It had all begun on an afternoon some nine months previous. Four of us were lying about relaxing after a particularly fine Teton climb when someone enthusiastically suggested, "Let’s climb the south face of McKinley next summer!” To attempt a new and difficult route on North America’s highest mountain seemed a most worthwhile enterprise; without further ado, we cemented the proposal with a great and ceremonious toast.

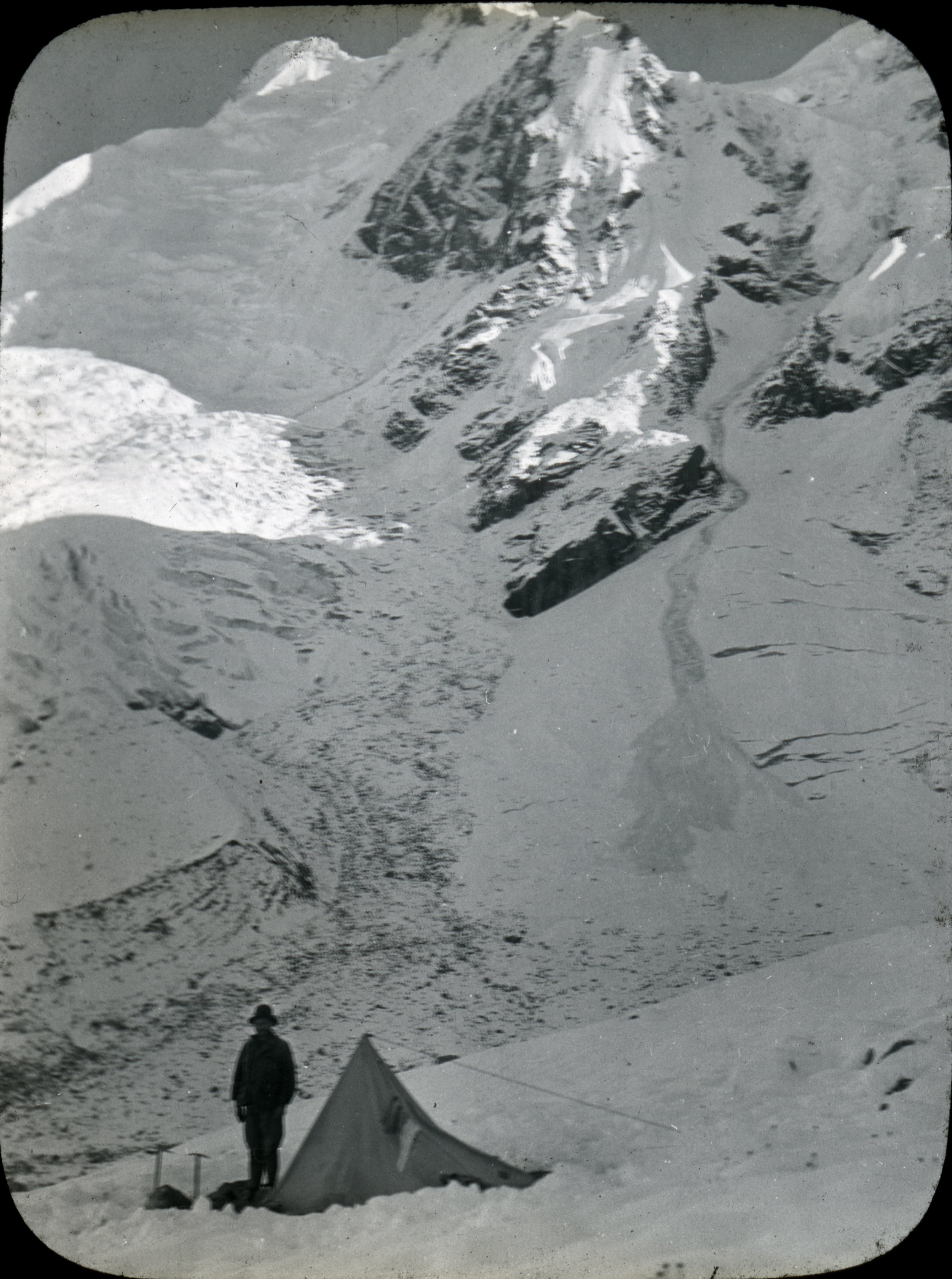

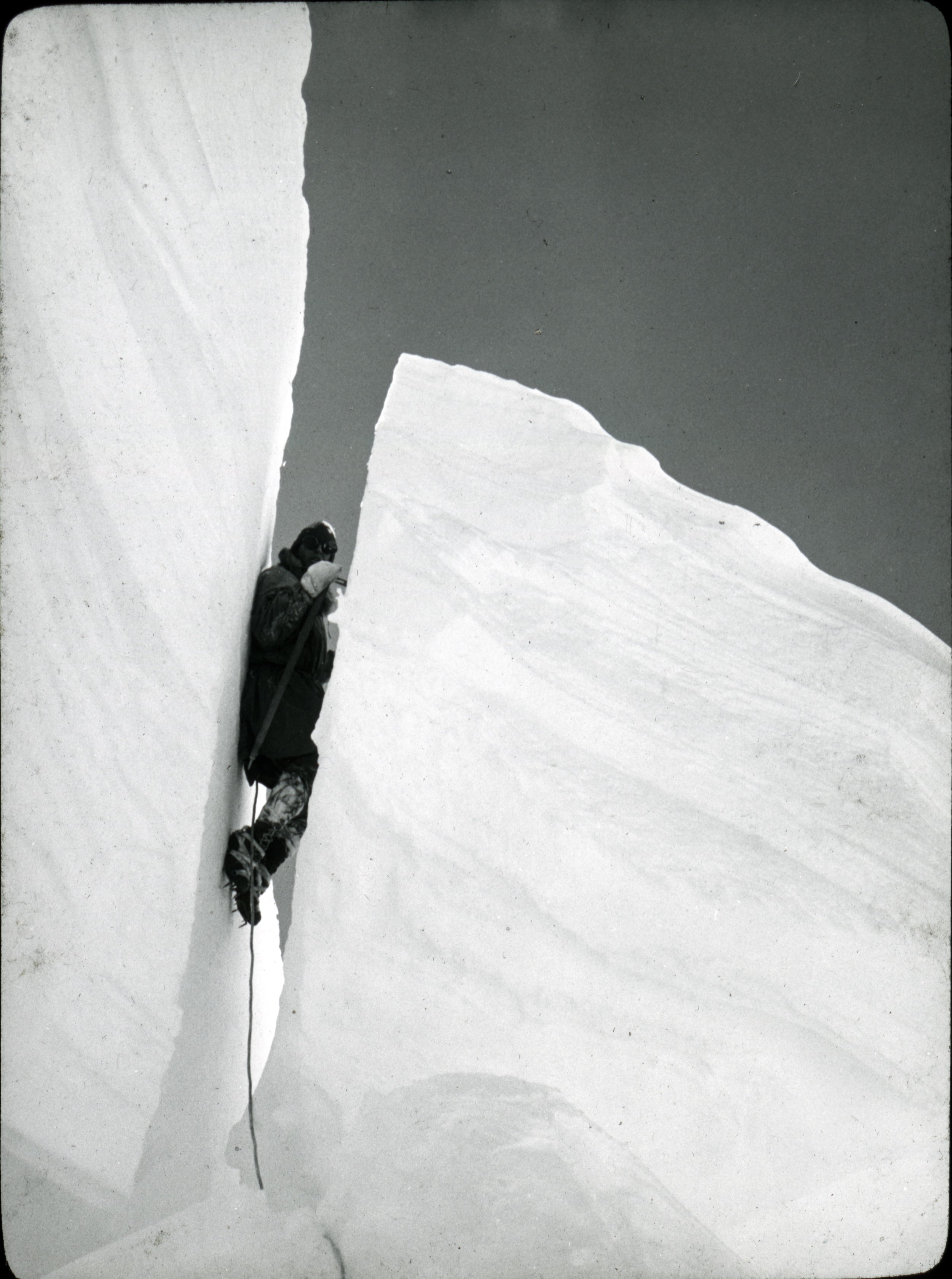

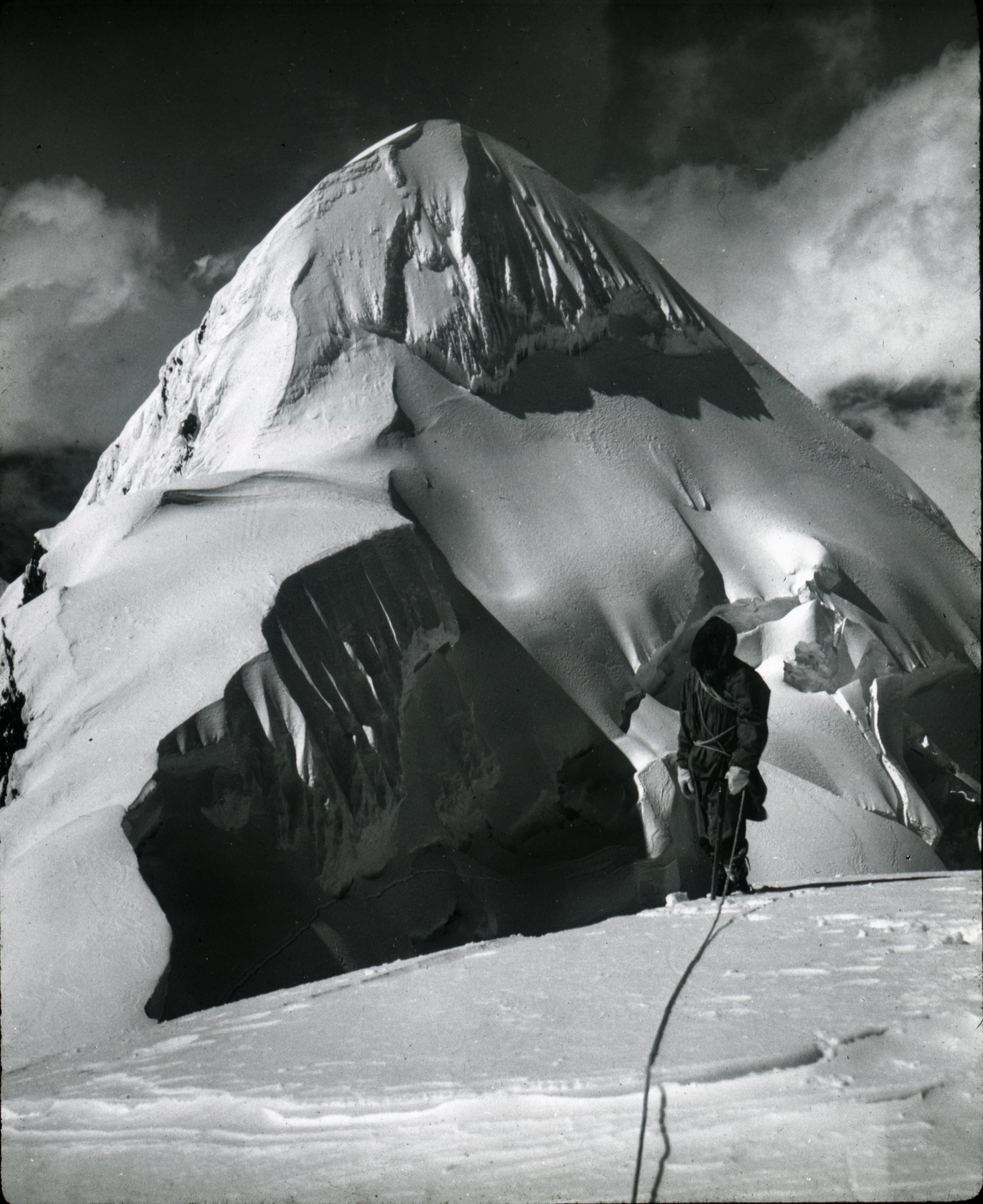

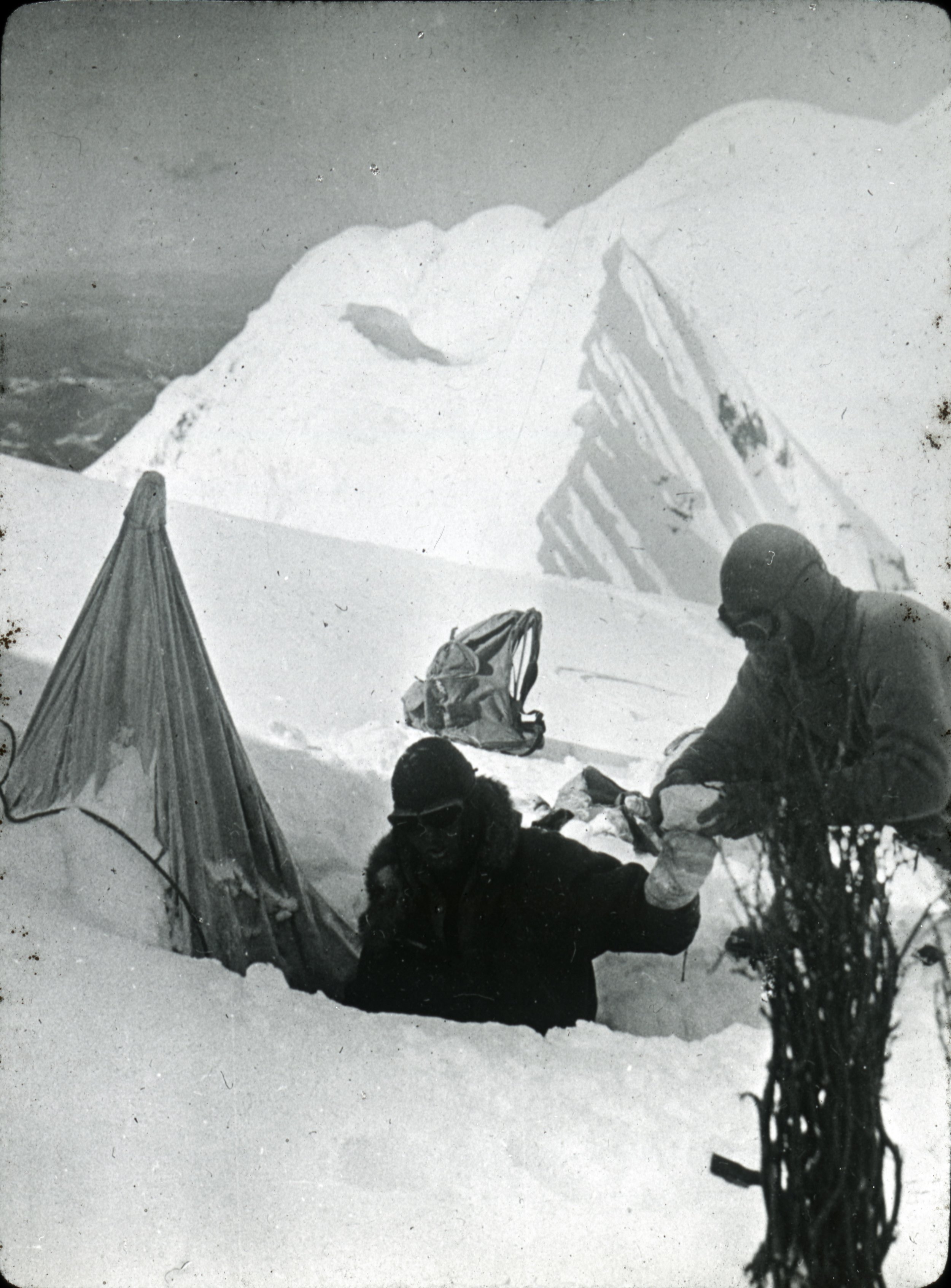

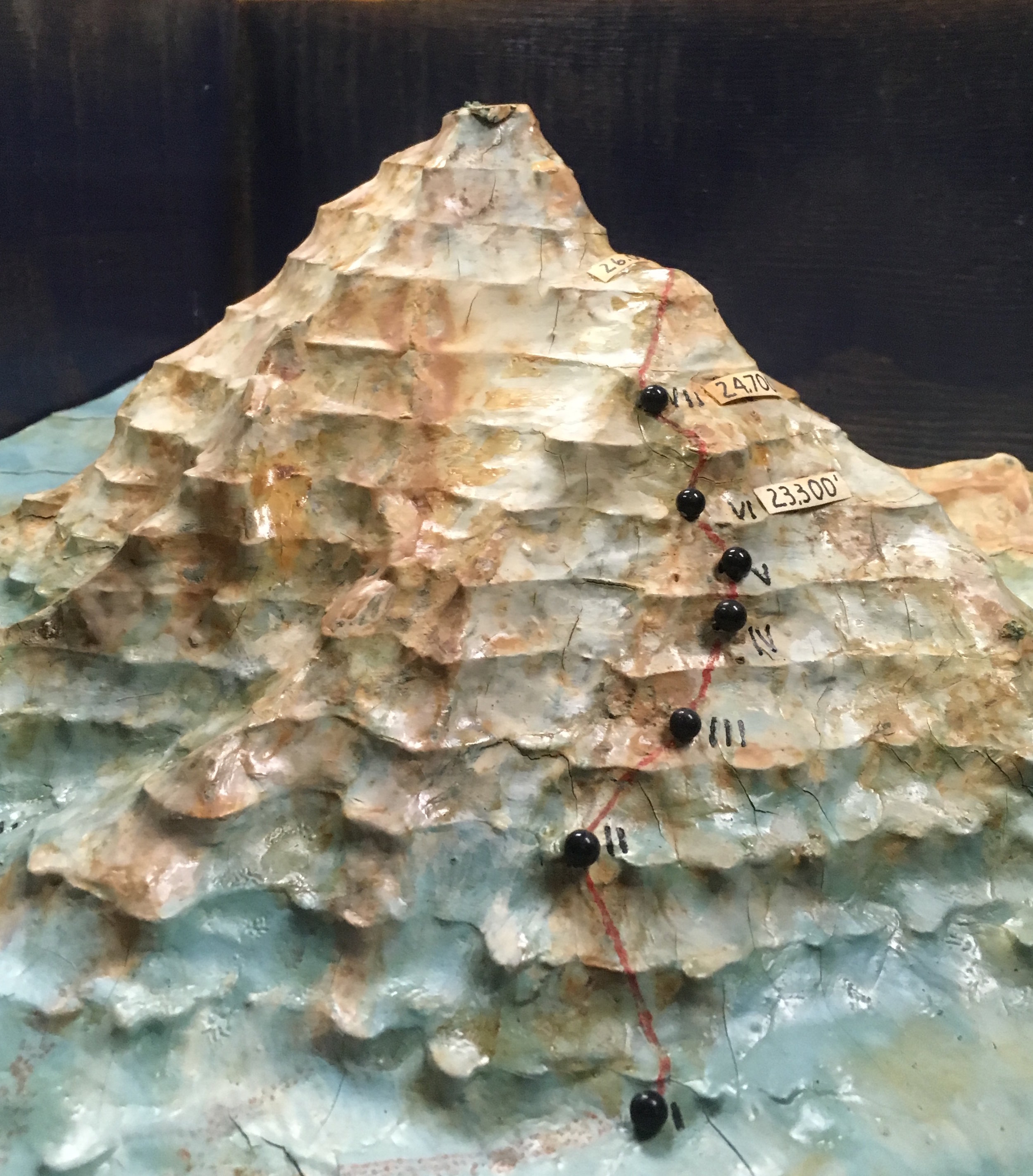

Gongga Shan (Minya Konka) 1932

by Eric Rueth

The Sikong Expedition in 1932 has to be one of the more unique mountaineering tales to have ever occurred. I and maybe others would argue that if there ever was a mountaineering expedition that should be turned into 1990’s style action-adventure movie starring Brendan Fraiser, this one would be it. There are too many interesting details to this expedition to fully capture in a blog post like this, so instead I’m going to give you a bare bones description and show you some of Terris Moore’s slides in an attempt to get you to read the American Alpine Club Journal articles about the expedition (linked below), and/or to read the entire book of the expedition (prologue through the epilogue), Men Against the Clouds. The pieces written by the expedition members themselves are really the only pieces of writing that do this expedition justice.

The Sikong Expedition consisted of four Americans, Jack Young, Terris Moore, Arthur Emmons, and Richard Burdsall. These were the four remaining members of a larger Explorers Club expedition that was meant to take place but dissolved due to various delays and complications created by global events. One of the global events was the Japanese invasion of Shanghai which led Young, Moore, Emmons, and Burdsall to briefly become a part of the American Company of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps.

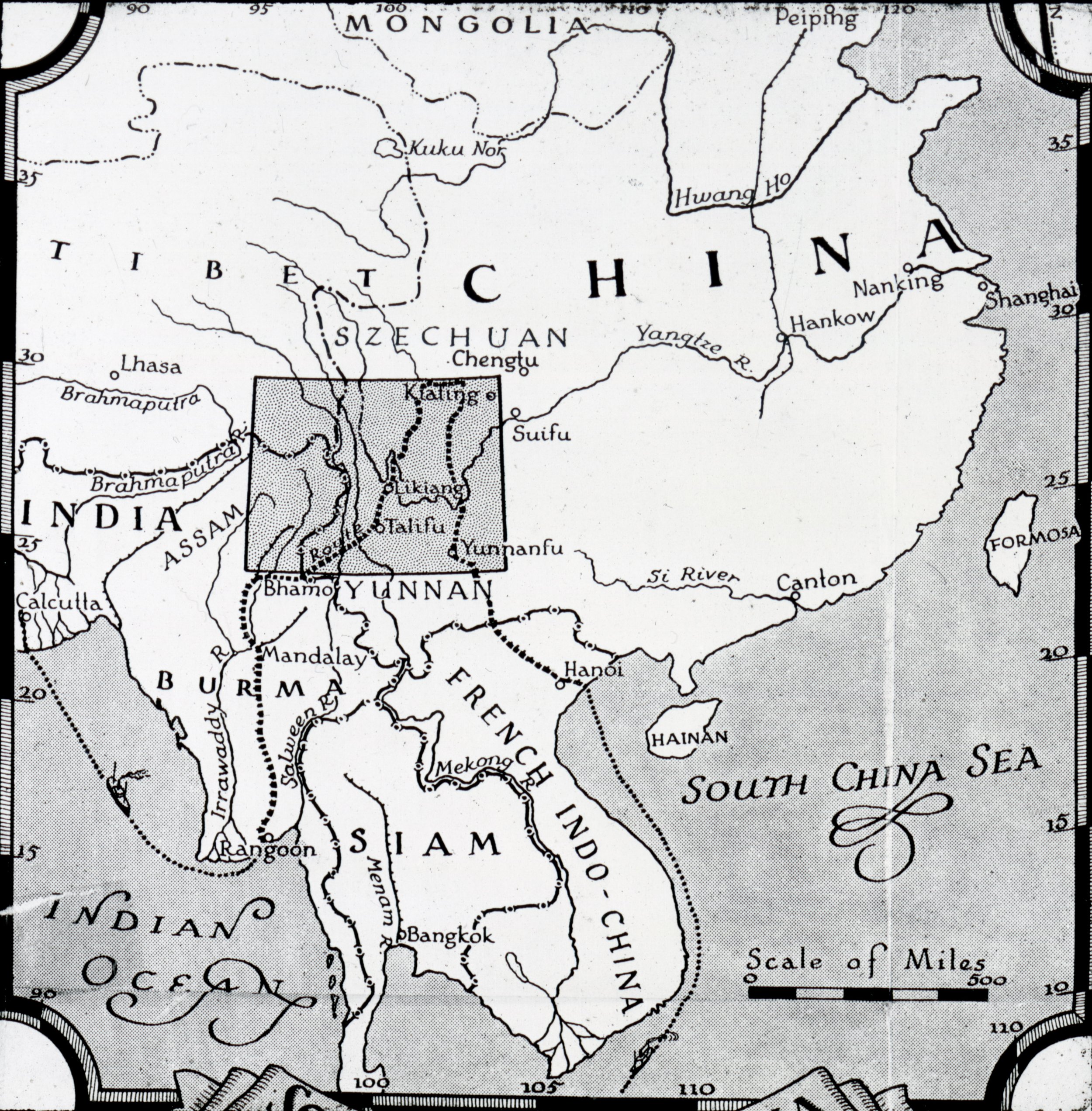

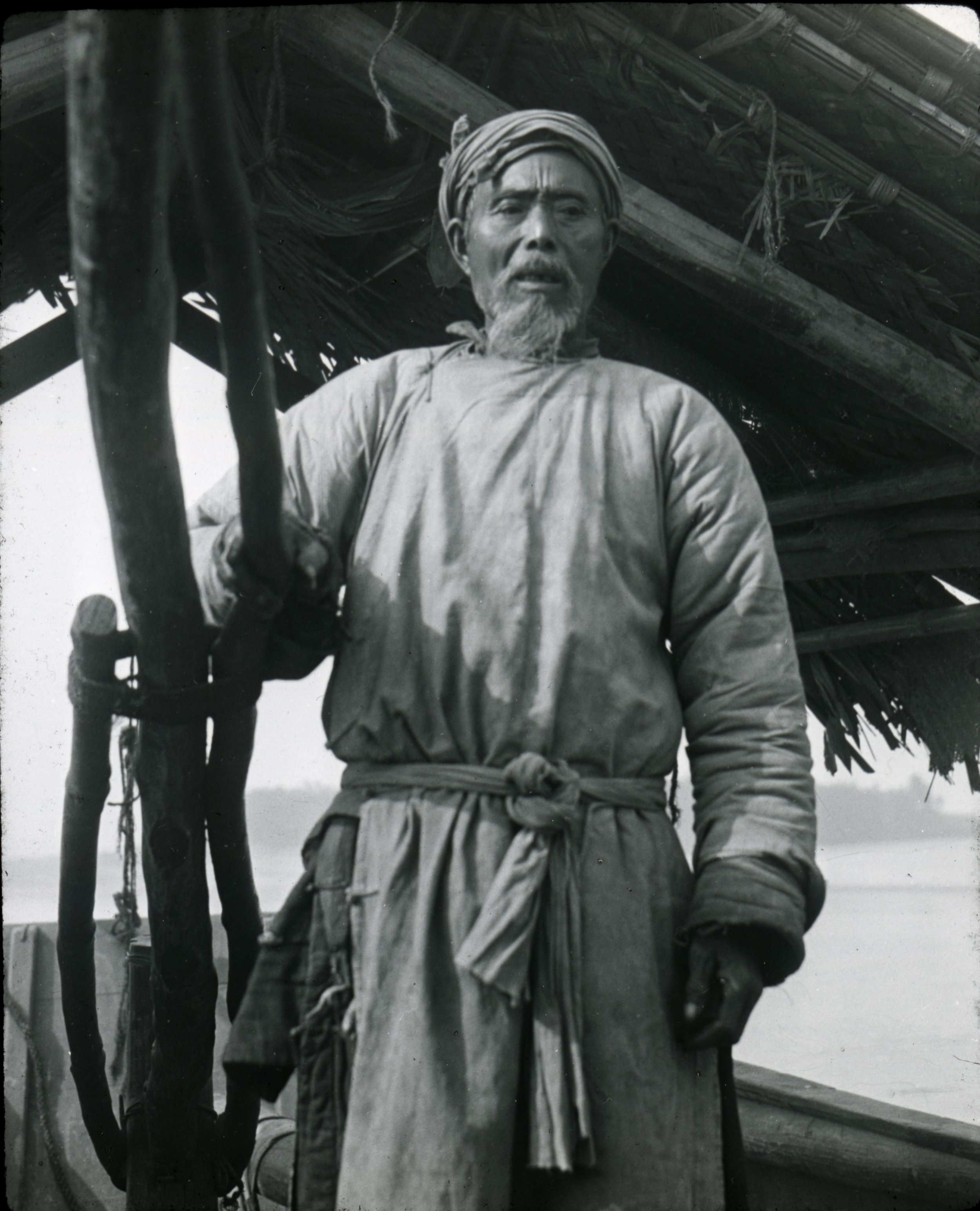

After the dissolution Lamb Expedition to Northern Tibet, the first step of the newly formed Sikong Expedition was a twenty day journey up the Yangste River that featured rough waters, beautiful gorges and potential for pot shots from bandits on the river banks.

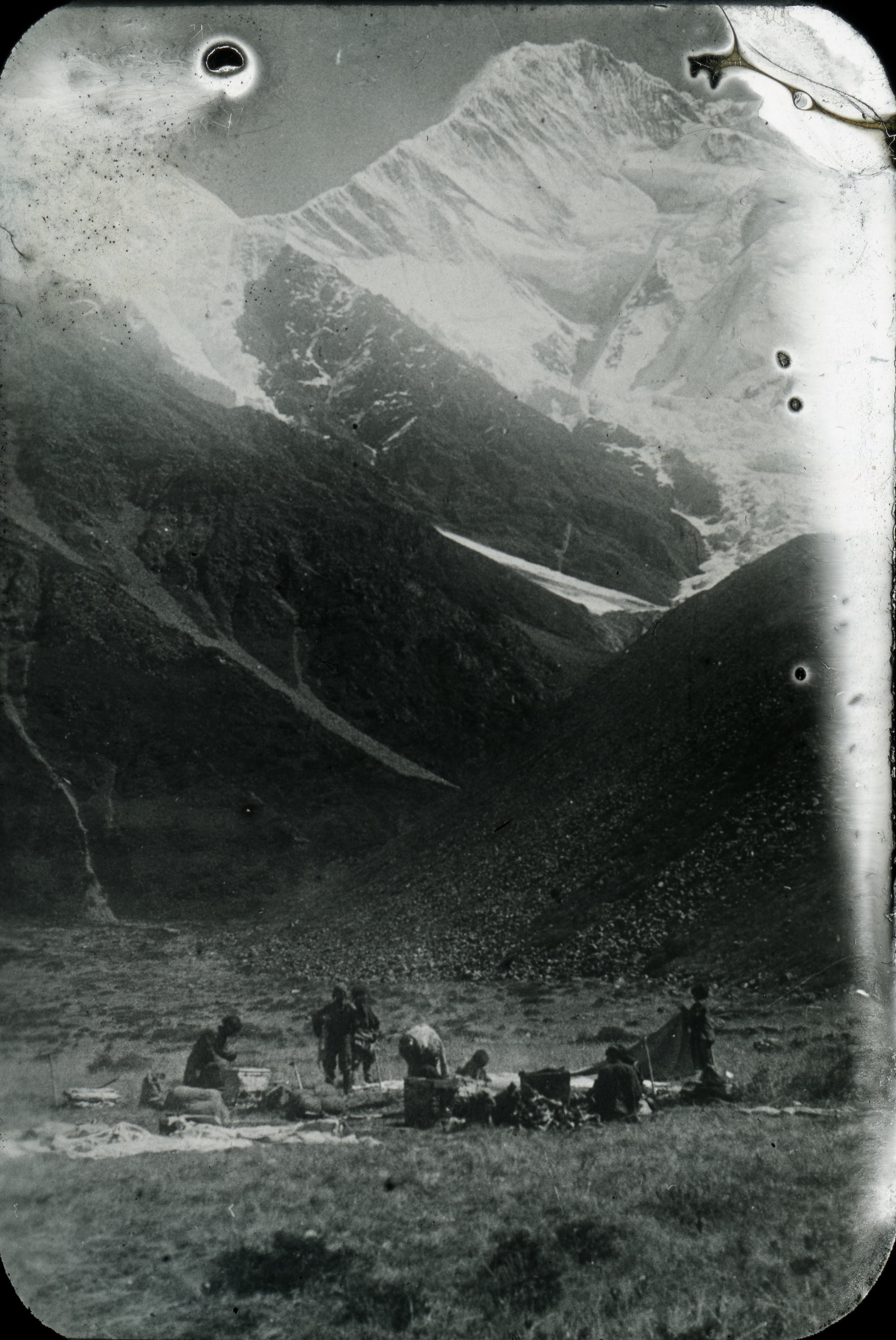

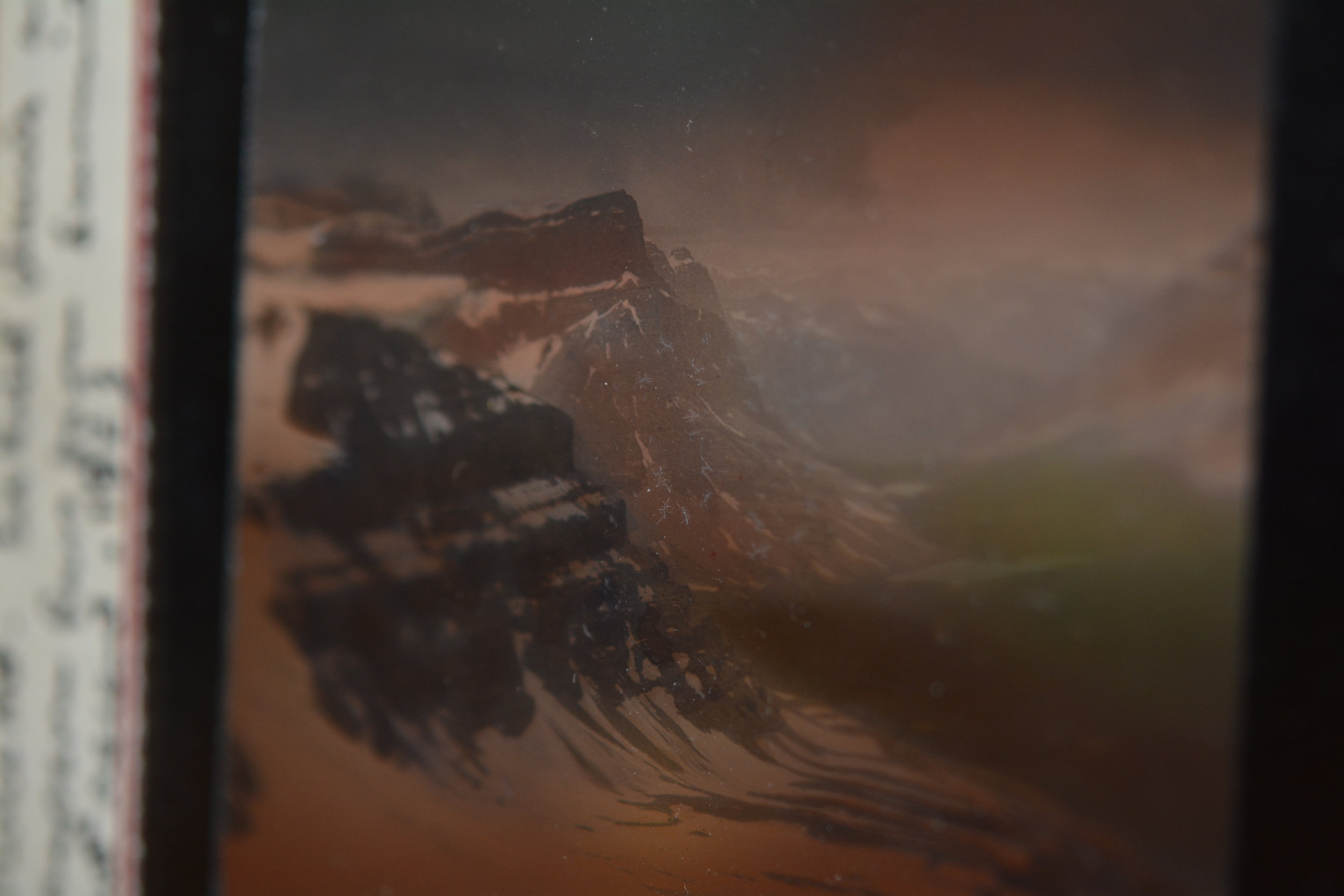

The Sikong-Szechuan region was still relatively unknown to the west and the purpose of the original expedition was to explore survey the region and gather samples of flora and fauna along with an attempt on Gongga Shan. The explorer’s spirit lived on in the Sikong Expedition. Thirty pages of appendices and one AAJ Article document their efforts. Below are two slides that not only shows the expedition doing some survey work but also shows how photographs and slides can degrade over time! If your interested in degrading photographs check out this previous library blog post.

Part of the reason for surveying the region and the mountain specifically was that at the time calculations of its height ranged anywhere from 16,500’ to 30,000’. The Sikong Expedition measured Gongga Shan’s height to be 24,891’ which is only 100’ off of the mountain’s current measured height of 24,790’.

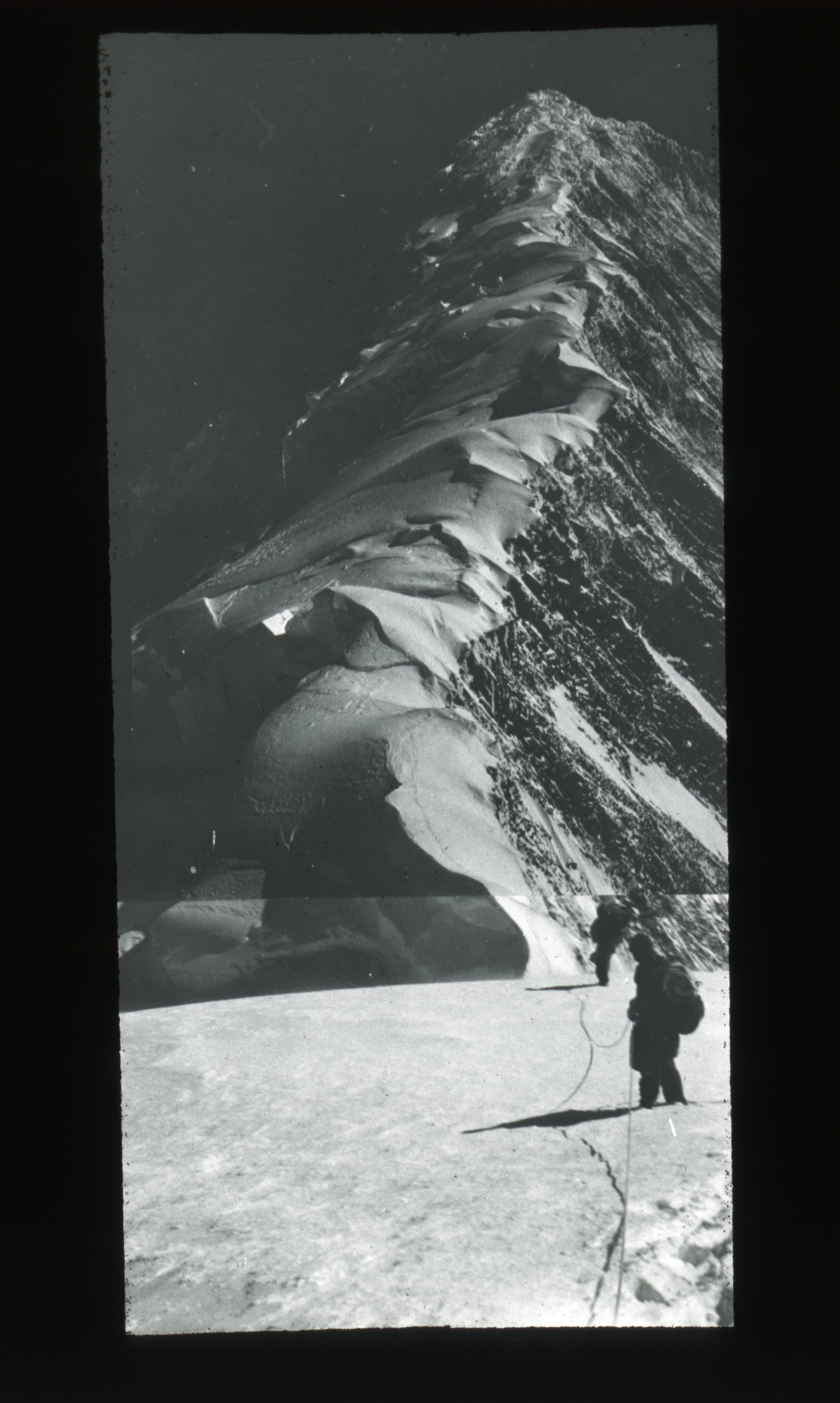

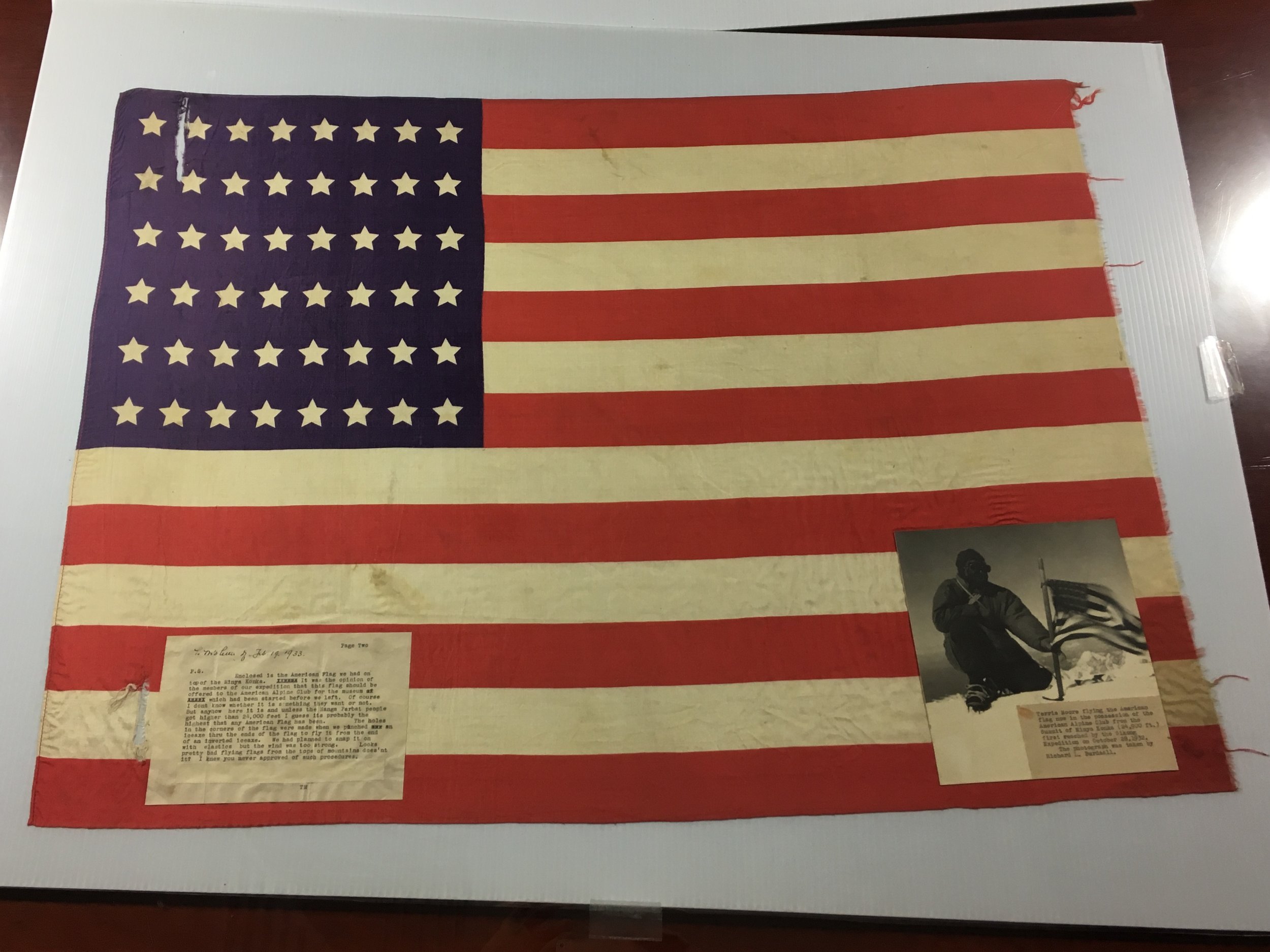

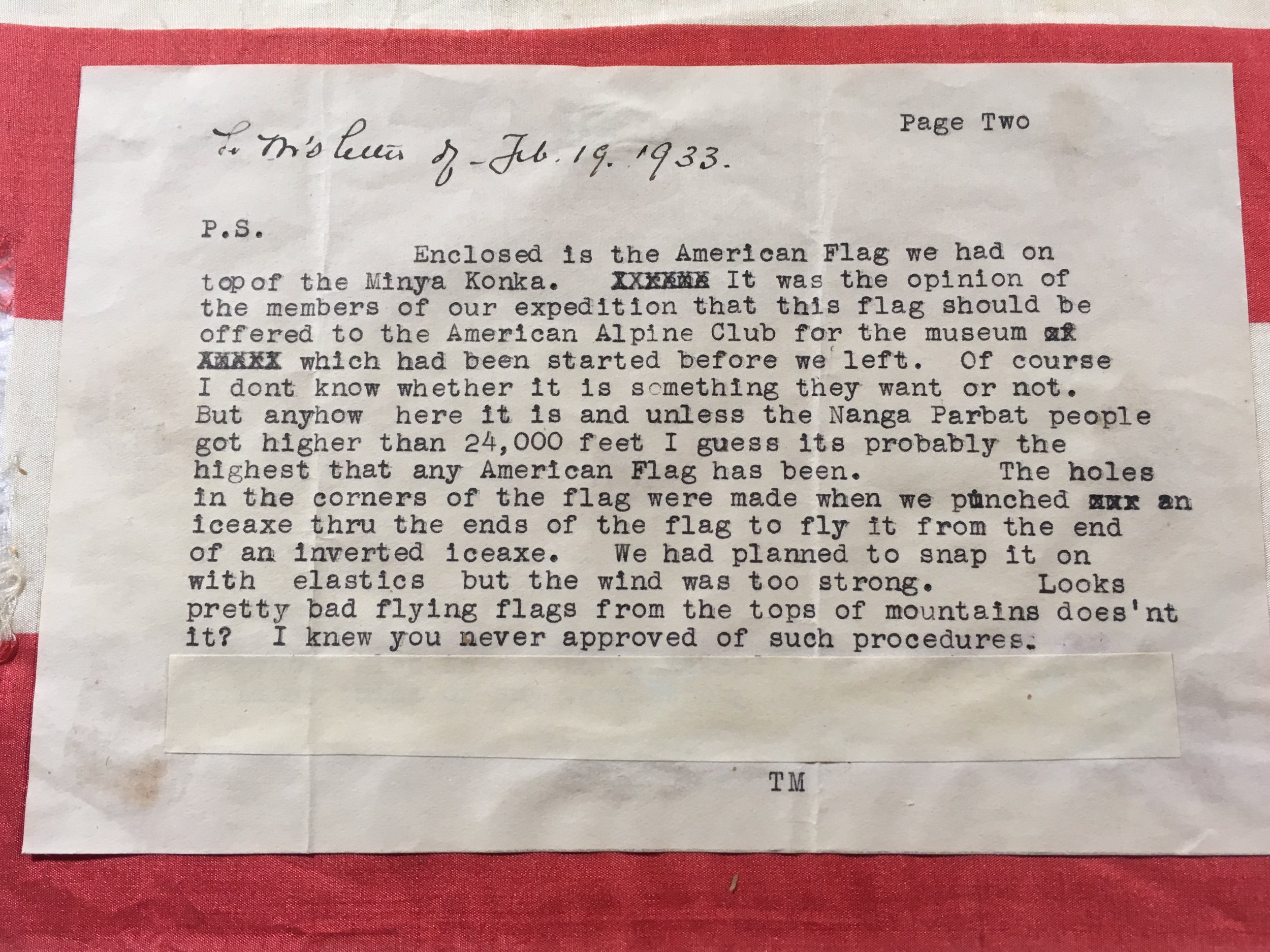

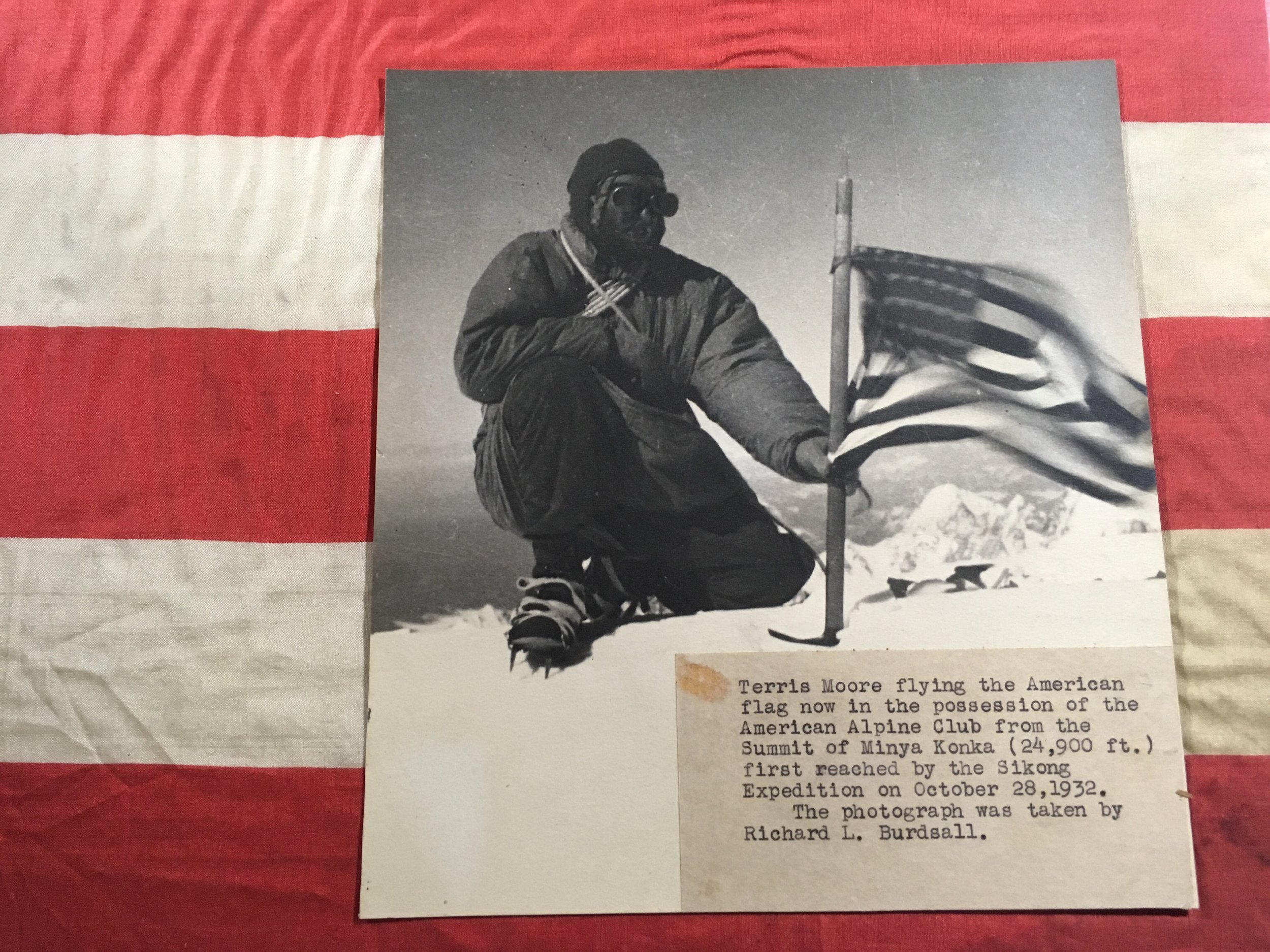

After weeks of acclimatization, moving supplies, and setting up camps, no high-altitude porters and with crevasse falls along the way; Moore and Burdsall attained the summit on October 28, 1932. Below are two of the dozens of photos taking while on the summit. Photographs were taken with the Chinese flag and the American flag. The American flag (48 stars) carried to the summit currently resides here at the American Alpine Club Library. Due to wind, an ice axe had to be pushed through the flags to keep them attached and flying for the summit photos.

What makes this expedition such an amazing feat is the twists and turns that take place in the story. The expedition in a sense never should have happened after the Lamb Expedition dissolved. Under normal circumstances it is likely that everyone would have headed home and planned to try again at a different time. Instead, four members remained in large part due to the Great Depression and being told that their money would fair them better in China and that there likely wouldn’t be work for them if they returned to the States. The style that the mountain was summited was more akin to modern expeditions than it was to the siege the mountain strategy that tended to be the norm for the day. Despite not receiving much plaudits at the time, Gongga Shan was the highest summit reached by Americans at the time but the expedition was able to help fill in one of the few remaining blanks on the map.

If you’re an American Alpine Club member you can checkout Men against the clouds by logging into the AAC Library Catalog.

And regardless of if you’re an AAC member, you can find AAJ articles written about the expedition by following the links below:

Terris Moore’s AAJ article about the climb

Arthur Emmon’s AAJ article about the survey work

A short article by Nick Clinch that concisely summarizes the expedition

The Andrew J. Gilmour Collection

by Allison Albright

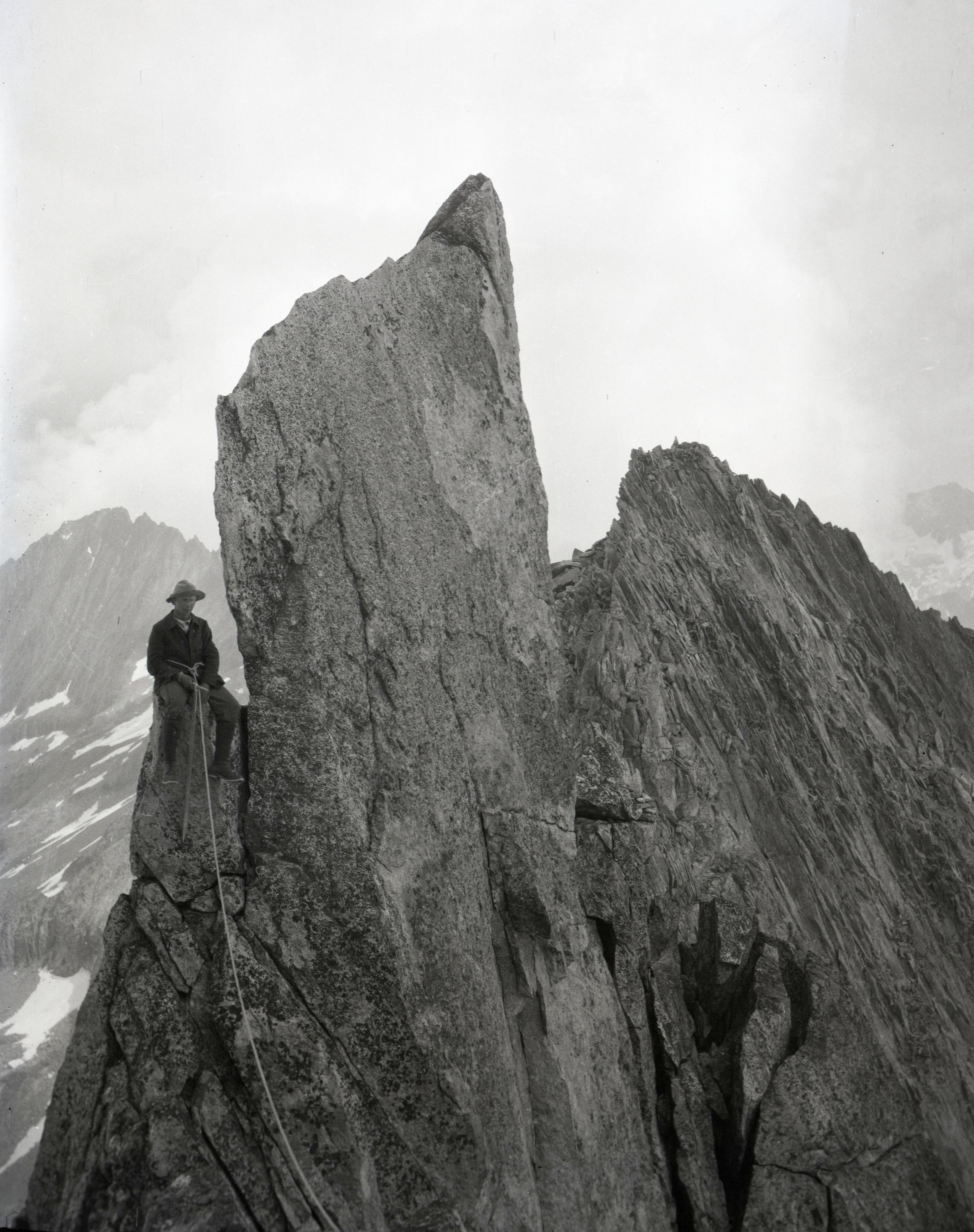

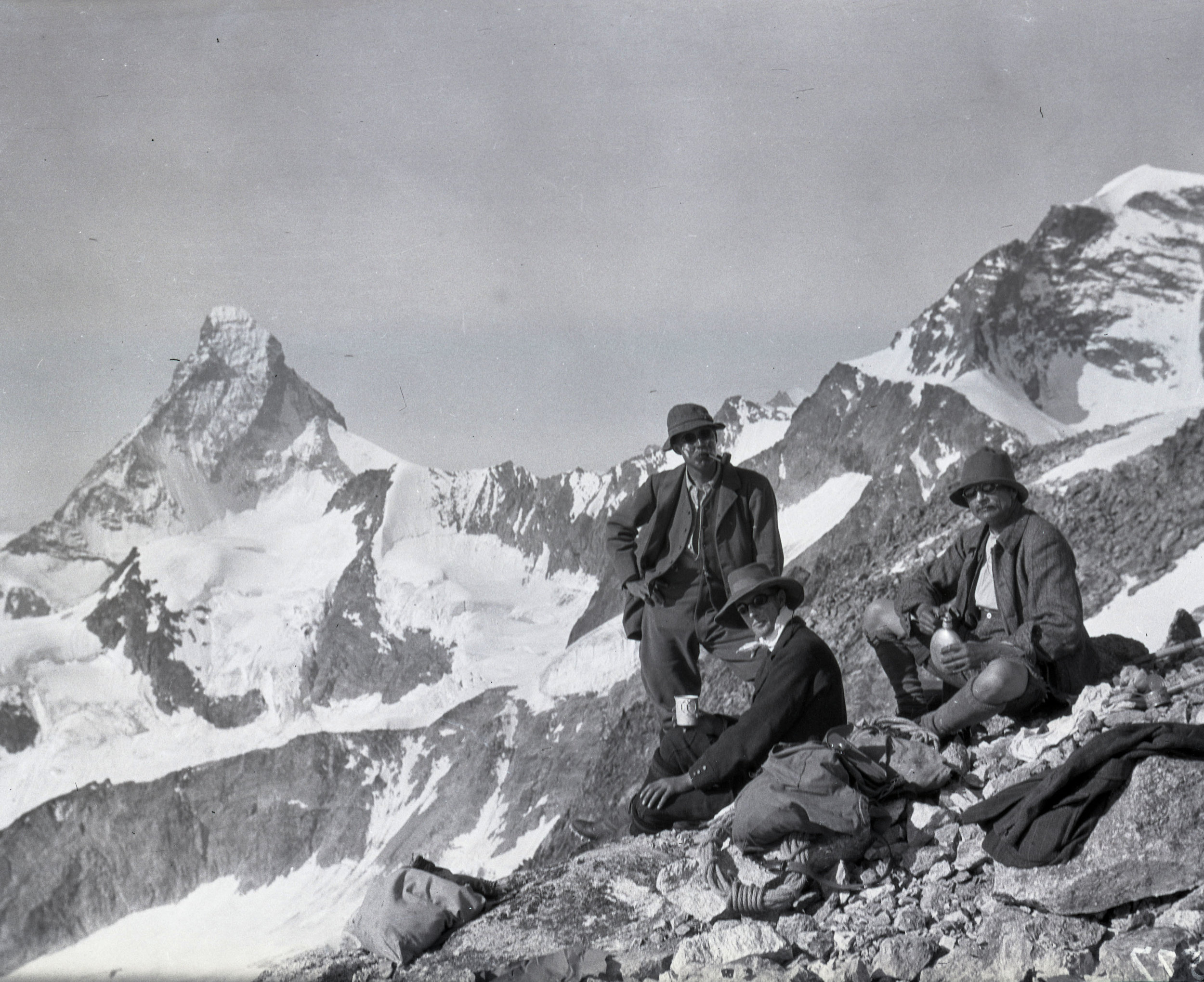

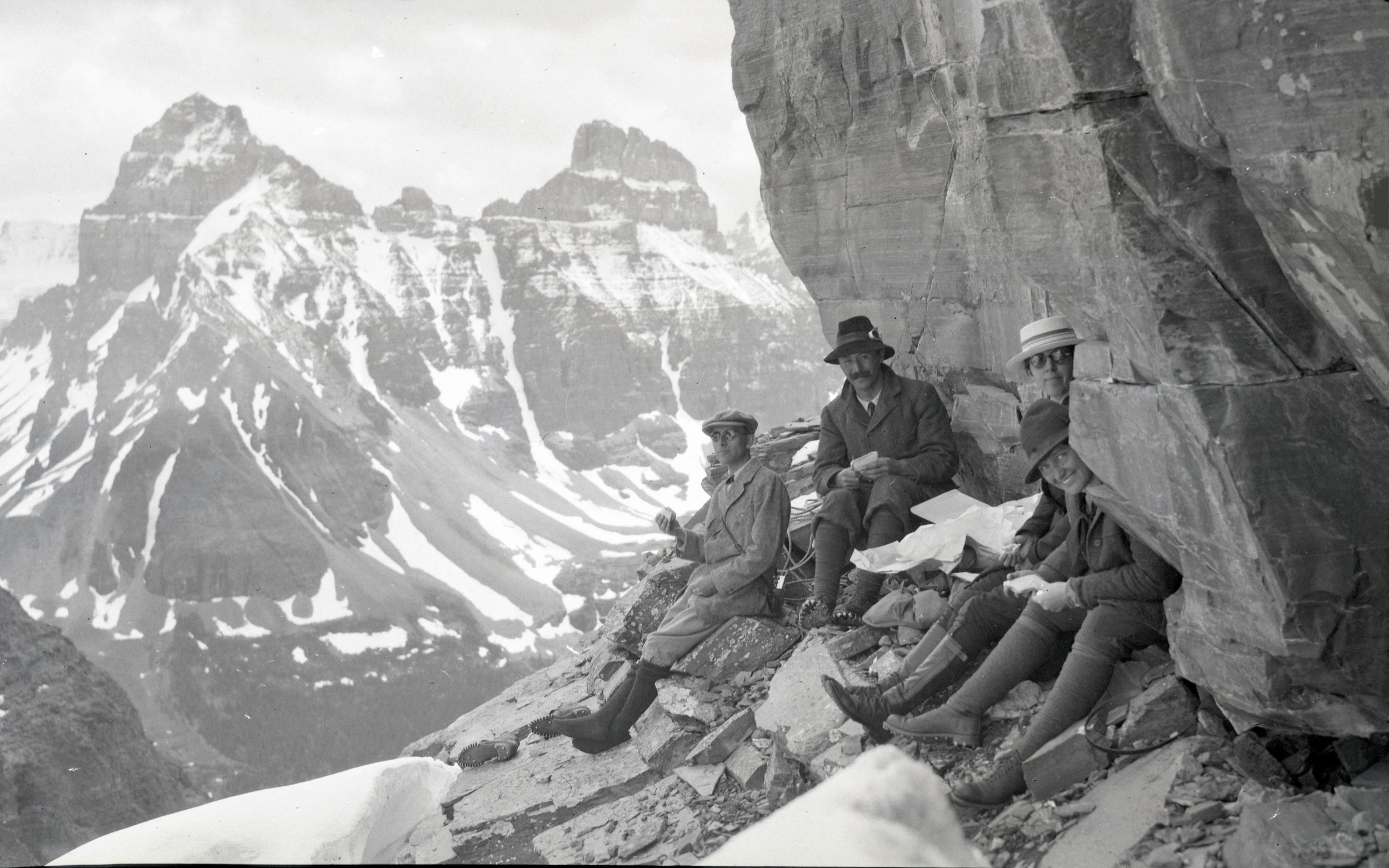

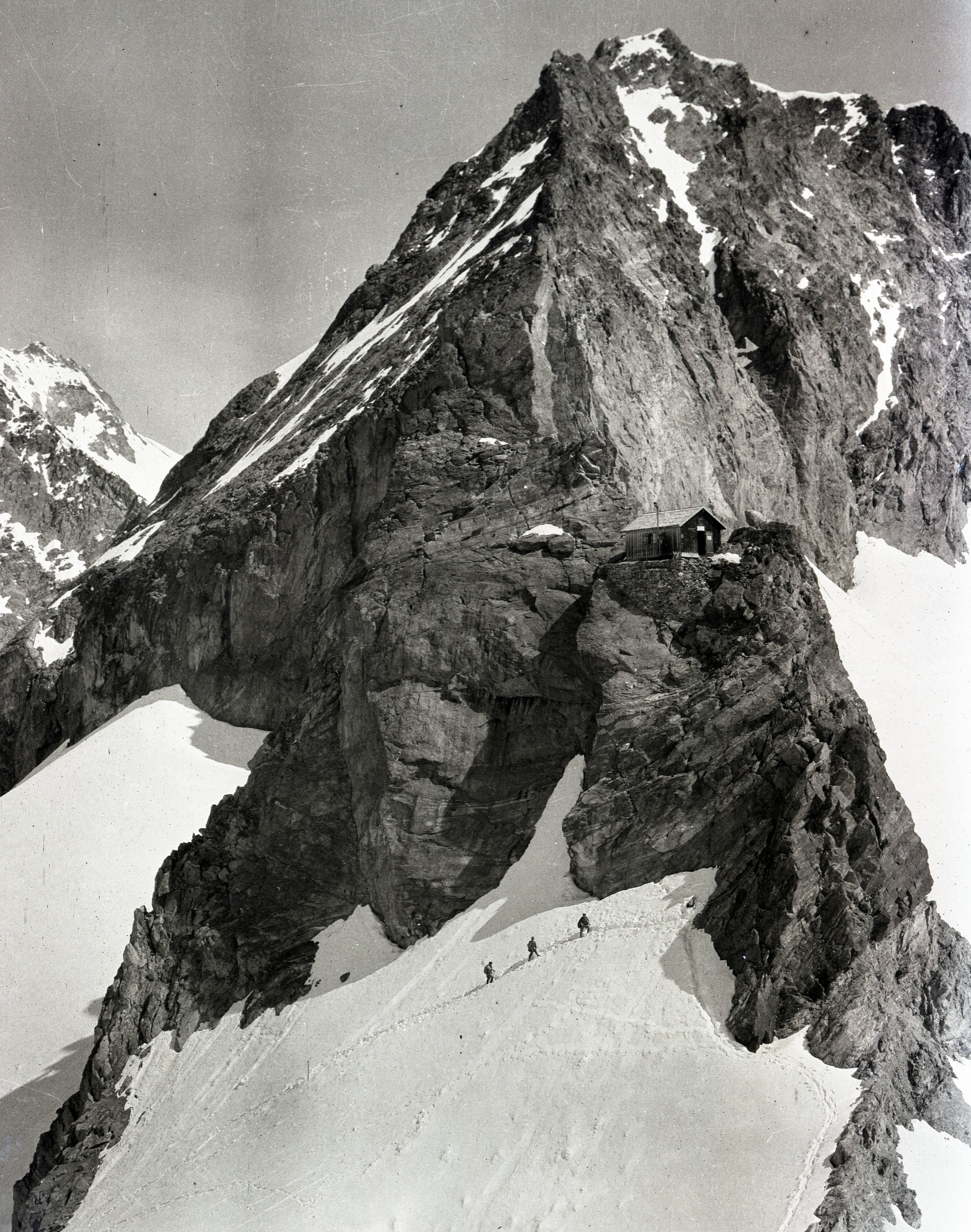

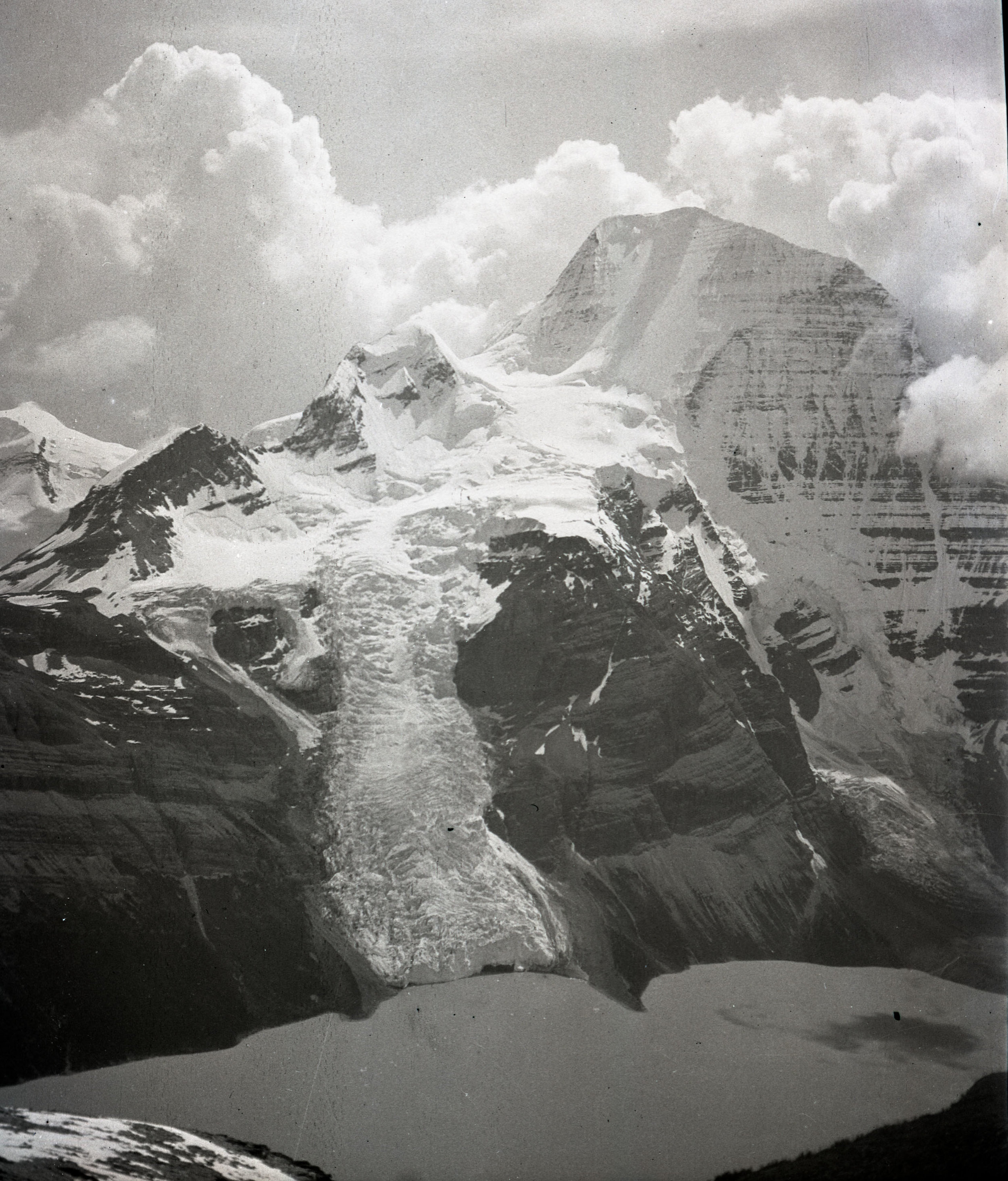

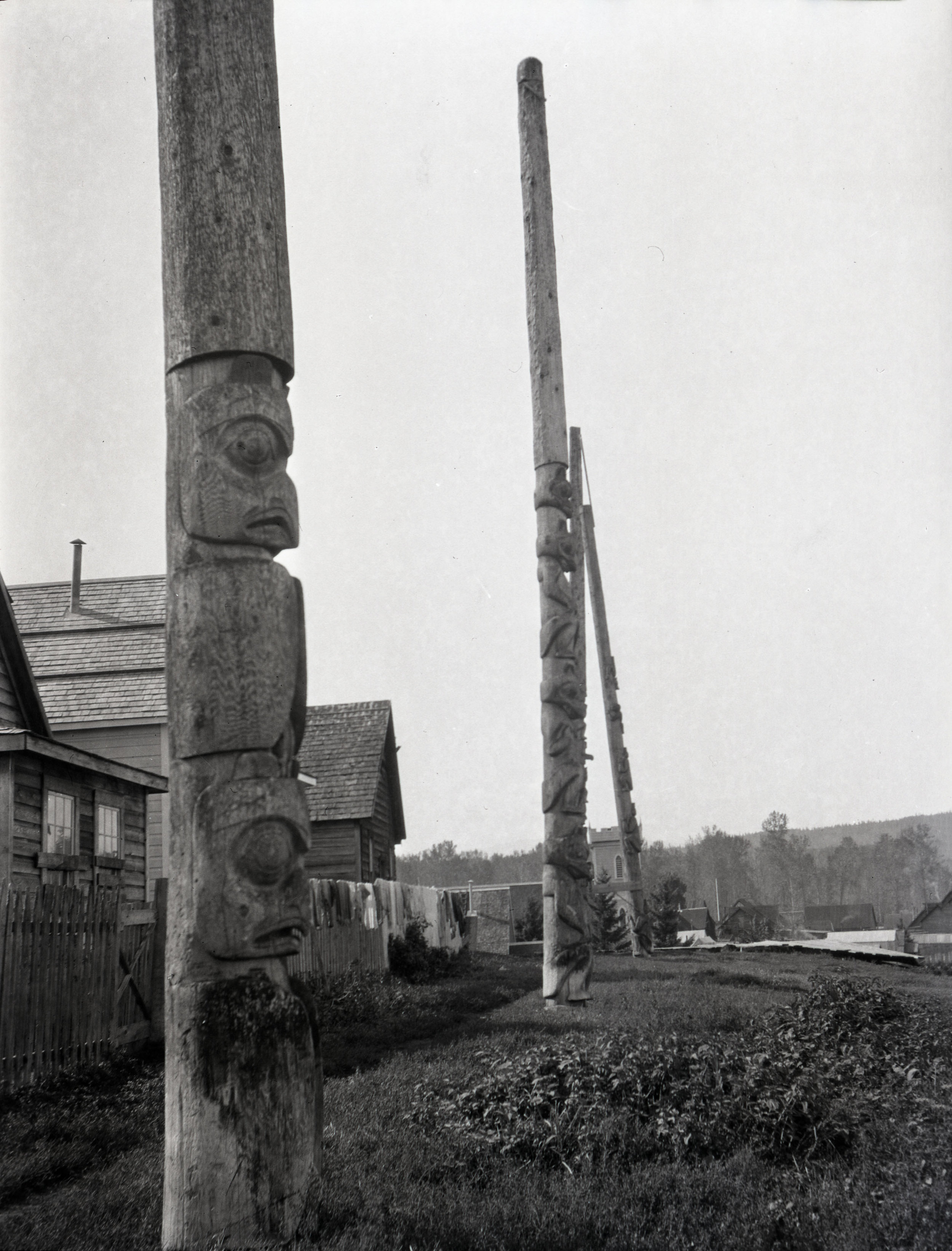

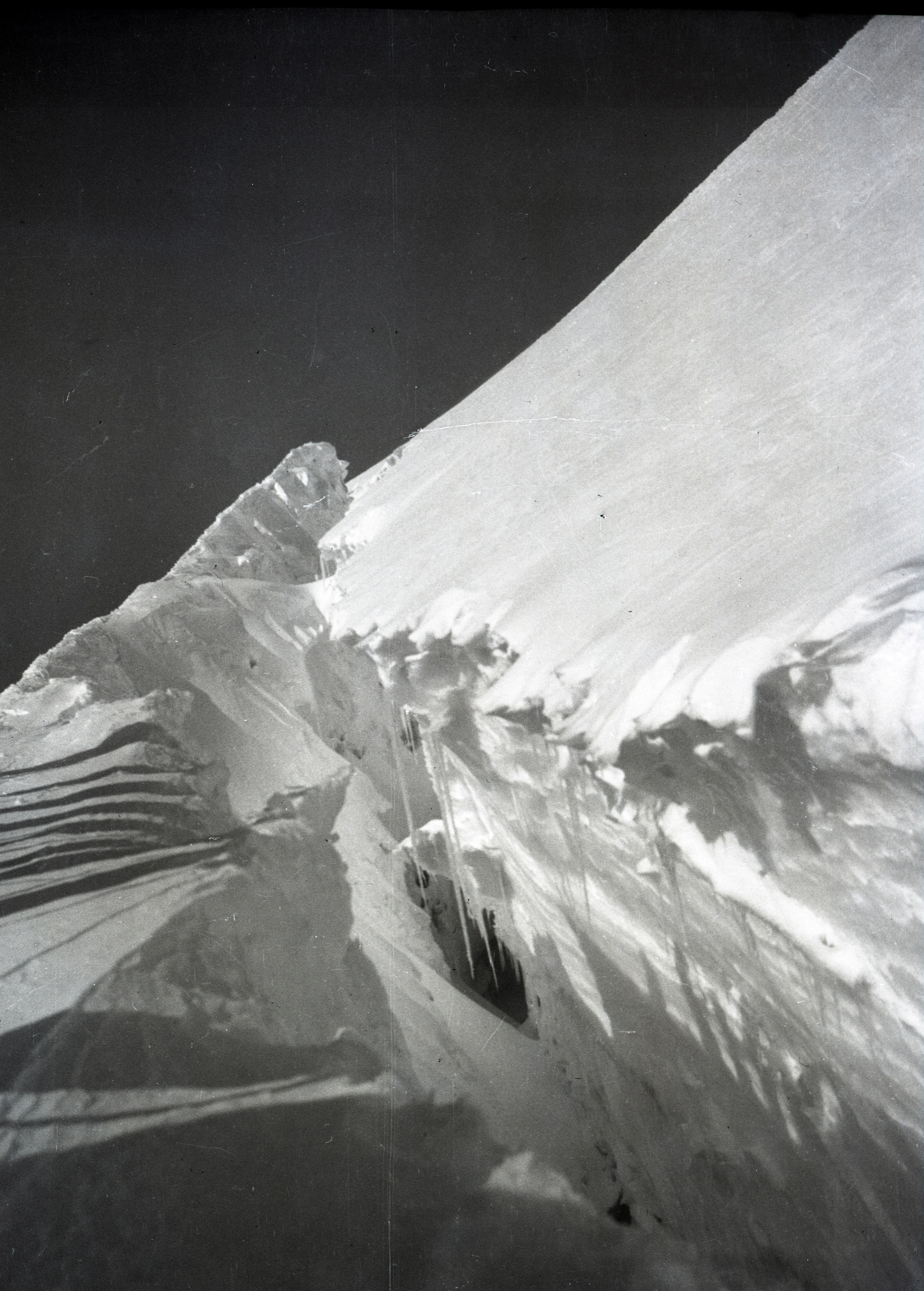

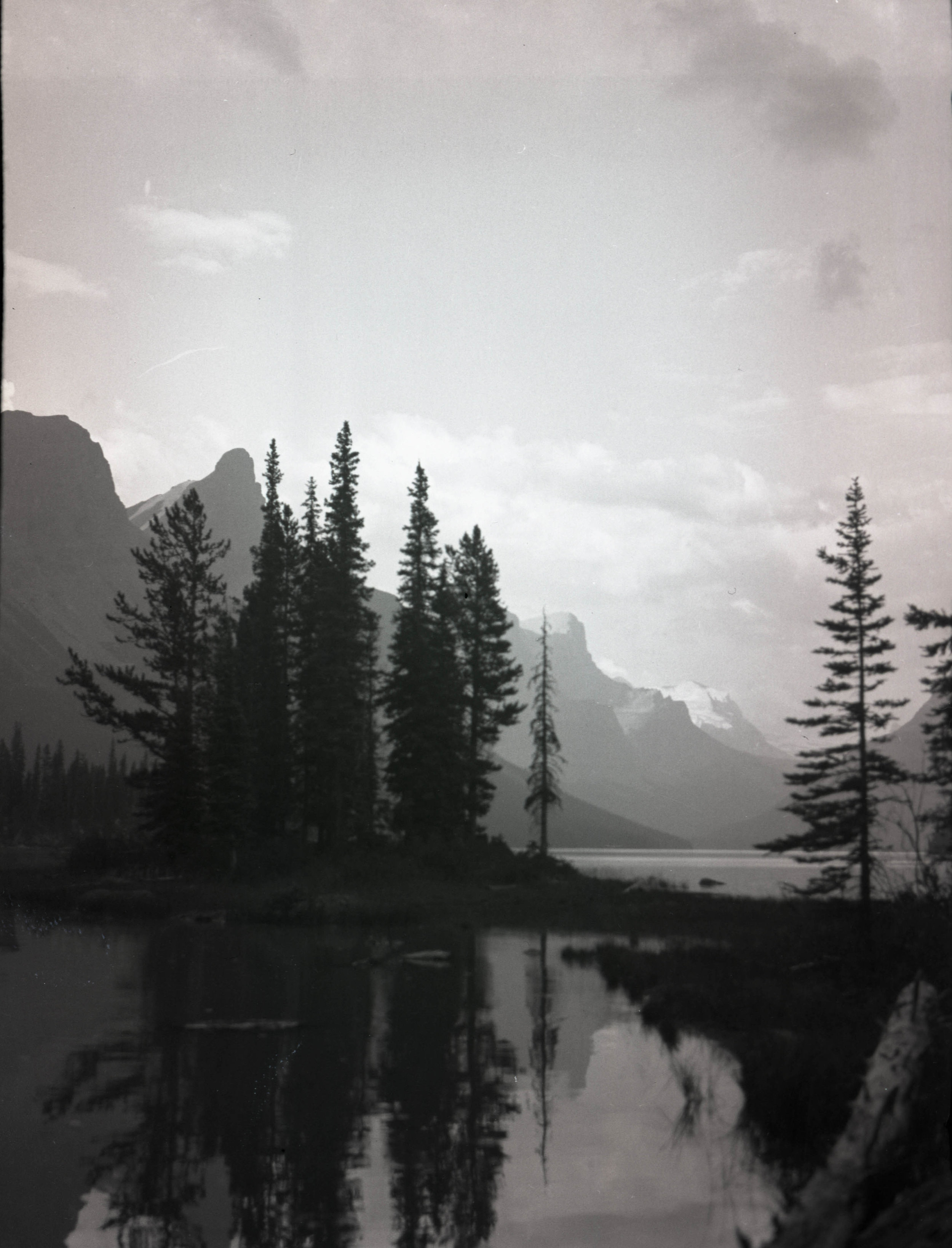

At the American Alpine Club Library, we’re very fortunate to have quite a few collections of photographs of climbing and mountaineering from the early 20th century. One of these, a collection of roughly 3000 photographic negatives dating from 1900 to about 1930, has been digitized in its entirety and made available to everyone.

It’s a great feeling to complete a project.

We’re excited to be able to increase access to this collection through digitization, which also reduces wear and tear on the original negatives and adds an additional layer of preservation.

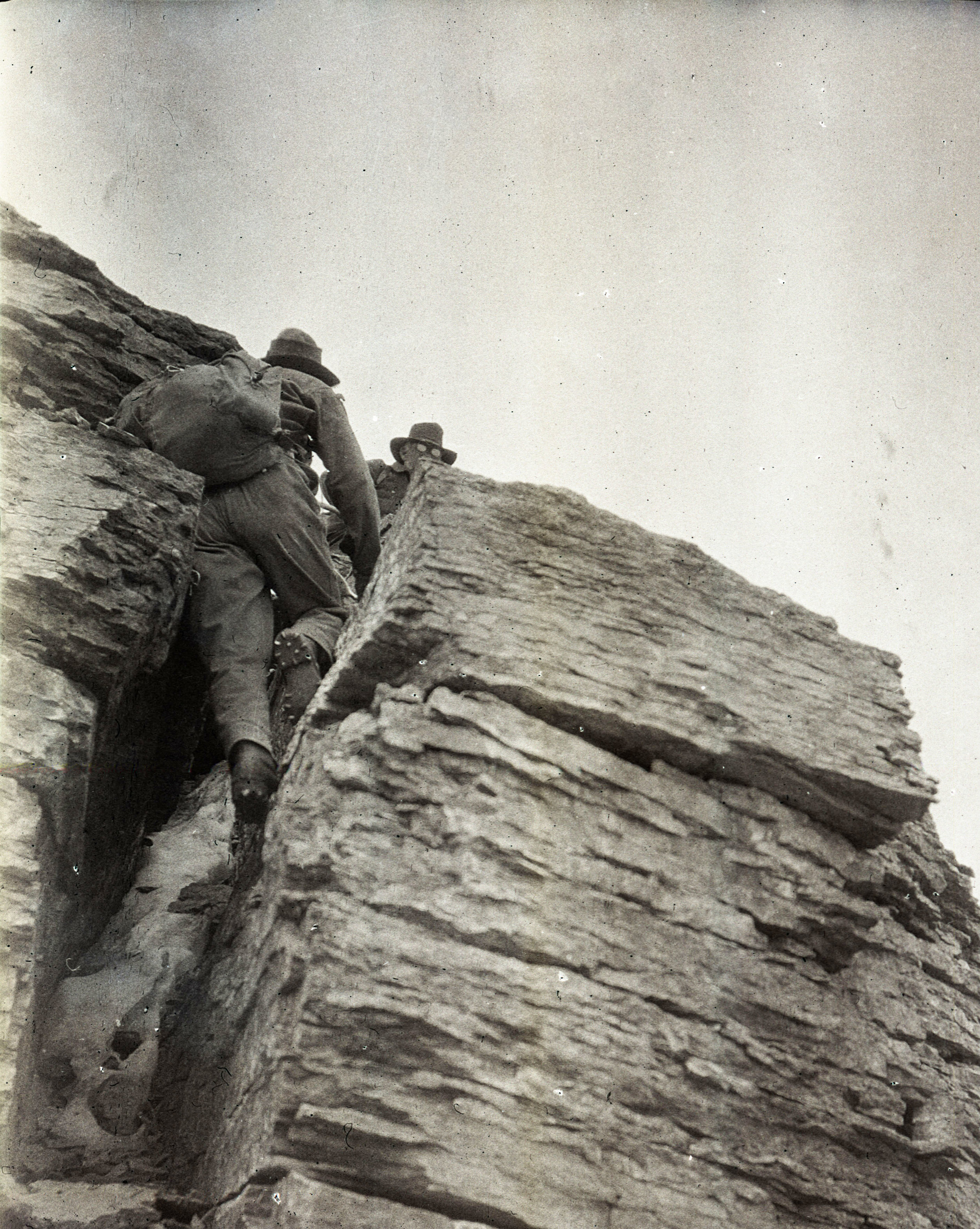

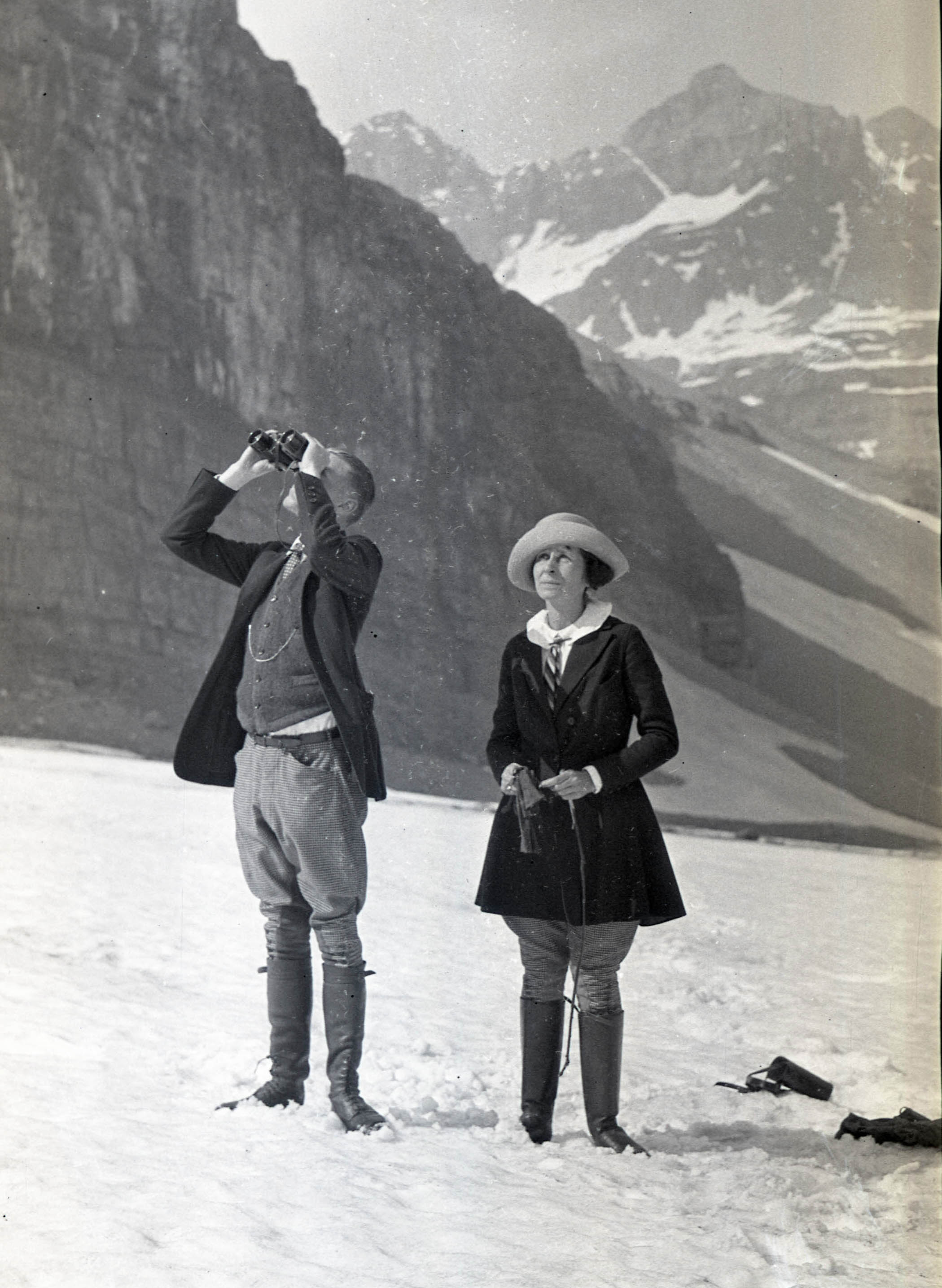

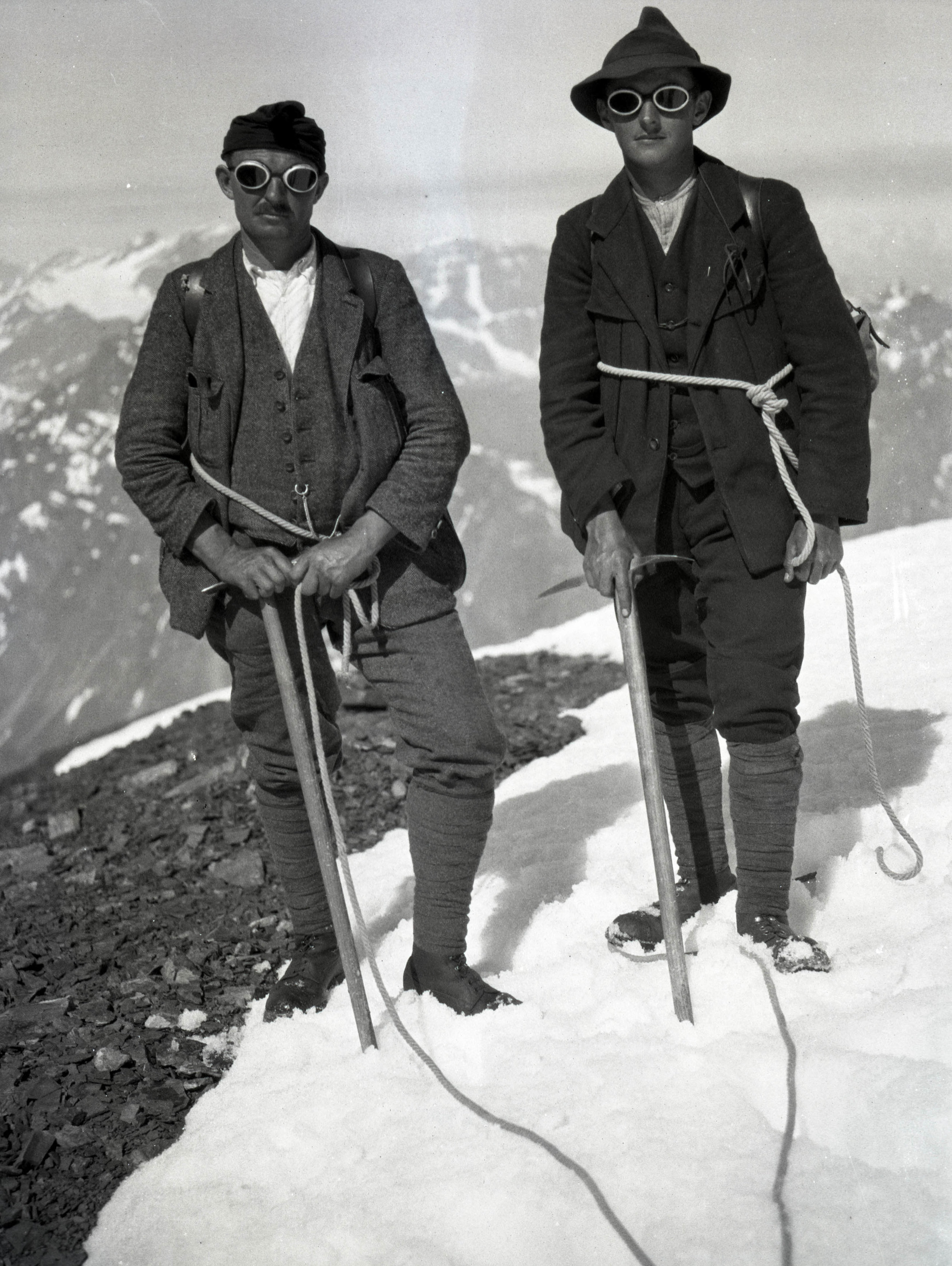

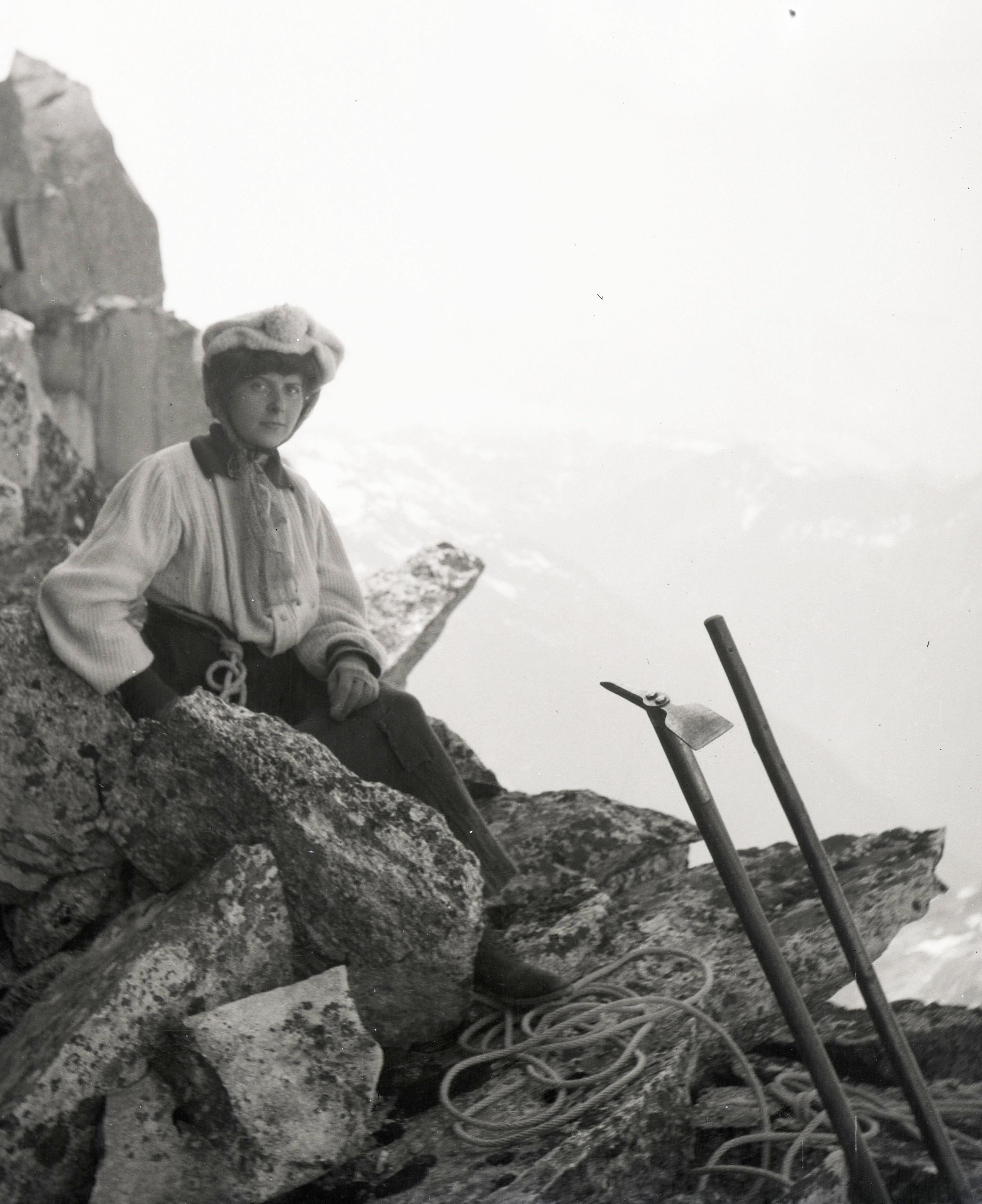

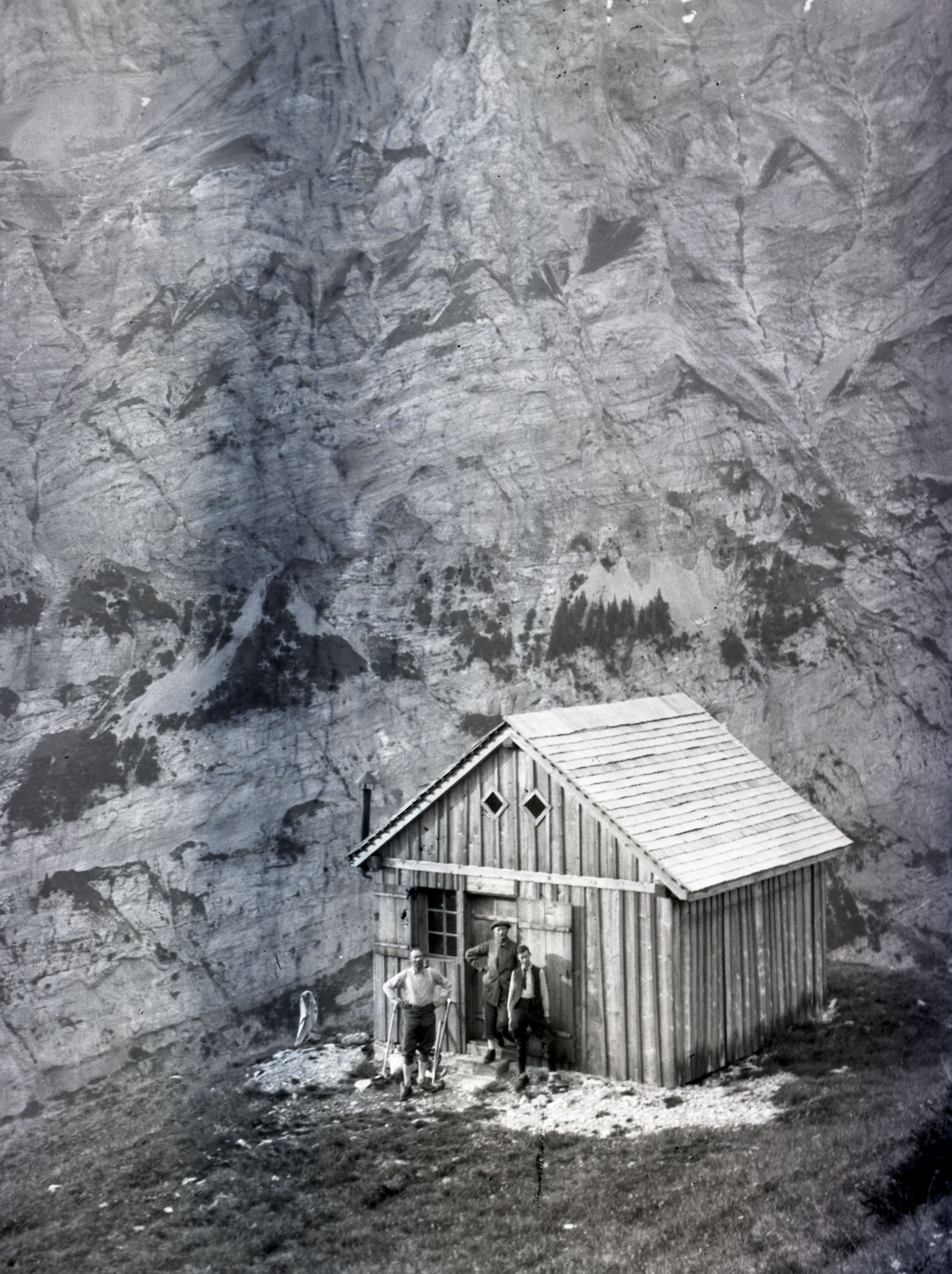

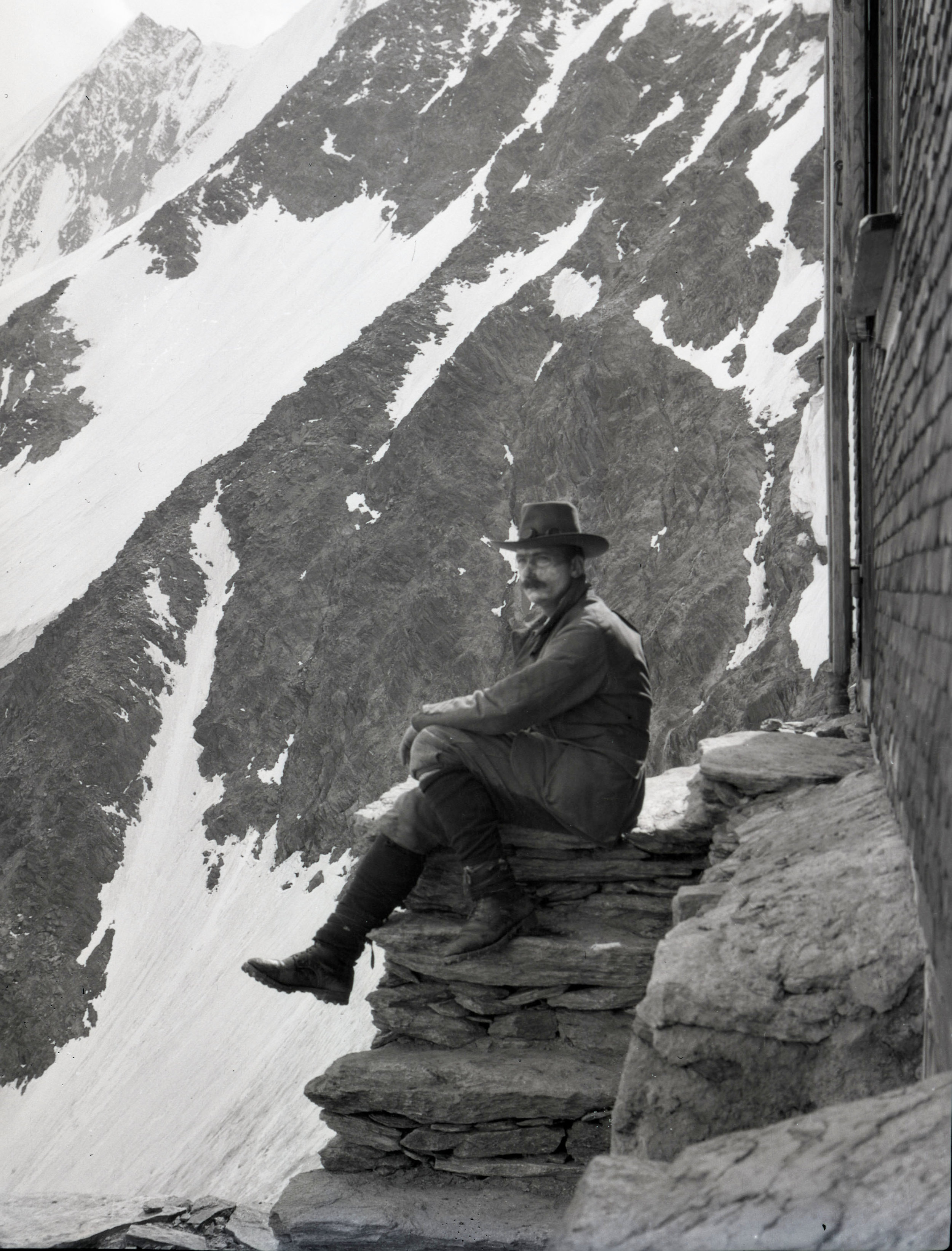

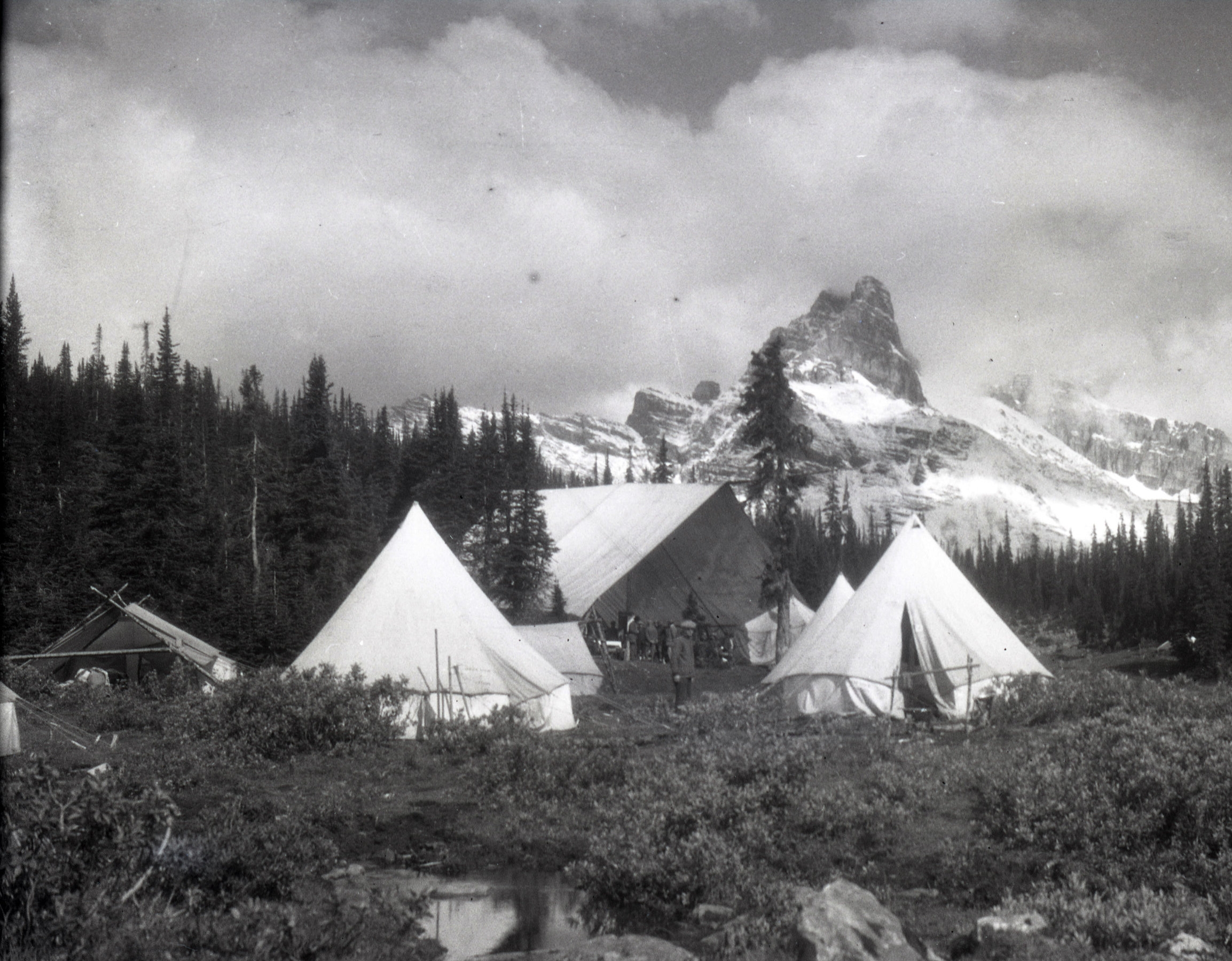

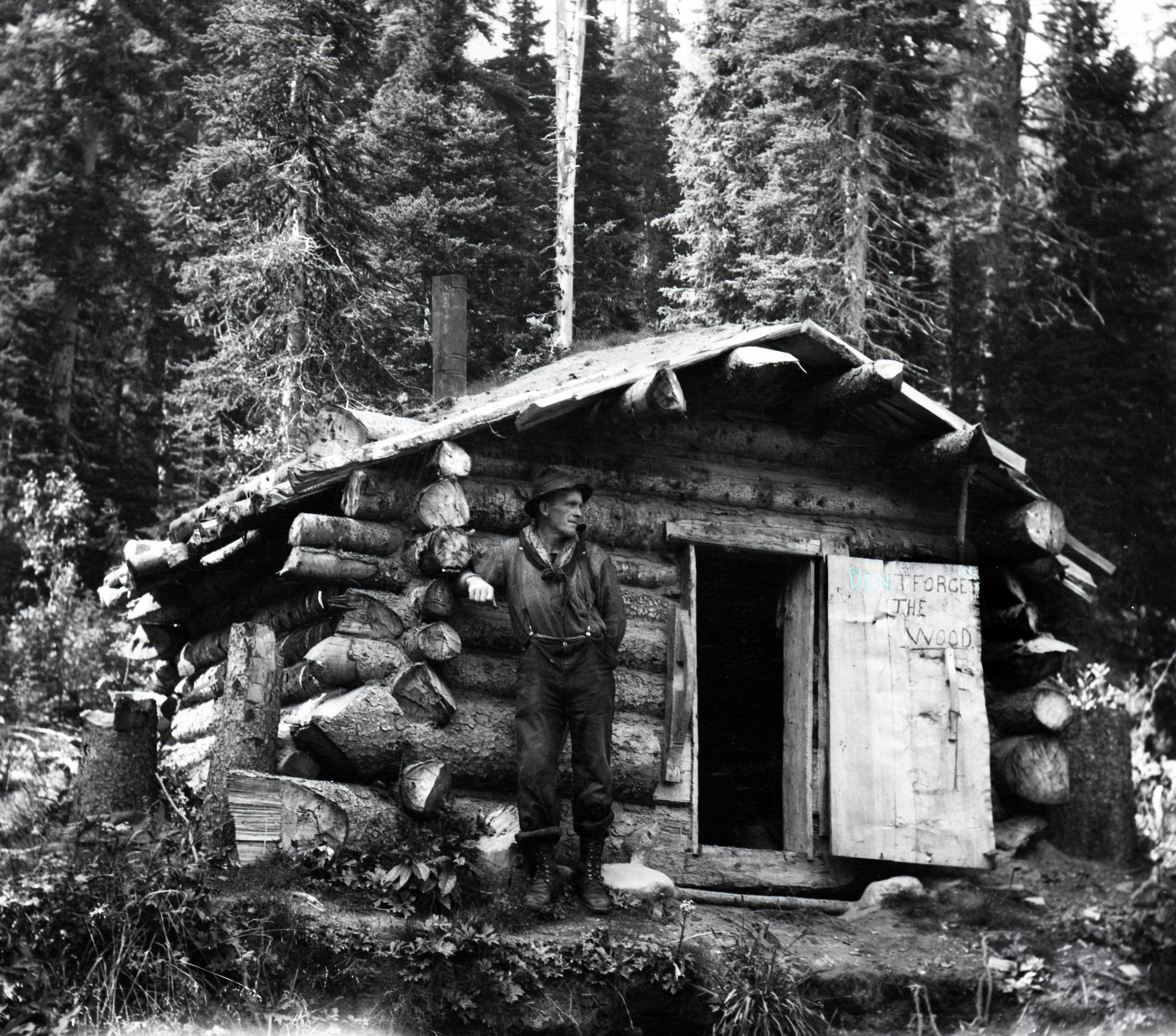

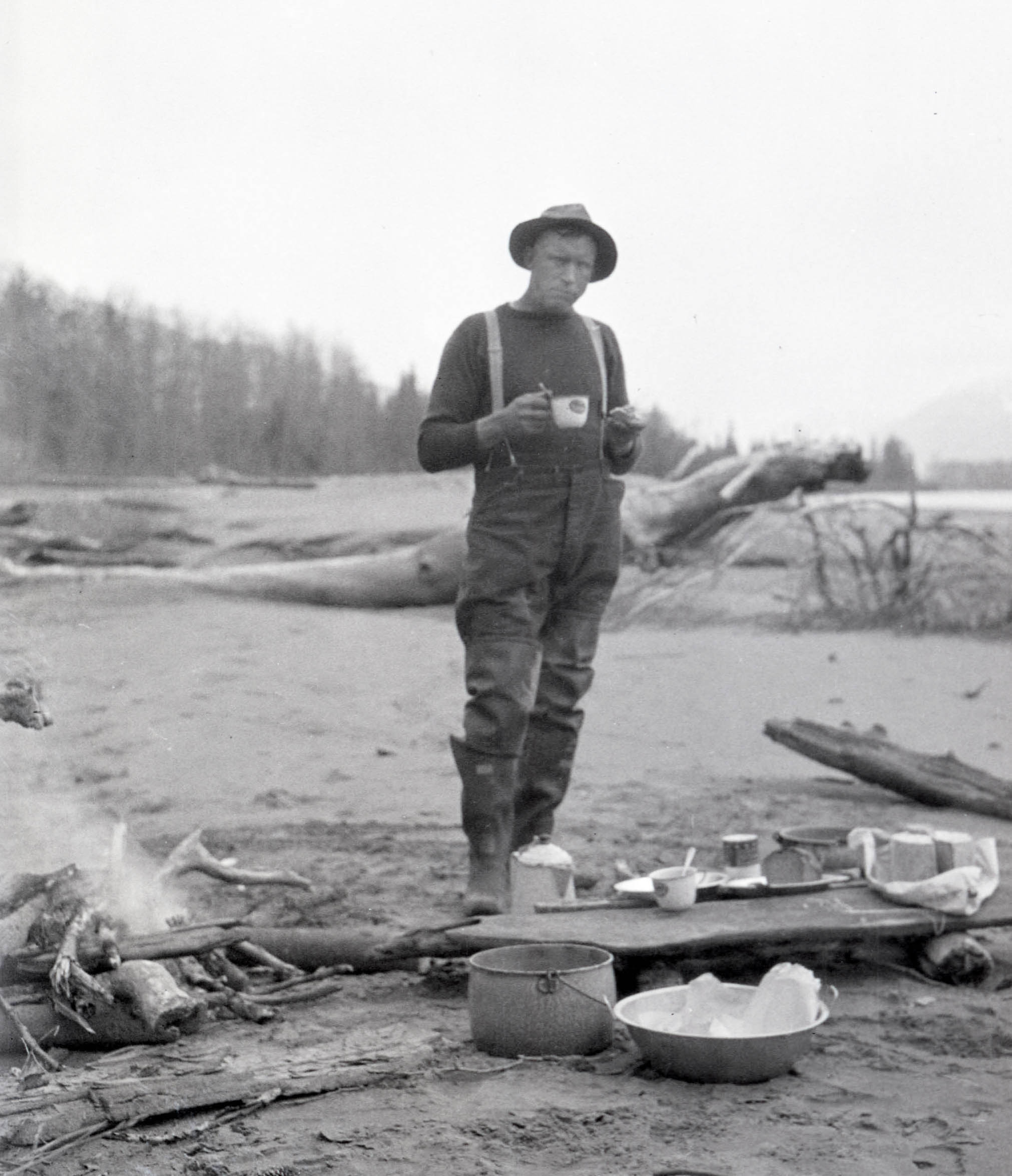

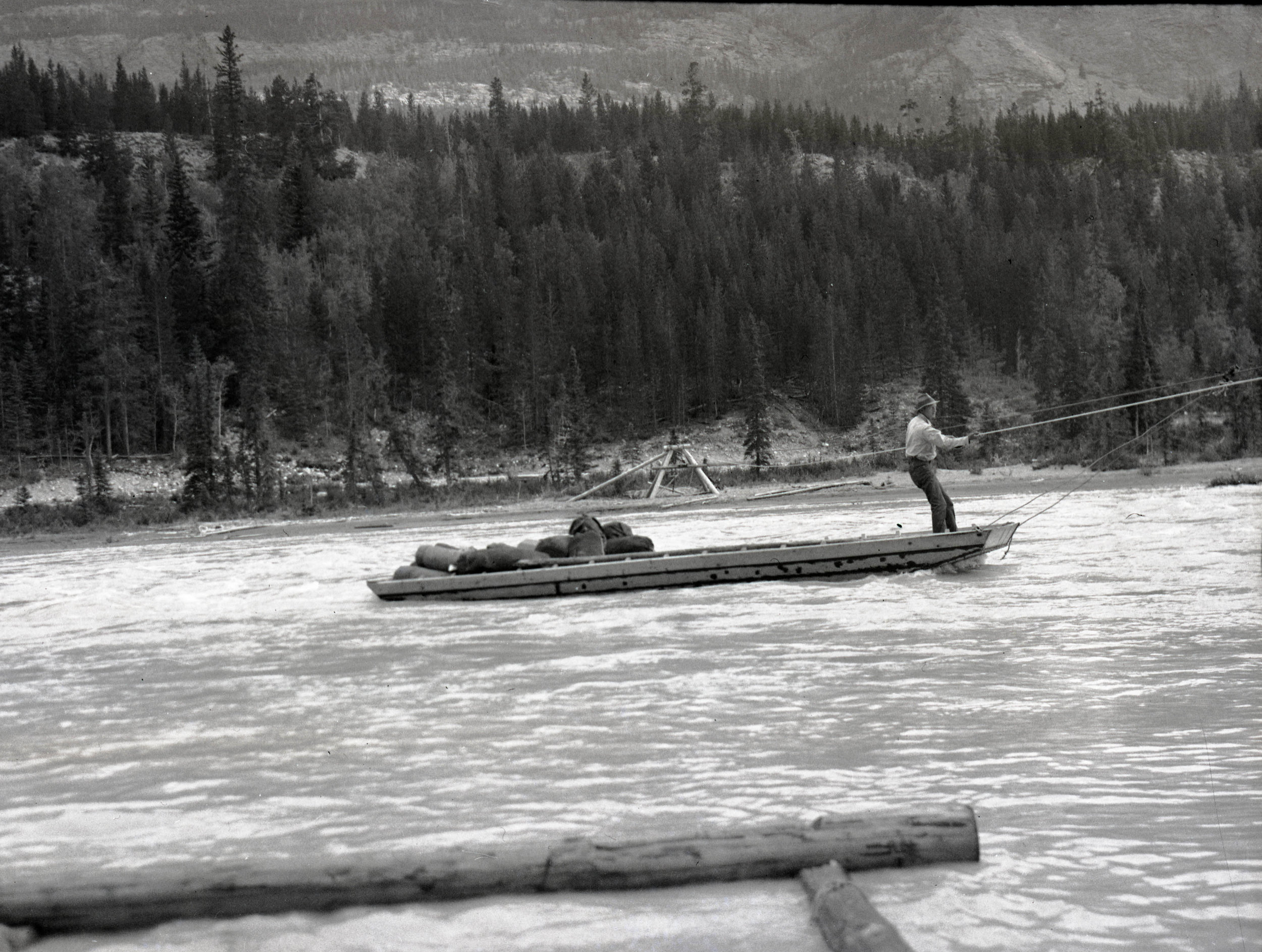

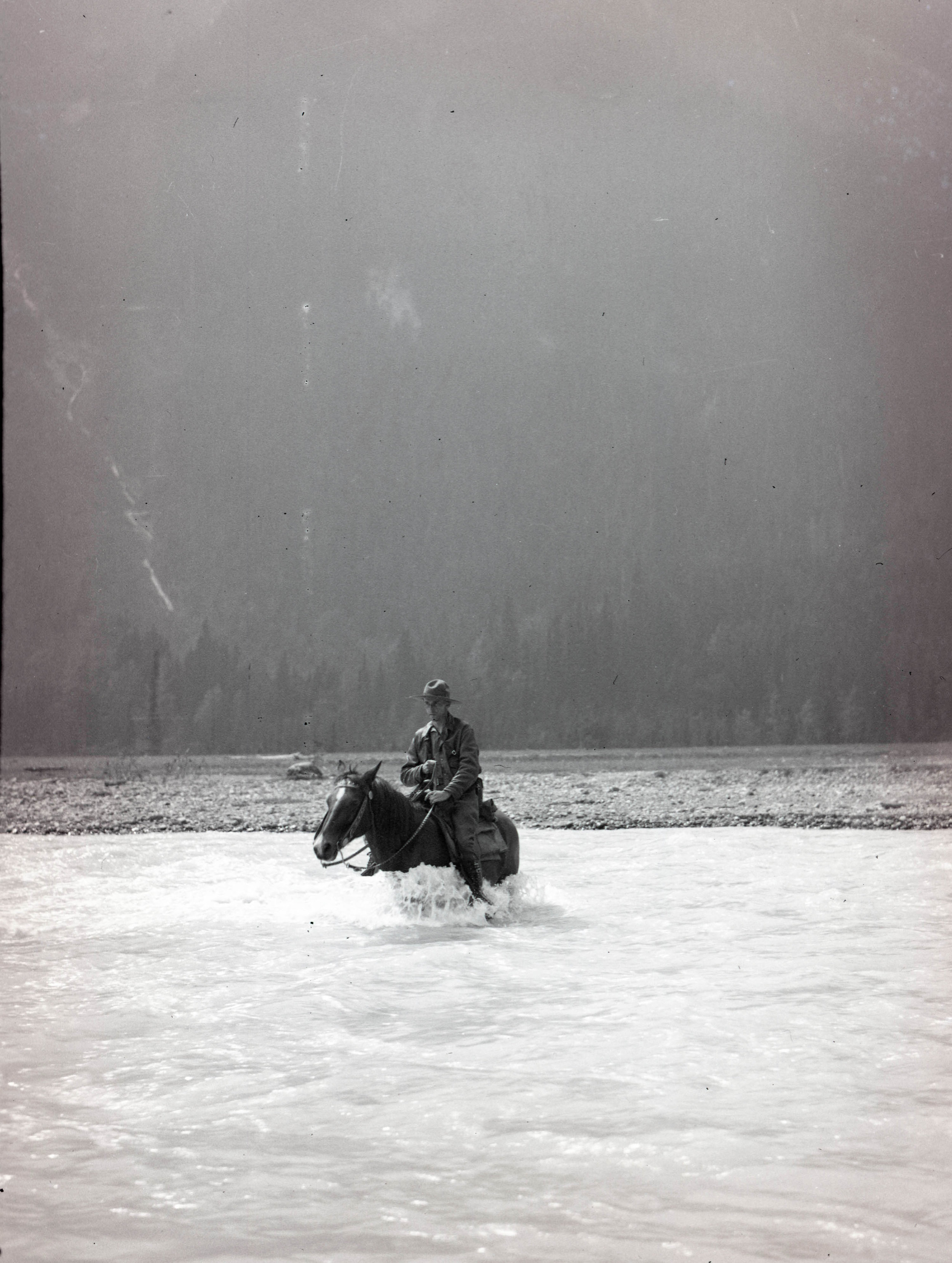

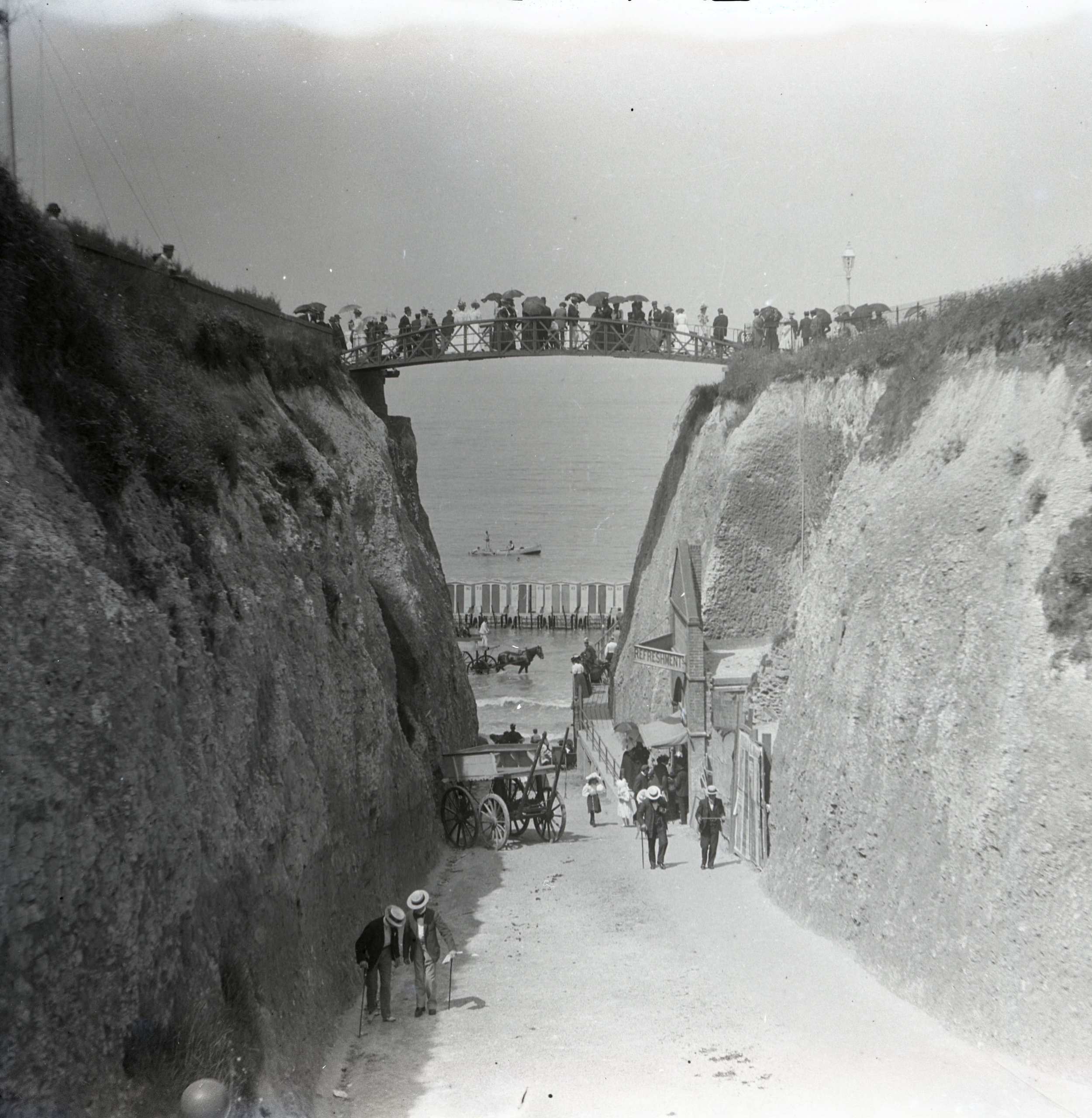

This collection of photos belonged to Andrew J. Gilmour, a dermatologist living and working in New York who was an avid climber and active member of the American Alpine Club during the 1920s and 1930s. He did a number of ascents in the Alps, the Canadian Rockies, the Cascades and the Western U.S., as well as Wales and the Lake District in the UK. His photos show us a lot about climbing at that time, the techniques, equipment, conditions and the people and places involved. It also provides us with a glimpse of what the world was like about 100 years ago.

We’ve gathered some of our favorite images from this collection in the slideshows below. Enjoy!

To see more of these images, check out our Andrew J. Gilmour album on Flickr.

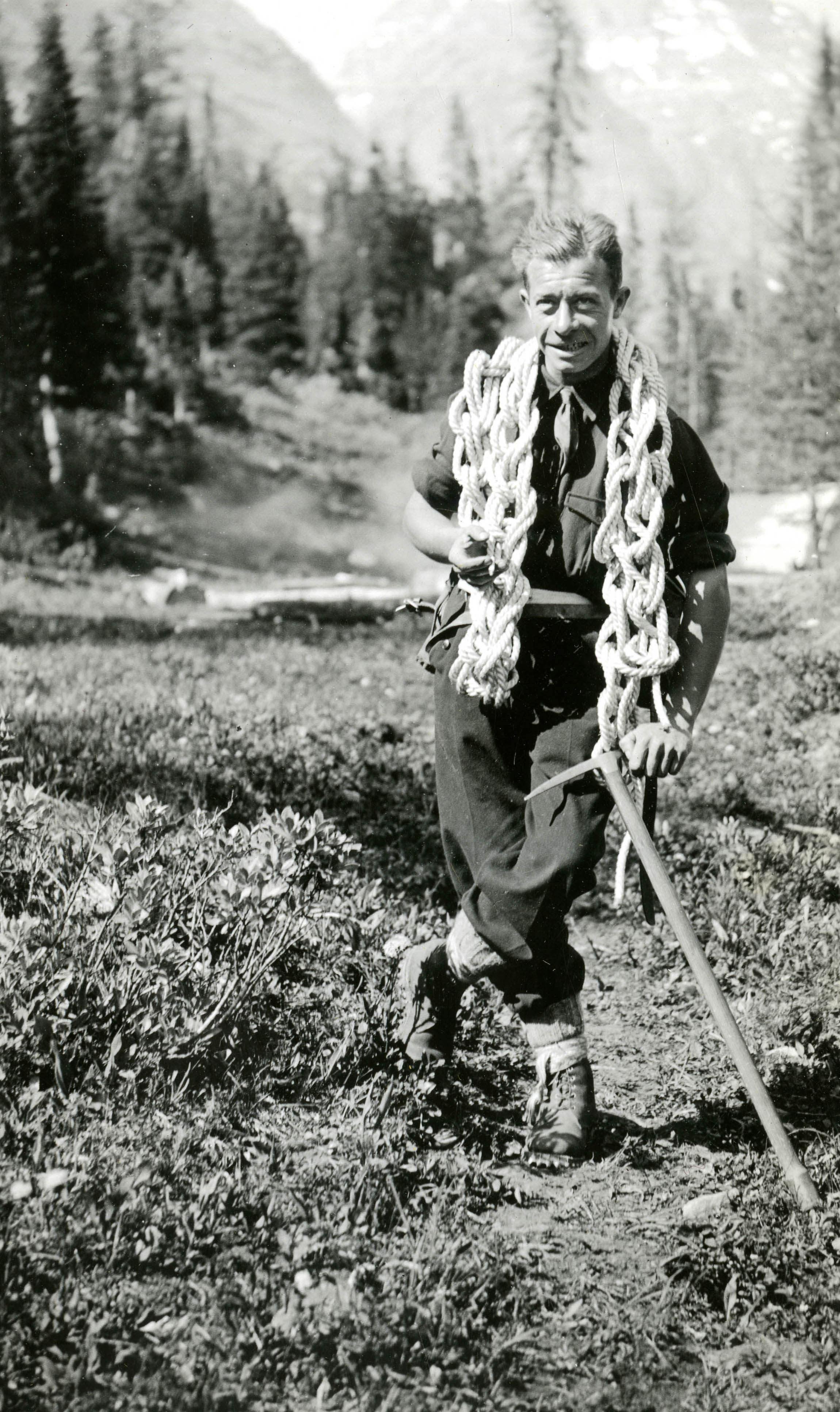

Climbing and Mountaineering

Photos of climbing parties and mountaineering expeditions from about 1910 to the mid 1930’s.

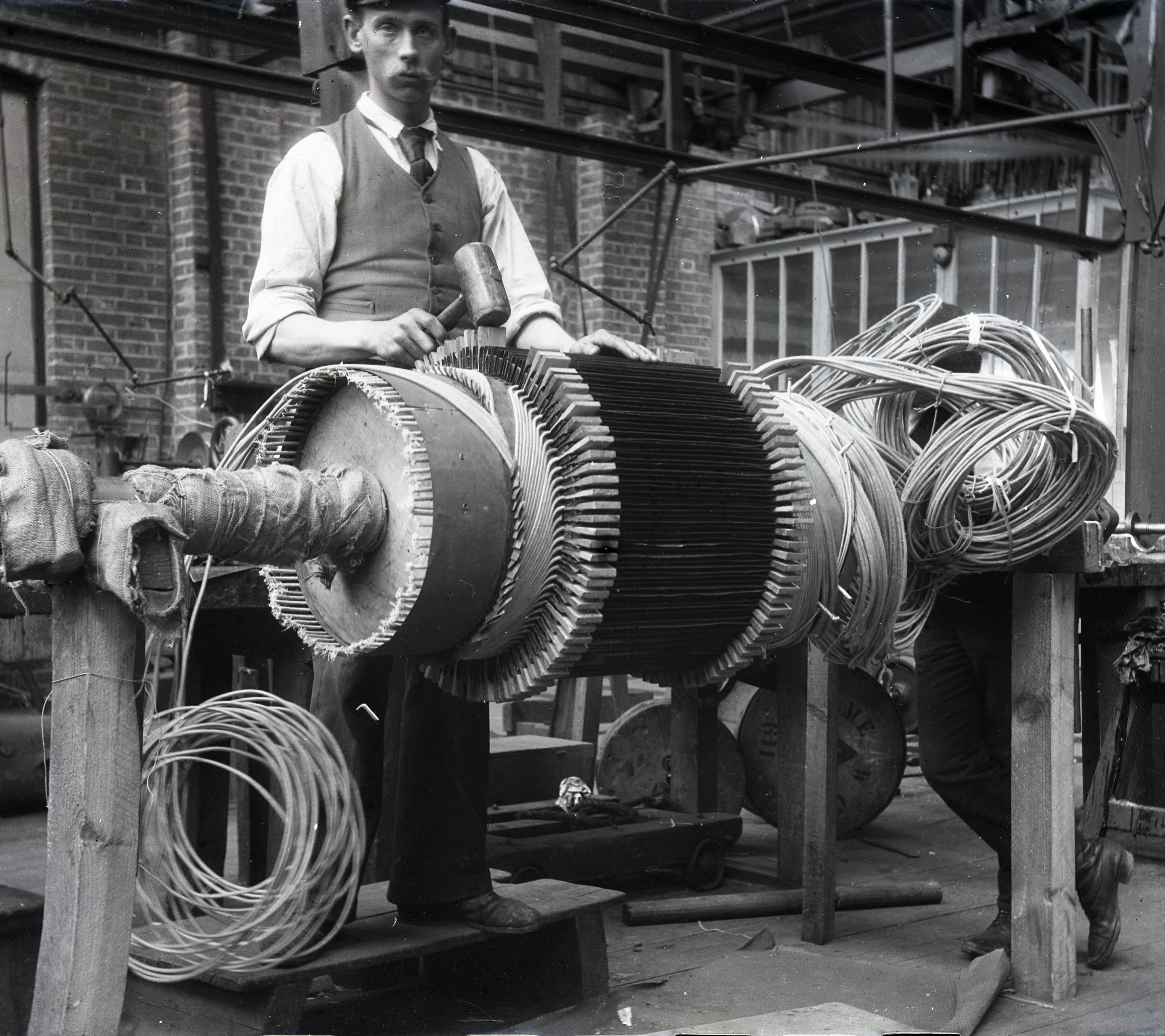

Equipment

Hobnail boots, hemp rope, canvas and silk tents and men’s and women’s climbing attire.

Summits

Men and women on top

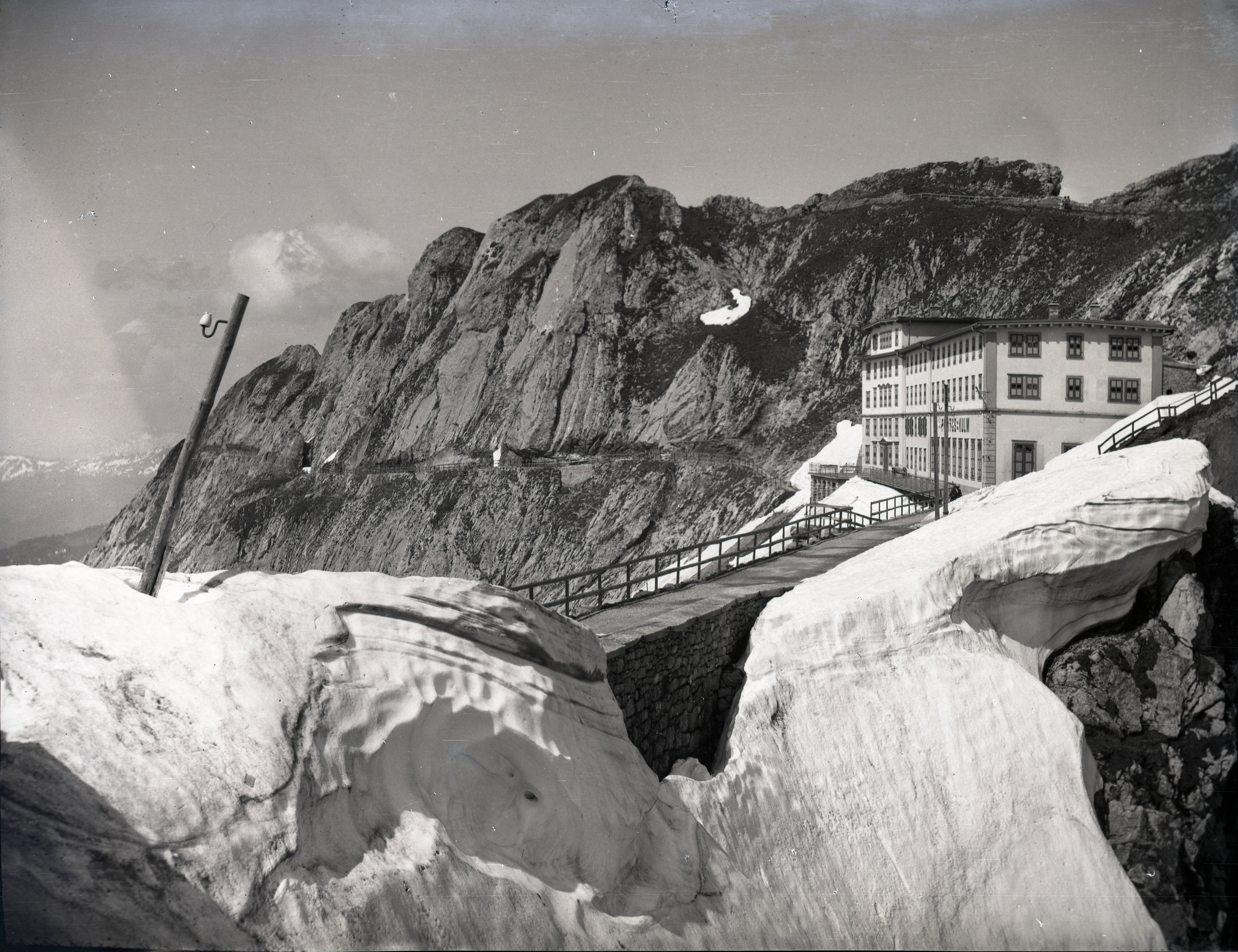

Camps and Huts

Huge camps for gatherings with the Alpine Club of Canada, tents and lean-tos in the woods, Swiss Alpine Club huts - many of which are still in use today.

Travel

It was harder in those days to get to some of these remote locations. There were far fewer roads, almost no highways and air travel was still in its infancy. Trains, ships and horses were commonly used.

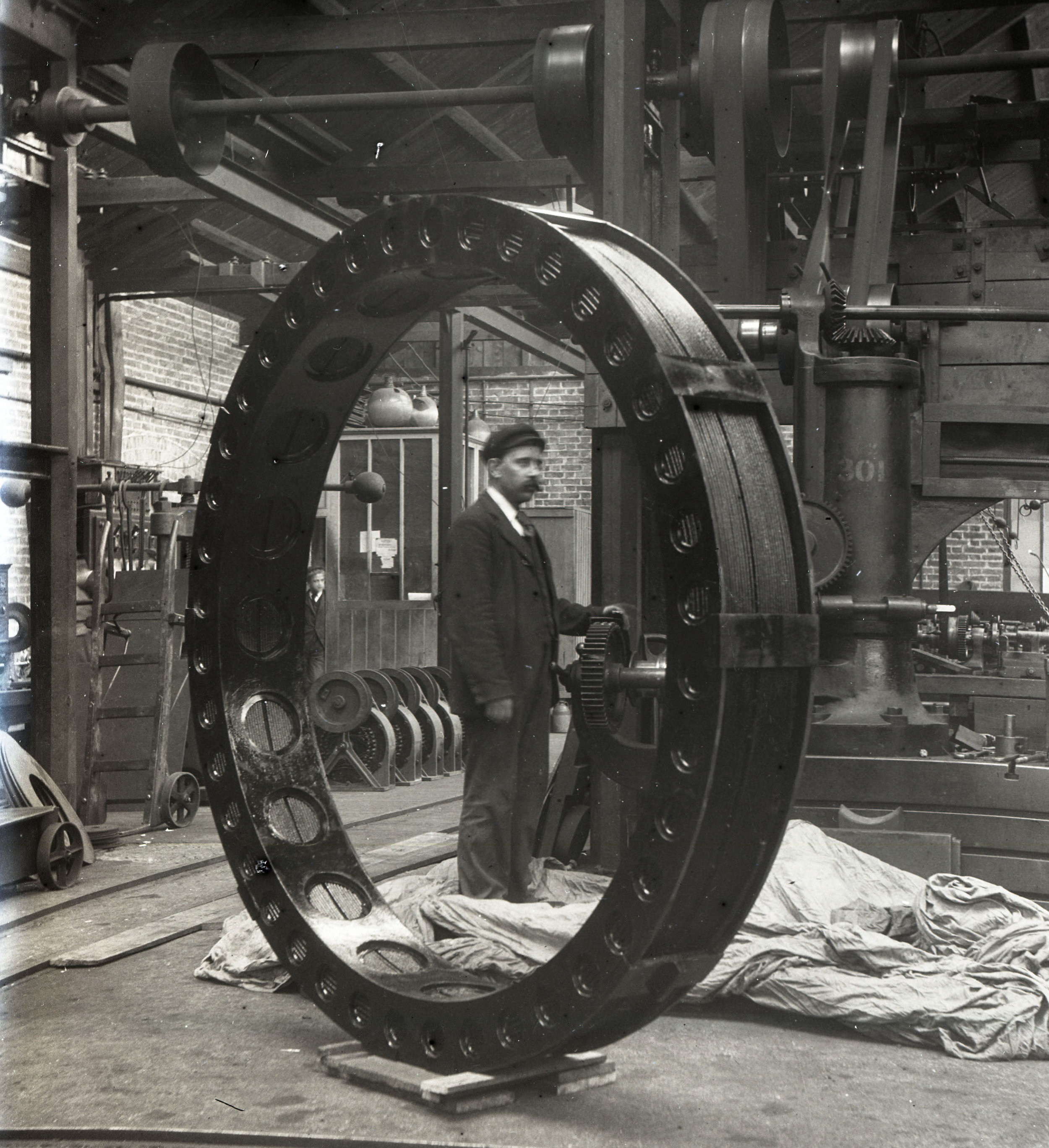

Life and Times

The world has changed a lot since 1900 - these photos illustrate just a few of the differences.

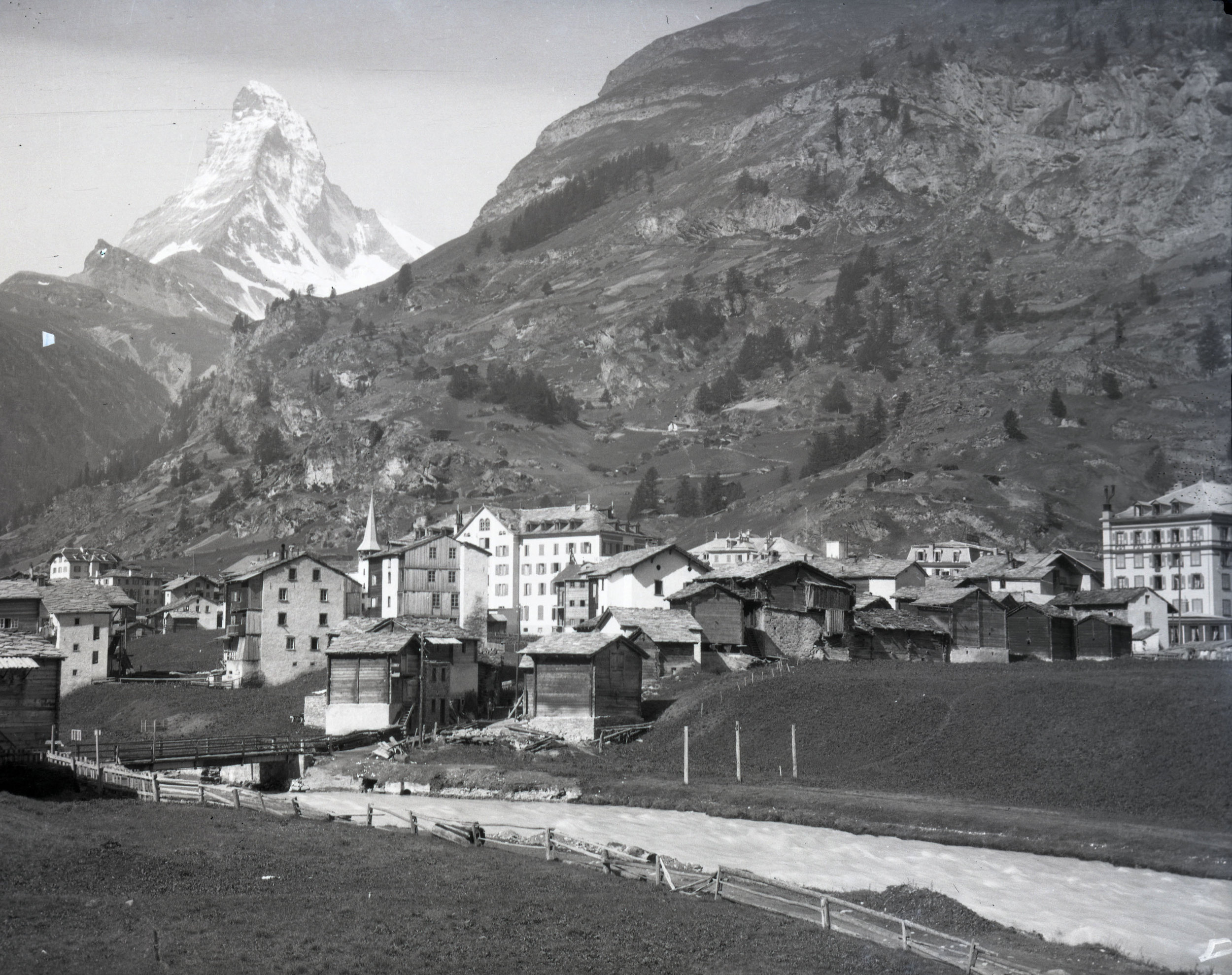

Places

Some gorgeous photos of some famous locations as they used to be.

Check out our Flickr account for more! Or, to view all the photos, head to our archival collections site and scroll down to Collection Tree.

Suggested reading:

For details of mountaineering and climbing in the first decades of the 20th century, check out the handbook Mountain Craft by Geoffrey Winthrop Young.

For more about some of the places depicted in these photos:

Mount Rainier a Climbing Guide by Mike Gauthier

Cascades Rock the 160 Best Multipitch Climbs of all Grades by Blake Herrington

The North Cascades by William Dietrich

Mont Blanc the Finest Routes: rock, snow, ice and mixed by Philippe Batoux

Mont Blanc: 5 routes to the summit by Franȯis Damilano

Swiss Rock Granite Bregaglia: a selected rock climbing guide by Chris Mellor

Canadian Rock select climbs of the west by Kevin McLane

Sport climbs in the Canadian Rockies by John Marin and Jon Jones

Mixed Climbs in the Canadian Rockies by Sean Isaac

For more information about the person who took these photos, you can read Gilmour’s obituary in the American Alpine Journal.

Beasts of Burden

The Colorado Mountains: View from the Archives

Atop Mount Audubon, circa 1916-18.

Now more accessible than ever! Thanks to a grant from the Colorado Historical Records Advisory Board, we were able to process and digitize a portion of the Colorado Mountain Club Archives.

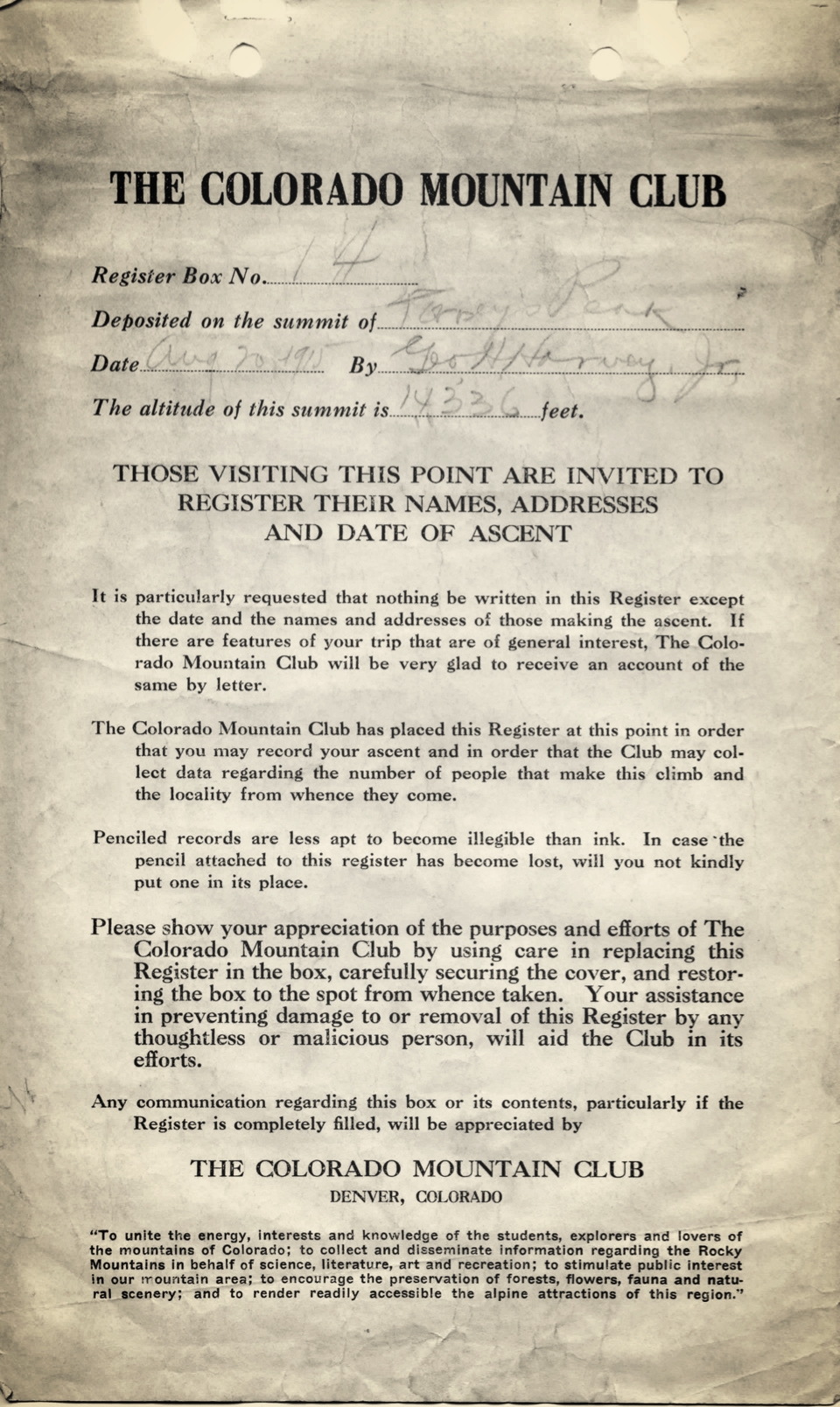

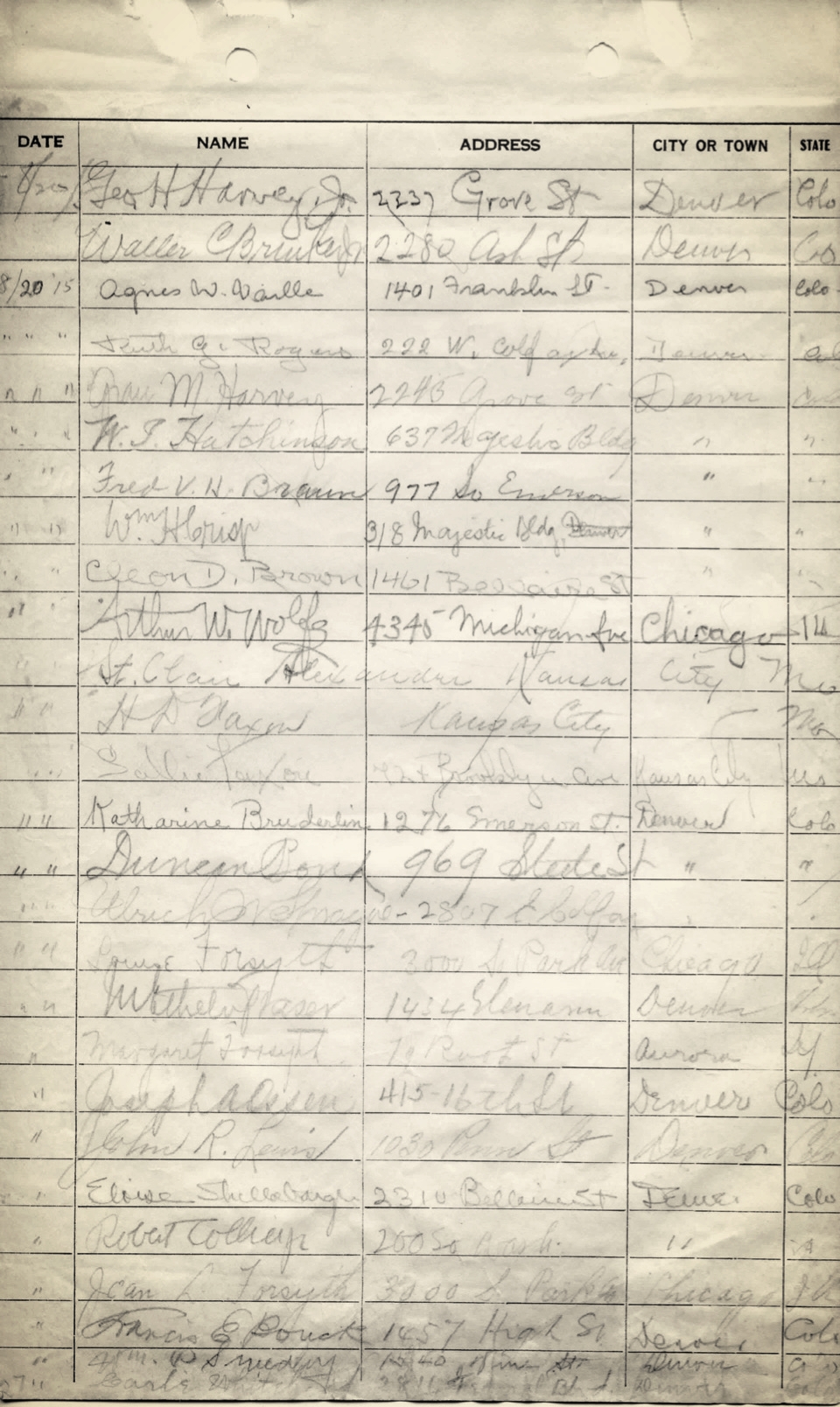

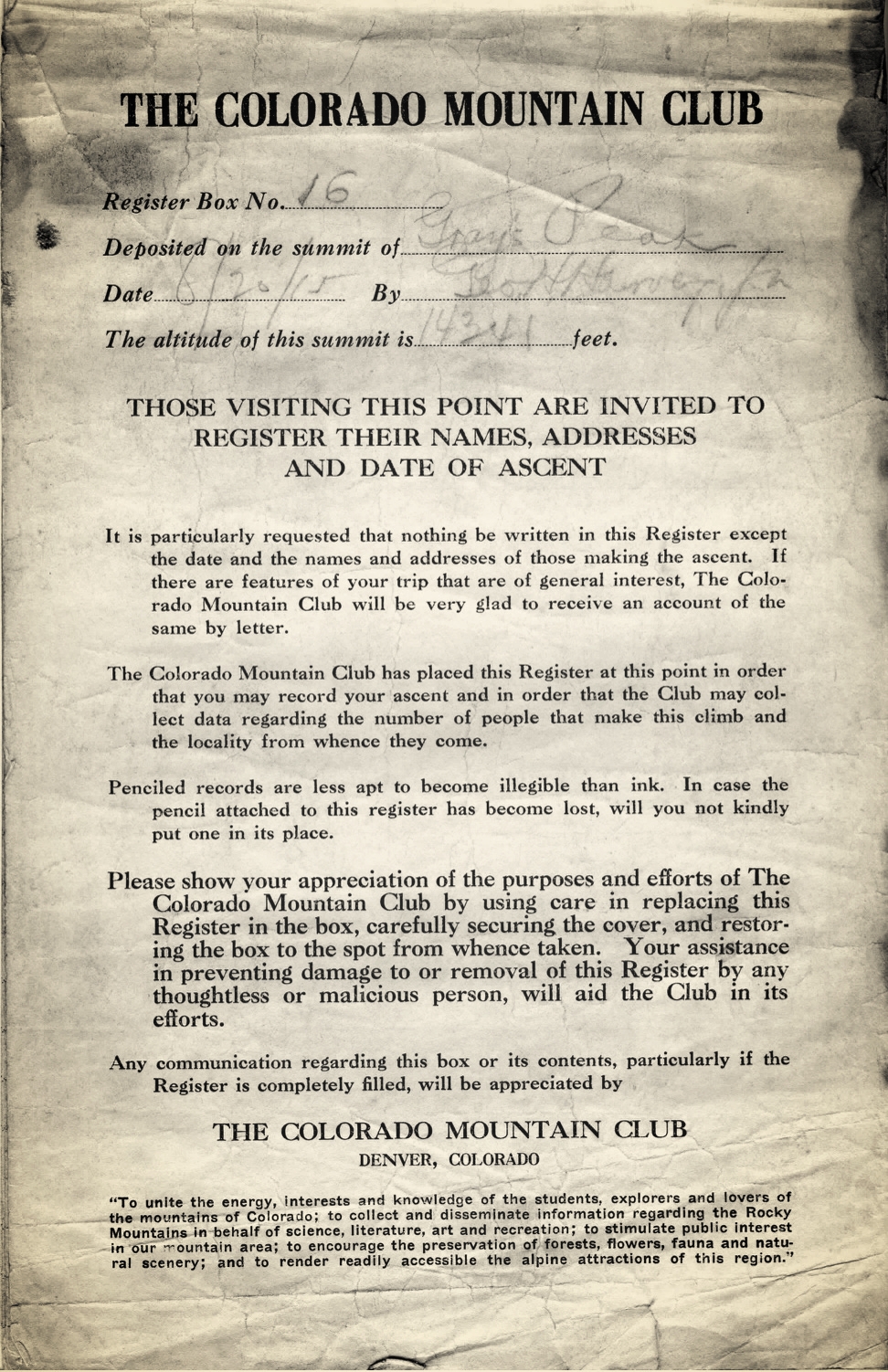

Located in the American Mountaineering Center, the Colorado Mountain Club (CMC) Archives are maintained by the staff of the American Alpine Club (AAC) Library. From April 2017 to May 2018, with a dedicated group of enthusiastic CMC & AAC volunteers, we organized, inventoried, rehoused, and digitized much of this collection. The most painful part was organizing the huge duplicate collection of Trail & Timberline back issues and flattening summit registers. Interested in purchasing back issues of the T&T? Contact us at [email protected]. Proceeds will go towards archives maintenance.

What's in the Colorado Mountain Club Archives?

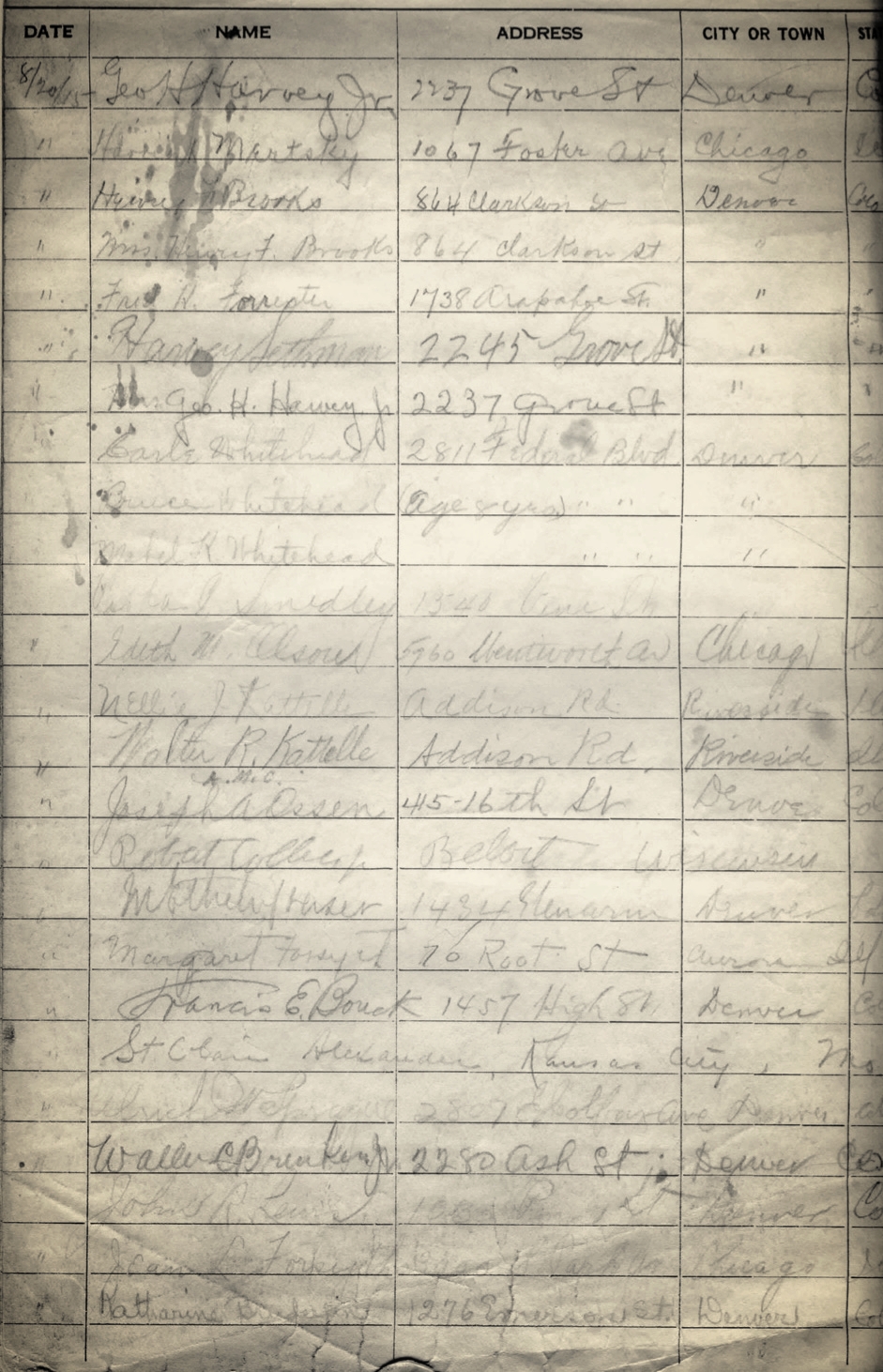

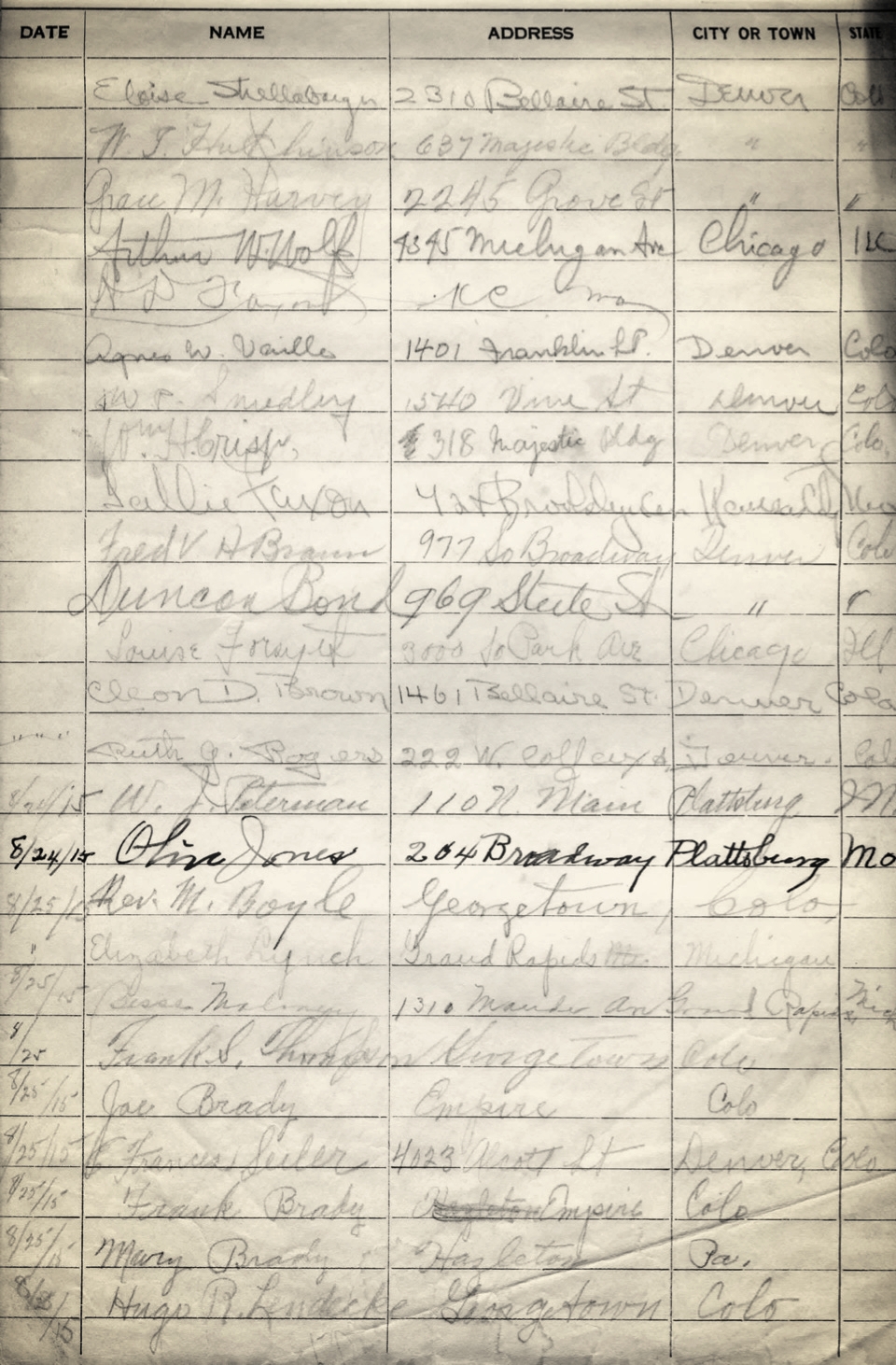

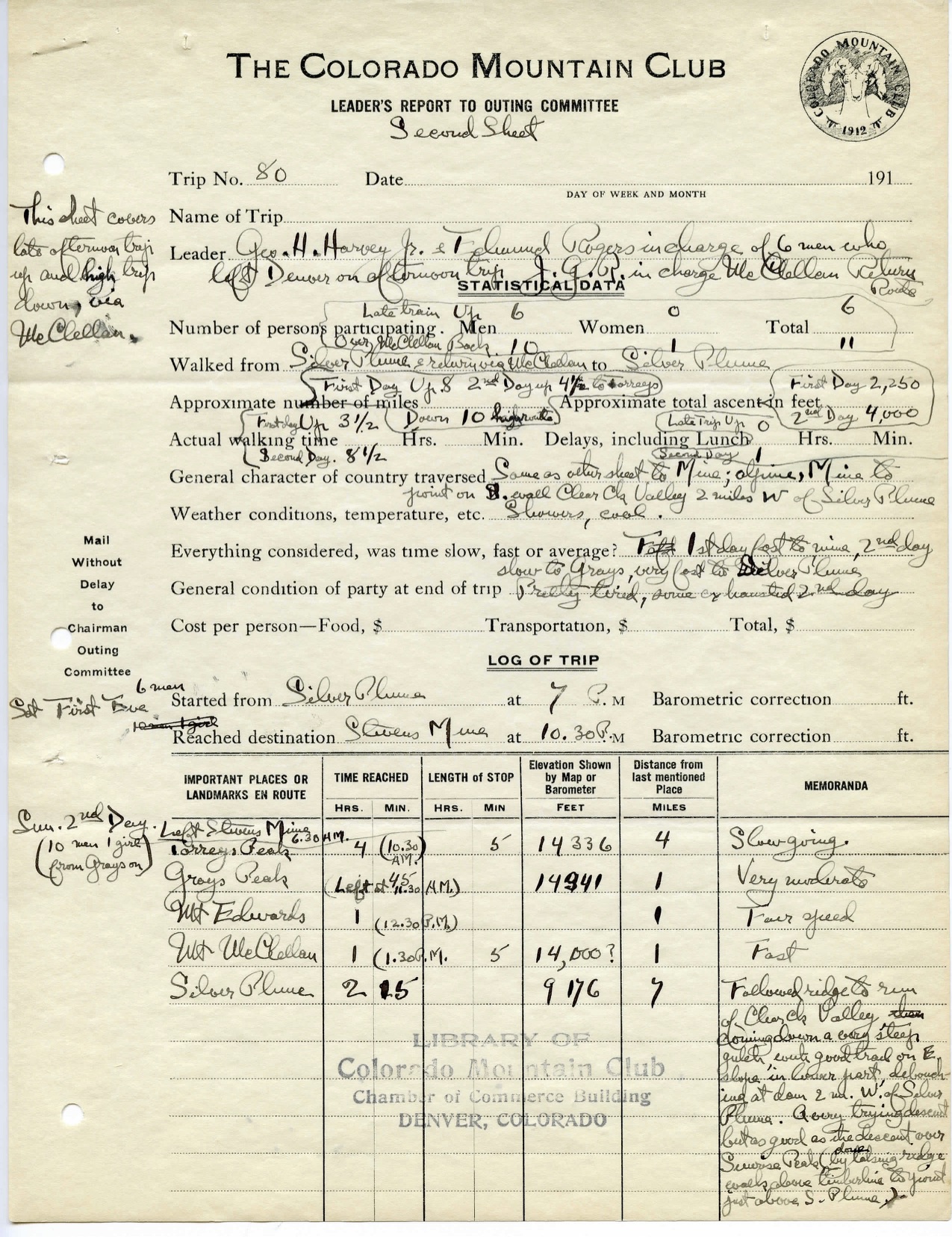

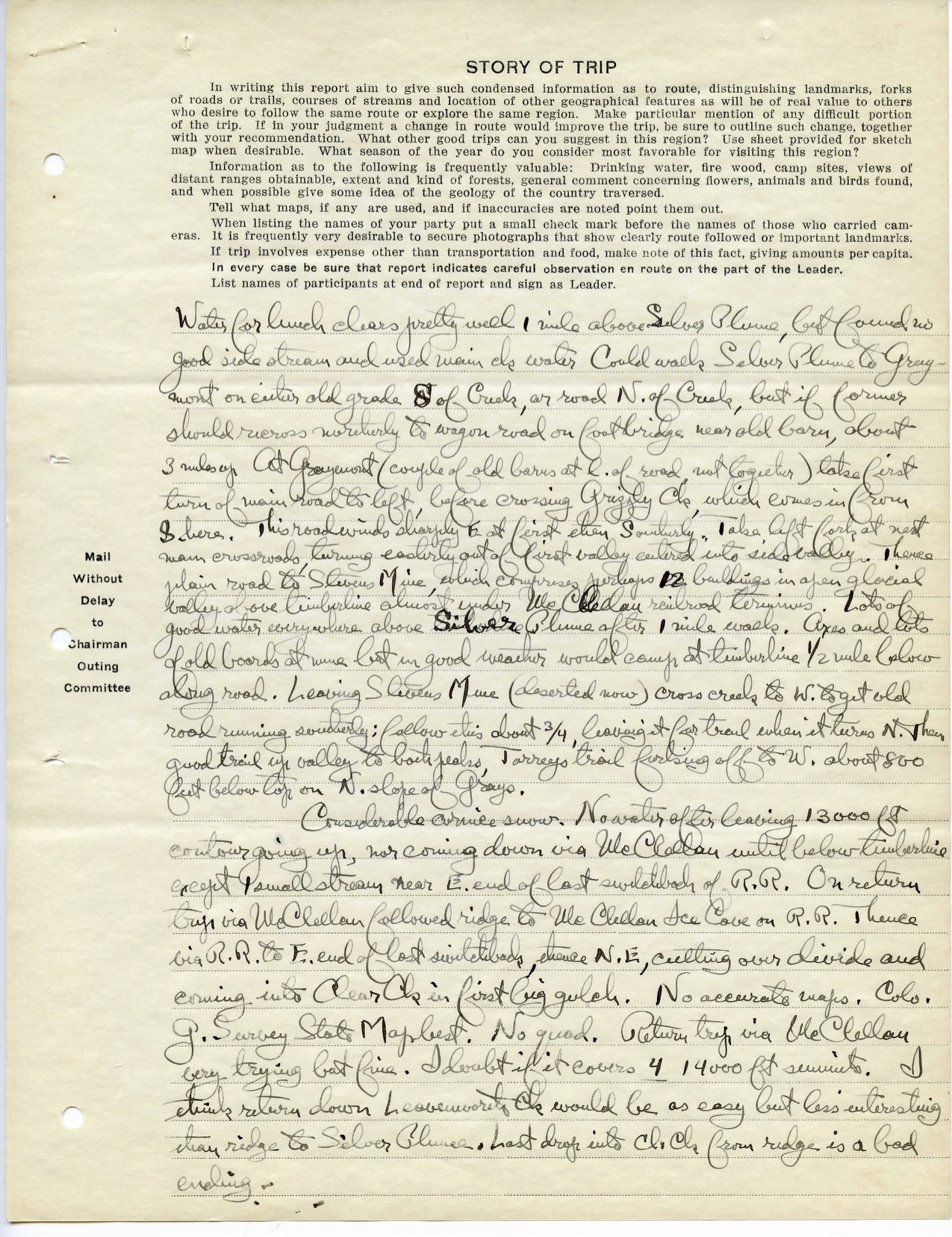

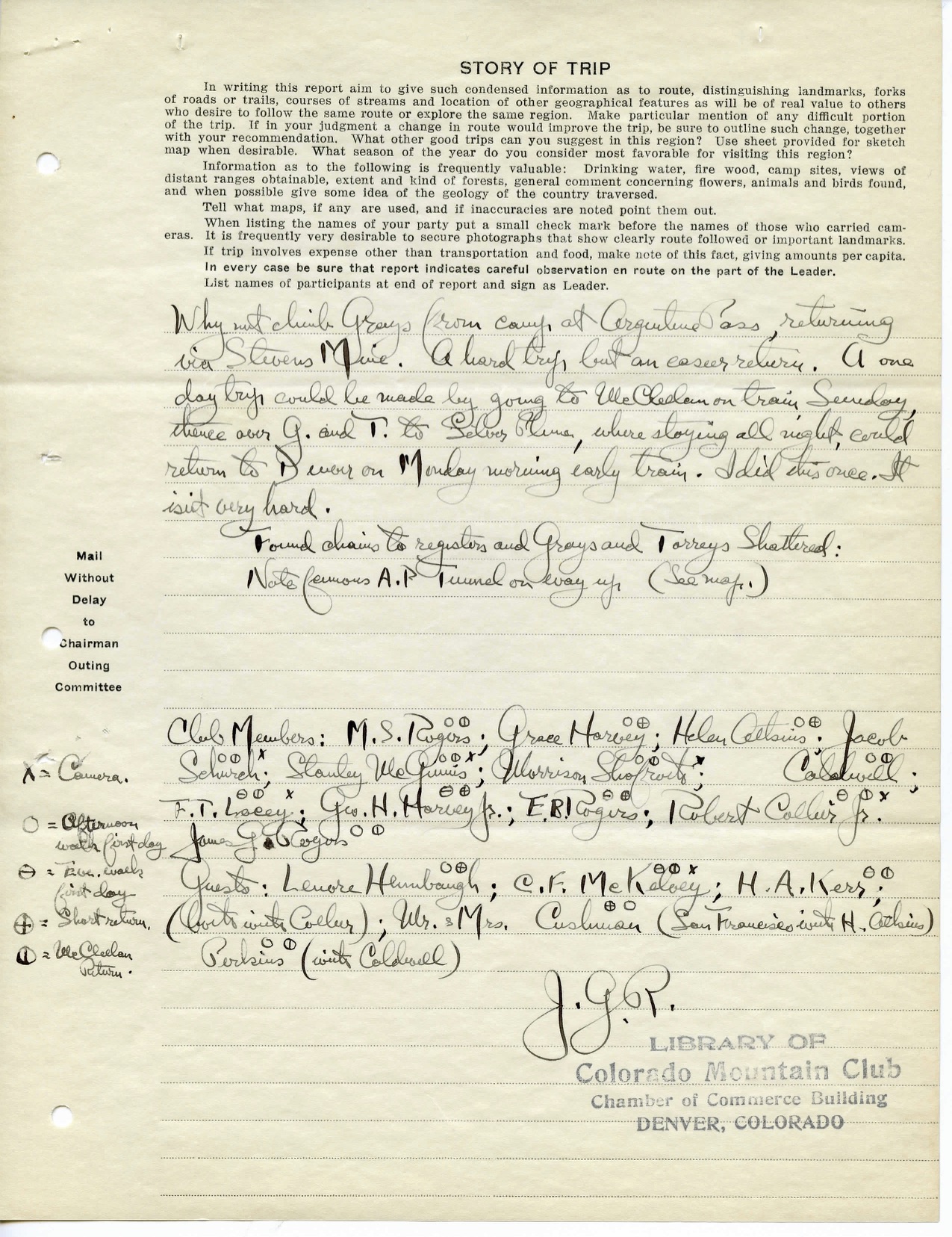

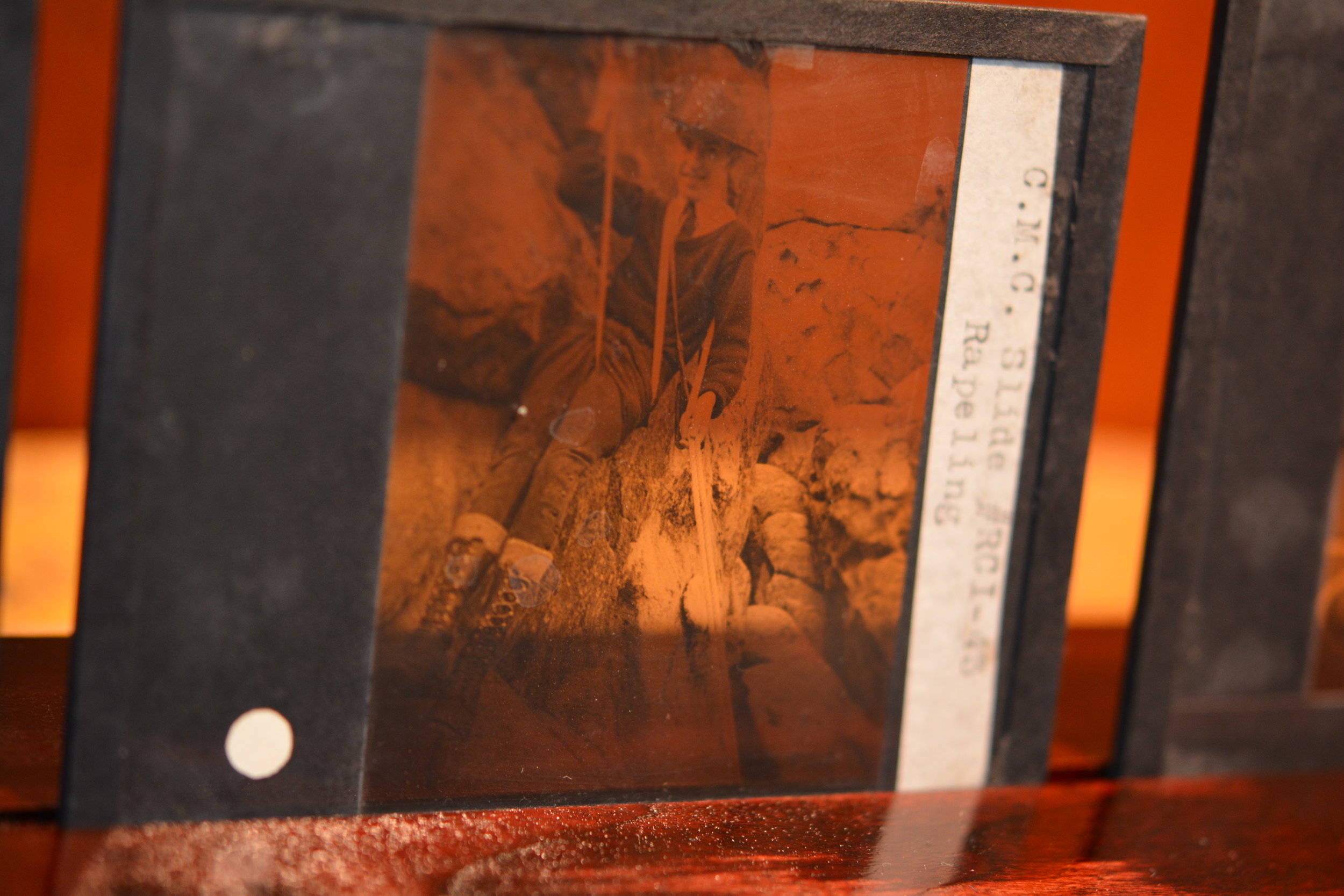

The archives date back to before the founding of the Colorado Mountain Club in 1912. There are trip reports, photographs, lantern slides, scrapbooks, old gear, 'Save the Wildflowers' posters, and much more. Currently, most of the early trip reports (over 1,150) have been digitized and eight photo scrapbooks. We are gradually adding them to our Digital Collections website. As we create and catalog finding aids, you can find them in our catalog here.

Putting It All Together

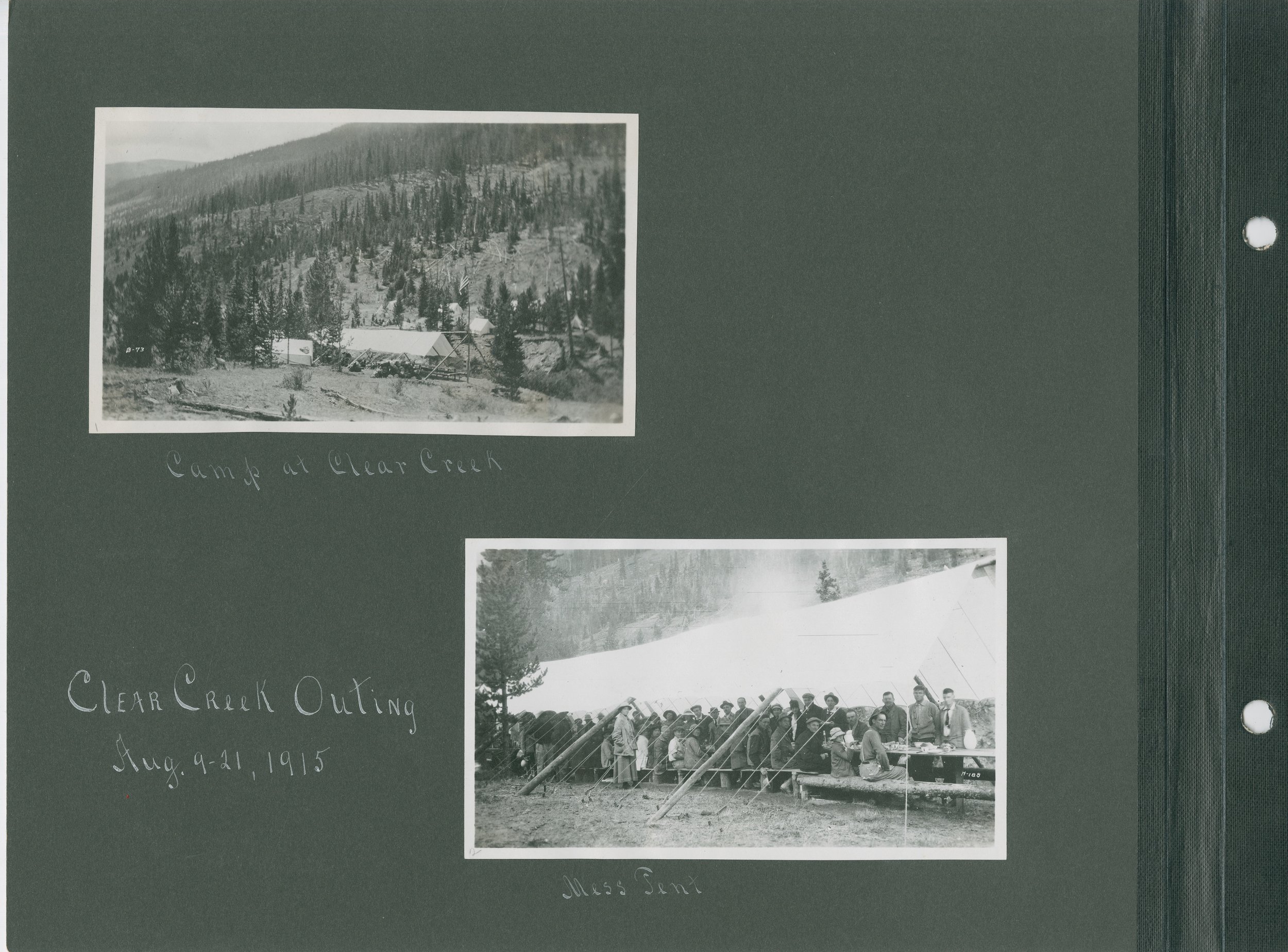

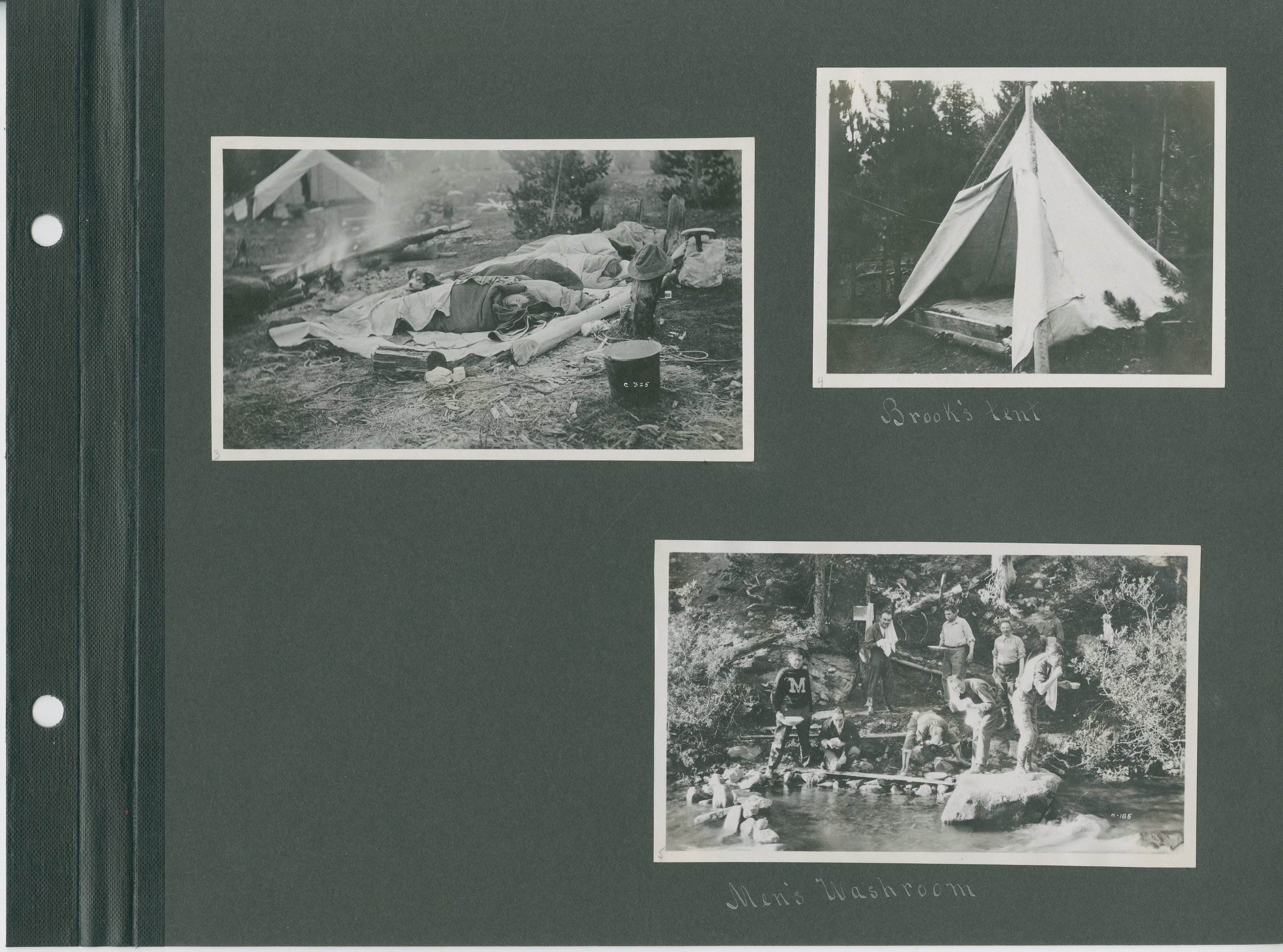

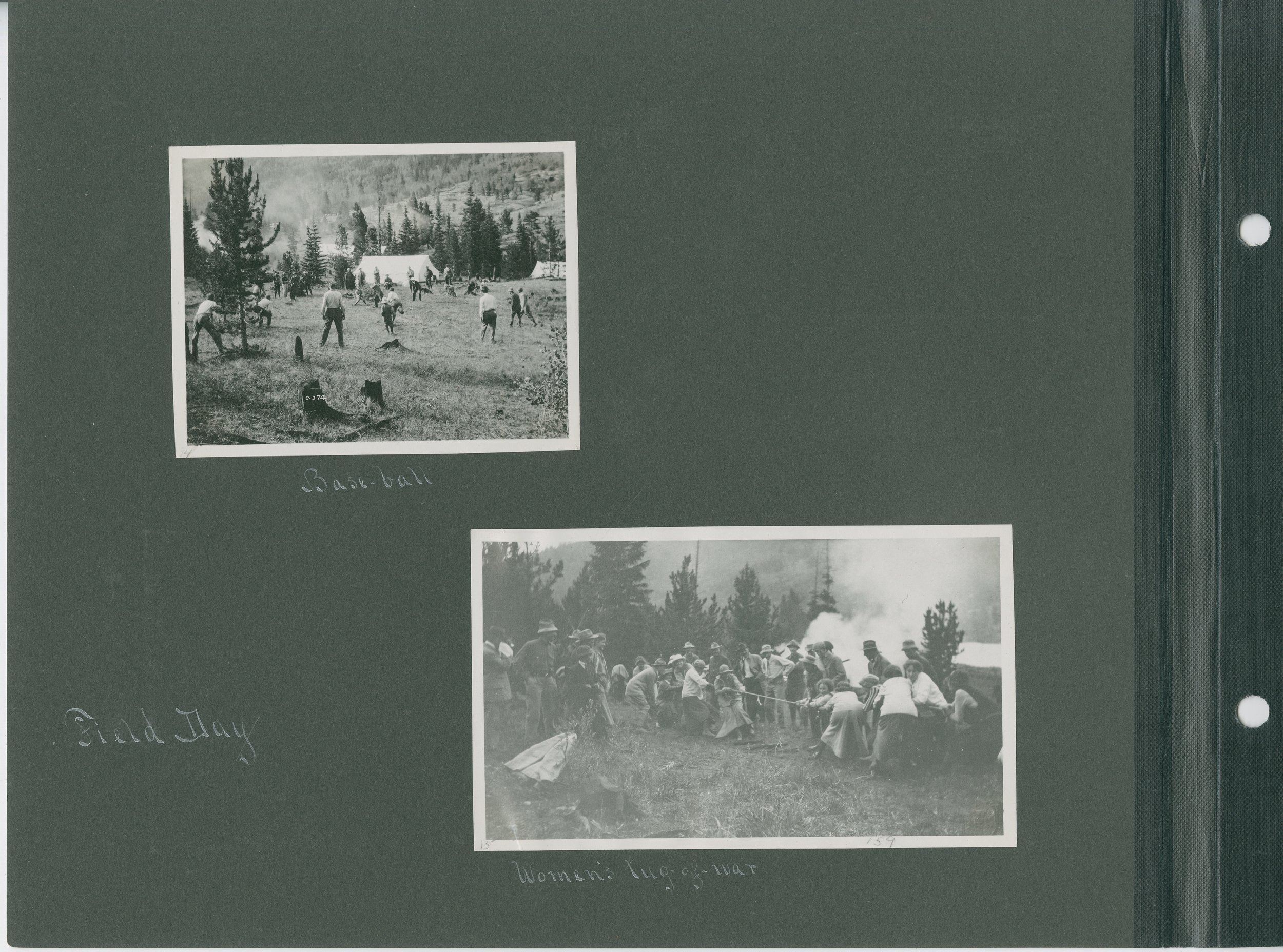

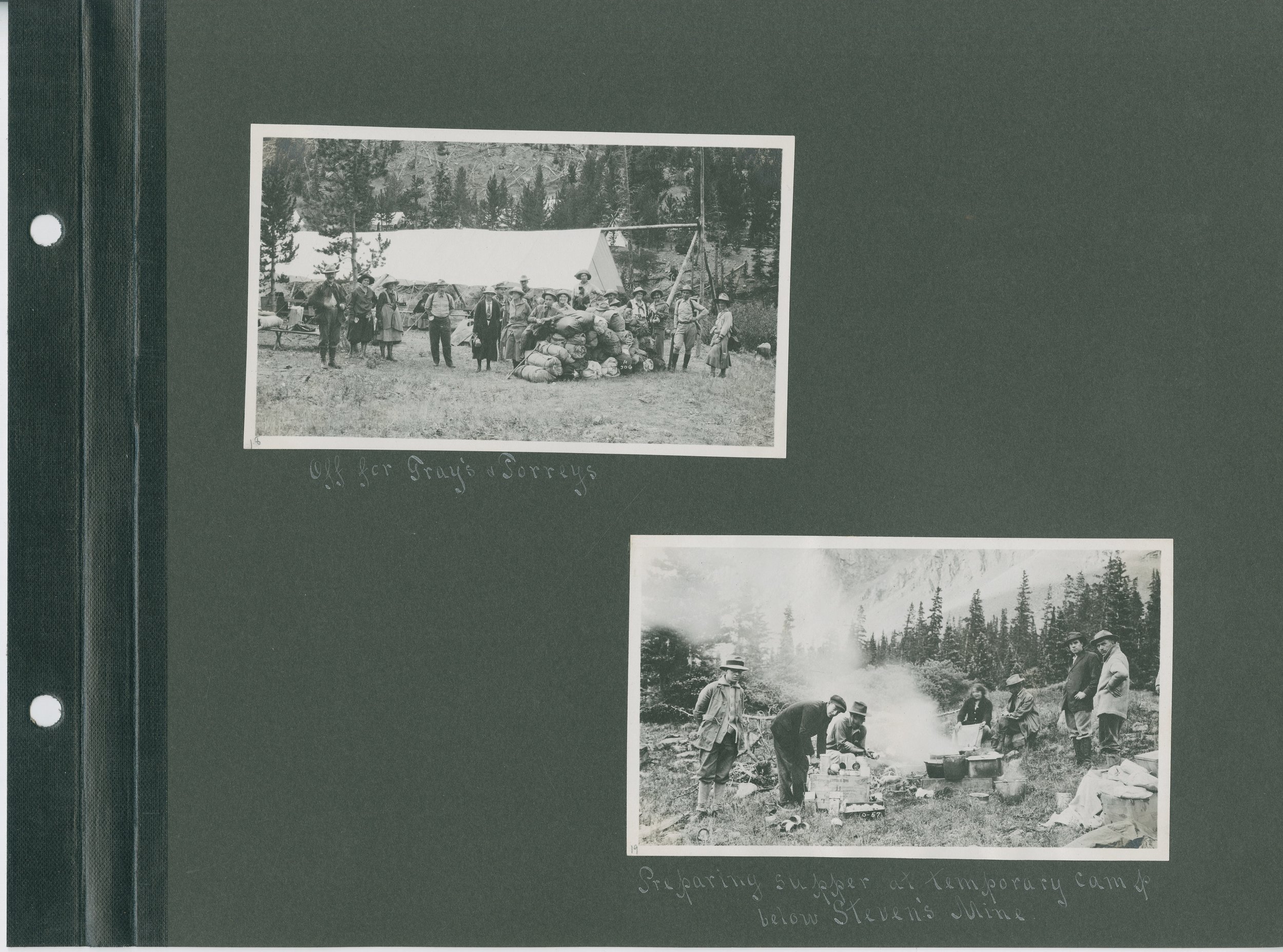

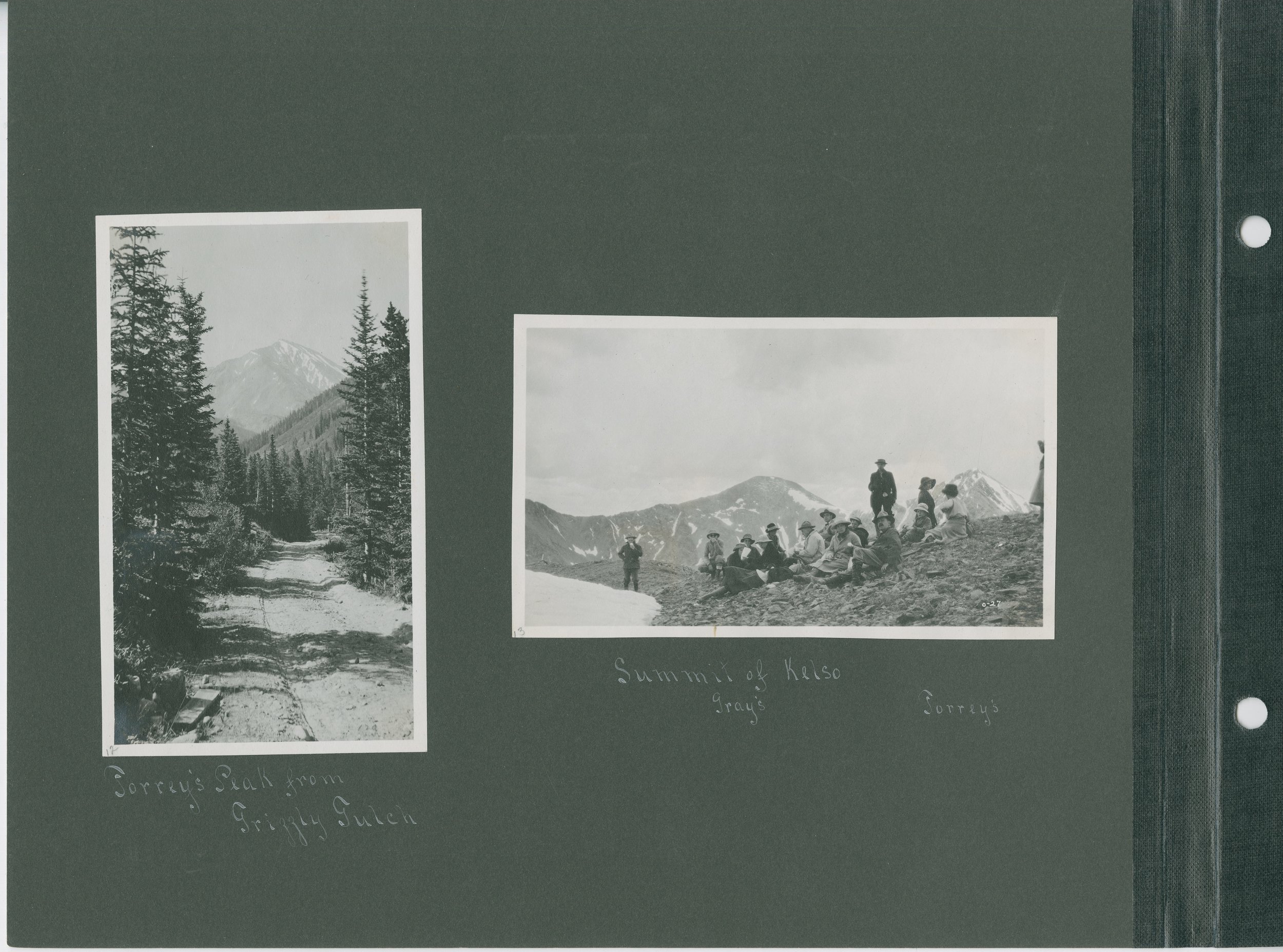

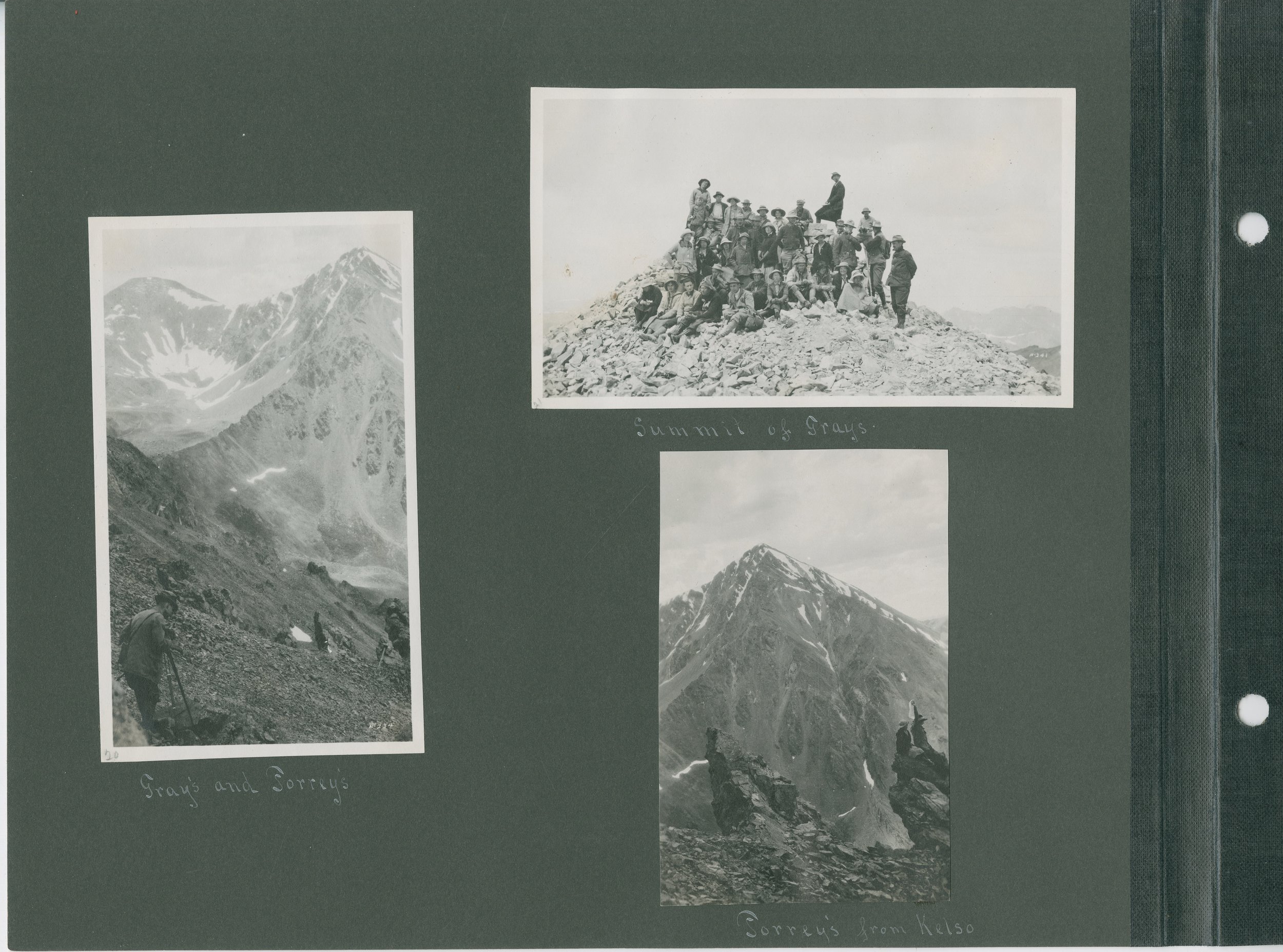

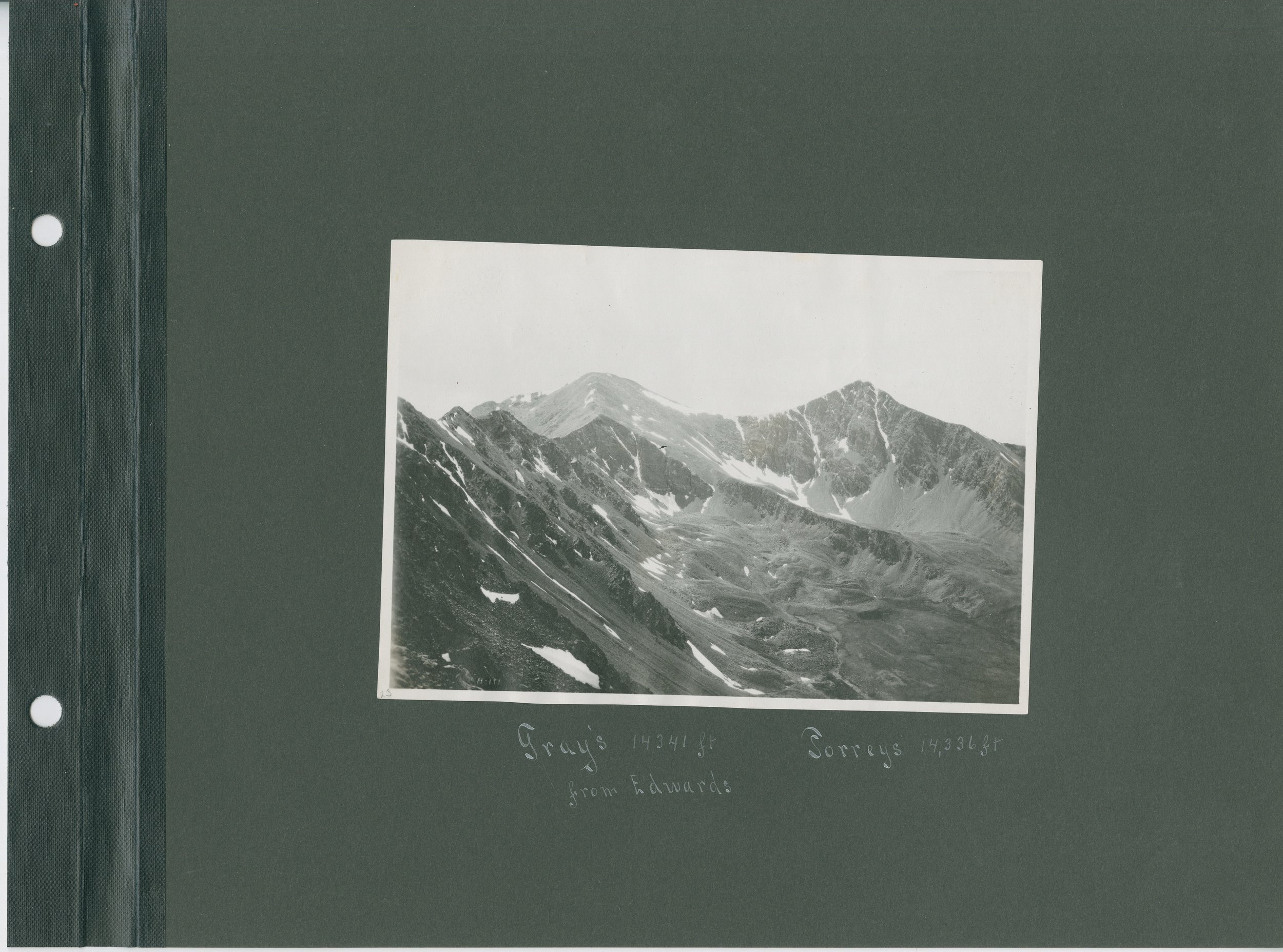

Having all of these records inventoried and cataloged makes it so much easier for researchers to find information. For example, you can now find photographs from the 1915 Clear Creek Outing on our Digital Collections website, with a selection seen below.

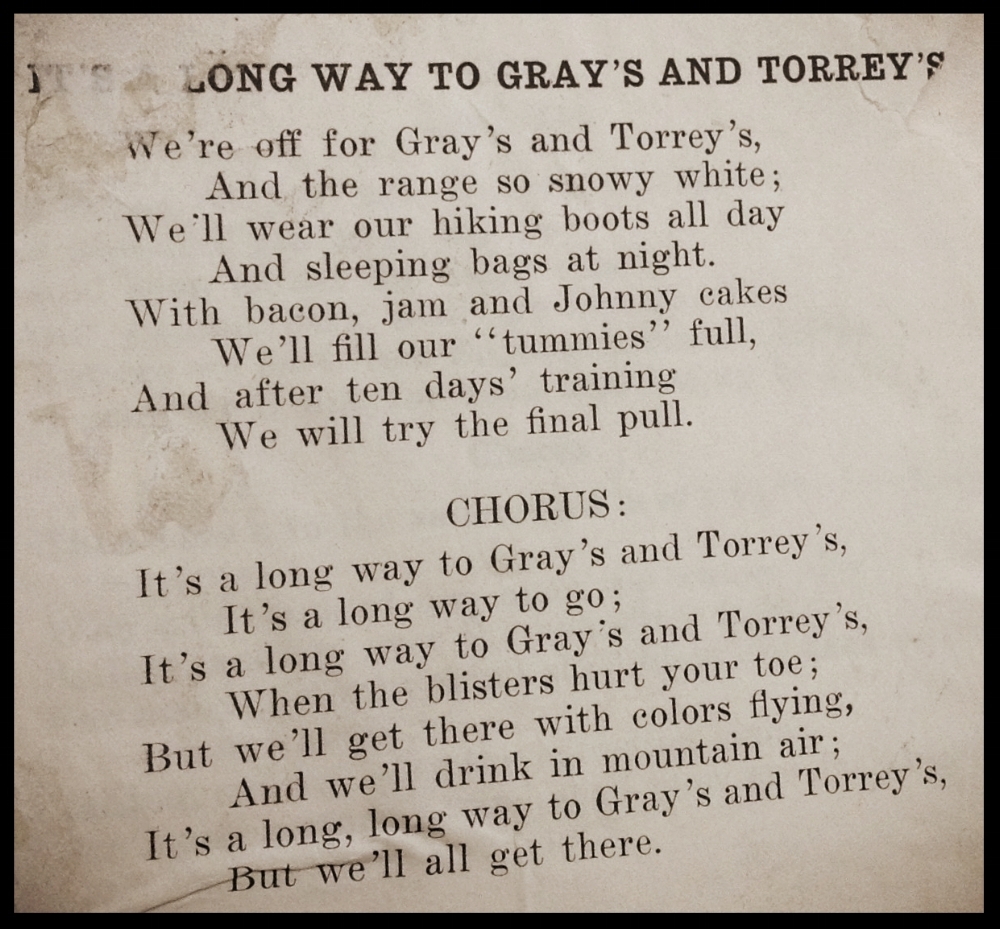

By searching the inventories, you can pair those photographs with the Song Book written by the Club members, the Grays and Torreys trip report and the summit registers that were signed by the CMCers when they climbed Grays and Torreys on August 20, 1915.

There are many more great records. Feel free to drop by the library and take a look. Keep an eye on our Digital Collections website as we are constantly adding more photographs and records.

This project was supported in part by an award from the Colorado Historical Records Advisory Board, through funding from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC), National Archives Records Administration. This project would not have been possible without the volunteers that inventoried, sorted, boxed, re-foldered, and scanned. Many thanks to Donna Anderson, Karyn Bocko, Dan Cohen, RoseMary Glista, Ann Hudgins, Peter Hunkar, Mike Lovette, Jan Martel, Barbara Munson, Roxy Rogers De Sole, Linda Rogers, Lin Wareham-Morris and Pat Yingst.

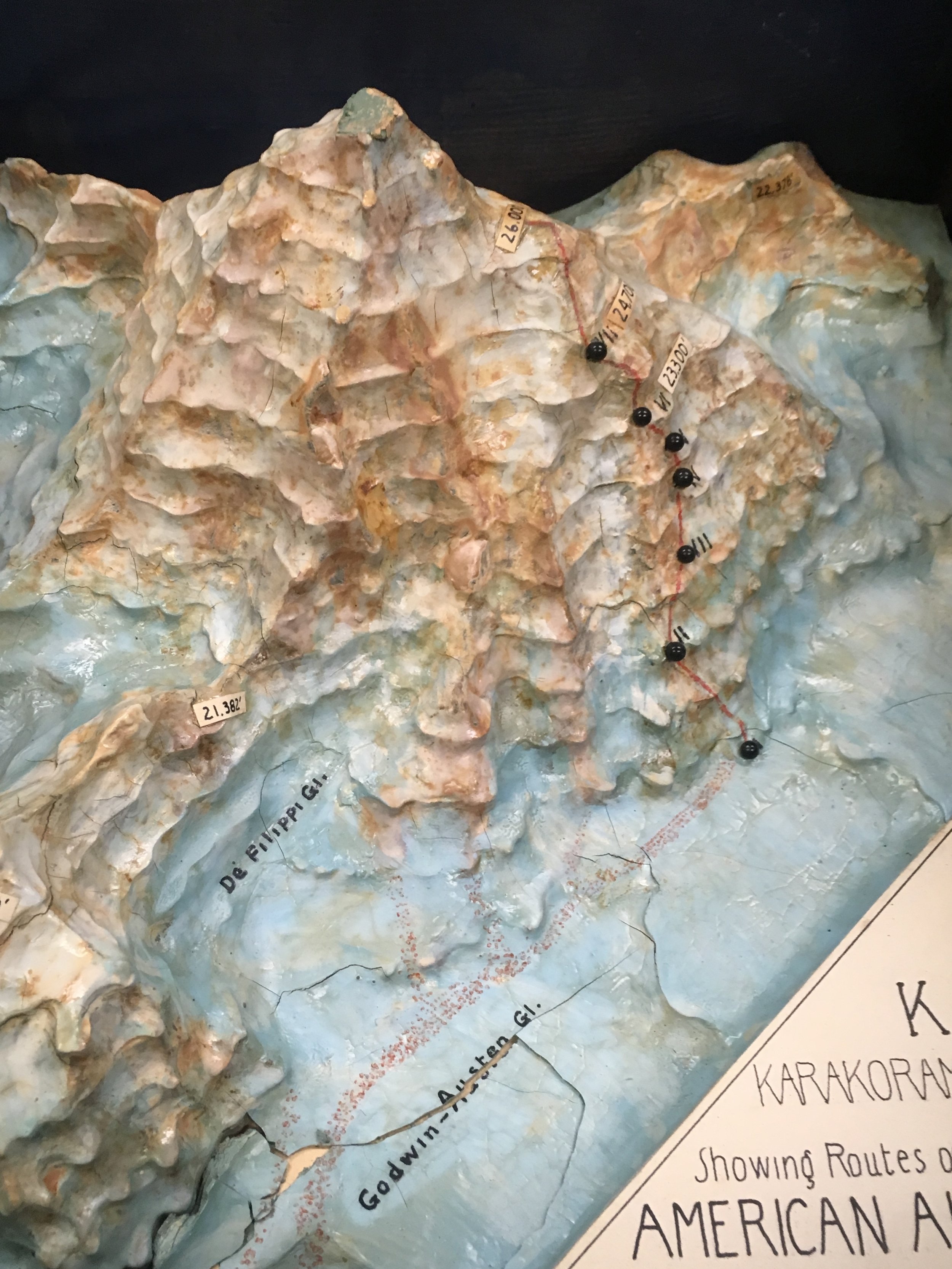

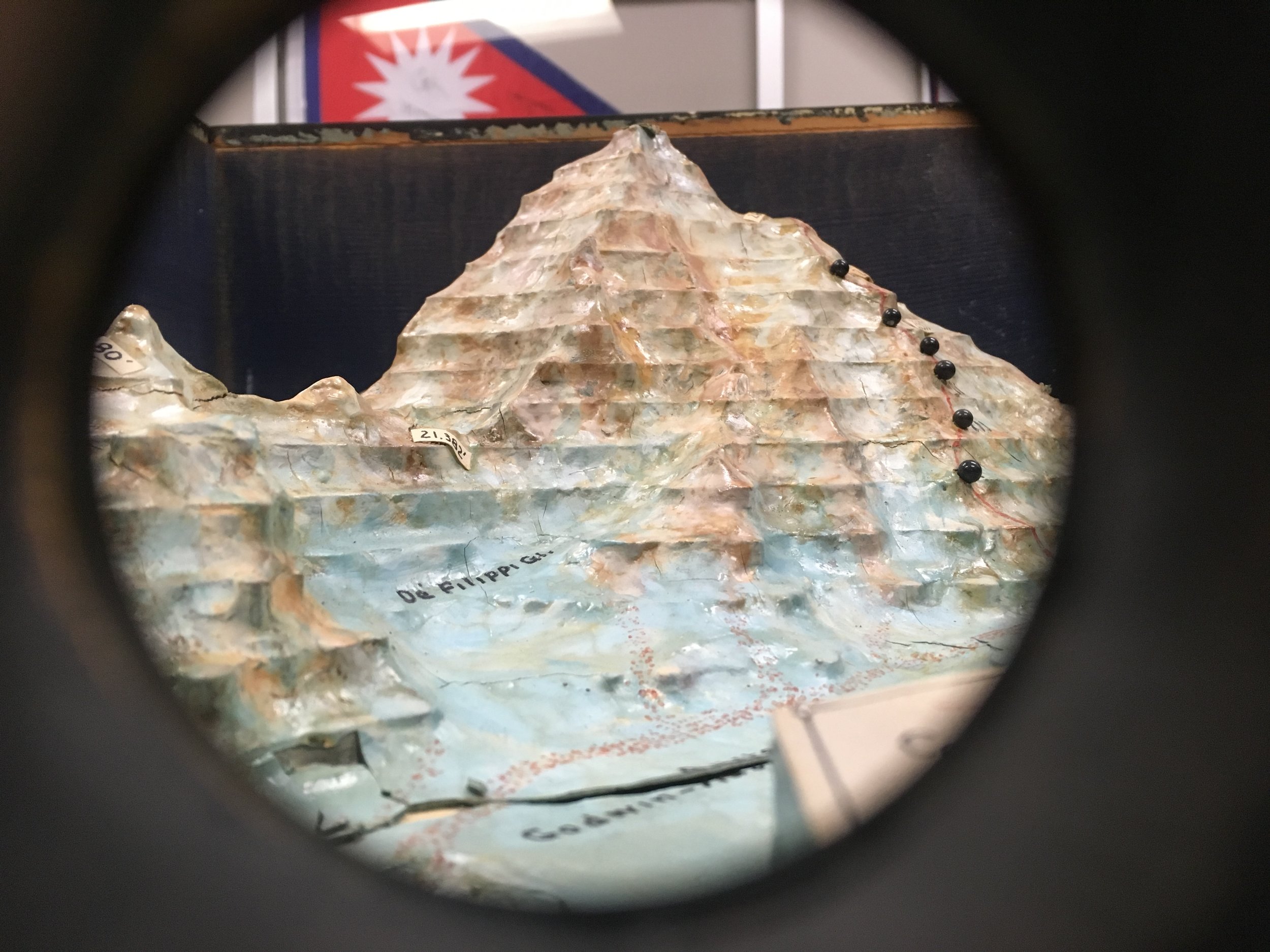

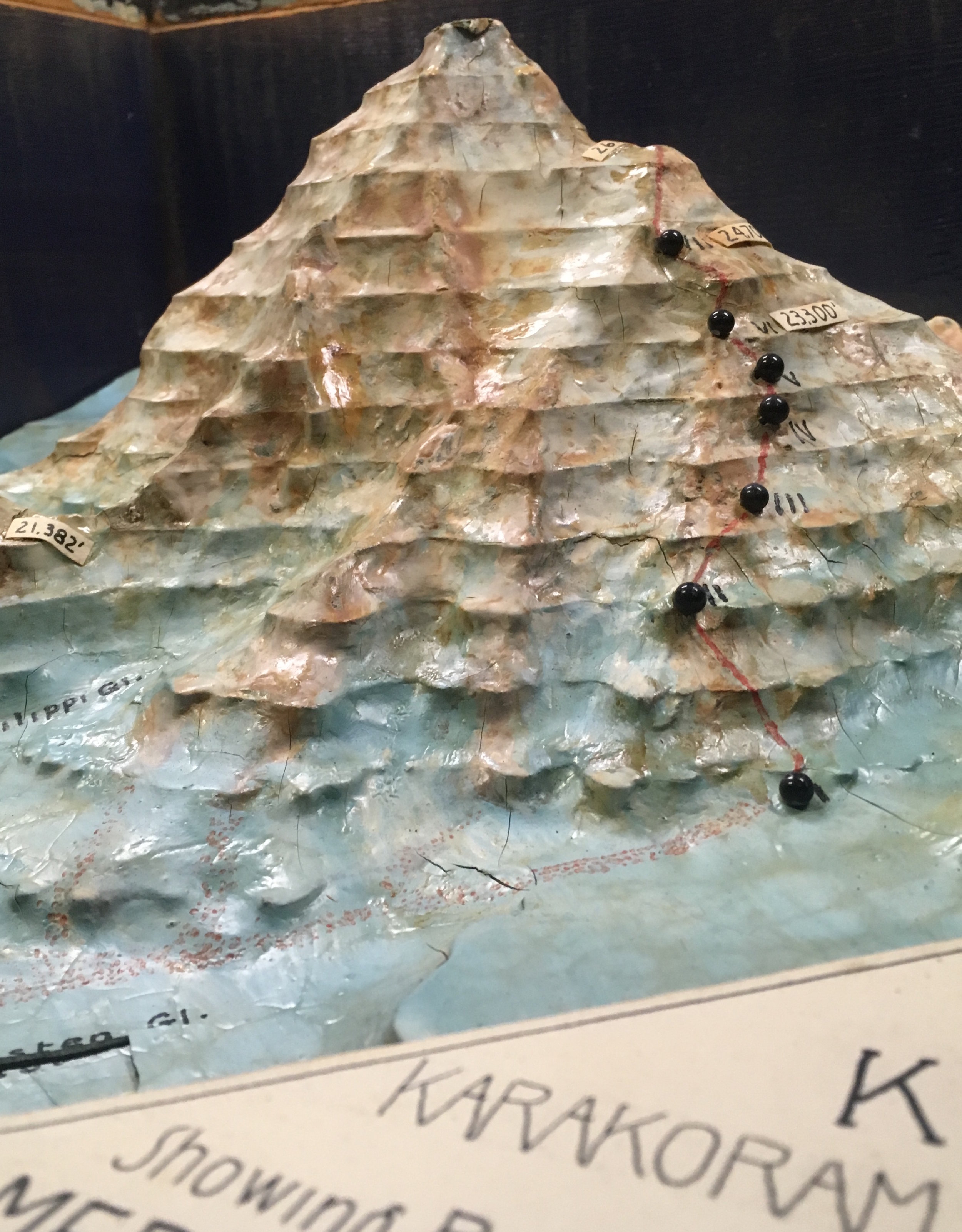

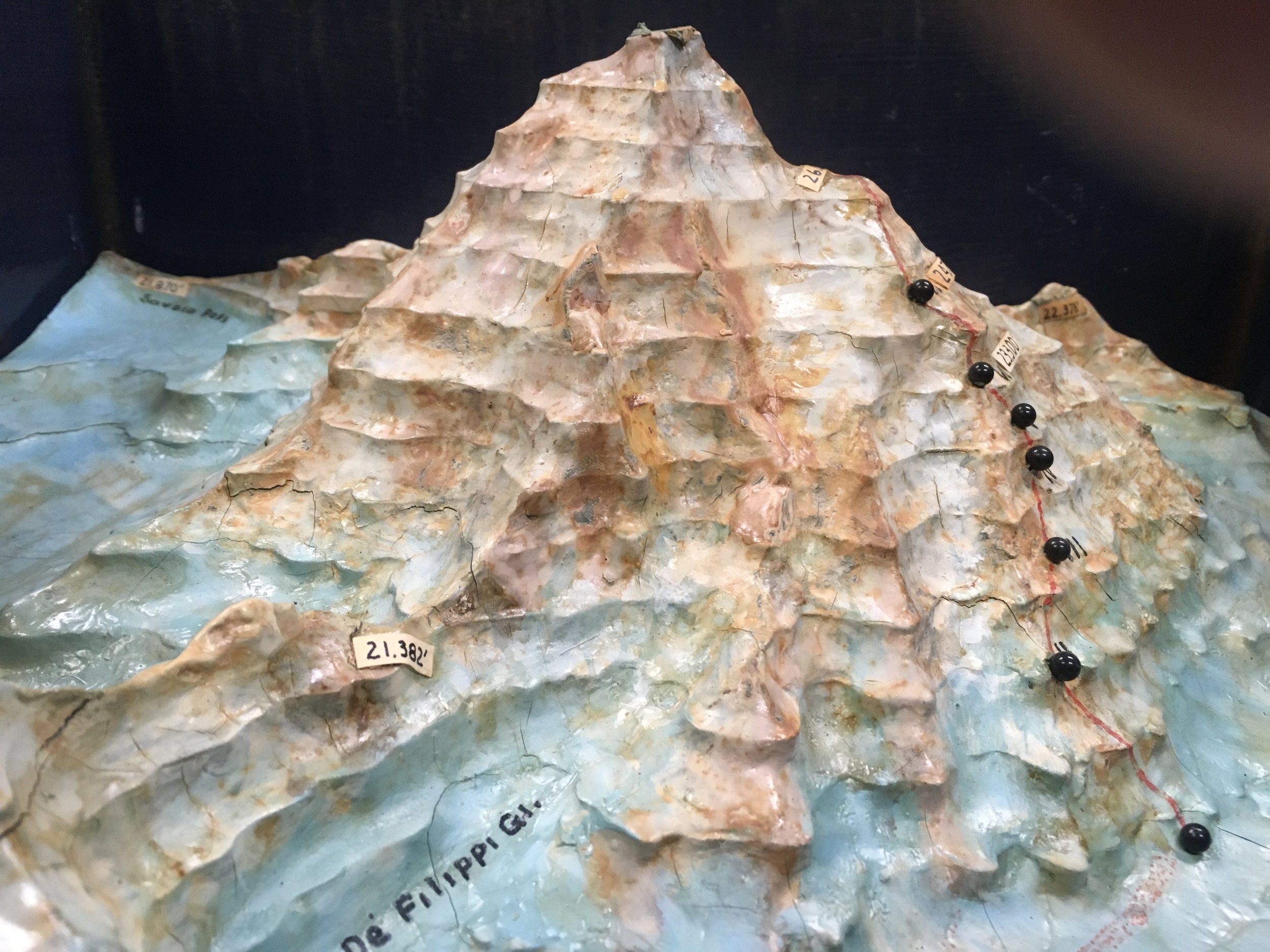

K2 1938: The First American Karakoram Expedition

by Eric Rueth

On February 24, The American Alpine Club will celebrate the first American ascent of the world’s second-highest peak, K2, at our Annual Benefit Dinner in Boston. It’s been 40 years since Jim Whittaker led an American expedition to the Savage Mountain but the history of American expeditions to the mountain goes back much farther and is one mired in adventure, tragedy and heroism.

Photograph of K2 from the Baltoro Glacier, taken by Vittorio Sella in 1909. Vittorio Sella Collection

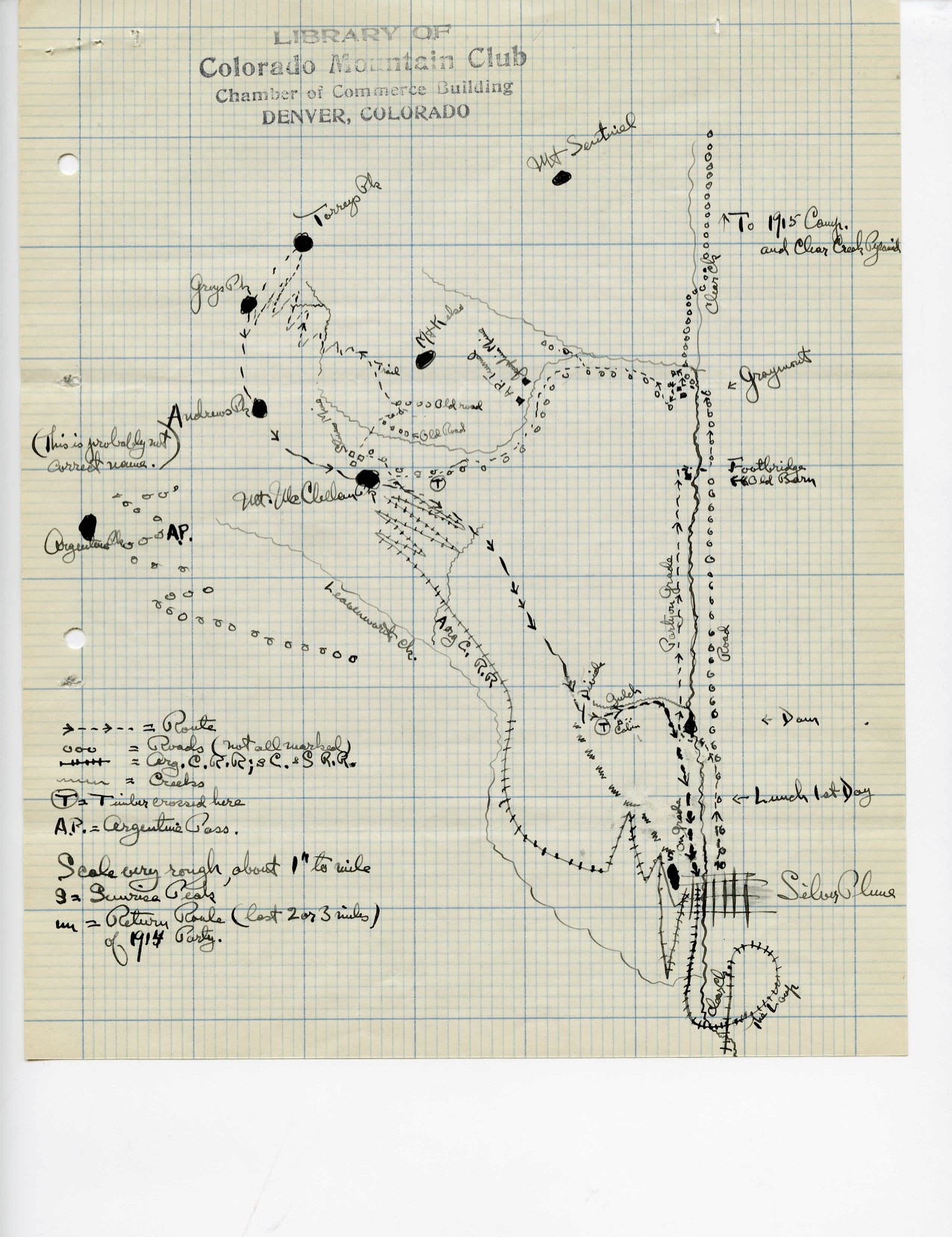

The first American expedition to K2 took place in 1938. This was not only the first American expedition to the mountain but the 3rd ever attempt on the mountain and the first since the Duke of Abruzzi attempted K2 in 1909. The American Alpine Club had acquired permits to K2 for 1938 and 1939. With permits for back-to-back years, the main focus for the 1938 expedition was to reconnoiter the mountain and three ridges to determine the best route to the top. Of course if the opportunity presented itself they should reach the summit.

After evaluating photographs and surveys of the area from previous expeditions, it was determined that there were five potential routes. This meant there were five routes that had to be explored and hopefully at least one with a viable route to the summit.

The party, given the task that was laid before them, was relatively small. It included Charles Houston, Robert Bates, Paul Petzoldt, Richard Burdsall, Bill House, Captain Norman Streatfeild (British Liaison Officer), 6 Sherpa porters and 3 camp men.

On May 13, 1938 the party departed Srinagar to begin their 362-mile approach. After a month the confluence of the Savoia and the Godwin-Austen glaciers was reached on June 12. The confluence of the glaciers provided a centralized basecamp that allowed the expedition to have relatively easy access to both glaciers for reconnaissance.

Once base camp was established at 16,600 ft., the first task was to reconnoiter the Northwest Ridge. The ridge looked promising in photographs taken by the Duke of Abruzzi’s expedition, and two of his guides had reached the Savoia Pass on the ridge. After navigating over the crevasse covered glacier, Houston and House reached the bergschrund only to find disappointment in the form of hard green ice. It was fewer than 800 feet to better terrain above but they determined that chopping steps into the ice would be too consuming of time and energy and would be a dangerous link in the chain of camps up the mountain if the Northwest ridge offered a viable route. Fortunately, Petzoldt and Burdsall spied a rock route that they believed could unlock the ridge. When House and Petzoldt made an attempt to see if the rock route would go, they were met with unfavorable weather and had to abandon the thought for the moment.

On June 19th the entire party convened at basecamp to discuss what had been discovered thus far and how to proceed. Bates and Burdsall had made a trip down the Godwin-Austen Glacier and through brief clear weather windows were able to completely rule out the south face due to avalanche danger. After a good look at the Abruzzi Ridge, they reported that it didn’t look promising.

The northwest ridge wasn’t out of the question, but the obstacle of ice would be a time consuming one. So, the focus shifted to the east side of the mountain. The expedition would get a close look at the Abruzzi Ridge and the northwest ridge and return to the Savoia glacier if no route seemed better than what had already been discovered on the northwest ridge.

Continuing with the trend, the first views from the east side of K2 were not positive. The northeast ridge is a long knife-edge ridge littered with gendarmes. The south side of the ridge seemed like it could go but would require long stretches of travel through icy gendarmes that could topple over onto anyone traveling beneath them. The north side was prone to avalanches from high up the mountain and neither appeared to offer sites suitable for establishing camps. The Abruzzi Ridge at least looked possible, though difficult.

After the first views of these two ridges it was decided that Houston and House would climb the Abruzzi Ridge to determine the difficulty of climbing. On the first day of exploration of the ridge Houston discovered some small pieces of wood, these were remnants of the Duke of Abruzzi’s highest camp in 1909 and provided a psychological boost to the climbers. As they carried on up the ridge, the climbing grew more difficult and no suitable campsites were found. With the Karakoram’s penchant for sudden poor weather, the lack of adequate campsites was more concerning than the difficulty of climbing.

Photograph of K2 from Windy Gap, taken by Vittorio Sella in 1909. Vittorio Sella Collection

Uncertainty began to set in. Three routes remained as options: the northwest ridge, the northeast ridge and the Abruzzi Ridge. The big problem was that none of the routes seemed particularly better than the others. Each ridge had its own question looming over it. Could the northwest ridge be reached without devoting a lot of time and energy to carve out steps? Was there a potential route hidden on the northeast ridge that would not place the climbers in extreme danger? Were there any suitable locations to place campsites on the Abruzzi Ridge?

The party attempted to answer two of these questions. Bates and House returned to the Savoia Glacier. A few days of roaring avalanches off of the west face of K2, tumbling seracs, traversing ice slopes and heavy snow saw the pair reach a high point of 20,000 ft. before the rock became too steep. They came to the conclusion that reaching the northwest ridge under the current conditions was not possible.

Houston and Streatfeild had an easier time on the northeast ridge; easier in that they realized after several hours of step cutting that the route would not be adequate for carrying loads and the ridge offered little protection for any campsites that could be established.

So the Abruzzi Ridge was all that remained. As the last viable option all efforts and resources would now focus on the Abruzzi Ridge. Camp I was established at its base at 17,700 ft. While the rest of the expedition ferried loads to stockpile Camp I, Petzoldt and House continued scouring the ridge for campsites. After a day of searching and ascending a steep snowfield, hopes were waning and the pair was about to descend back to Camp I. Petzoldt decided to ascend one more pitch to peek around the corner of a crest. When Petzoldt reached the end of the rope, he let out an excited yell. Camp II was found. The campsite at 19,300’ was the first good news of the expedition since arriving the base of the mountain and lifted everyone’s spirits.

Rock taken from the Abruzzi Ridge. Karakoram translates to, "black gravel." Robert H. Bates Collection

Once Camp II was established and stocked with 10 days worth of supplies Petzoldt and House again led the way in search of the next camp. The ground grew steeper and steeper with any ledges discovered sloping downward. Once again the prospect of finding a campsite seemed slim and hopes began to waver. Around noon, as the going became more and more difficult, the pair noticed two buttresses a few hundred feet above them that may yield suitable terrain. With haste House began the first of two ice traverses that lay between them and the buttress. In an effort to save time House cut as few steps as possible. This time-saving maneuver led to House losing purchase and sliding towards the Godwin-Austen Glacier. Petzoldt was prepared for this possibility and held fast to the rope around House’s waist. After banging into the buttress that Petzoldt belayed from, House attacked the ice slope with new vigor. House completed the traverse placing pitons and running rope along the way. The reward for the day’s climbing was a tiny, uneven platform that sloped off the mountain on three sides.

Before Camp III (20,700 ft.) could be established Petzoldt and House needed to safeguard the route with 900 ft. of rope. The treacherous terrain was difficult for two unloaded men; it would be near impossible and reckless to attempt with a full load of supplies. The task of safeguarding the route took the entirety of the next day and still not satisfied with its security, was reinforced more as light loads were carried towards Camp III the day after that. Before the light loads could be brought all the way to Camp III, a storm began to build. The loads were left below a buttress and the pair descended all the way to Camp I when it appeared that the storm was gaining strength and was potentially going to be a long one.

The storm was not prolonged and the next day was relatively clear. With extreme caution, loads were carried to Camp III and more ropes placed to further secure the treacherous sections of the route. After 4 days of ferrying loads while snow fell and winds howled around them it was time to go higher than Camp III and search for Camp IV.

Petzoldt and Houston led the way in search of Camp IV. The climbing above Camp III grew more technical, the rock grew more rotten and was eventually blocked by a large gendarme. Petzoldt conquered the obstruction via an overhanging crack that led to a ledge with solid holds. A few hundred feet above the recently defeated gendarme another obstruction was reached, this time it was an impassable wall of reddish-brown rock. The duo descended back to the top of the gendarme and decided that it would be the location for Camp IV (21,500 ft.).

Once Camp IV was established it was time to push up the mountain. The new leaders were Houston and House. A location for Camp V was discovered at 22,000 ft., placing it only 500’ higher than Camp IV.

Above Camp IV the rock was near vertical and in worse condition than expected. This section was only climbed after House was able to work his way up an 80-foot chimney. The chimney now bears his name. Camp V was then located across a snowfield and under a rock pinnacle. This 500’ took four hours to achieve and would be an entire days work when moving supplies. House’s Chimney was impossible to climb with a load so a makeshift aerial tramway was constructed to haul the loads up.

After a few days of poor weather and load ferrying, a site for Camp VI was discovered at 23,300’. The climb up to Camp VI took serious skill in route finding and saw Petzoldt and Houston turned back at multiple points. Eventually they discovered a steep snow gully that tested their nerves. The snow was deep and anything that fell down the gully disappeared into nothingness. The snow gully led to more rotten rock, which led to a buttress whose base would be the location for Camp VI.

Above Camp VI lay the black pyramid, a near 1,000-foot buttress of dark rock that loomed over the expedition while they were scouting the ridge a month earlier. If they could make their way up the black pyramid, K2’s 2,200-foot summit cone would be within reach.

Petzoldt and Houston worked their way up the route; Petzoldt, with fine intuition about where the path lay ahead, led over steep technical rock and eventually up another snow gully that led to the top of the pyramid. With the snow shoulder above the black pyramid reached, the Abruzzi Ridge was conquered. A handshake was shared and a “restful cigarette” enjoyed.

Thank you note written by Houston and Petzoldt on a piece of toilet paper. It reads:

"Hi

Thanks a million for the campsite and tent. They were certainly welcome when we came down at 4:15. Very cold.

We went 700 ft. higher over climbing of varying difficulty and spotted c/c weather. Route ahead not too bad. Hope to make top of pyramid today.

We hoped you could make two platforms more on this ledge and one near the big notch [?] feet below here.

Good luck + thanks again

C +P"

Robert H. Bates Collection

The route was pushed higher and a good campsite was found for Camp VII at 24,700 ft. Even after ropes were fixed on the difficult terrain between Camp VI and VII, the route would remain difficult and would be unwise to attempt in bad weather. With supplies dwindling it was time to make a decision.

The expedition conceded to K2 and the mountain remained unclimbed. With supplies dwindling and difficult terrain between camps a prolonged storm would potentially be catastrophic to the group, added onto that the porters were due to arrive in seven days.

Before retreating down the mountain, one final push would be made. Houston and Petzoldt would make a dash as high up the mountain as they could reach. A Spartan Camp VII was established with just enough supplies for Houston and Petzoldt to climb for a day. Any sign of bad weather would force the pair to make a hasty retreat to Camp VI.

The weather the next day was clear so the pair went up. Though K2 had provided many difficult and technical days of climbing, the final day was one of plodding through snow. By noon a recognizable shoulder was reached at 25,600 ft. The Duke of Abruzzi had triangulated the altitude 29 years earlier and the climbers knew that they had reached the summit cone. The pair climbed up a few hundred more feet to gain a good view of the route that led to the summit. Both agreed that it did not appear any more difficult than the route below and that the summit could be reached from the Abruzzi Ridge. They then turned and started back down the mountain.

Though their high point of 26,000 ft. was 2,250 ft. below the summit, the First American Karakoram Expedition was a success. The entire south side of the mountain was reconnoitered and a promising route to the summit was discovered. More importantly there were no major injuries and everyone involved survived the attempt high up the Savage Mountain. It was now up to the Second American Karakoram Expedition to climb the mountain.

Read about the Second American Karakoram Expedition here.

Read about the Third American Karakoram Expedition here.

By Eric Rueth

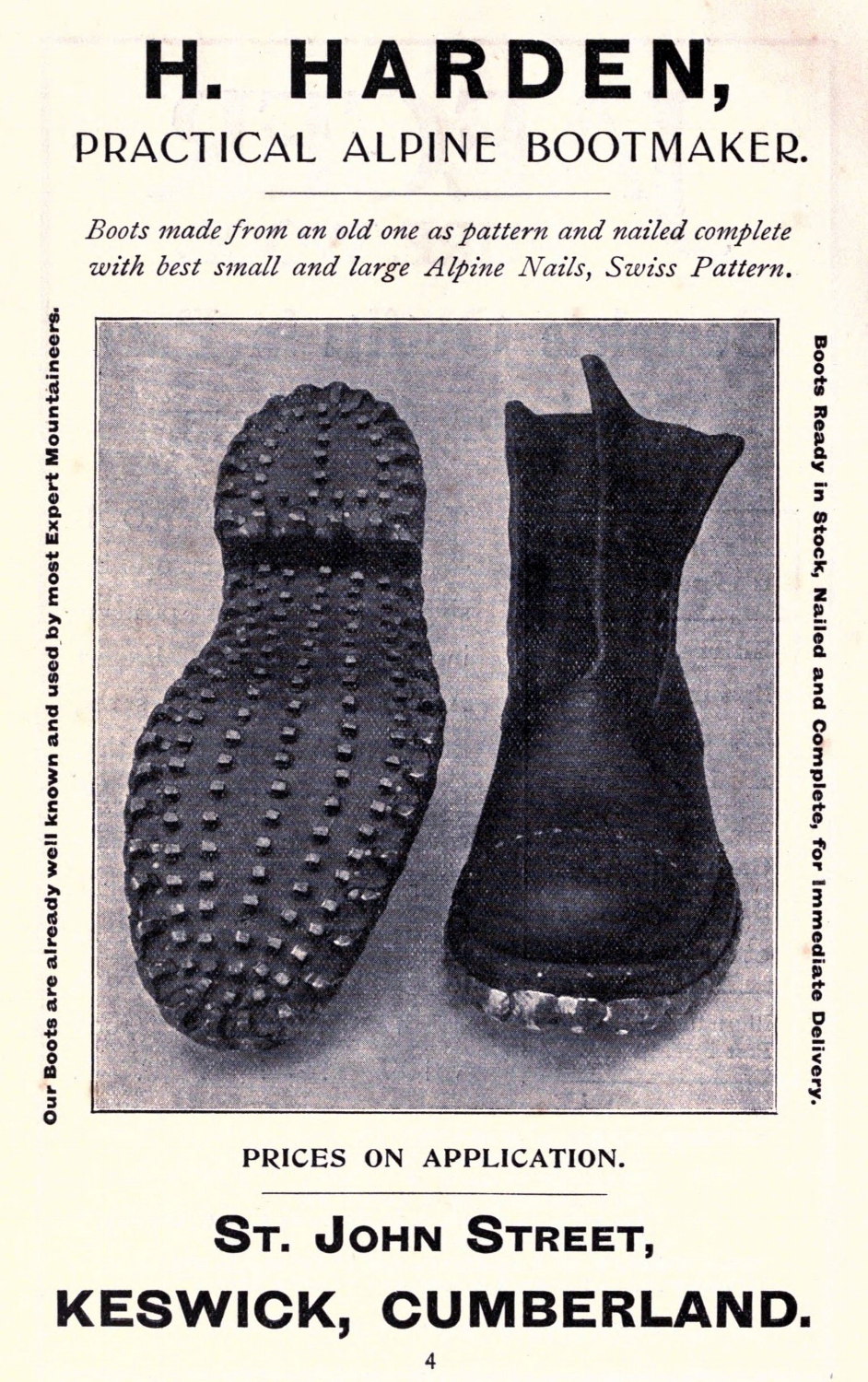

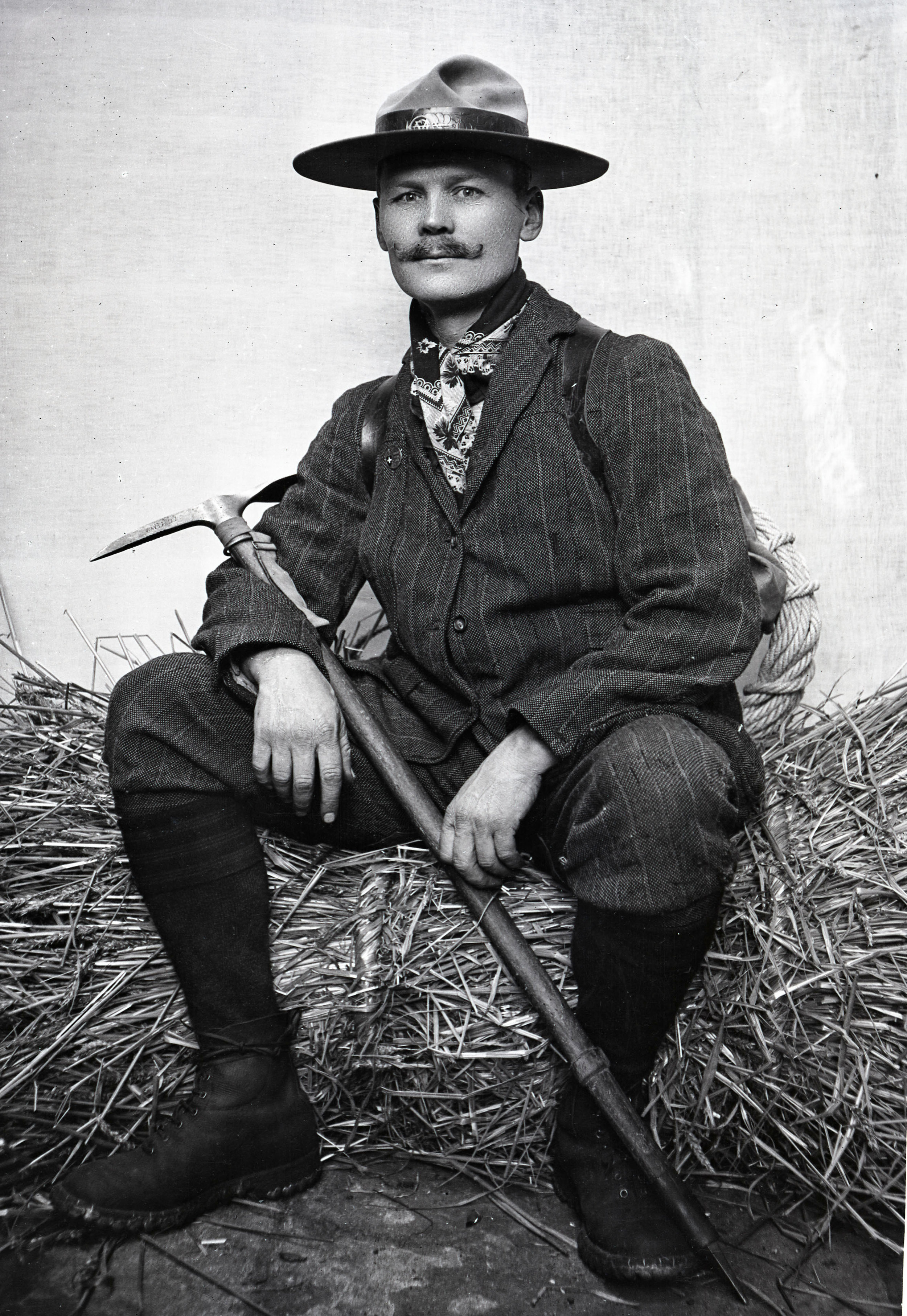

Mountaineering Boots of the early 20th century

A tale of horror and woe

by Allison Albright

Modern mountaineering boots are made to be comfortable, lightweight, insulated and waterproof. They're constructed of nylon, polyester, Gore-Tex, Vibram and involve things like "micro-cellular thermal insulation" and "micro-perforated thermo-formable PE." This technology costs anywhere from a couple hundred dollars to over $1000 and makes it much more likely for a mountaineer to keep all their toes.

We didn't always have it so good.

Mountaineering boots circa 1911.

By H. Harden - Jones, Owen Glynne Rock-climbing in the English Lake District, 1911, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9433840

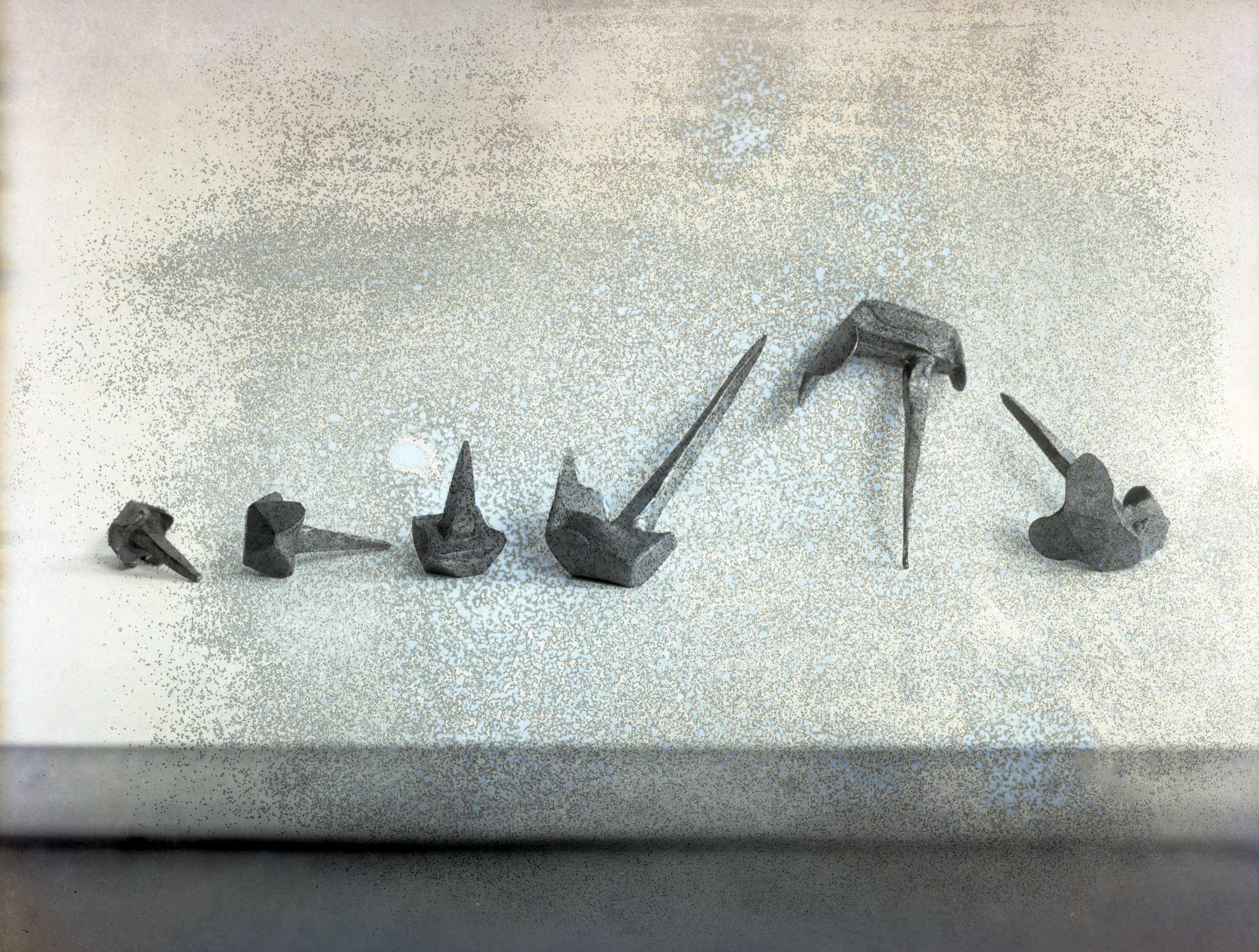

Early mountaineering boots were made of leather. They were heavy, and to make them suitable for alpinism it was necessary for climbers to add to their weight by pounding nails, called hobnails, into the soles.

“The very best boot is without a doubt the recognized Alpine climbing boot. Their soles are scientifically nailed on a pattern designed by men who understood their business; their edges are bucklered with steel like a Roman galley or a Viking’s sea-steed. No doubt they are heavy, but this slight inconvenience is forgotten as soon as the roads are left.”

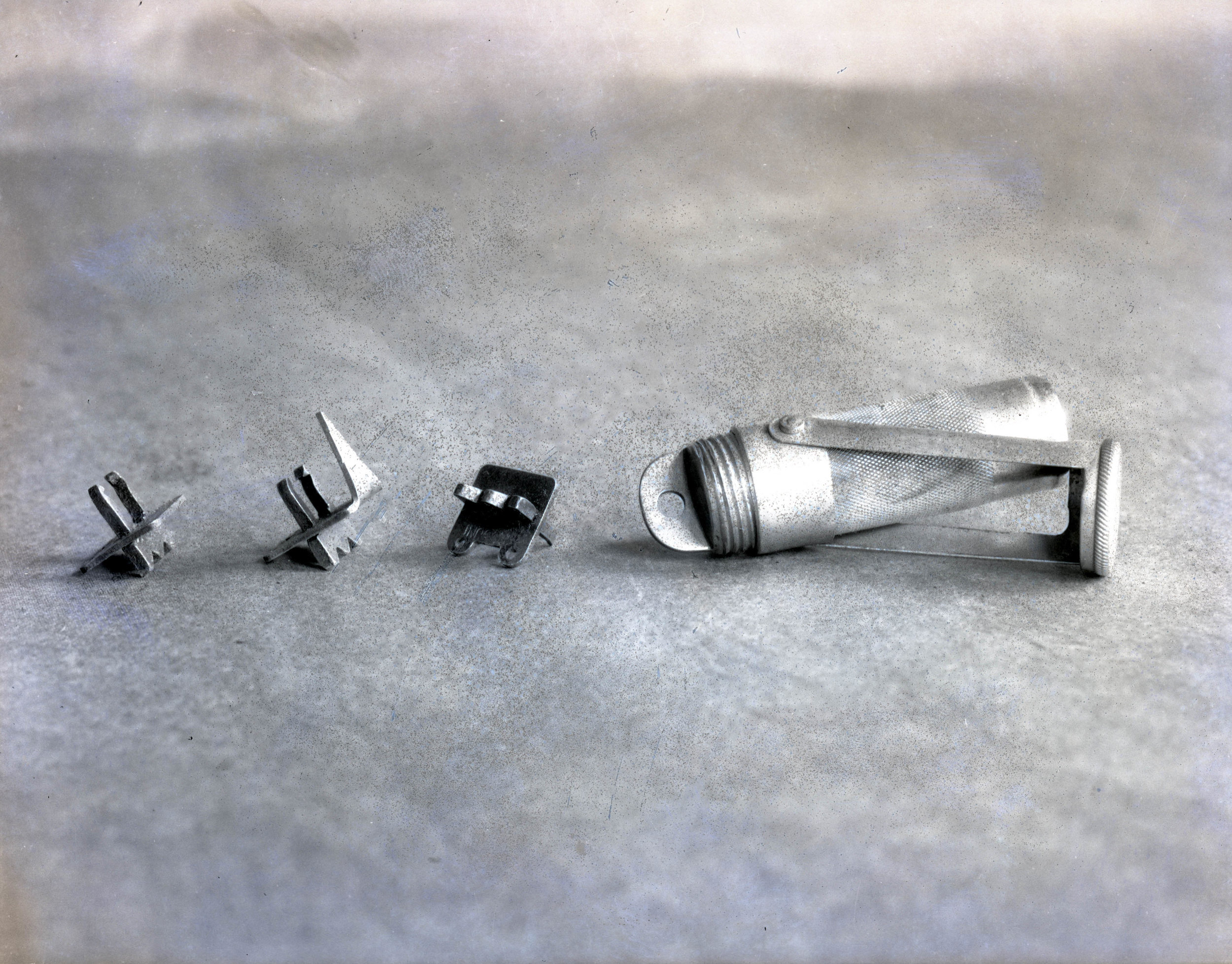

Tricouni nails were a recent invention in 1920 and could be attached to mountaineering boots to provide traction. They were specially hardened to retain their shape and sharpness.

Illustration from Mountain Craft by Geoffrey Winthrop Young. New York, 1920.

Illustration of boot nails from Mountaineering Art by Harold Raeburn, 1920.

In 1920 a pair of climbing boots went for about £3.00 - the equivalent of $28.63 in 2017 US dollars. However, climbers got much less for their money than we get out of our modern boots.

Original hobnails, stored in a reused box

“There is no use asking for “waterproof” boots; you will not get them.”

In addition to being heavy, the boots were not waterproof. Mountaineers had to apply castor oil, collan or melted Vaseline to the boots before each trip. This kept the boots flexible and also kept at least some water out. Animal fats were also an option, but they had a strong, unpleasant smell and would decompose, causing the leather and stitching of the boots to rot as well.

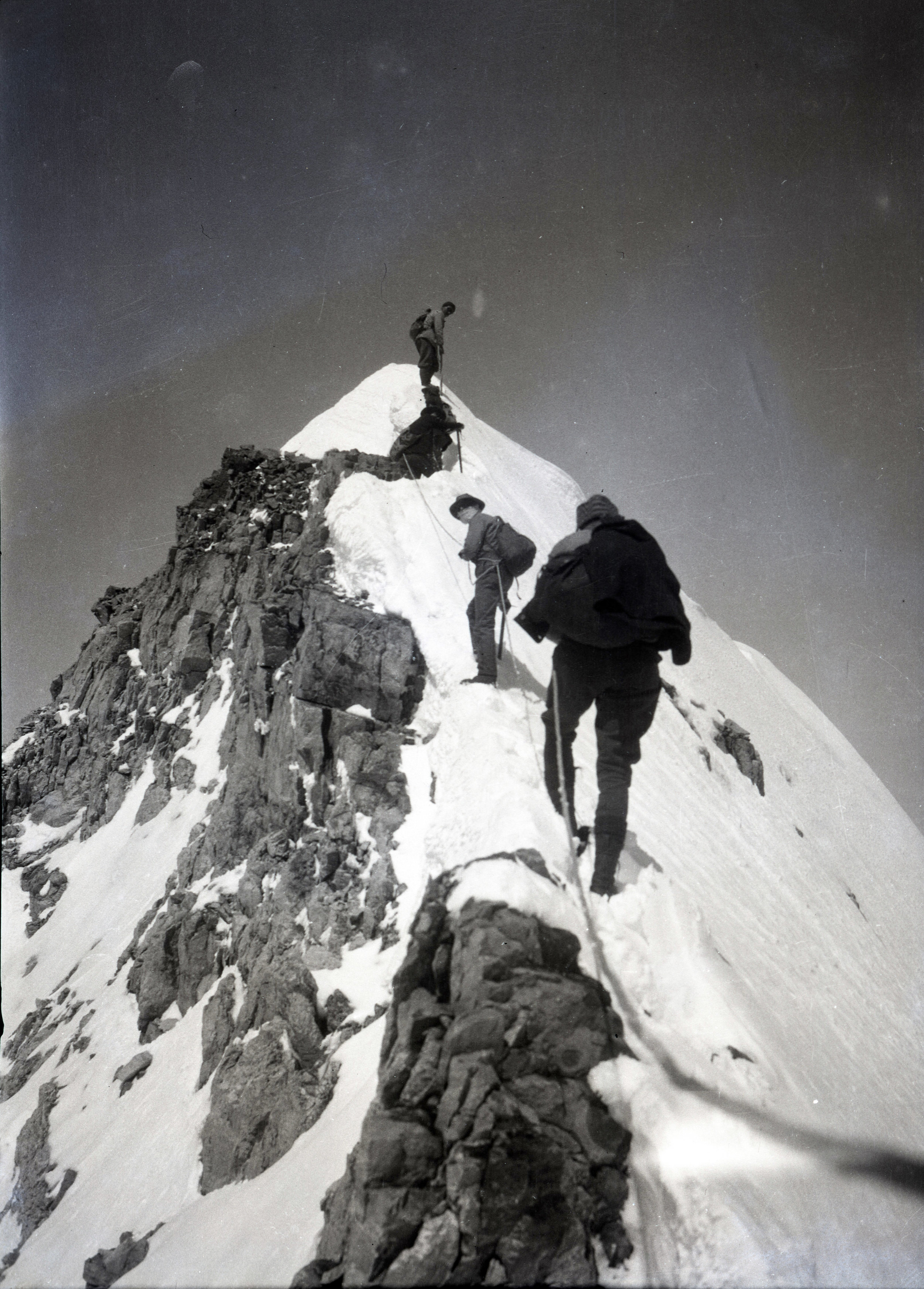

Hobnail boots

in action on Mumm Peak, Canada. 1915

Photo from our Andrew James Gilmour collection.

Boots with linings were not recommended for mountaineering, as the linings were usually made of wool and other natural fibers which were slow to dry when inside a boot. Wet boot linings, either due to water or snow leakage or human sweat, were a major cause of frostbite resulting in the loss of toes.

When not in use, the boots needed to be stuffed with dry paper, hay, straw or oats which were changed at intervals to ensure that all moisture was absorbed. If they weren't stuffed in this manner on an expedition, they were in danger of freezing and twisting out of shape.

A pair of worn hobnail boots set to dry over a fan in about 1920. This luxurious set-up was possible because the mountaineer was staying in a Swiss hotel.

Photo from our Andrew James Gilmour collection.

“Look with suspicion upon the climber who says he wears the same pair of boots without re-soling for three or four years. It will probably be found that his climbing is not of much account, or he is wearing boots which have badly worn and blunted nails, with worn-out and nail-sick soles, a worse climbing crime if he proposes to join your party, than if he were to wander up the Weisshorn alone.”

Crampons

Today crampons are made of stainless steel and weigh about 1 to 2 lbs. They can be bolted or strapped to the boot. In the early 20th century, crampons were made of steel or iron. They were strapped to the boot with hemp or leather straps passed through metal loops attached to the frames. Surprisingly, they didn't weigh too much more in the 1920s than they do today.

They could be bought in a variety of configurations, including models ranging from four to ten spikes. Mountaineers who recommended their use wrote that good crampons should have no fewer than eight spikes which should not be riveted to the frame. The crampons also should not be welded anywhere and the iron variety were likely to break if any real work were required of them.

A steel crampon with eight spikes and hemp and leather straps - ideal!

From the American Alpine Club Library archives

Good footwear is still one of the most important aspects of any trip. We're extremely grateful boot technology has advanced so much.

Care and Handling of Archival Nitrate Negatives

by Allison Albright

Nitrate film base was developed in the 1880s and was the first plasticized film base available commercially. It enabled photographers to take pictures under more diverse conditions, and its flexibility and low cost was partially responsible for making photography affordable and accessible to amateur consumers as well as professionals. It was widely used from the 1890s until the 1950s.

An album of nitrate negatives circa 1900

Nitrate negatives also happen to be mildly toxic and somewhat volatile. Because the material is the same chemical composition as cellulose nitrate (also known as flash paper or guncotton), which is used in munitions and explosives, it is incredibly flammable and prone to auto-ignition. It was also used in motion picture film in the early 20th century and was responsible for several movie theater fires during that era.

Below are some negatives in the early stages of deterioration.

As if the danger of combustion wasn’t enough, nitrate negatives also emit harmful nitric acid gas as they deteriorate, meaning that we need to use safety precautions such as respirators and latex gloves when handling these negatives.

HNO3 + 2 H2SO4 ⇌ NO2+ + H3O+ + 2HSO4

Nitric acid is considered a highly corrosive mineral acid.

Nitrate negatives usually deteriorate in just a few decades, making them an extremely unstable storage medium. As they deteriorate, the image begins to fade and the negative turns soft and gooey, causing it to weld itself to whatever it’s stored with, resulting in the loss of the image.

A clump of badly deteriorated negatives stuck together forever

When good negatives go bad - a negative in the process of becoming goo

Like most archival collections containing materials created from about 1890 to the early 1950s, the AAC’s collection includes some nitrate film negatives. For most of their lives, these negatives have been stored in a cold, temperature controlled area. We’re digitizing these negatives in order to capture the images and make them accessible to the public before we put them in deep freeze. The best way to preserve and store nitrate negatives for the long term is to freeze them to slow the process of deterioration and minimize the risk that they’ll start a fire.

Because of the unstable nature of nitrate negatives, some deterioration is to be expected. However, the vast majority of this collection is still in good shape. We've included a few selections below. Eventually, we’ll make all the images from our nitrate negatives available.

These photographs are taken from the collection of Andrew James Gilmour (1871-1941), an AAC member whose surviving photographs help inform our knowledge of the history of climbing and what the sport was like in the early 20th century.

Magic Lantern Slides

A Lantern Slide Close-Up. Caption reads: Climbing Mt. Lyell, Yosemite Nat. Pk. (Photo by Farquar). This slide came from Francis P. Farquhar. It is probably from the 1910-20s.

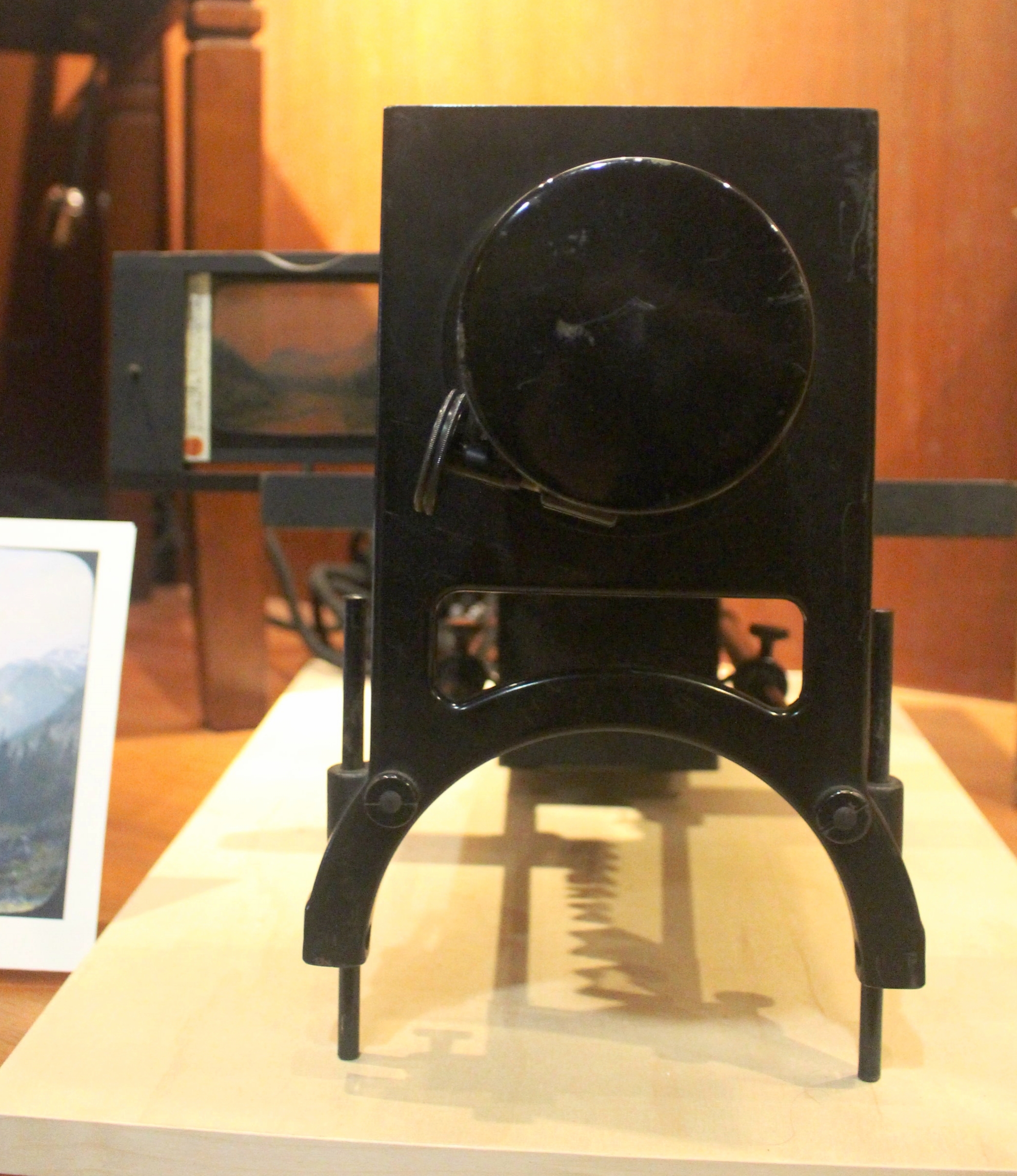

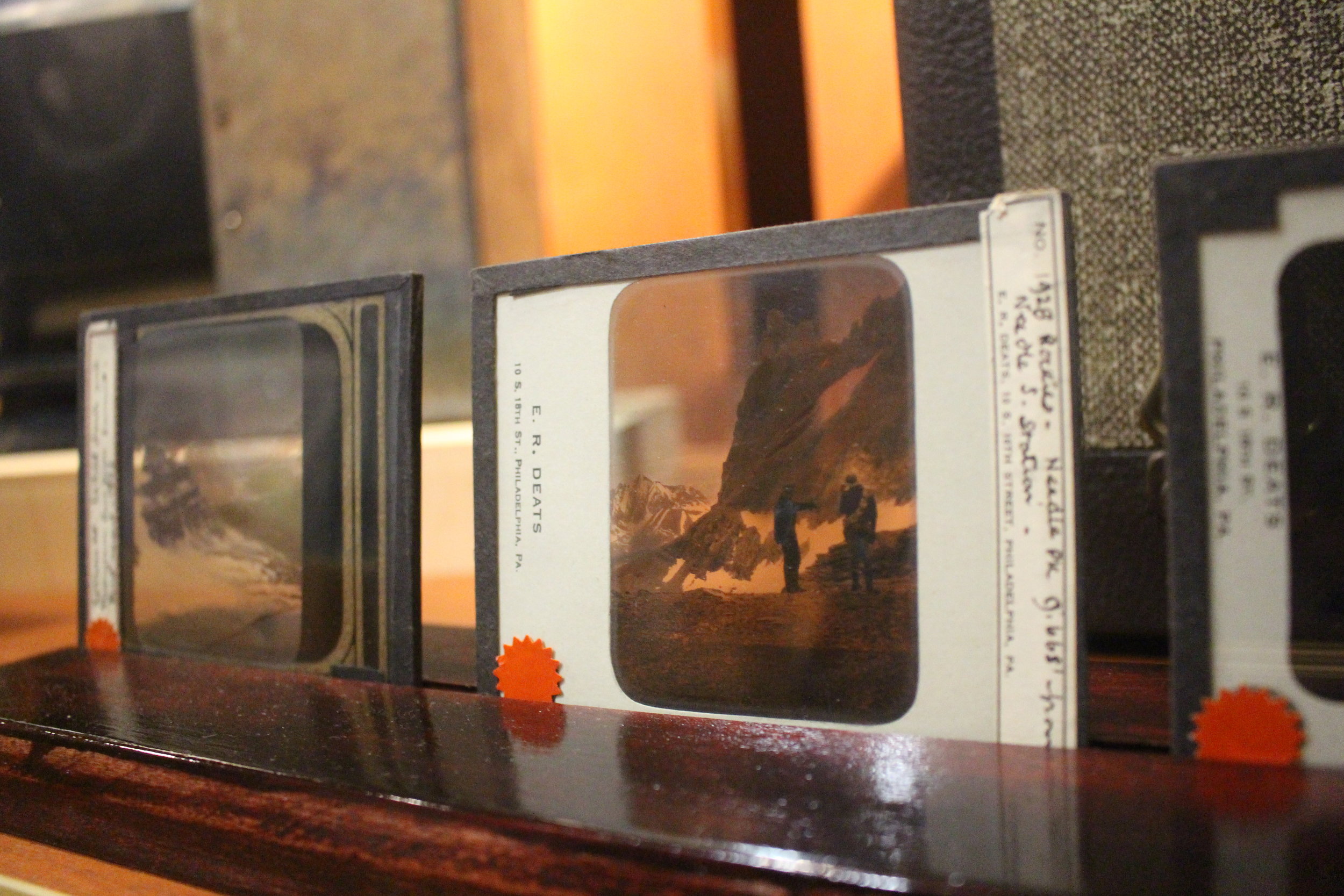

The magic lantern was an early type of image projection, used since the 17th century, to show painted or printed materials for entertainment. With the invention of the photograph, it was adapted in the 19th century to project photographic materials to the masses.

Mountaineers would often employ this method to illustrate lectures on their mountain pursuits. Many of the early American Alpine Club annual dinners included lectures and talks that were "illustrated by lantern views."

Excerpt from the 1911 By-Laws & Register Book: Notes from the Eighth Annual Meeting held in Boston, 1909

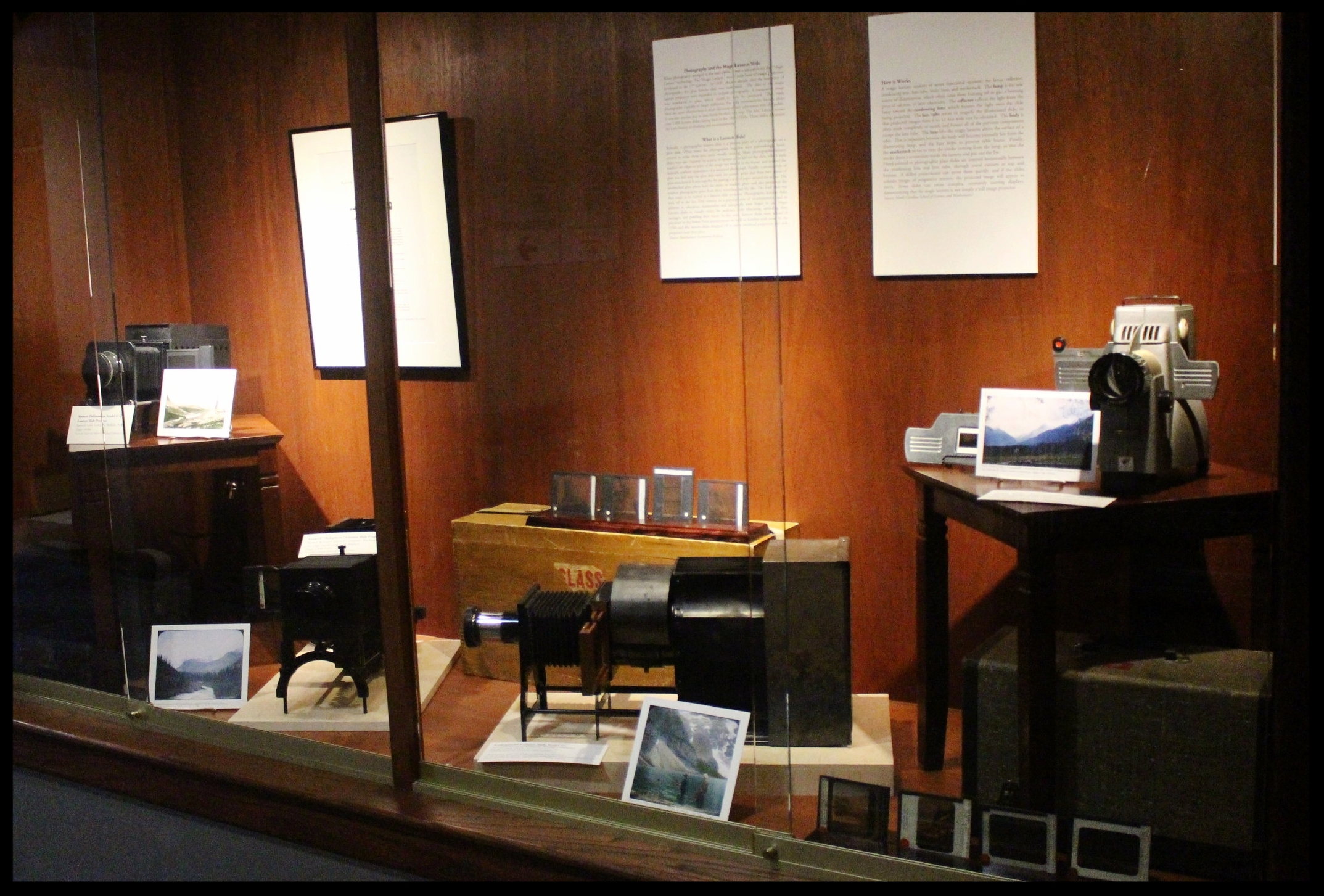

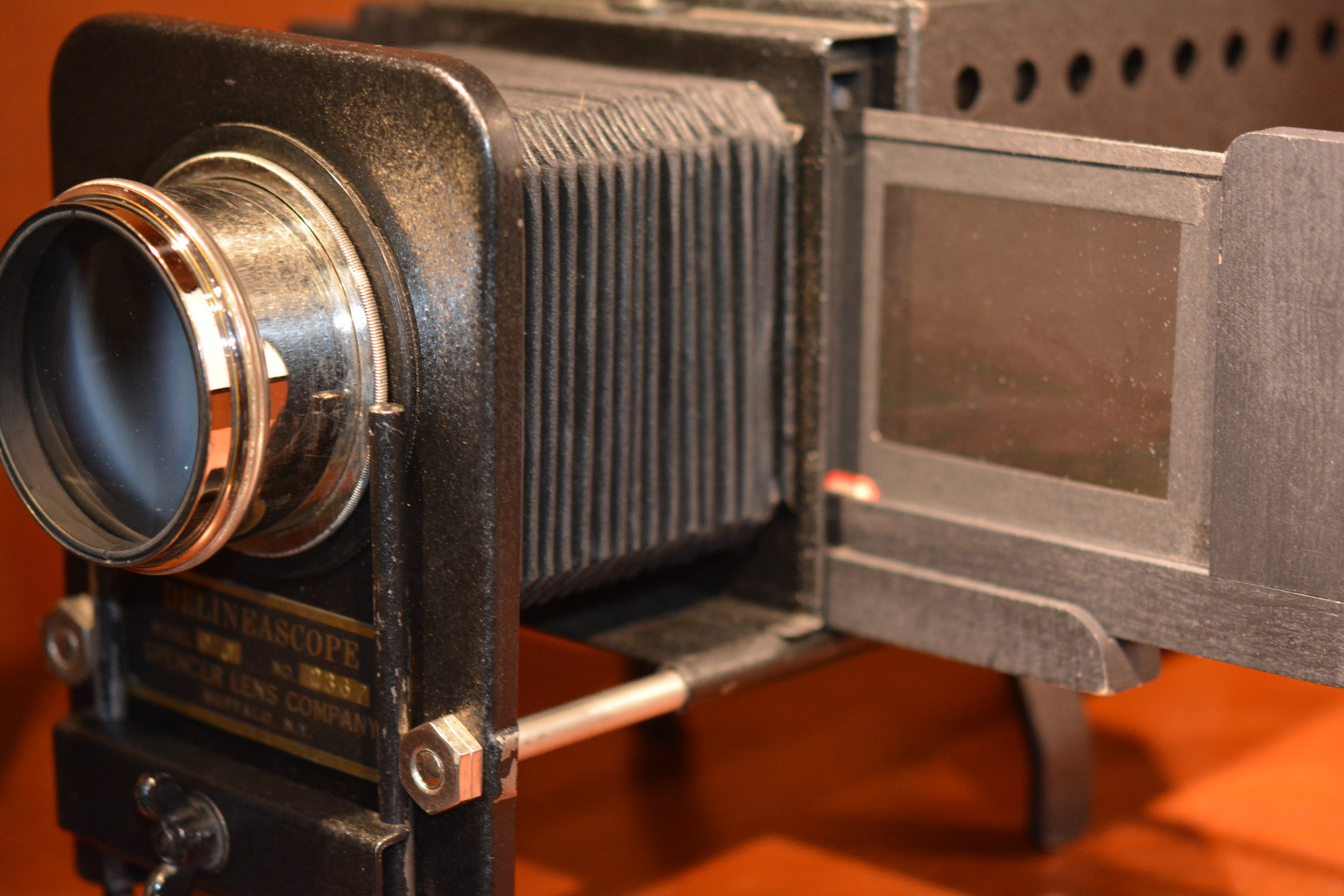

Lantern slide projectors are the apparatus used to display the images. We have three in the AAC Library. They are currently on exhibit (until February 2018) in the American Mountaineering Center.

On display at the American Mountaineering Center in Golden, Colorado (until Feb. 2018).

These projectors date from approximately 1900 to 1930s. A 1950s slide projector is also on display with a 35mm glass slide. The many glass lantern slides on display date from 1890-1950. Most are from the American Alpine Club Archives, with a few from the Colorado Mountain Club Archives. You can see mountain scenes, cabins, and instructional slides.

This is one of the projectors in our collection. This page is from a 1911 Bausch & Lomb catalog, which can be viewed in its entirety here on HathiTrust.