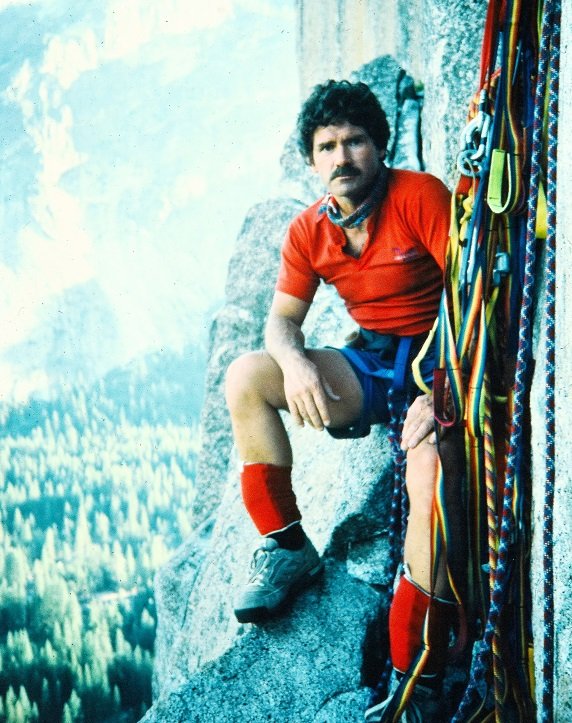

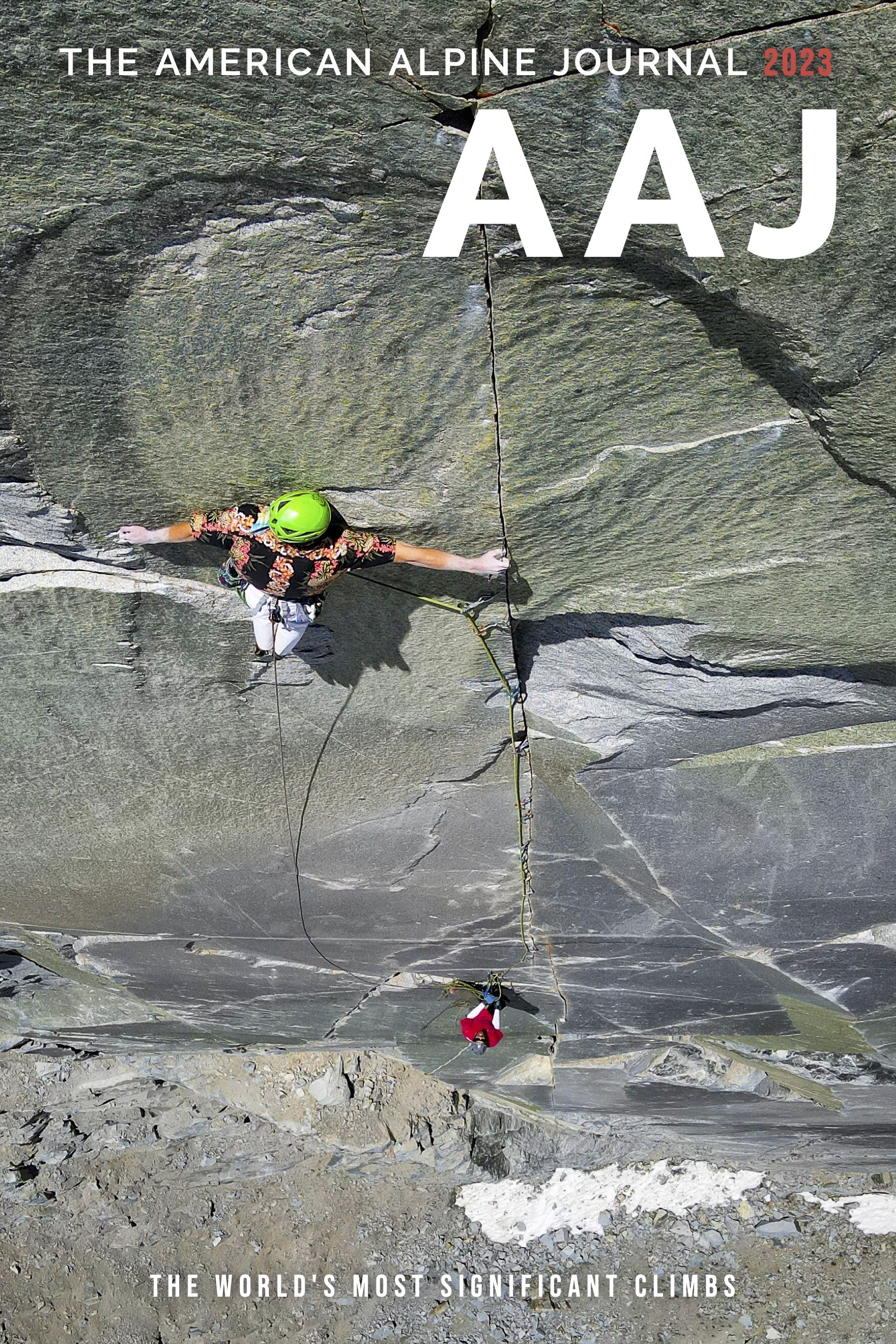

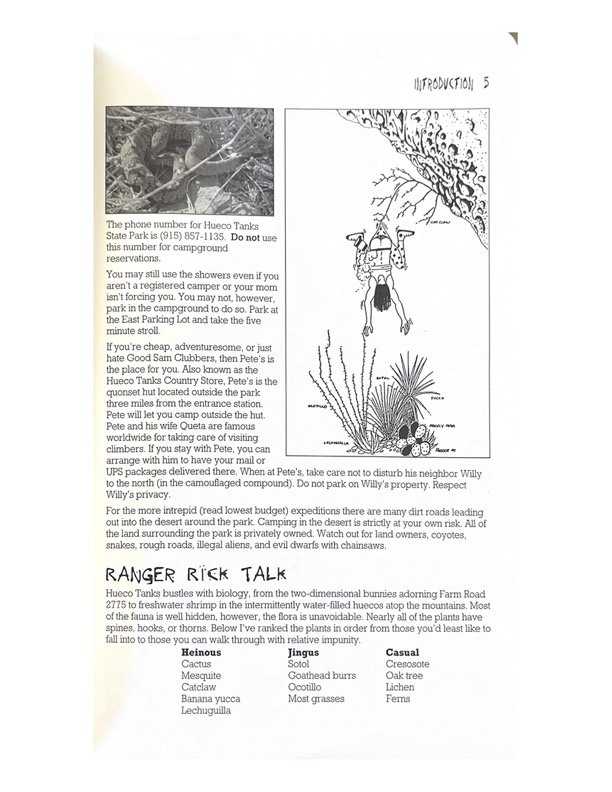

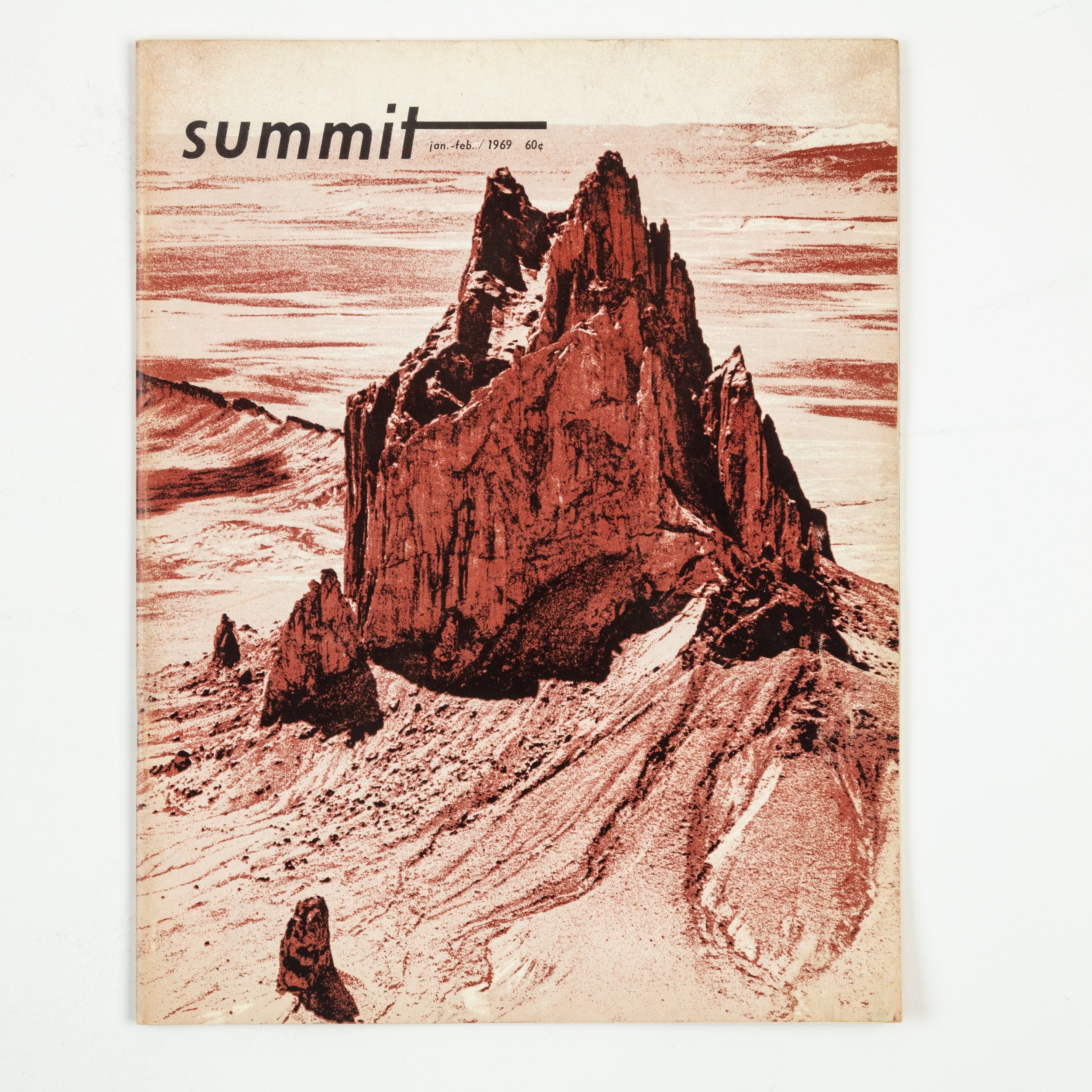

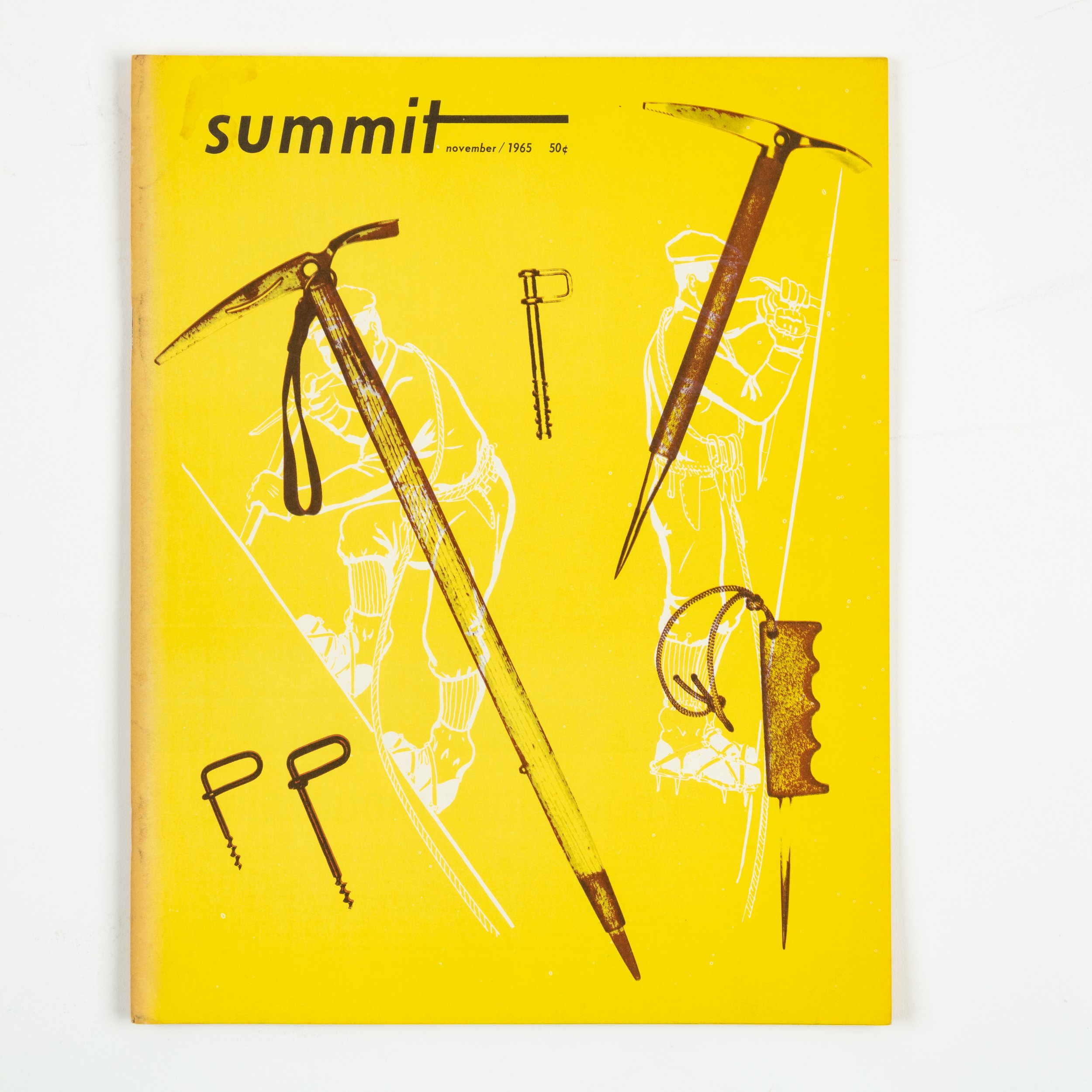

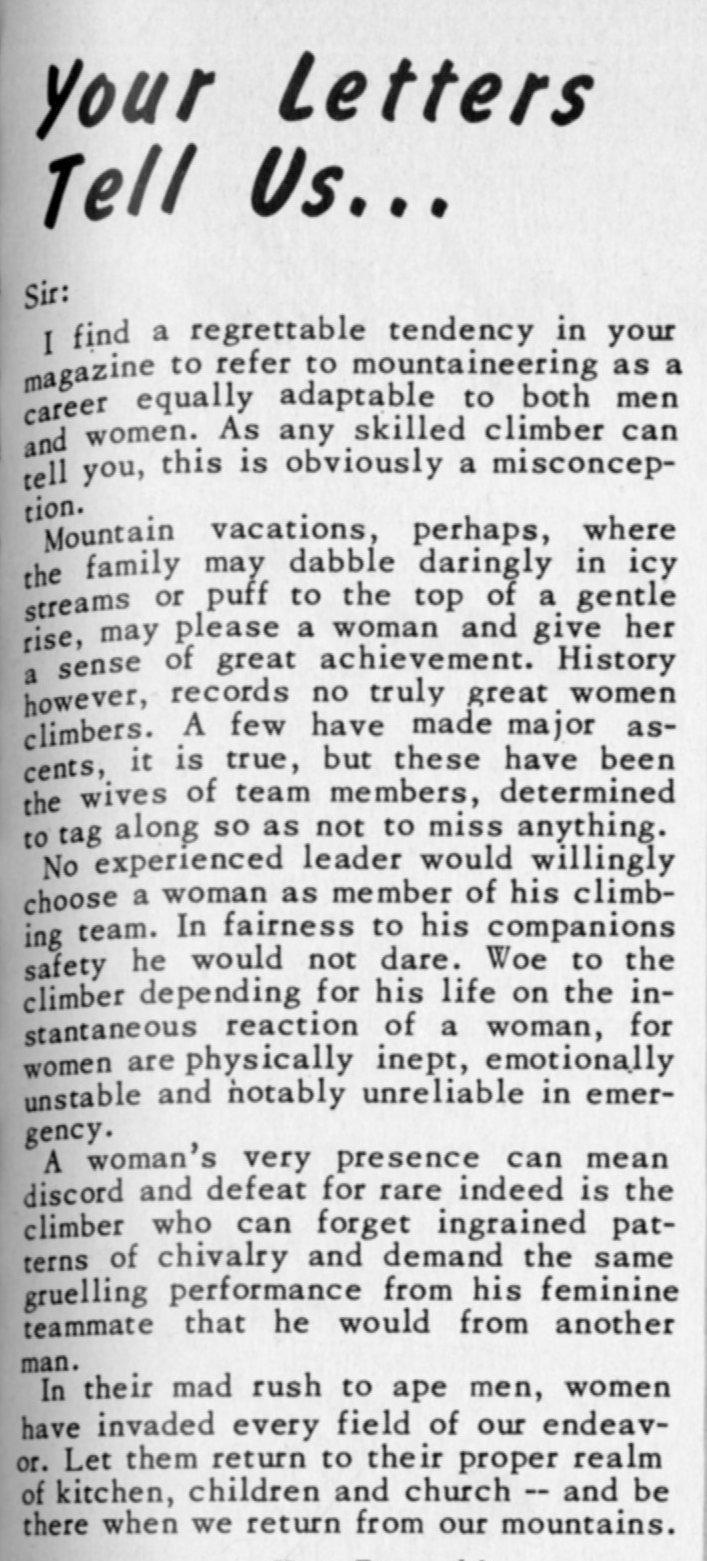

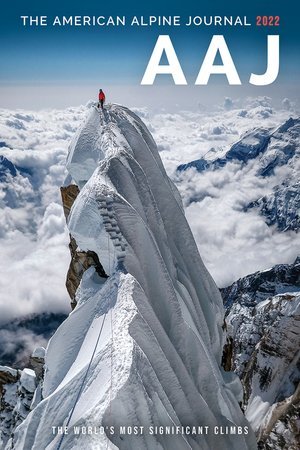

Catalina Shirley Climbing in Ouray. PC: AAC Member Nicholas Moline

By: Sierra McGivney

Ice cascades into the Uncompahgre Gorge, creating an ice climber's paradise. With more than 150 manmade ice and mixed climbs across almost 2 miles of terrain, Ouray Ice Park is an ice climbing playground, and the Ouray Ice Festival is the ultimate celebration of that. This year, the ice fest kicked off on Thursday, January 18, with a Barbie pool party and lasted through the weekend. Pros and ice climbing connoisseurs taught clinics, pushed grades, and had fun, but Ouray is also often the first and only time rock climbers try ice climbing. All types of clinics are offered, demo gear is included in an all-access pass, and volunteers belay at the walk-up wall, making the Ouray Ice Festival an accessible entrance to the sport.

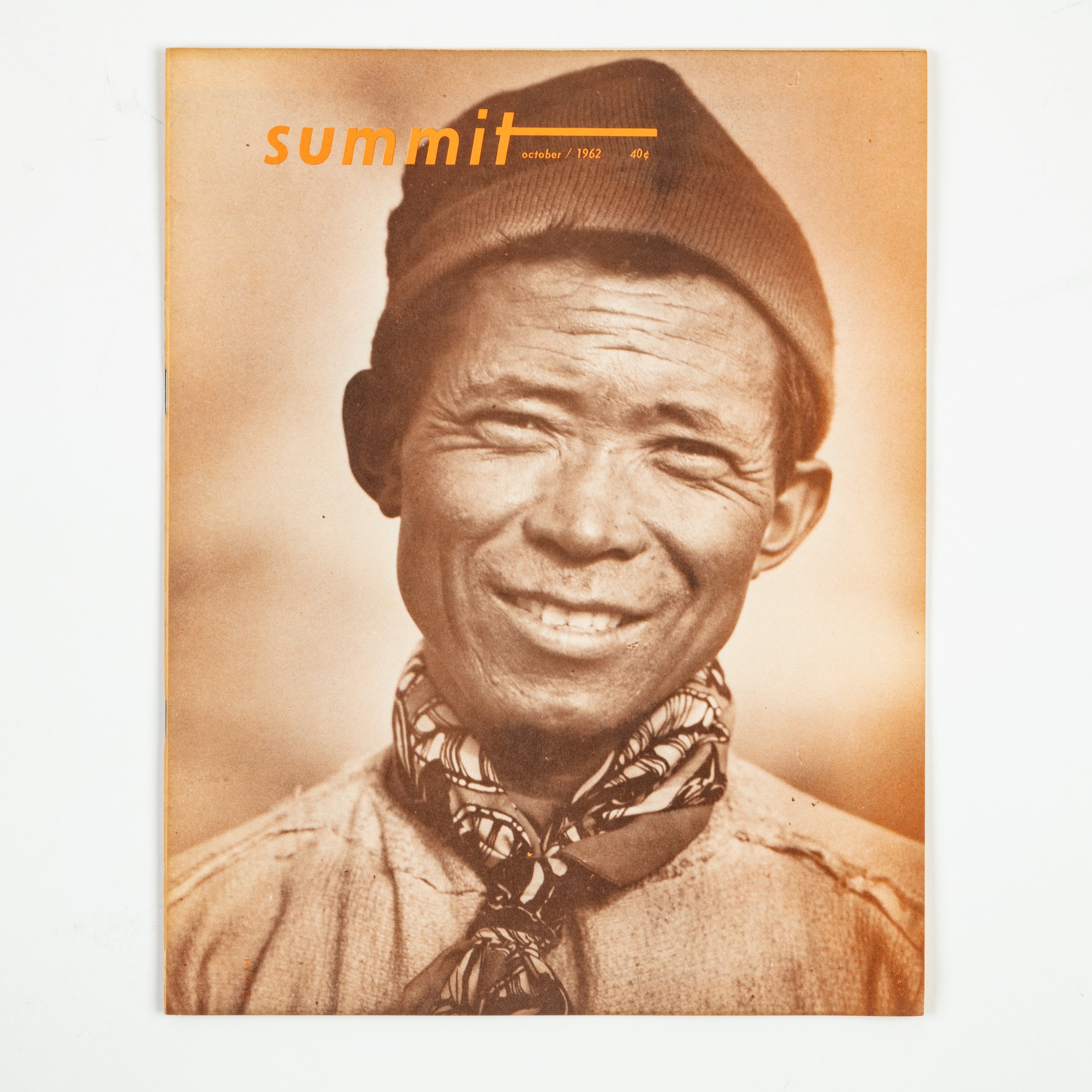

That's precisely how Ian Umstead, now a USA Ice Climbing Team athlete, tried ice climbing for the first time two years ago. He originally wasn't sold on ice climbing. He had fun but thought it was sketchy. But something clicked when a friend invited him to go dry tool at a local crag in March 2023.

"It's like sport climbing with a little extra spice," said Umstead.

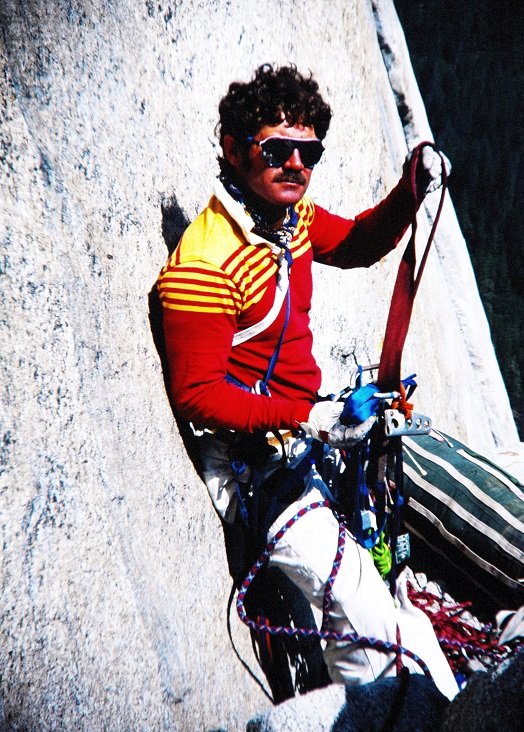

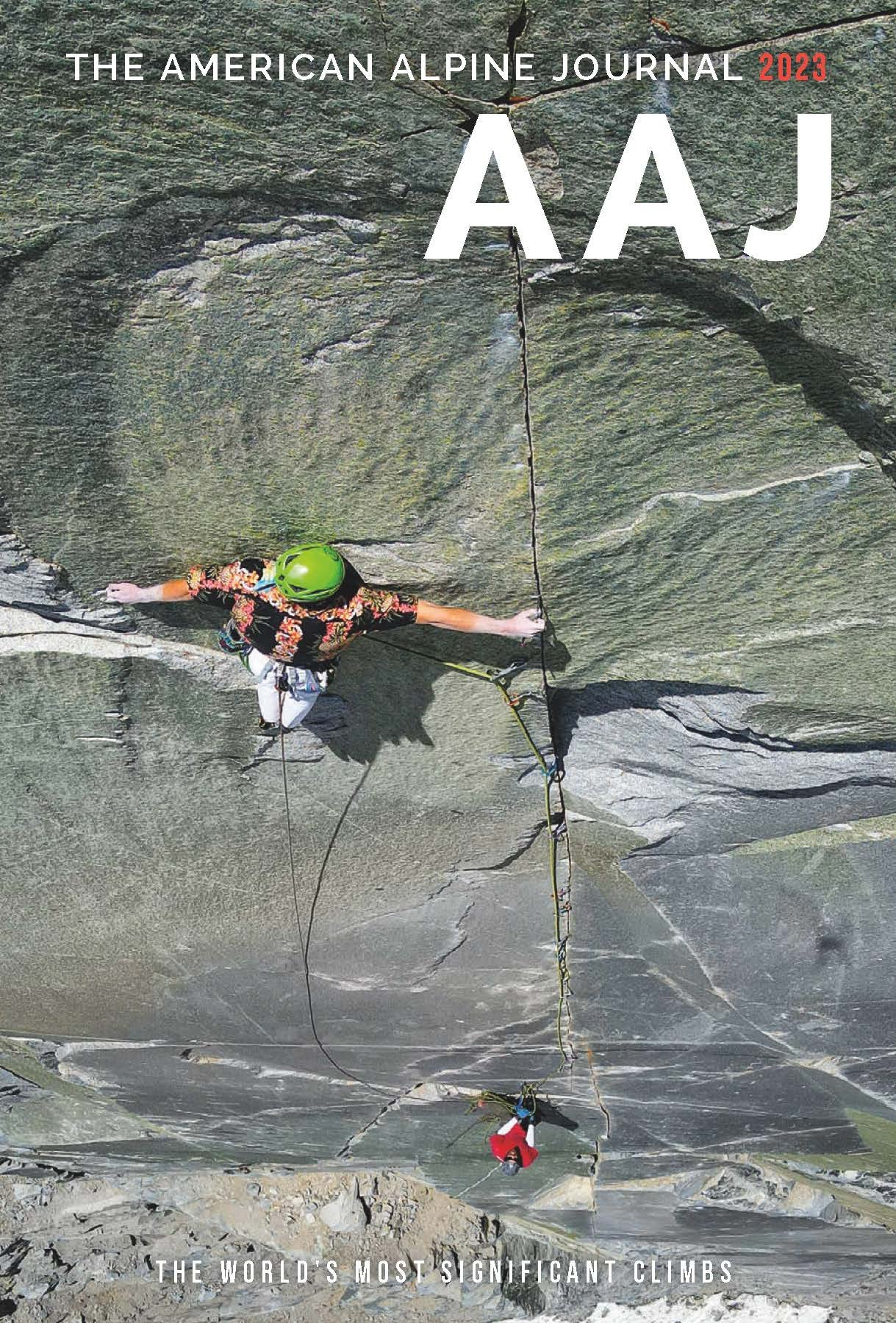

Ian Umstead Climbing in Korea. PC: Provided by the UIAA

Umstead is primarily a sport climber, so he had strength built up from sport climbing that translated into dry tooling. A couple of athletes on the Ice Team encouraged him to try out for the team even though he had only been dry tooling for three months. Umstead was surprised they suggested it but thought: If I'm going to do this, I'm going to do it right. So, he put off his sport project and trained on tools for eight weeks. Then, he went to tryouts and made the team. He was stoked. Umstead returned to training for his sport project, and after five weeks, he sent his first 5.14. Umstead has a semi-professional bike racing background, so he eats and breathes training and competing.

"I'm a projecter's projecter," said Umstead.

He picks challenging projects, trains, and tries hard. Drytooling fulfills that, adding an element of goofiness. The movements feel silly and fun and keep Umstead engaged.

Umstead is one of many athletes who started in Ouray. Connor Bailey first tried ice climbing in Ouray at eight years old. He remembers his crampons falling off because his boots were too small, but he liked it. Scratch Pad, a dry tooling gym in Salt Lake City, contacted his climbing team and asked if anyone wanted to try out for the youth ice climbing team. He and one of his friends, Landors Gaydosh, decided to check it out.

"I thought it was going to be just ice climbing," said Bailey. "I was pretty excited. I went in there and saw all the different holds and was like—huh?"

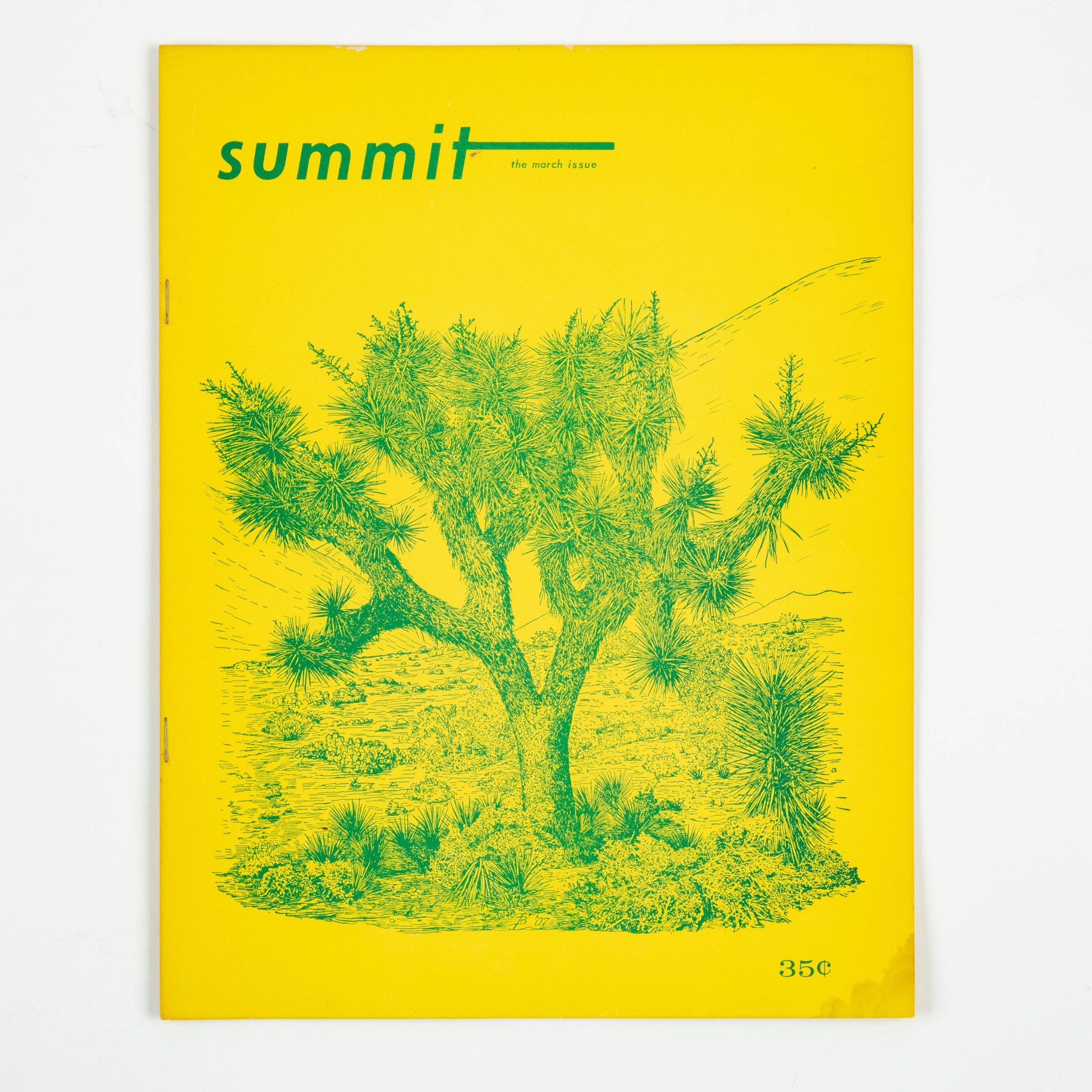

Left to right USA Ice Team Athlete’s Connor Bailey, Tyler Kempney, Mathius Olsen. PC: Provided by Stephanie Olsen.

The holds and movements were similar enough to rock climbing that Bailey found success. Initially, the comps had no age requirements, so he could join the team and compete. Unfortunately, this past year, the youth age requirements changed, and Bailey, who is 12, falls below the youth age requirements. Thankfully, he could still compete in Ouray.

Bailey sometimes questions why he chose this sport, especially when it's cold, but once he begins swinging his tools and warms up, he loves each movement.

From the snow-covered bridge leading into the vendor village, the giant competition wall rises up from the gorge. Starting from the bottom of the gorge, competitiors climb on rock and ice, until they reach the artificial wall, where they begin placing their tools on holds made of various materials. The Ouray Ice Festival is a crucial competition for the USA Ice Climbing athletes as part of the UIAA Continental Cup Series. On the Saturday of the festival, commentators and spectators gather, and above the din of music playing, people cheer on the competitors in the finals.

Catalina Shirley began her climbing career young—like most of us do—climbing trees and doorways, scaring the sh*t out of our parents. When Shirley began venturing to the roof of her parents' house, her mom drew the line and signed her up for summer camp. Shortly after, her family moved to Durango, Colorado, where she joined Marcus Garcia's team. Garcia was working on building out the USA Ice Climbing Youth team. Shirley began training and went on to compete in France the following year when she was fourteen.

"I love the kinds of moves that you can do in ice climbing that you can't quite get in rock climbing—like the crazy floating underclings and gastons and, of course, figure fours and anything on swinging features," said Shirley.

Shirley likes the thought required for every move and the freedom of movement in dry tooling. Climbers can put their feet anywhere, regardless of body size or strength. But in Ouray, the competition wall reminds Shirley of a puzzle, with only one right way to solve it. Part of that puzzle in the Ouray Finals was a dyno. Shirley set up for it, looking out at the crowd. Then she jumped and closed her eyes, landing slightly above the hold but sticking it. When she opened her eyes, everyone screamed, infusing her with energy. With one minute left on the clock, she went as fast as she could, letting the crowd's energy flow into her. She placed first in the women's lead competition.

"I feel like I perform the best when I'm under a little bit of pressure," said Shirley.

Catalina Shirley Climbing. PC: AAC Member Nicholas Moline

The weekend before, January 12 through 14, Shirley placed second in both lead and speed in Cheongsong, Korea. She is the first American to make the lead podium—man or woman. The competition setting is her style: long figure fours, roof climbing, and endurance-based; climbing fast is one of her strong suits. She got to the top of both qualifier routes. She was one of three women to do so, next to Marianna Van Der Steen and Woonseon Shin, both of whom Shirley had been watching since she was a kid.

But in the Cheongsong finals, Shirley had fallen three moves from the top because she missed the dyno. Sticking the dyno in Ouray means that much more. She credits her team as a big reason why she made the podium. They provided support for her all weekend, from food to encouragement. Her team had her back.

"It really felt like the whole team's medal," said Shirley.

Shirley believes there are four main challenges to competitive ice climbing: strength, problem-solving, fear of falling, and fear of failing. It's what keeps bringing her back. In "regular" life, rarely are all those elements compounded.

"Overcoming all of that is the best feeling in the world," said Shirley.

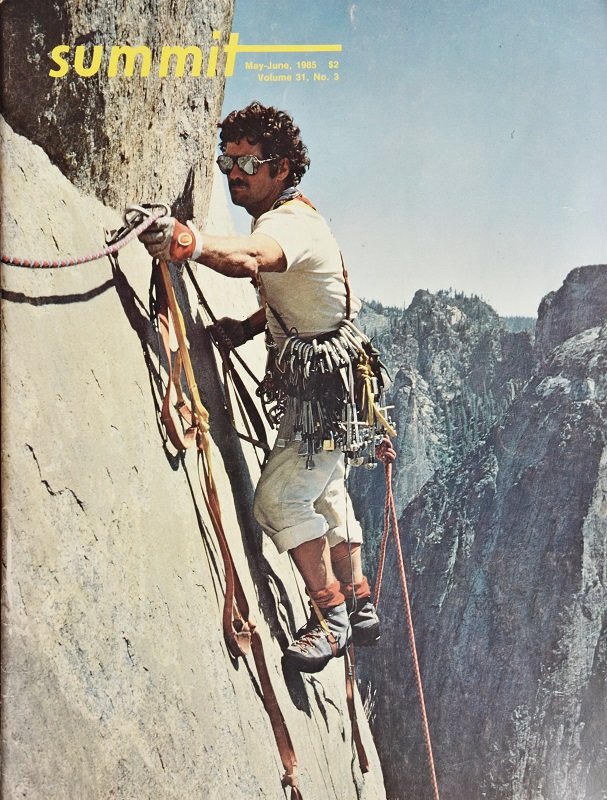

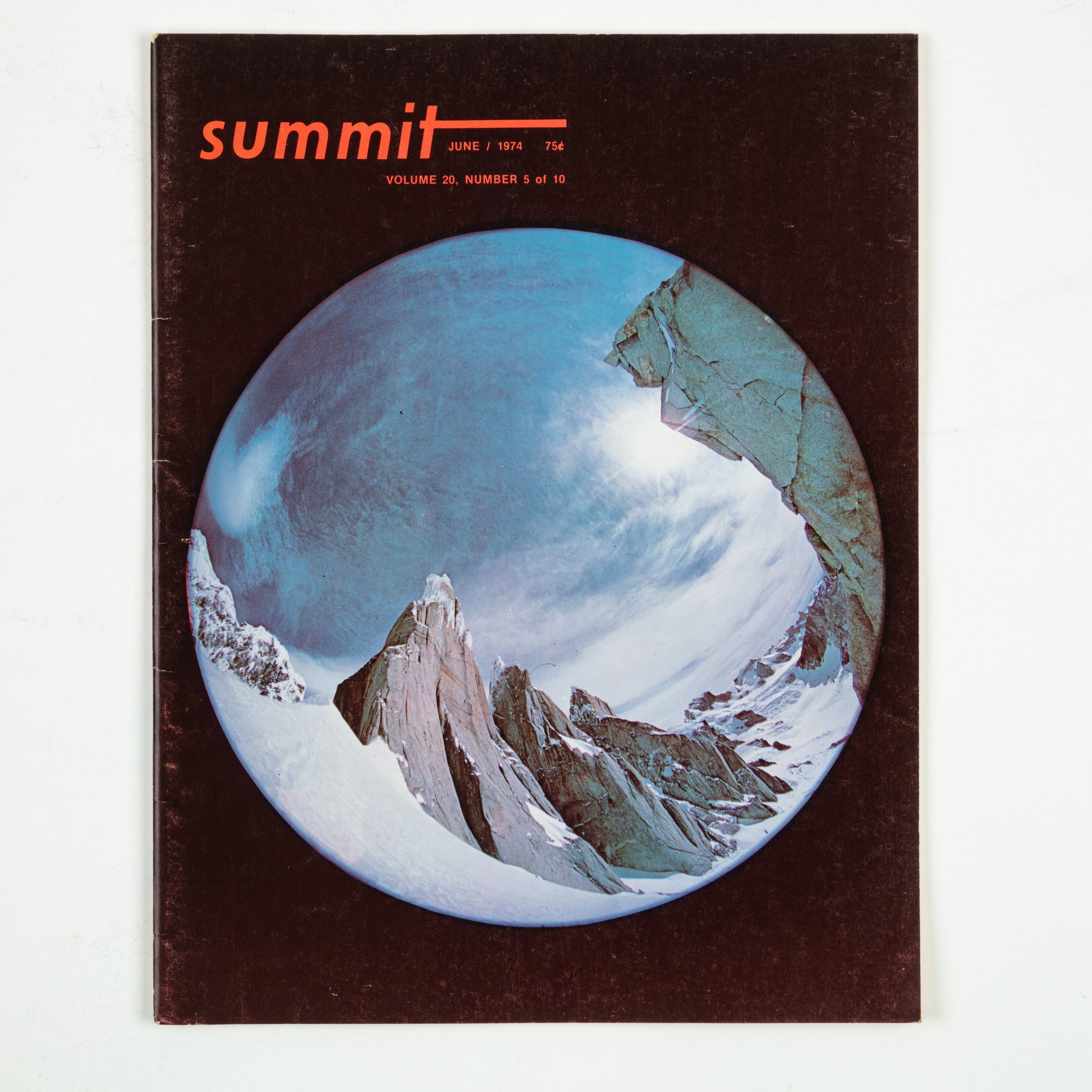

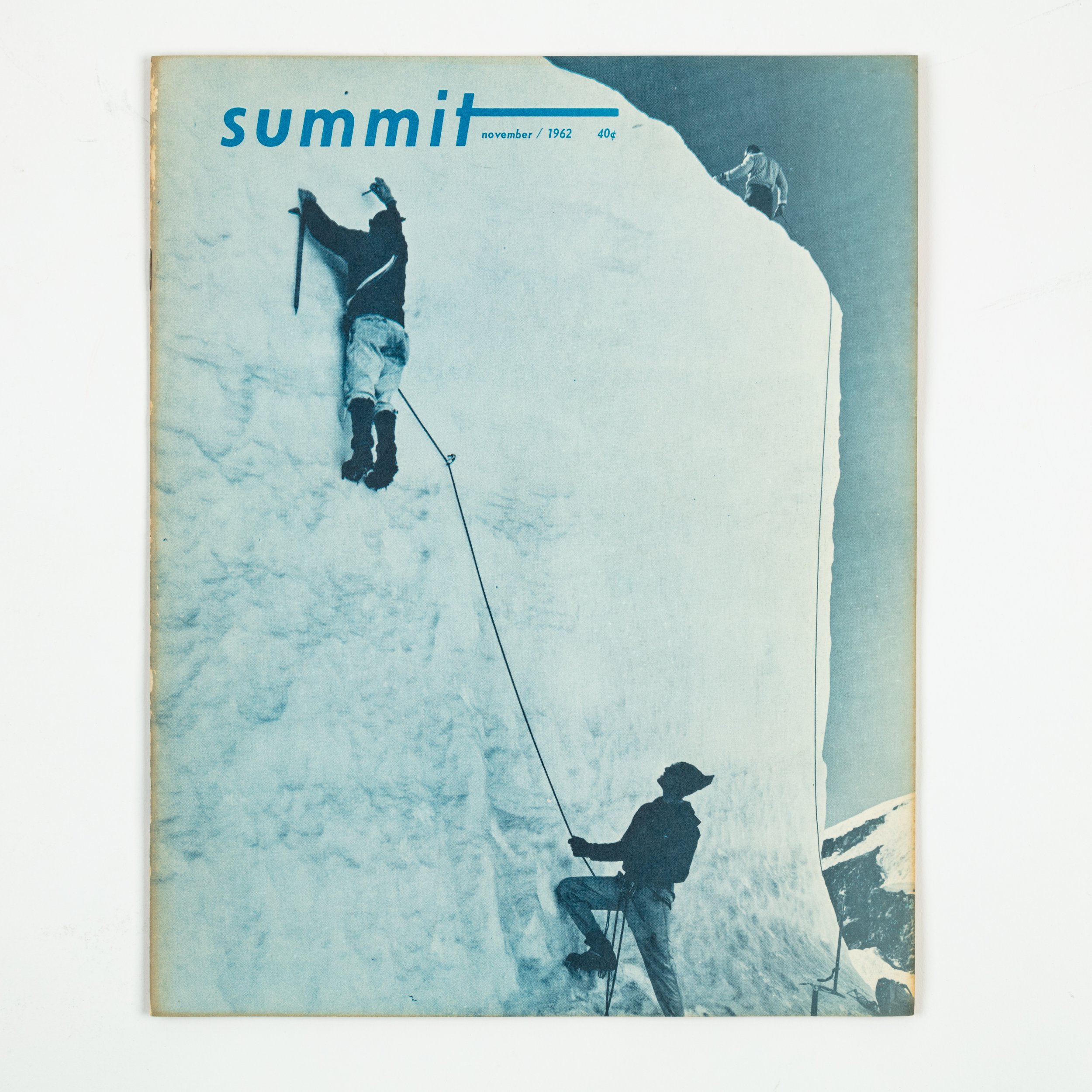

Sam Serra Climbing. PC: AAC Member Nicholas Moline

Each person on the USA Ice Climbing Team has their own story.

Sam Serra attended an intro to ice climbing class hosted by the Ice Coop in August 2021. Tyler Kempney was teaching it and asked if anyone wanted to try dry tooling. Serra had a blast.

"I went to get into ice climbing, but I feel like I really got into dry tooling," said Serra.

He didn't get on ice until two months later. As Serra spent more time at the Ice Coop, he got dragged into competing. His first competition was in Michigan, only a couple of months after he began climbing. It wasn't his strongest competition, but he found climbers he wanted to surround himself with. The community kept him around until he learned to like dry tooling competitions. Serra grew to love the movement and style of competition dry tooling. The unique way of using your ice tools pushes the climber to be creative in a way that differs from traditional ice climbing.

Sam Serra being lowered. PC: AAC Member Nicholas Moline

"When It comes to dry tooling and really competition style dry tooling–it just opens the door to so many new movement patterns that they don't even exist outside–they almost can't exist outside," said Serra.

Phoebe Gabrielle Tourtellotte's story looks a little different. Tourtellotte had to drop out of speed climbing due to a joint condition in the fall of 2021. She felt aimless. At the time, she lived across from the Ice Coop in Boulder. Her boyfriend encouraged her to try that dry tooling thing. Despite inner doubts about how she would look or perform, she went.

In the first couple of months that she was learning to dry tool, she had to confront why she was still climbing at all after speed climbing hadn't worked out. Then it hit her: here was an opportunity to start over.

"It's so cool getting to learn all new stuff," said Tourtellotte, "There are so many tiny nuances I never would have expected to learn about in this sport."

She had gone from one of the fastest disciplines to one of the slowest and methodical. Coming from a speed-climbing background, Tourtellotte moves more dynamically. At the Ice Coop, she gets beta and technique spray-downs from everyone in the gym. Her teammates are open to mentoring each other, even if they're competitors.

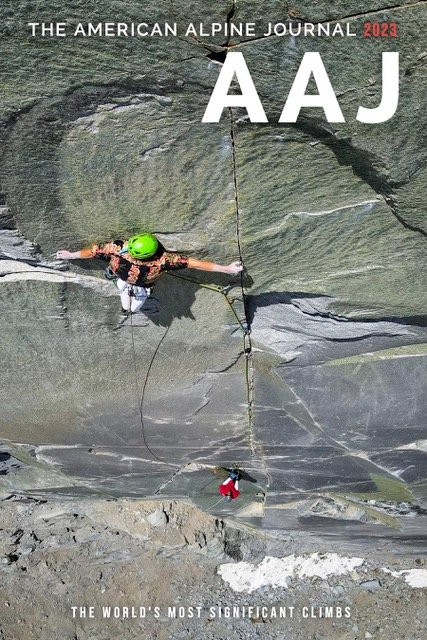

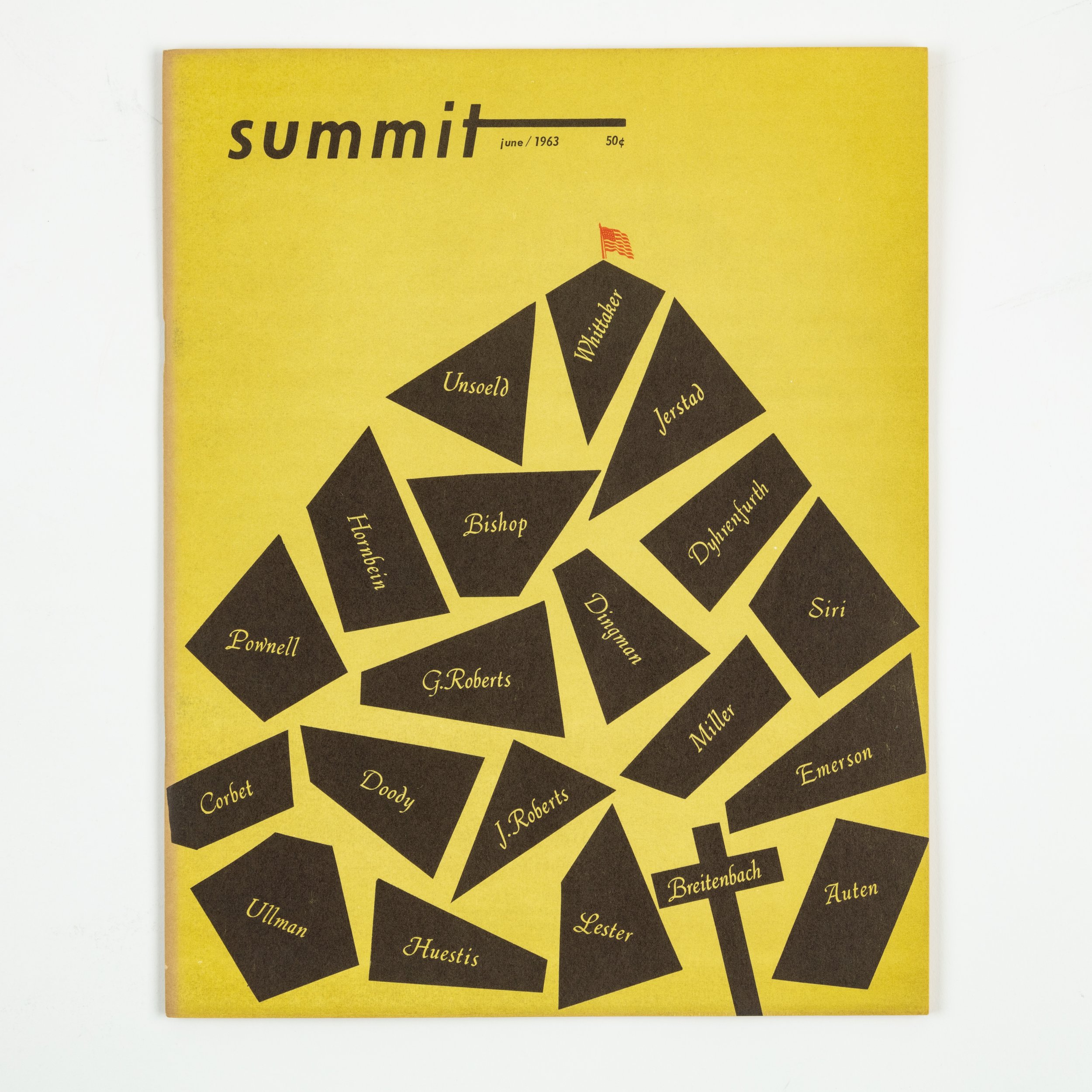

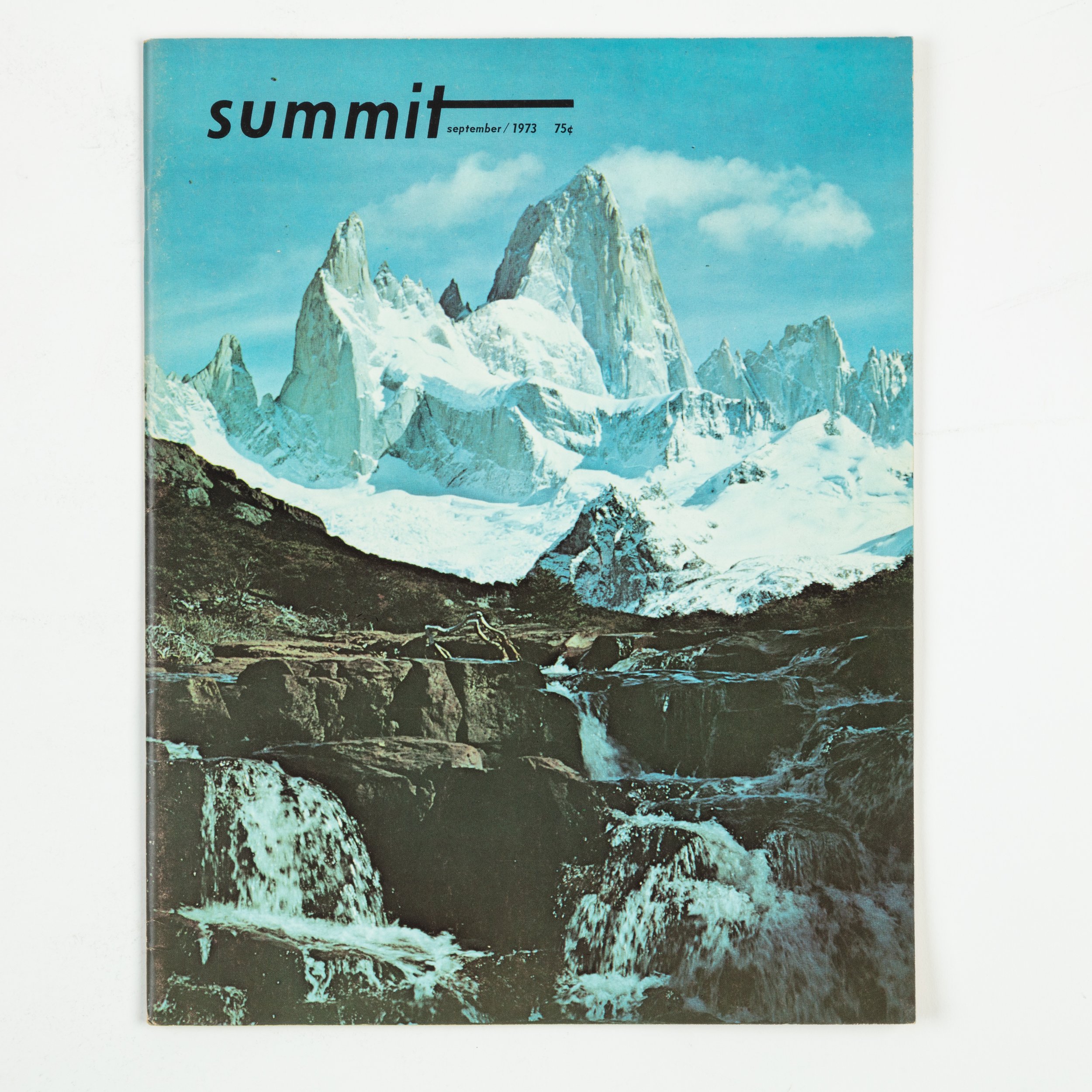

The USA Ice Climbing Team in Cheongsong, Korea. Provided by the UIAA

The small community of competition ice climbing supports and uplifts one another. It brings together people of all ages and backgrounds, connected through their niche passion for ice climbing and dry tooling. The team will continue to swing tools, compete, and celebrate their love of climbing through silly and unique movements.

Ouray Ice Fest Results

Catalina Shirley placed first in the Women's lead final, with Corey Buhay in Third. Tyler Kempney placed first in the men's lead final, with Sam Serra placing second. They both topped the finals route. The Ouray Ice Festival competition is a special place for the team, for everyone to gather and celebrate. The USA Ice Climbing team will end their season at the World Championships In Edmonton on February 16 through 18. Tune in to the UIAA YouTube channel to livestream the event and support the USA Ice Climbing Team.

UIAA Ice Climbing Continental Open - Ouray, USA: Top Three

The Women's Lead Final

1 Shirley, Catalina USA 1 [1] 1 [36.100]

2 Louzecka, Aneta CZE 4 [12.0] 2 [31.000]

3 Buhay, Corey USA 3 [9.0] 3 [28.100]

The Men's Lead Final

1 Kempney, Tyler USA 1 [1] 1 [TOP (0:00)]

2 Serra, Samuel USA 2 [4] 2 [TOP (0:00)]

3 Howe, Tyler CAN 3 [15] 3 [33.000]