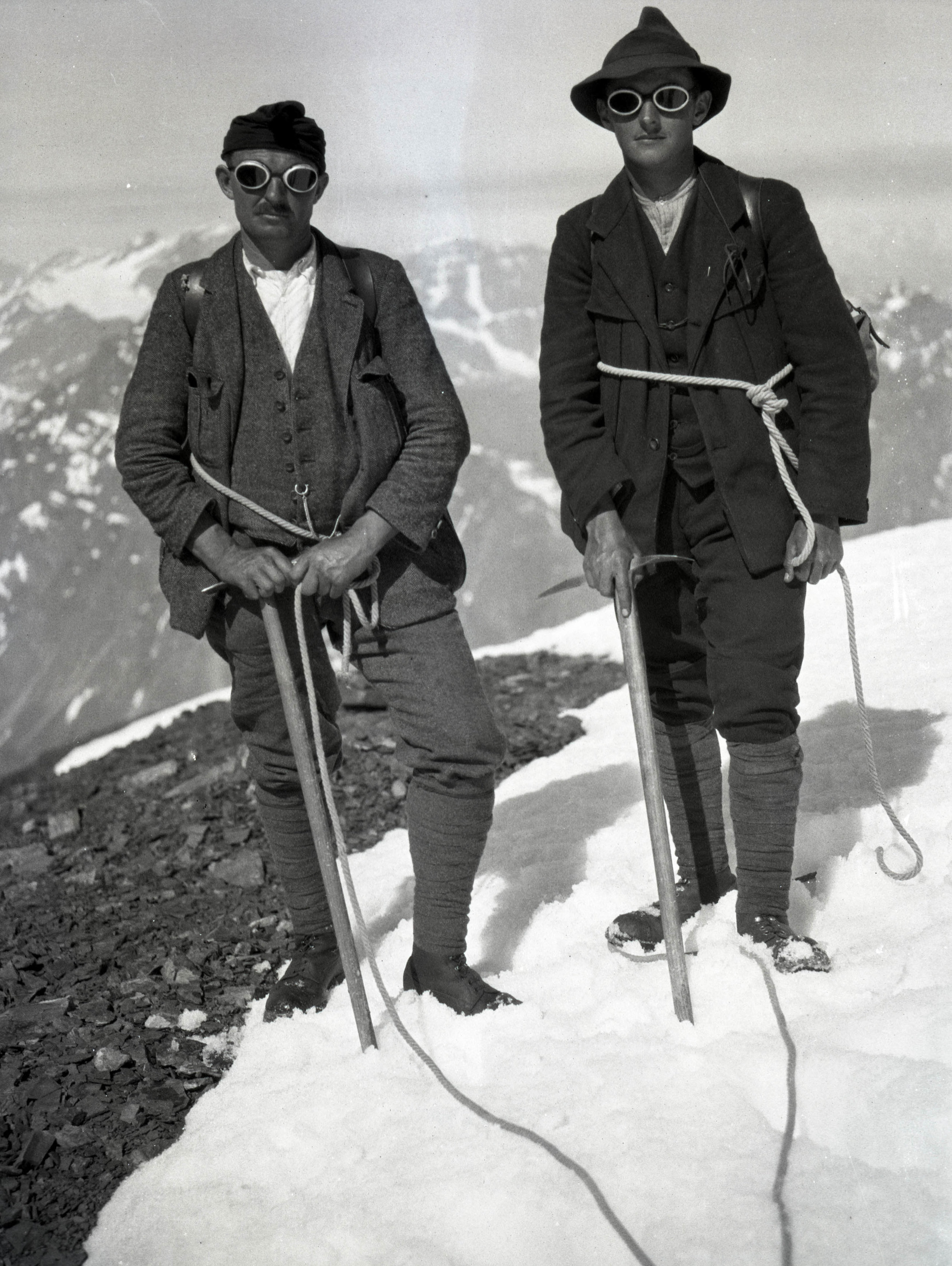

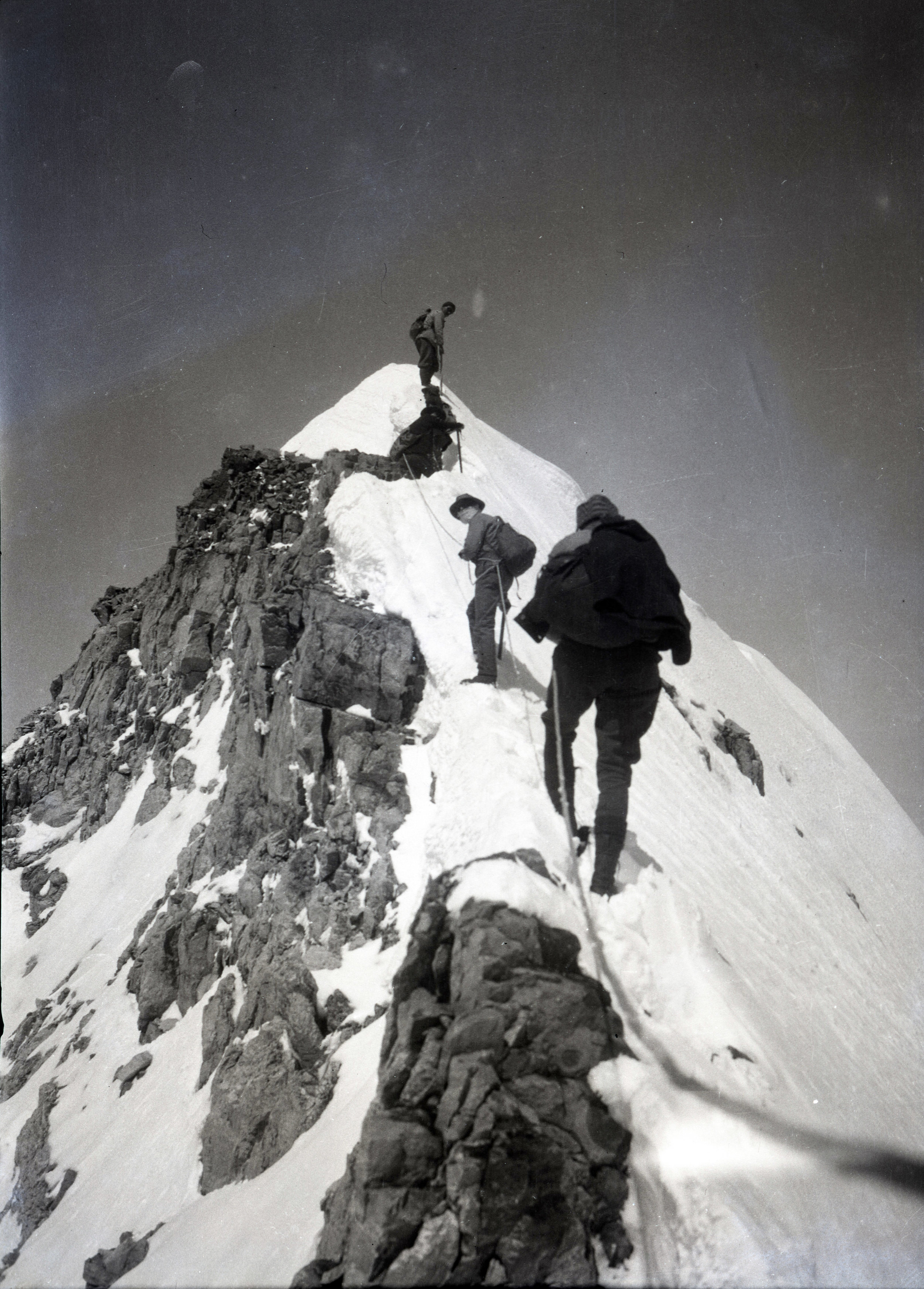

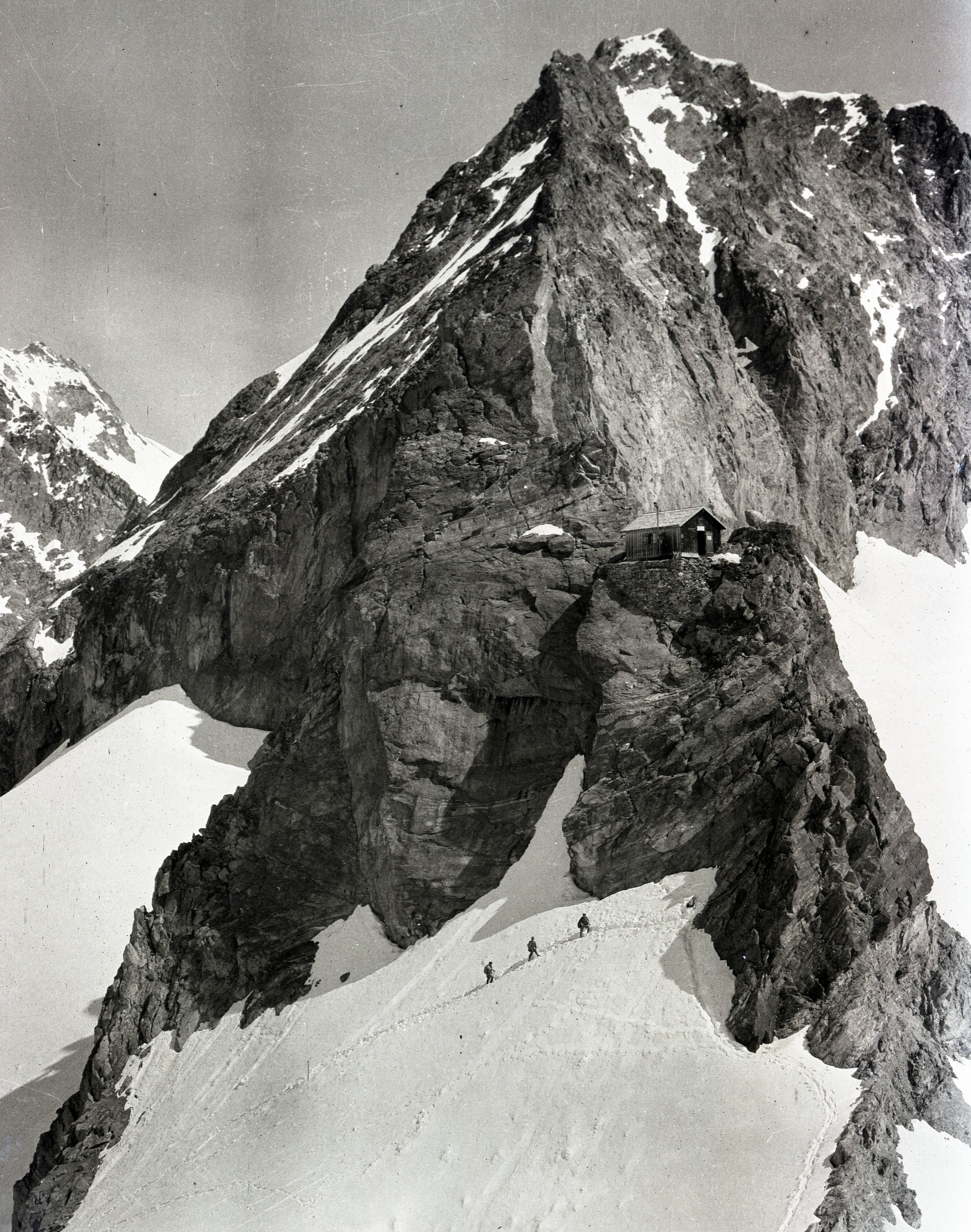

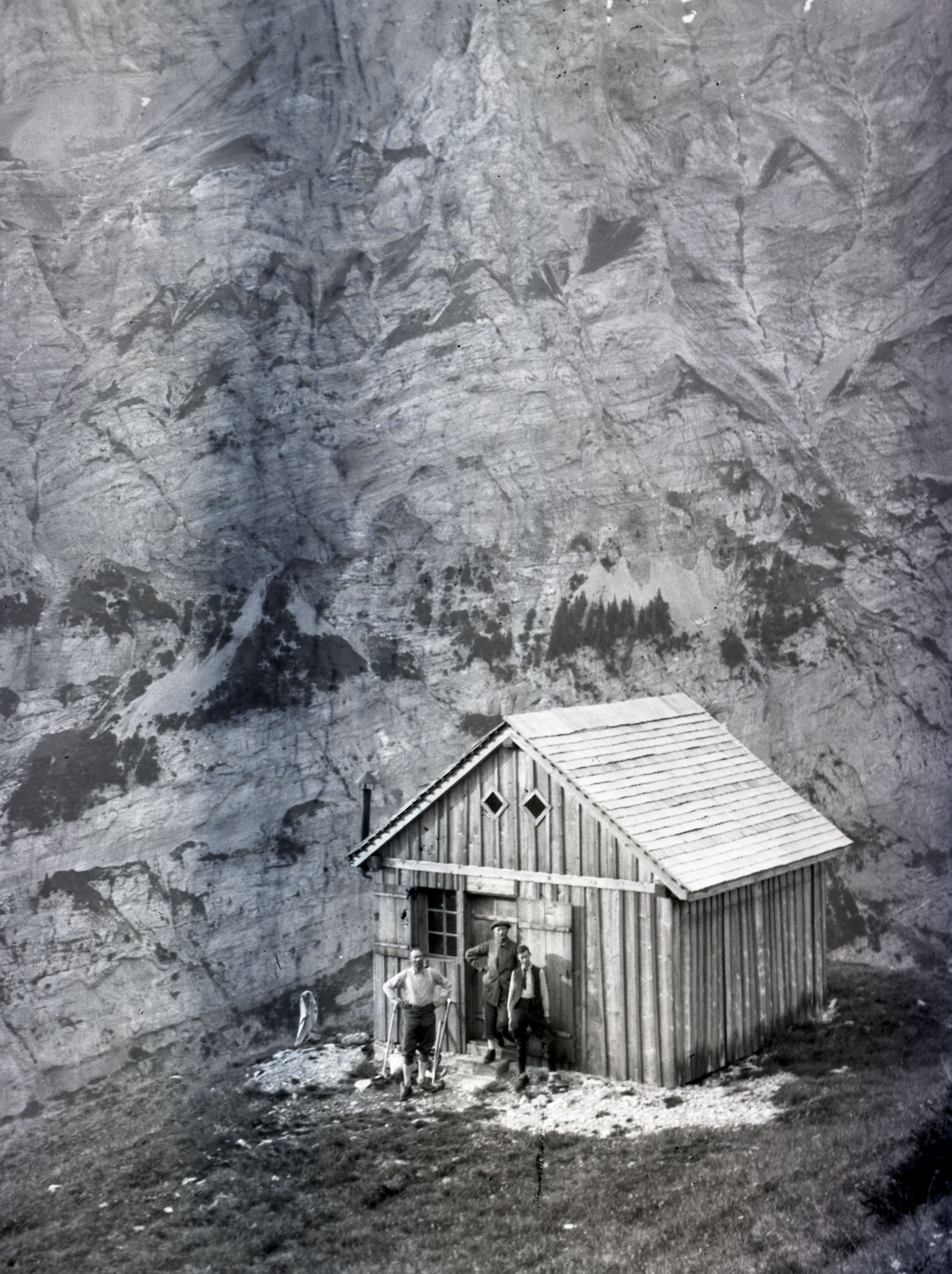

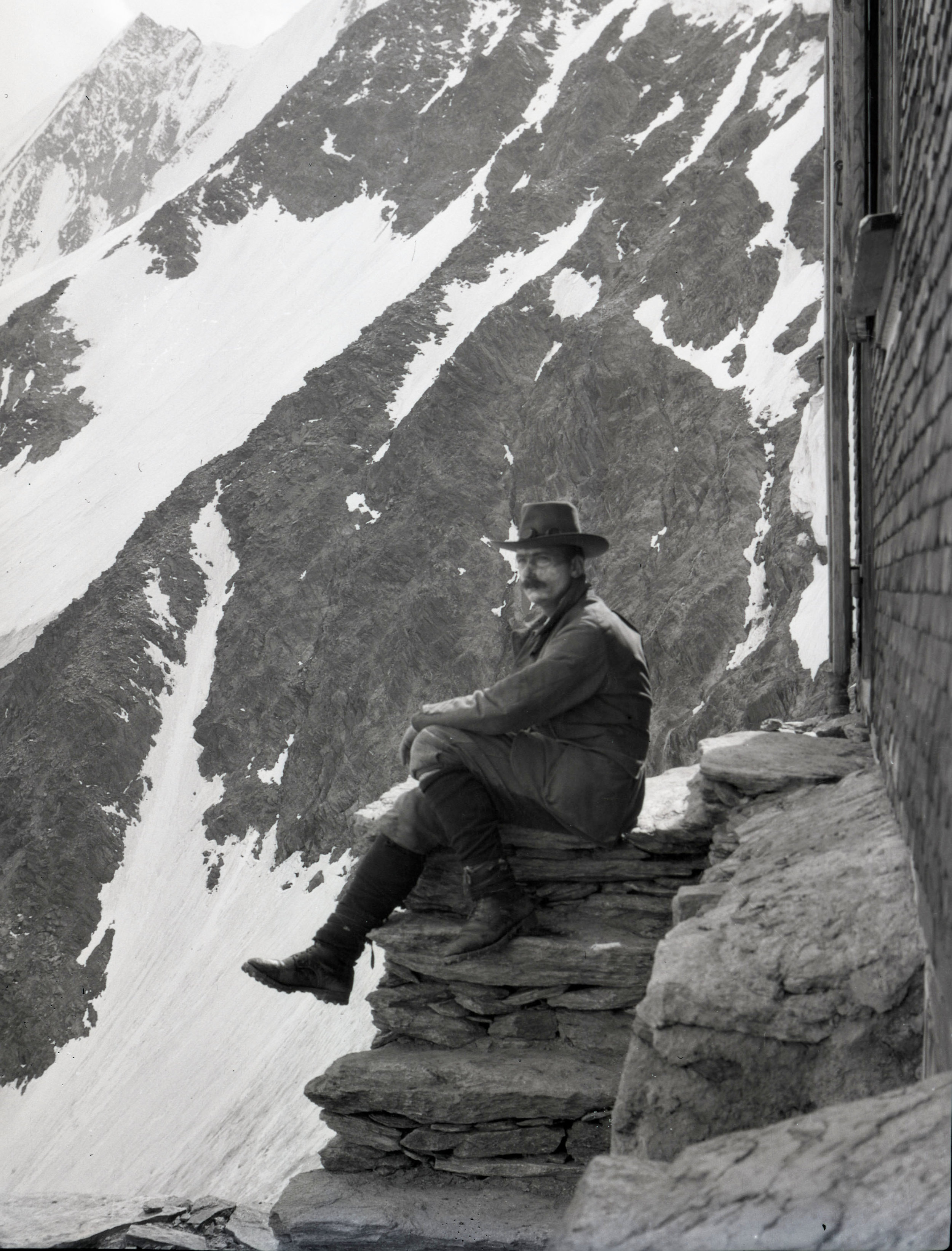

This collection of photos belonged to Andrew J. Gilmour, a dermatologist living and working in New York who was an avid climber and active member of the American Alpine Club during the 1920s and 1930s. He did a number of ascents in the Alps, the Canadian Rockies, the Cascades and the Western U.S., as well as Wales and the Lake District in the UK. His photos show us a lot about climbing at that time, the techniques, equipment, conditions and the people and places involved. It also provides us with a glimpse of what the world was like about 100 years ago.

We’ve gathered some of our favorite images from this collection in the slideshows below. Enjoy!

To see more of these images, check out our Andrew J. Gilmour album on Flickr.

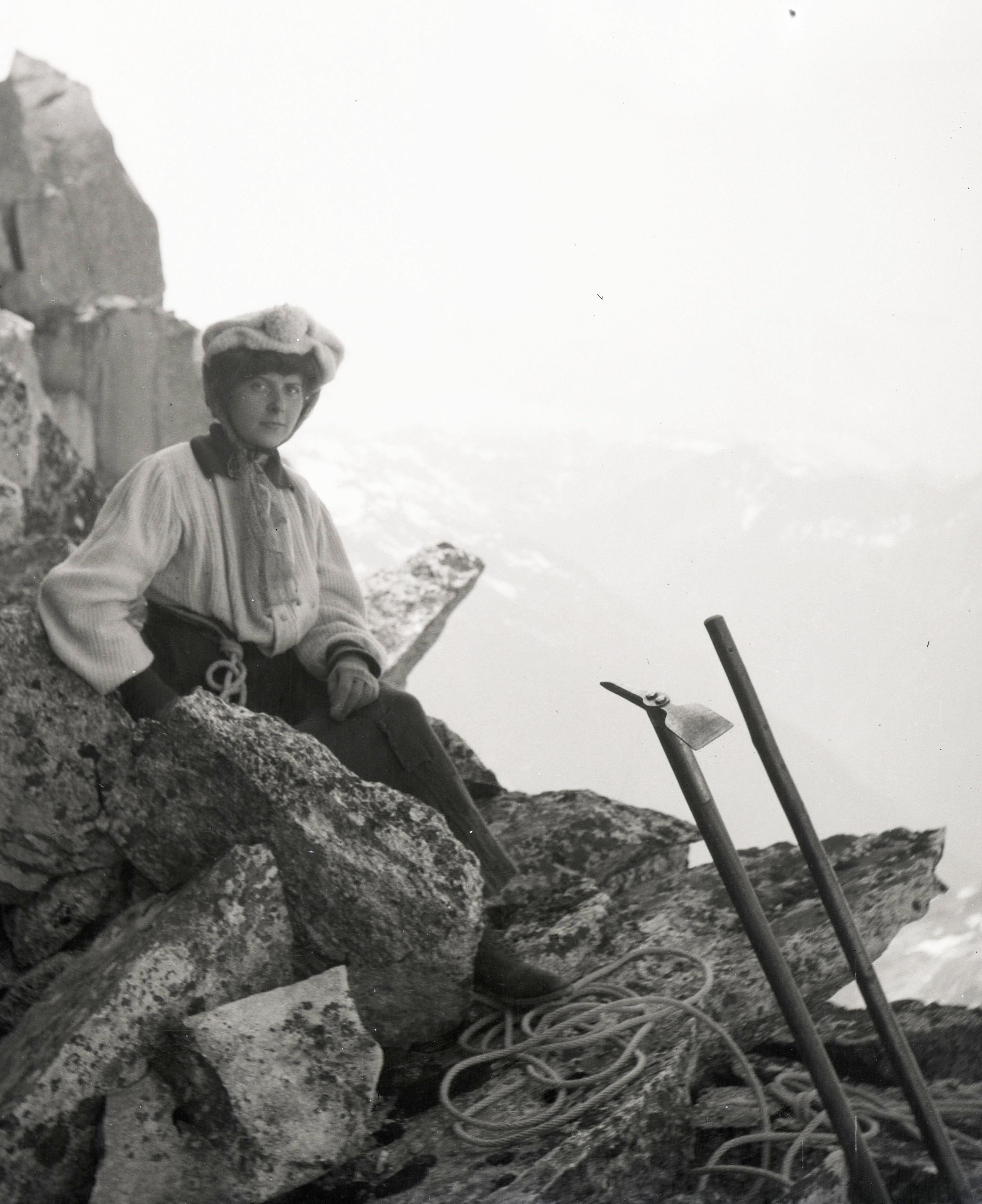

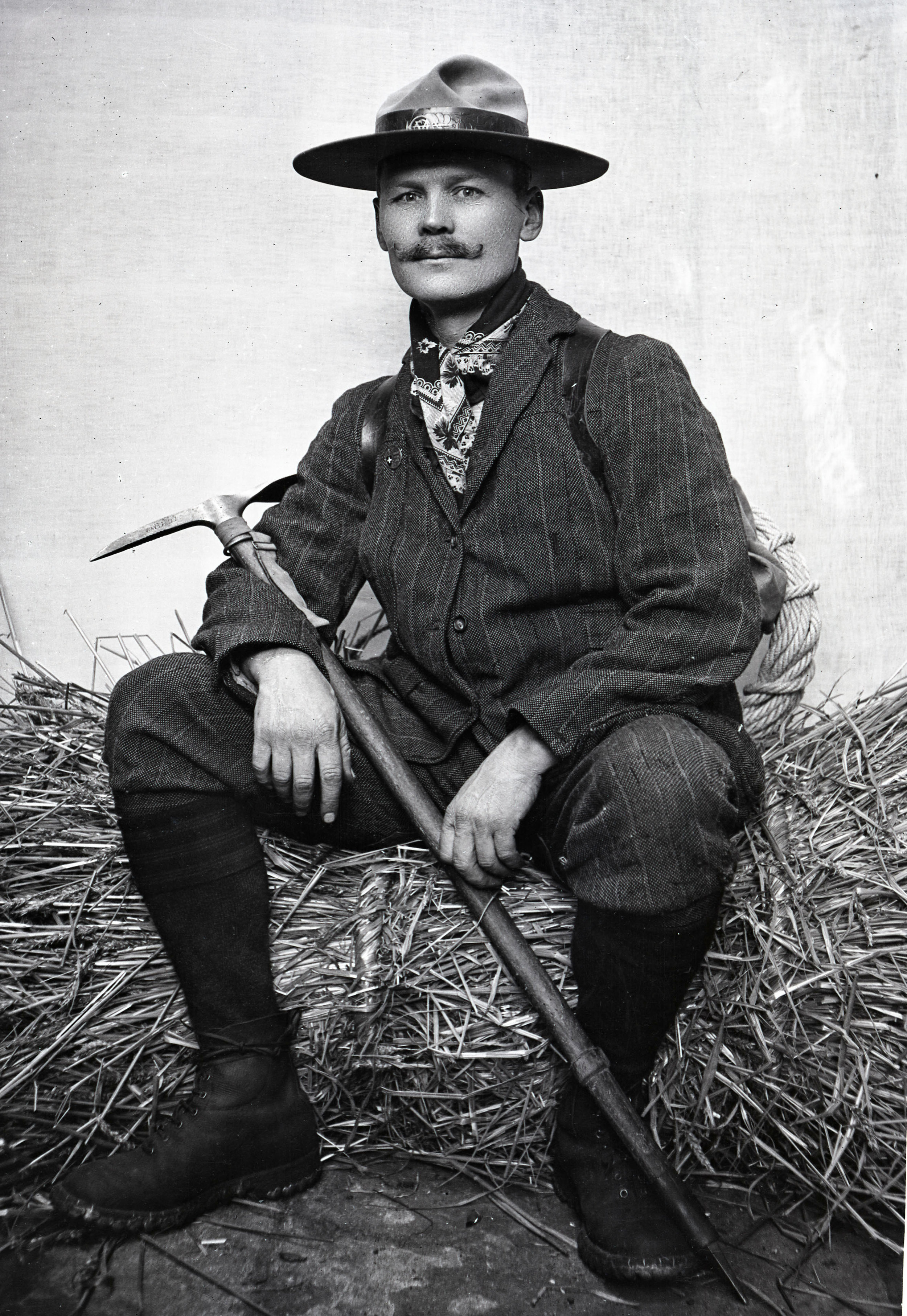

Climbing and Mountaineering

Photos of climbing parties and mountaineering expeditions from about 1910 to the mid 1930’s.

Equipment

Hobnail boots, hemp rope, canvas and silk tents and men’s and women’s climbing attire.

Summits

Men and women on top

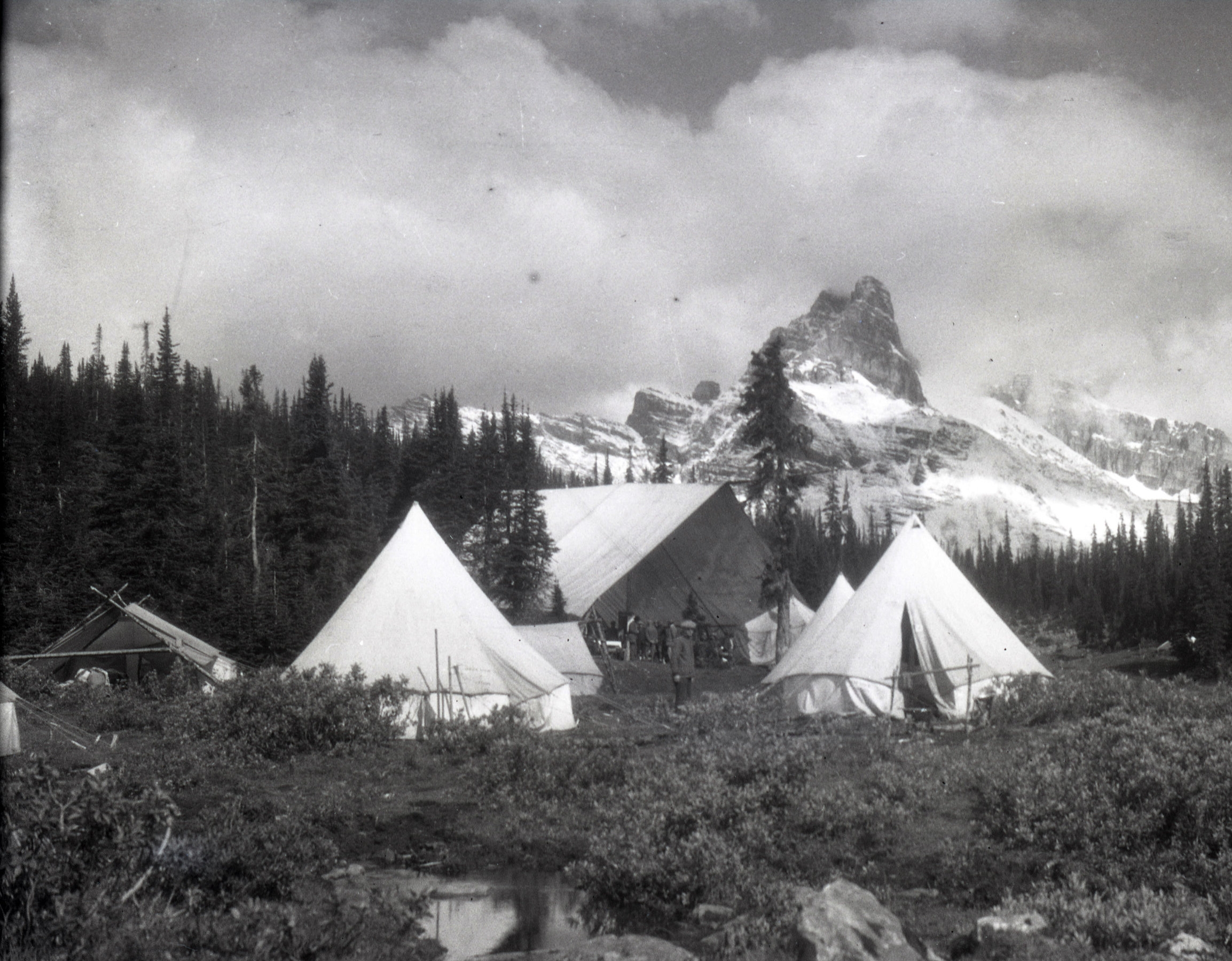

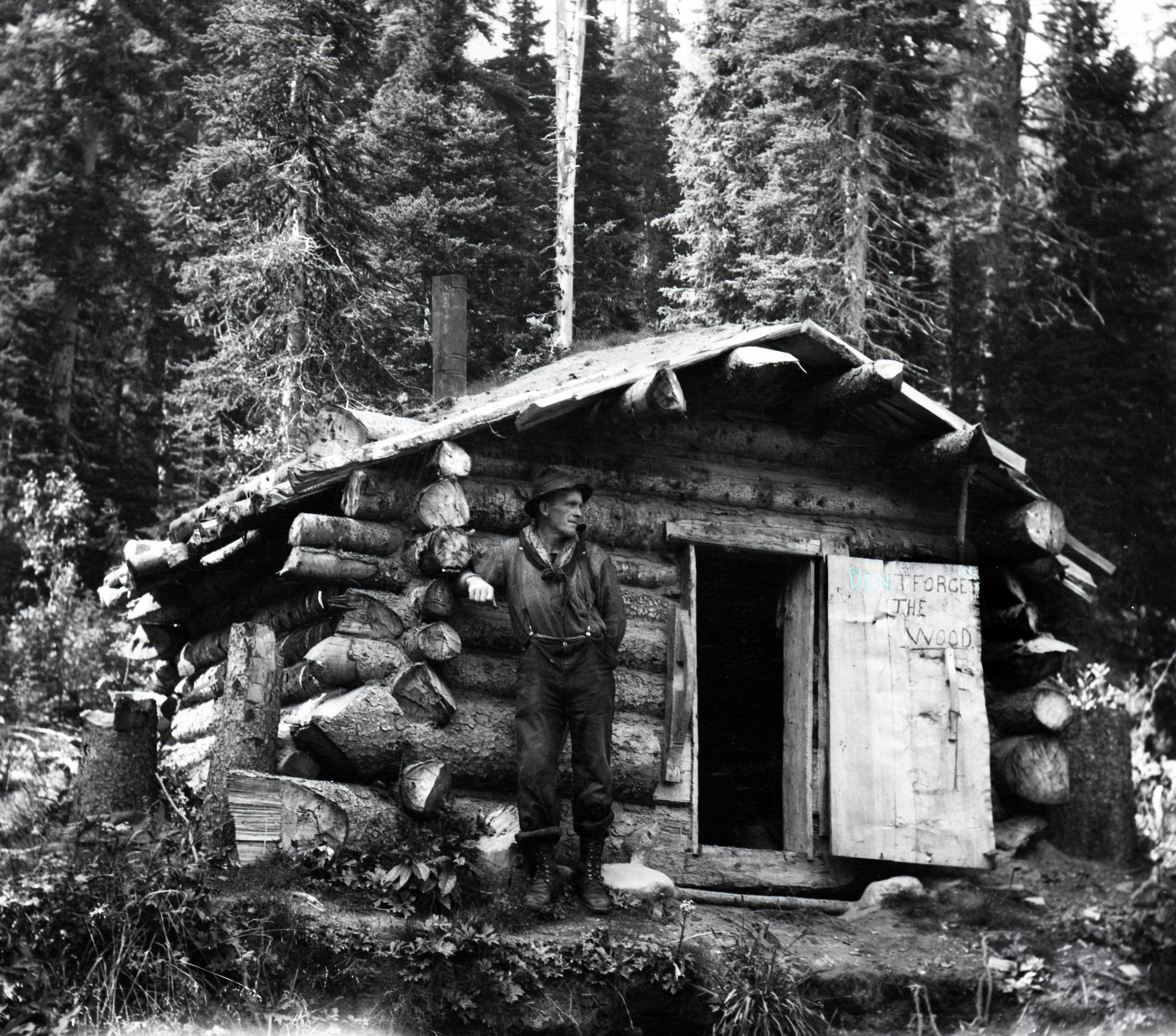

Camps and Huts

Huge camps for gatherings with the Alpine Club of Canada, tents and lean-tos in the woods, Swiss Alpine Club huts - many of which are still in use today.

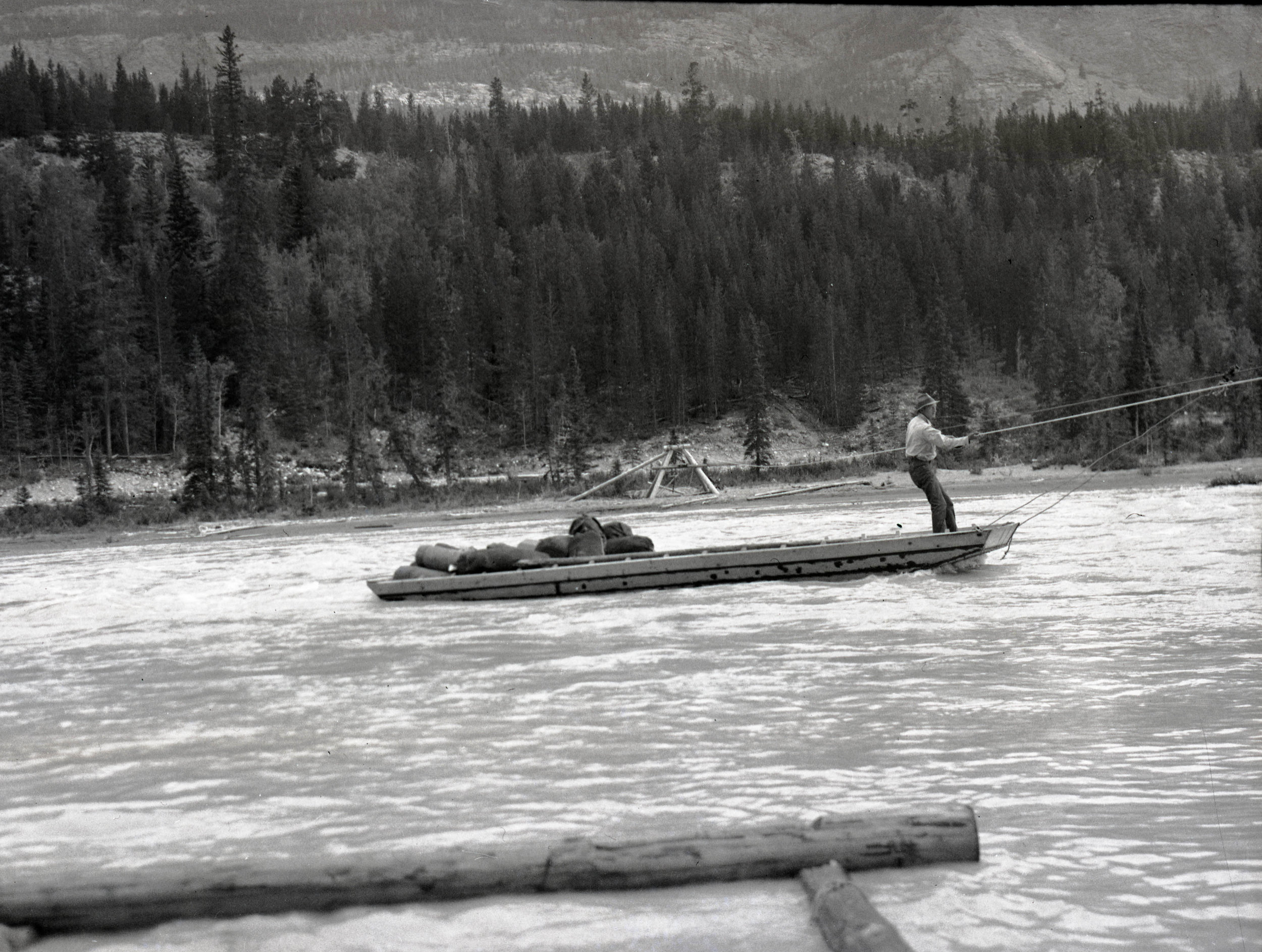

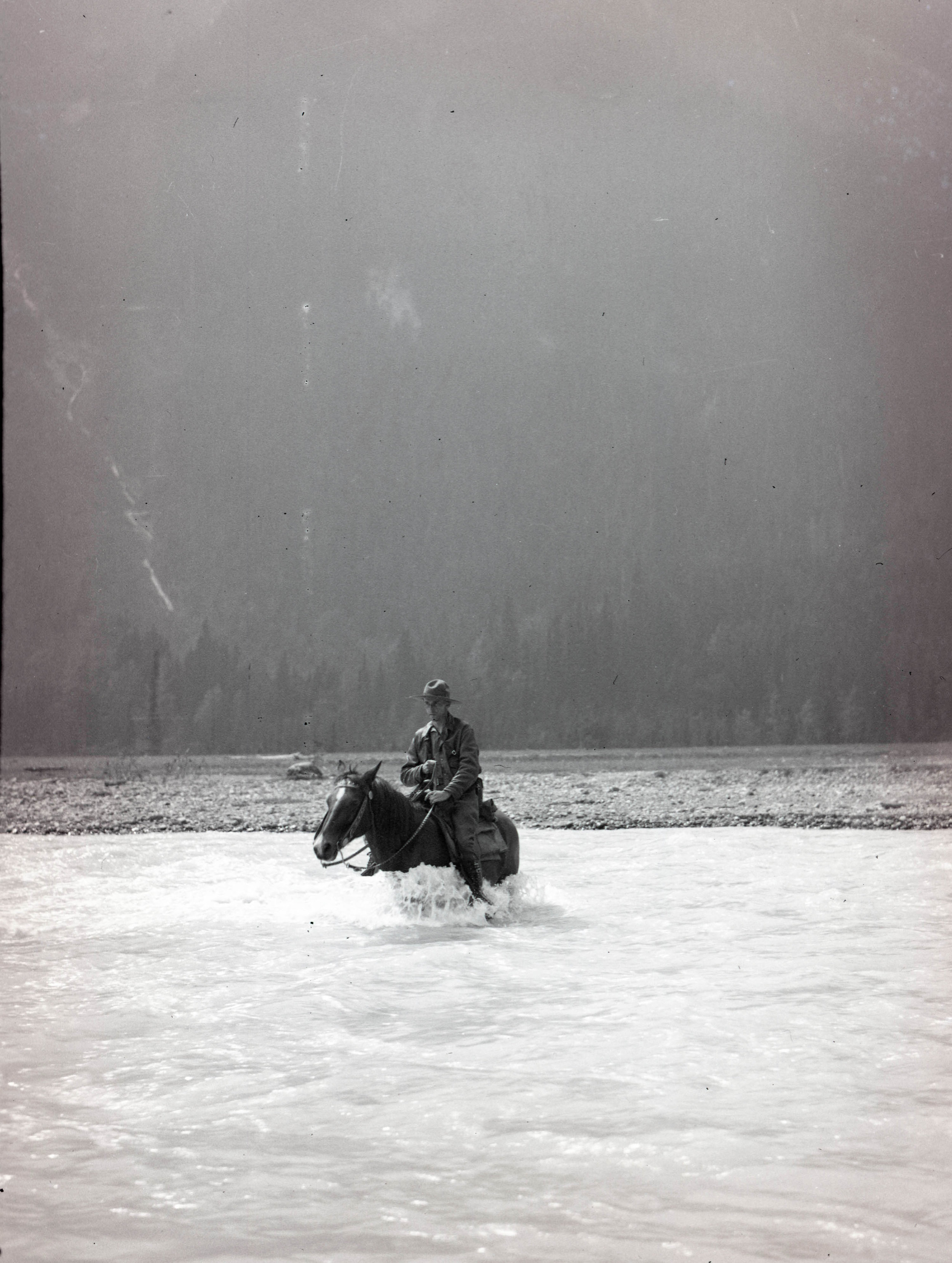

Travel

It was harder in those days to get to some of these remote locations. There were far fewer roads, almost no highways and air travel was still in its infancy. Trains, ships and horses were commonly used.

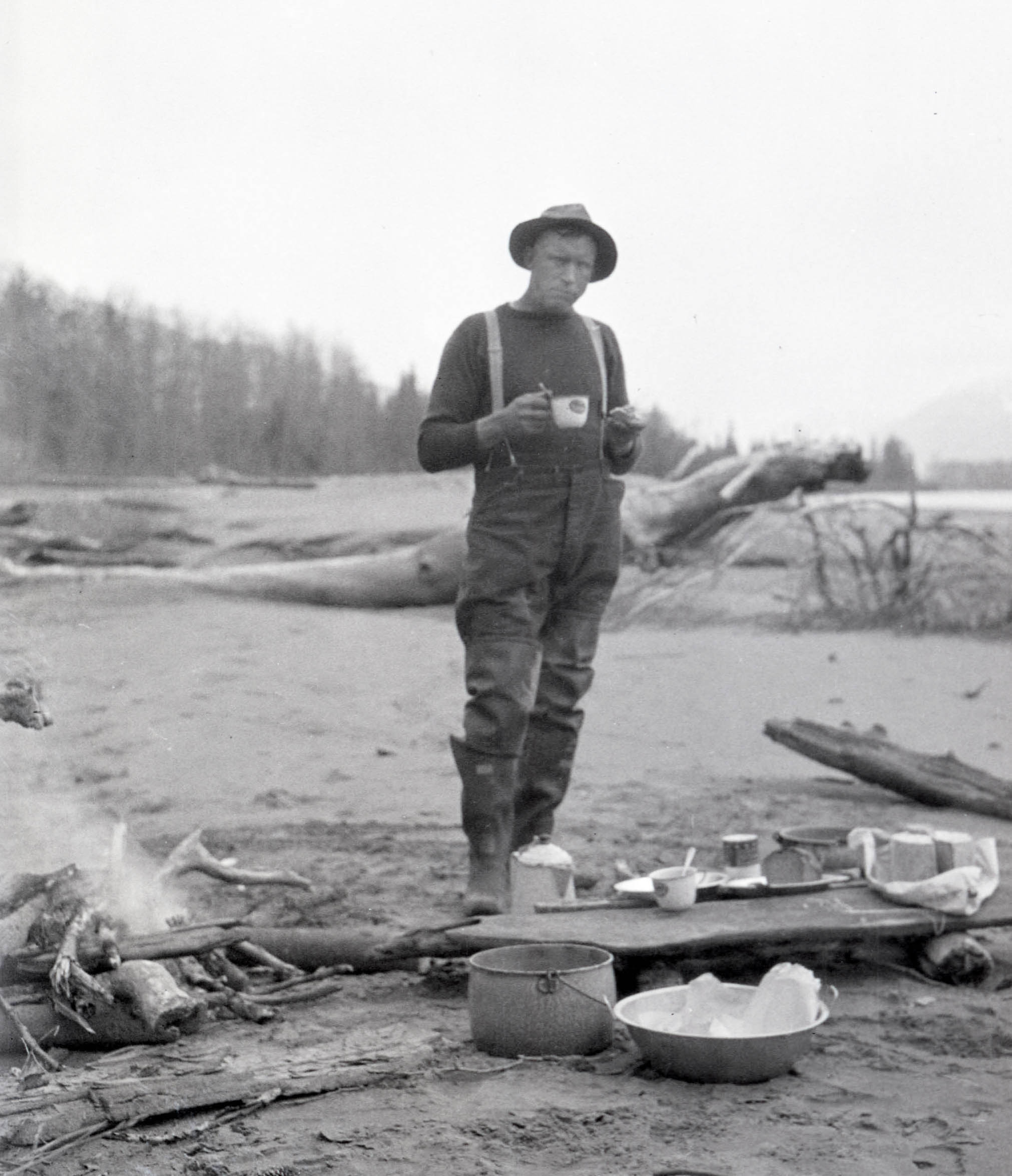

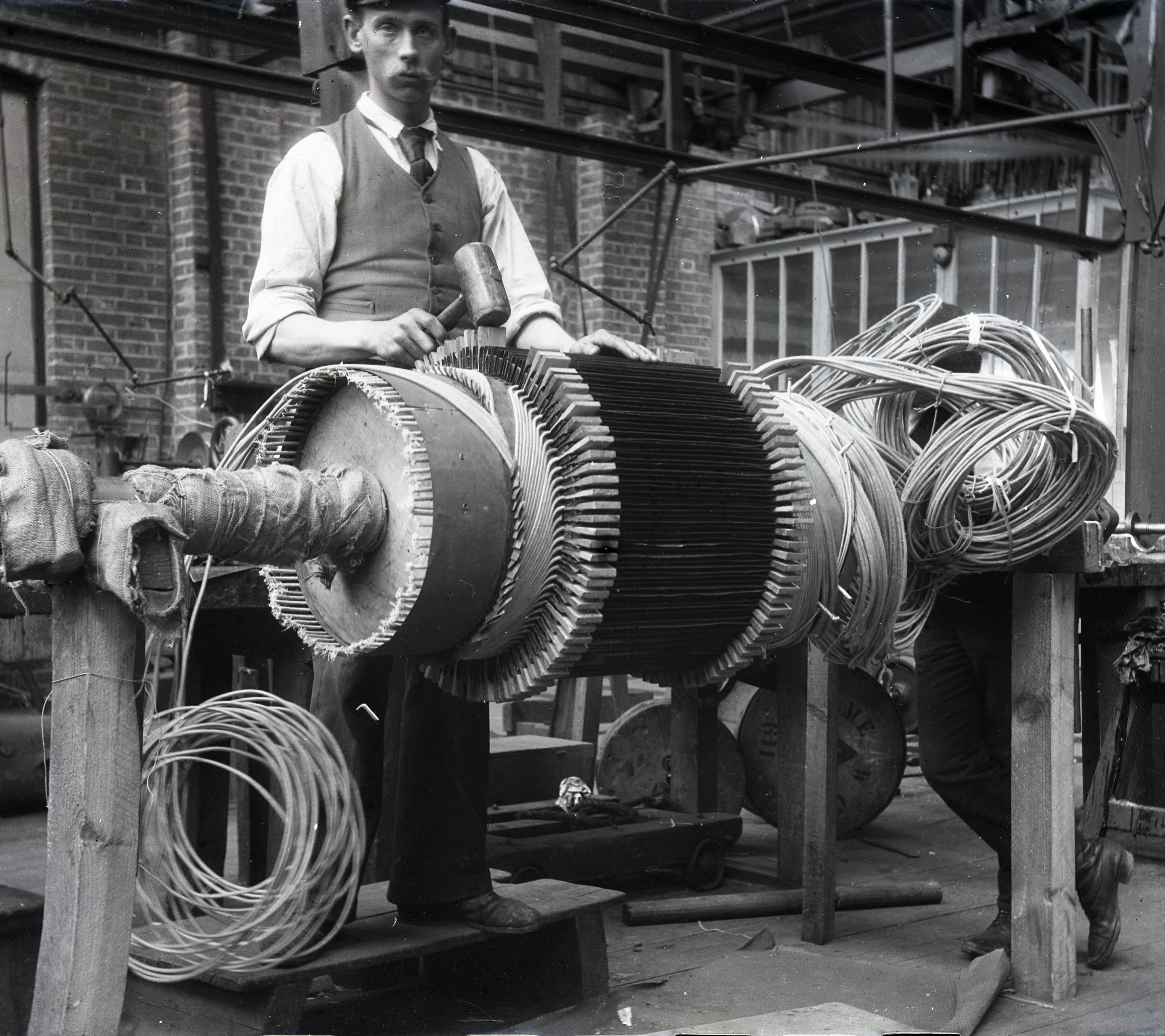

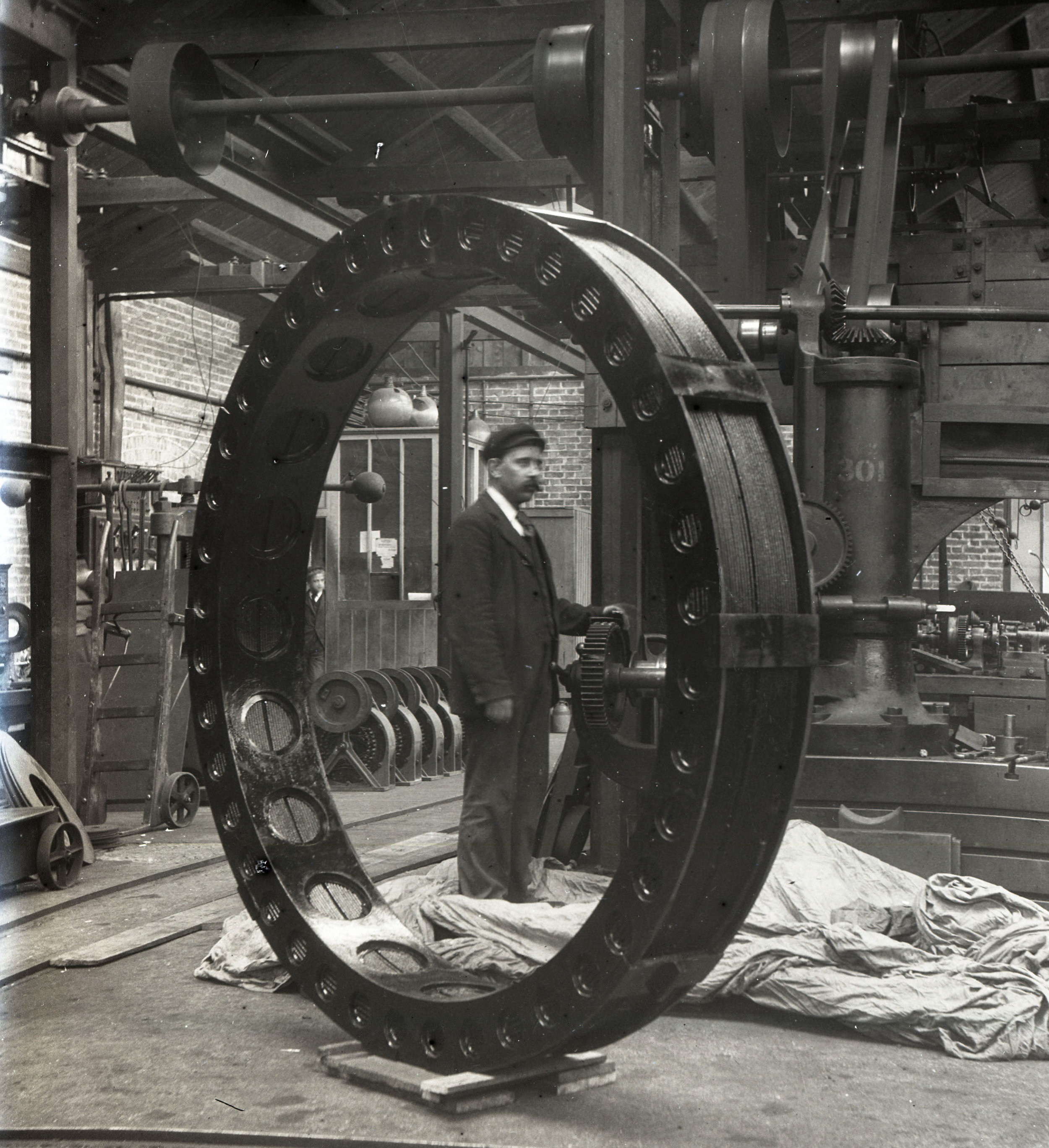

Life and Times

The world has changed a lot since 1900 - these photos illustrate just a few of the differences.

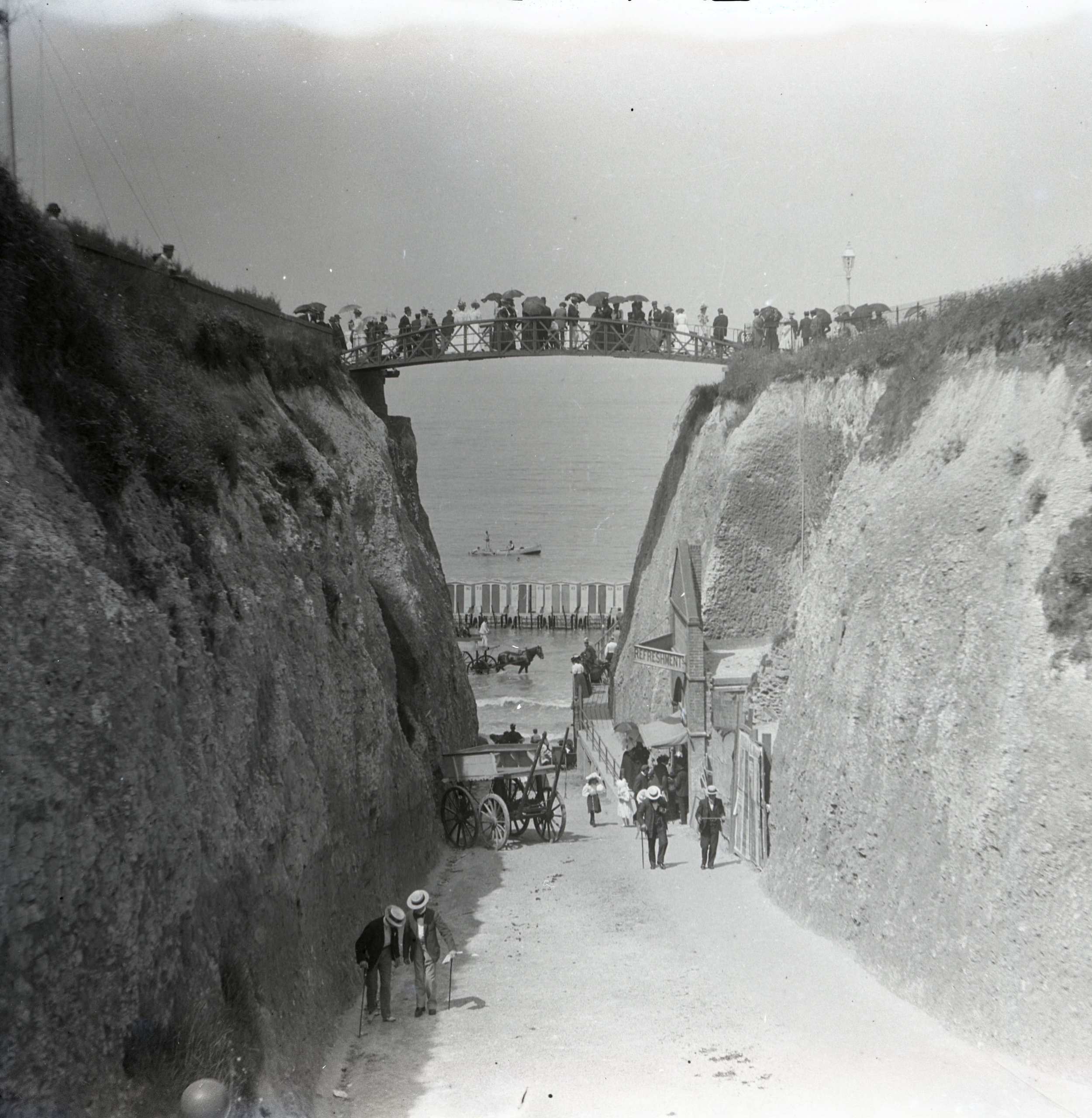

Places

Some gorgeous photos of some famous locations as they used to be.

Check out our Flickr account for more! Or, to view all the photos, head to our archival collections site and scroll down to Collection Tree.

Suggested reading:

For details of mountaineering and climbing in the first decades of the 20th century, check out the handbook Mountain Craft by Geoffrey Winthrop Young.

For more about some of the places depicted in these photos:

Mount Rainier a Climbing Guide by Mike Gauthier

Cascades Rock the 160 Best Multipitch Climbs of all Grades by Blake Herrington

The North Cascades by William Dietrich

Mont Blanc the Finest Routes: rock, snow, ice and mixed by Philippe Batoux

Mont Blanc: 5 routes to the summit by Franȯis Damilano

Swiss Rock Granite Bregaglia: a selected rock climbing guide by Chris Mellor

Canadian Rock select climbs of the west by Kevin McLane

Sport climbs in the Canadian Rockies by John Marin and Jon Jones

Mixed Climbs in the Canadian Rockies by Sean Isaac

For more information about the person who took these photos, you can read Gilmour’s obituary in the American Alpine Journal.

The Secret History of the Ice Axe

Mountaineering Boots of the early 20th century

A tale of horror and woe

by Allison Albright

Modern mountaineering boots are made to be comfortable, lightweight, insulated and waterproof. They're constructed of nylon, polyester, Gore-Tex, Vibram and involve things like "micro-cellular thermal insulation" and "micro-perforated thermo-formable PE." This technology costs anywhere from a couple hundred dollars to over $1000 and makes it much more likely for a mountaineer to keep all their toes.

We didn't always have it so good.

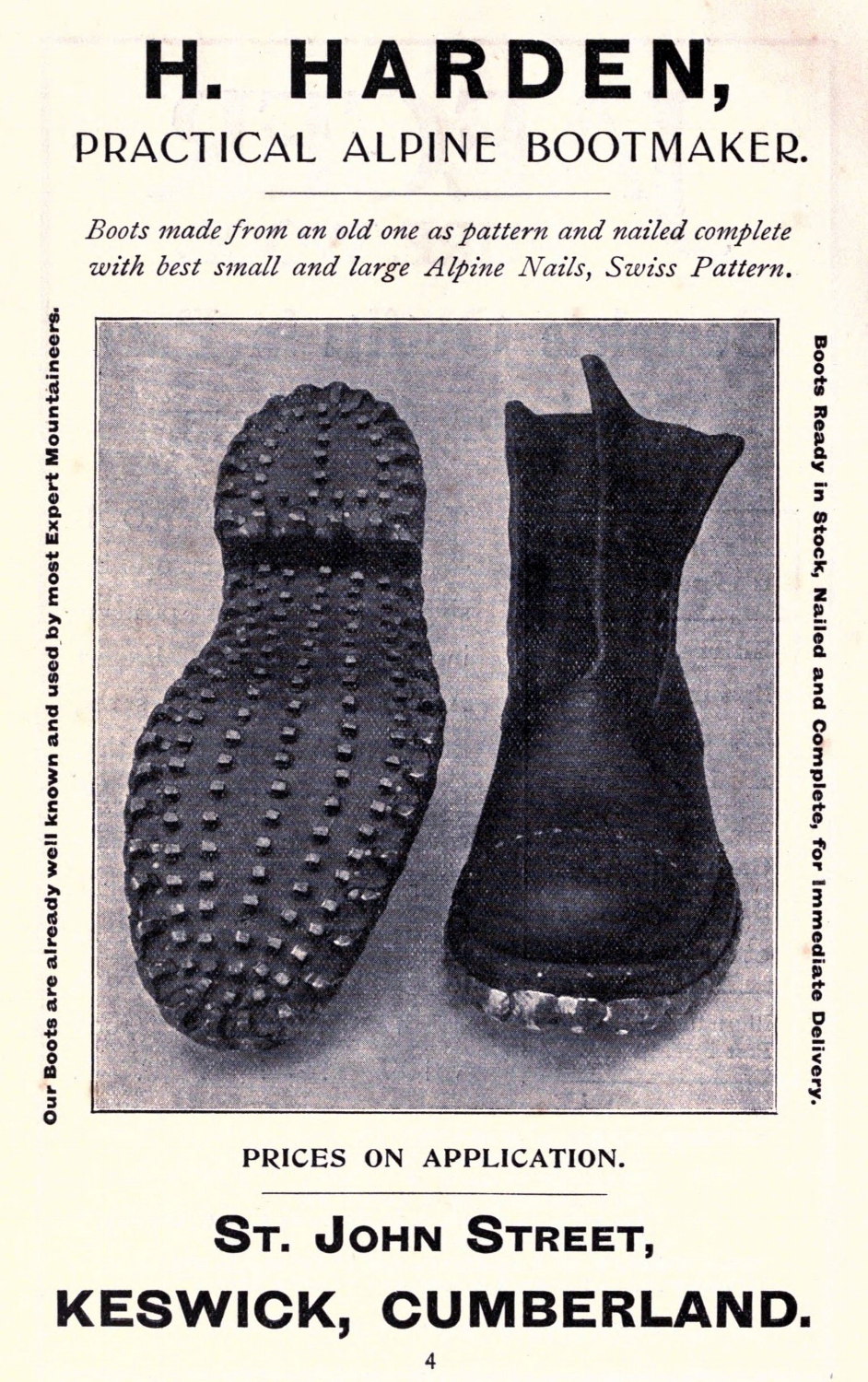

Mountaineering boots circa 1911.

By H. Harden - Jones, Owen Glynne Rock-climbing in the English Lake District, 1911, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9433840

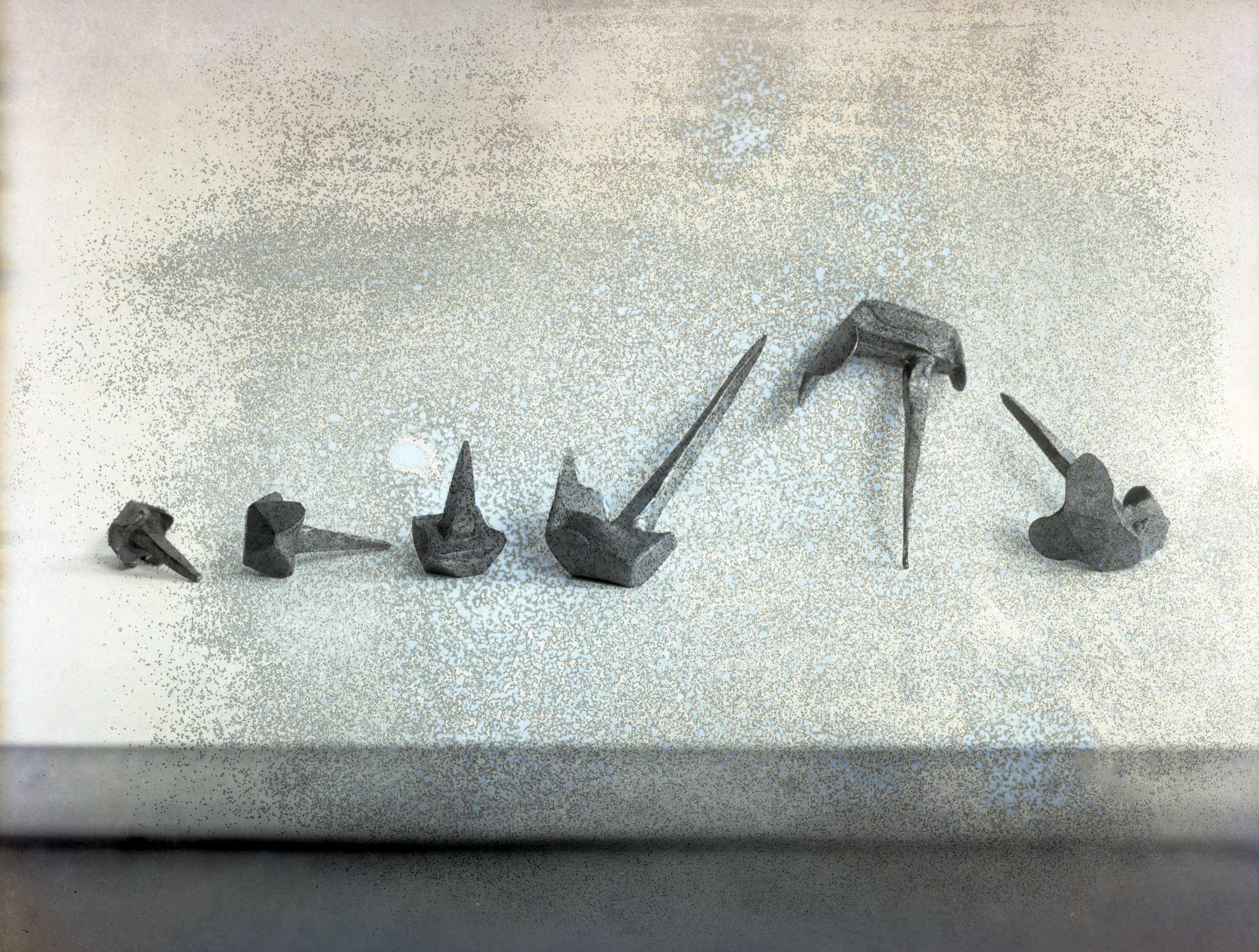

Early mountaineering boots were made of leather. They were heavy, and to make them suitable for alpinism it was necessary for climbers to add to their weight by pounding nails, called hobnails, into the soles.

“The very best boot is without a doubt the recognized Alpine climbing boot. Their soles are scientifically nailed on a pattern designed by men who understood their business; their edges are bucklered with steel like a Roman galley or a Viking’s sea-steed. No doubt they are heavy, but this slight inconvenience is forgotten as soon as the roads are left.”

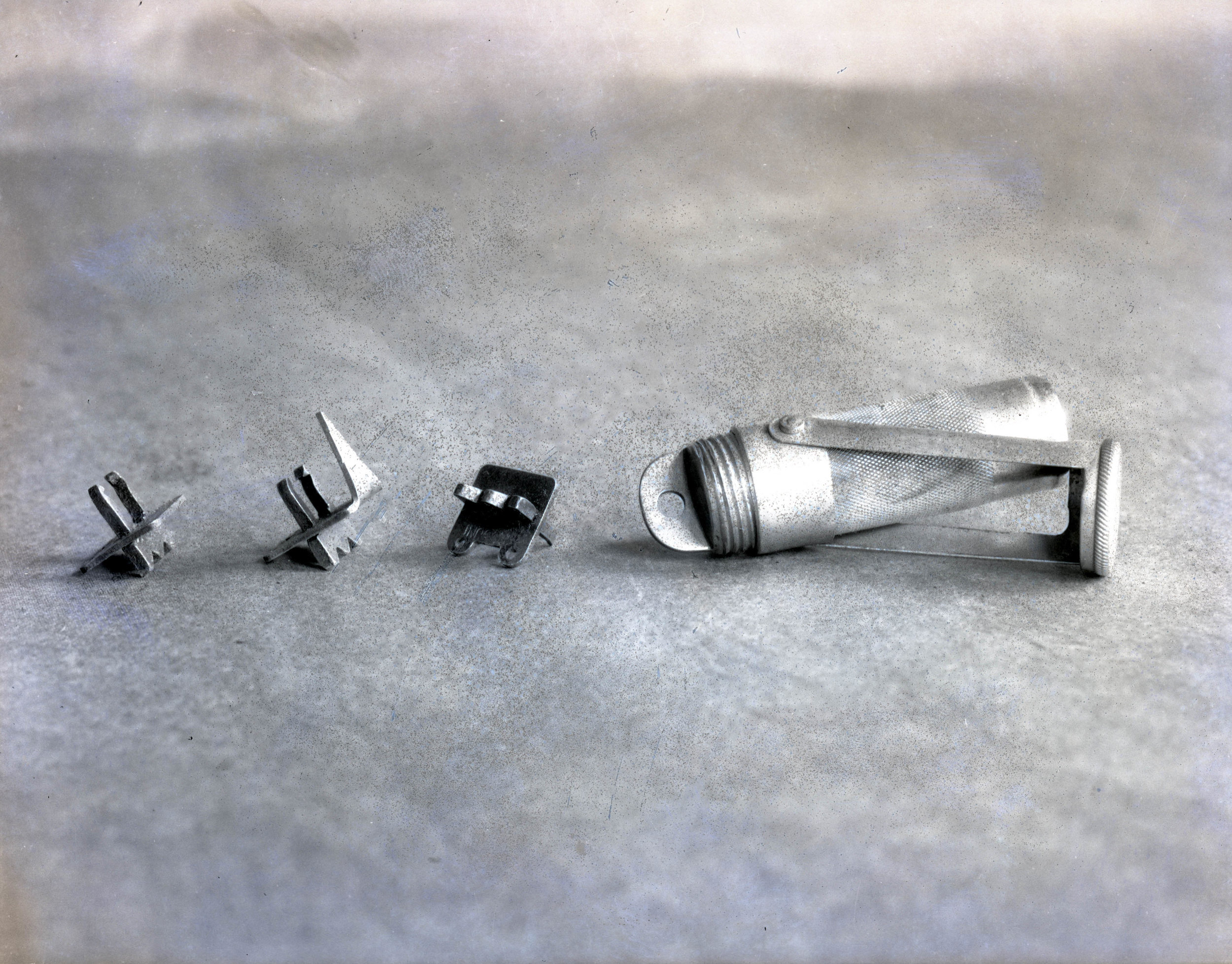

Tricouni nails were a recent invention in 1920 and could be attached to mountaineering boots to provide traction. They were specially hardened to retain their shape and sharpness.

Illustration from Mountain Craft by Geoffrey Winthrop Young. New York, 1920.

Illustration of boot nails from Mountaineering Art by Harold Raeburn, 1920.

In 1920 a pair of climbing boots went for about £3.00 - the equivalent of $28.63 in 2017 US dollars. However, climbers got much less for their money than we get out of our modern boots.

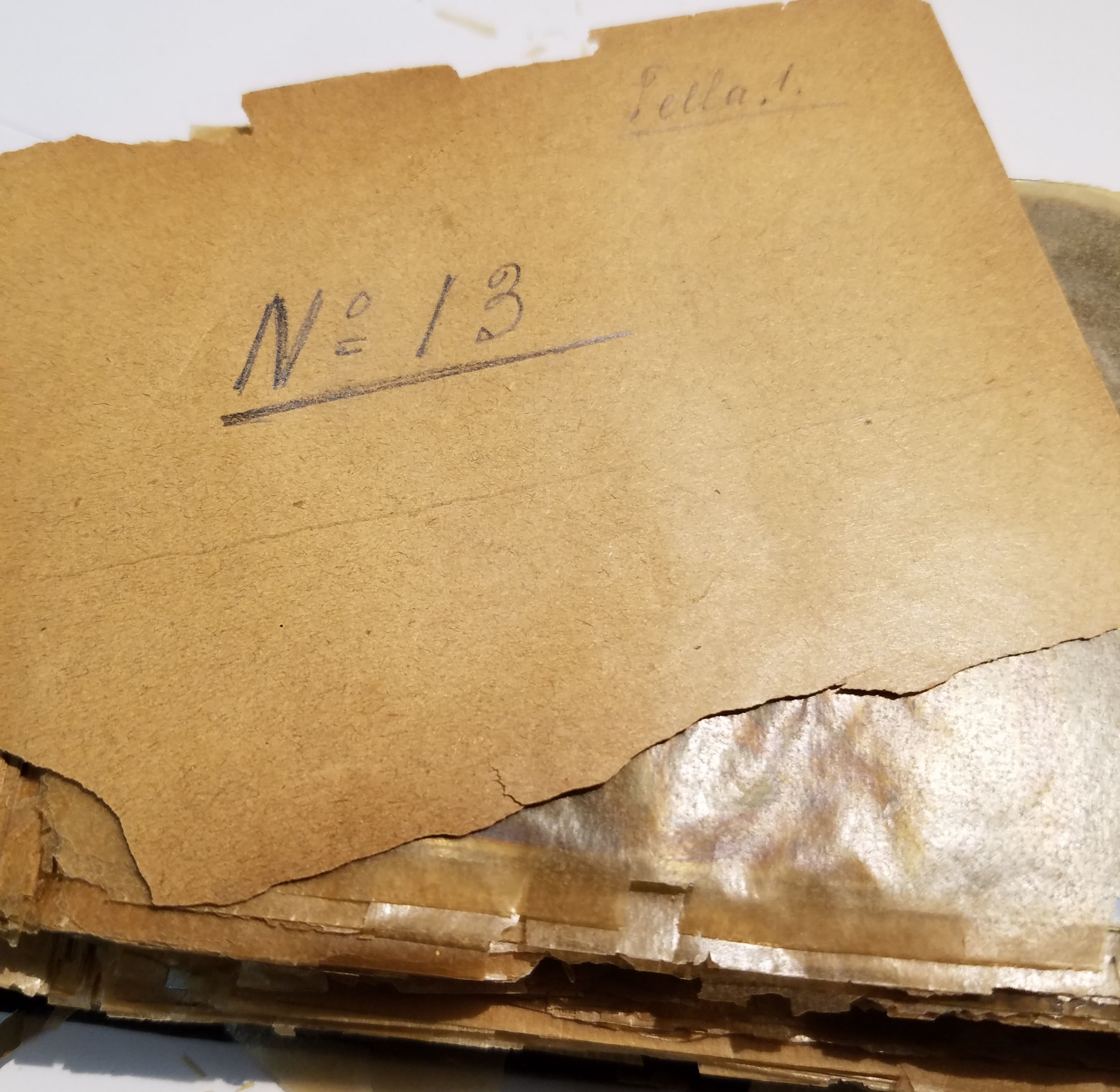

Original hobnails, stored in a reused box

“There is no use asking for “waterproof” boots; you will not get them.”

In addition to being heavy, the boots were not waterproof. Mountaineers had to apply castor oil, collan or melted Vaseline to the boots before each trip. This kept the boots flexible and also kept at least some water out. Animal fats were also an option, but they had a strong, unpleasant smell and would decompose, causing the leather and stitching of the boots to rot as well.

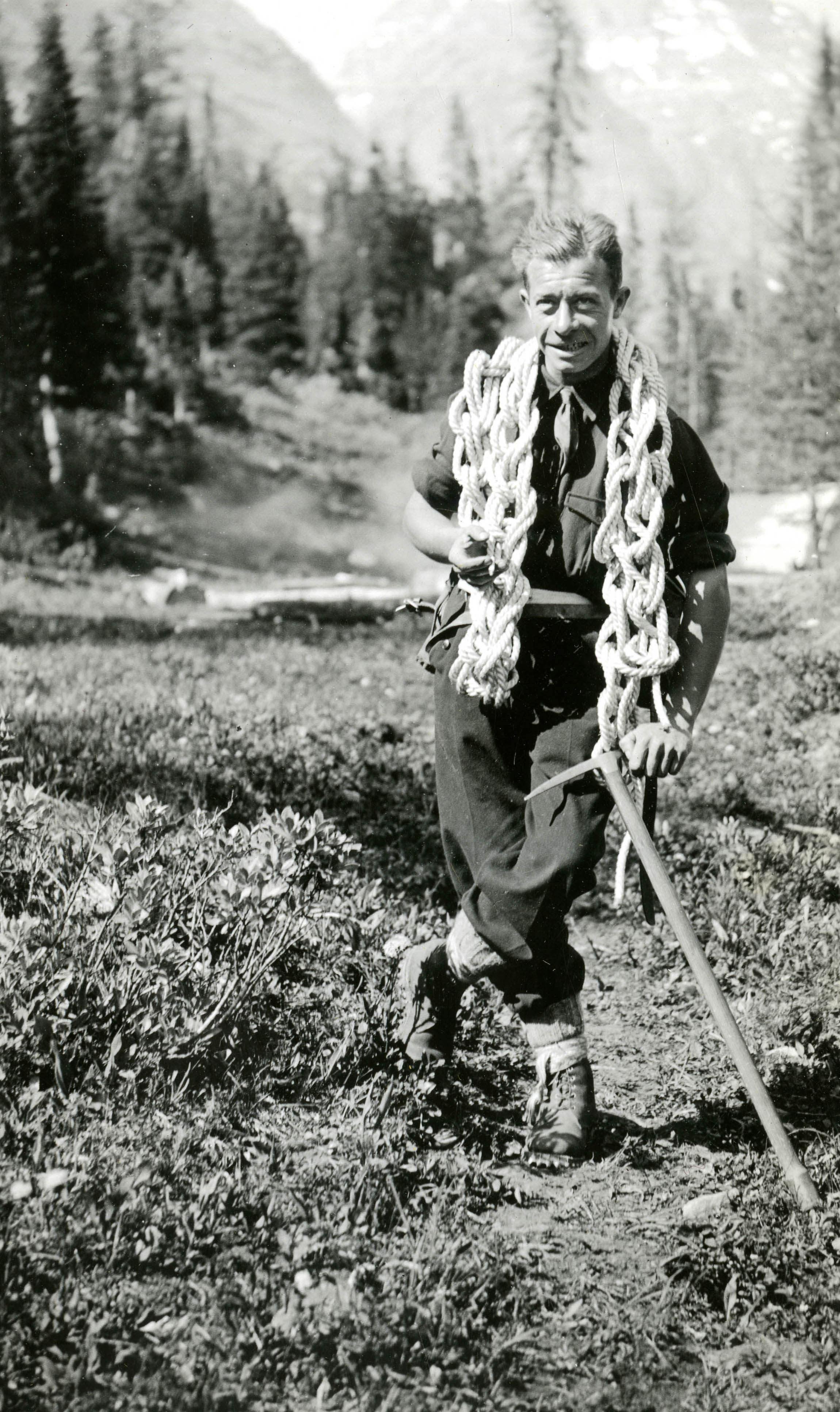

Hobnail boots

in action on Mumm Peak, Canada. 1915

Photo from our Andrew James Gilmour collection.

Boots with linings were not recommended for mountaineering, as the linings were usually made of wool and other natural fibers which were slow to dry when inside a boot. Wet boot linings, either due to water or snow leakage or human sweat, were a major cause of frostbite resulting in the loss of toes.

When not in use, the boots needed to be stuffed with dry paper, hay, straw or oats which were changed at intervals to ensure that all moisture was absorbed. If they weren't stuffed in this manner on an expedition, they were in danger of freezing and twisting out of shape.

A pair of worn hobnail boots set to dry over a fan in about 1920. This luxurious set-up was possible because the mountaineer was staying in a Swiss hotel.

Photo from our Andrew James Gilmour collection.

“Look with suspicion upon the climber who says he wears the same pair of boots without re-soling for three or four years. It will probably be found that his climbing is not of much account, or he is wearing boots which have badly worn and blunted nails, with worn-out and nail-sick soles, a worse climbing crime if he proposes to join your party, than if he were to wander up the Weisshorn alone.”

Crampons

Today crampons are made of stainless steel and weigh about 1 to 2 lbs. They can be bolted or strapped to the boot. In the early 20th century, crampons were made of steel or iron. They were strapped to the boot with hemp or leather straps passed through metal loops attached to the frames. Surprisingly, they didn't weigh too much more in the 1920s than they do today.

They could be bought in a variety of configurations, including models ranging from four to ten spikes. Mountaineers who recommended their use wrote that good crampons should have no fewer than eight spikes which should not be riveted to the frame. The crampons also should not be welded anywhere and the iron variety were likely to break if any real work were required of them.

A steel crampon with eight spikes and hemp and leather straps - ideal!

From the American Alpine Club Library archives

Good footwear is still one of the most important aspects of any trip. We're extremely grateful boot technology has advanced so much.

Care and Handling of Archival Nitrate Negatives

by Allison Albright

Nitrate film base was developed in the 1880s and was the first plasticized film base available commercially. It enabled photographers to take pictures under more diverse conditions, and its flexibility and low cost was partially responsible for making photography affordable and accessible to amateur consumers as well as professionals. It was widely used from the 1890s until the 1950s.

An album of nitrate negatives circa 1900

Nitrate negatives also happen to be mildly toxic and somewhat volatile. Because the material is the same chemical composition as cellulose nitrate (also known as flash paper or guncotton), which is used in munitions and explosives, it is incredibly flammable and prone to auto-ignition. It was also used in motion picture film in the early 20th century and was responsible for several movie theater fires during that era.

Below are some negatives in the early stages of deterioration.

As if the danger of combustion wasn’t enough, nitrate negatives also emit harmful nitric acid gas as they deteriorate, meaning that we need to use safety precautions such as respirators and latex gloves when handling these negatives.

HNO3 + 2 H2SO4 ⇌ NO2+ + H3O+ + 2HSO4

Nitric acid is considered a highly corrosive mineral acid.

Nitrate negatives usually deteriorate in just a few decades, making them an extremely unstable storage medium. As they deteriorate, the image begins to fade and the negative turns soft and gooey, causing it to weld itself to whatever it’s stored with, resulting in the loss of the image.

A clump of badly deteriorated negatives stuck together forever

When good negatives go bad - a negative in the process of becoming goo

Like most archival collections containing materials created from about 1890 to the early 1950s, the AAC’s collection includes some nitrate film negatives. For most of their lives, these negatives have been stored in a cold, temperature controlled area. We’re digitizing these negatives in order to capture the images and make them accessible to the public before we put them in deep freeze. The best way to preserve and store nitrate negatives for the long term is to freeze them to slow the process of deterioration and minimize the risk that they’ll start a fire.

Because of the unstable nature of nitrate negatives, some deterioration is to be expected. However, the vast majority of this collection is still in good shape. We've included a few selections below. Eventually, we’ll make all the images from our nitrate negatives available.

These photographs are taken from the collection of Andrew James Gilmour (1871-1941), an AAC member whose surviving photographs help inform our knowledge of the history of climbing and what the sport was like in the early 20th century.