Shiprock (Tsé Bit a í, “winged rock”) rises over 1,500 feet above the desert floor of the Navajo Nation in San Juan County, New Mexico (Diné, Pueblos, Ute lands). Shiprock was a sought-after summit during the late 1930s, until the first ascent was done in 1939 by David Brower and Sierra Club team. It marks one of the first times bolts were placed for protection in the history of North American climbing. However, the rock formation is highly sacred to the Navajo people, having historical and religious significance. In 1966, the Navajo Nation banned all climbing on their lands, including Shiprock.

by Aaron Mike

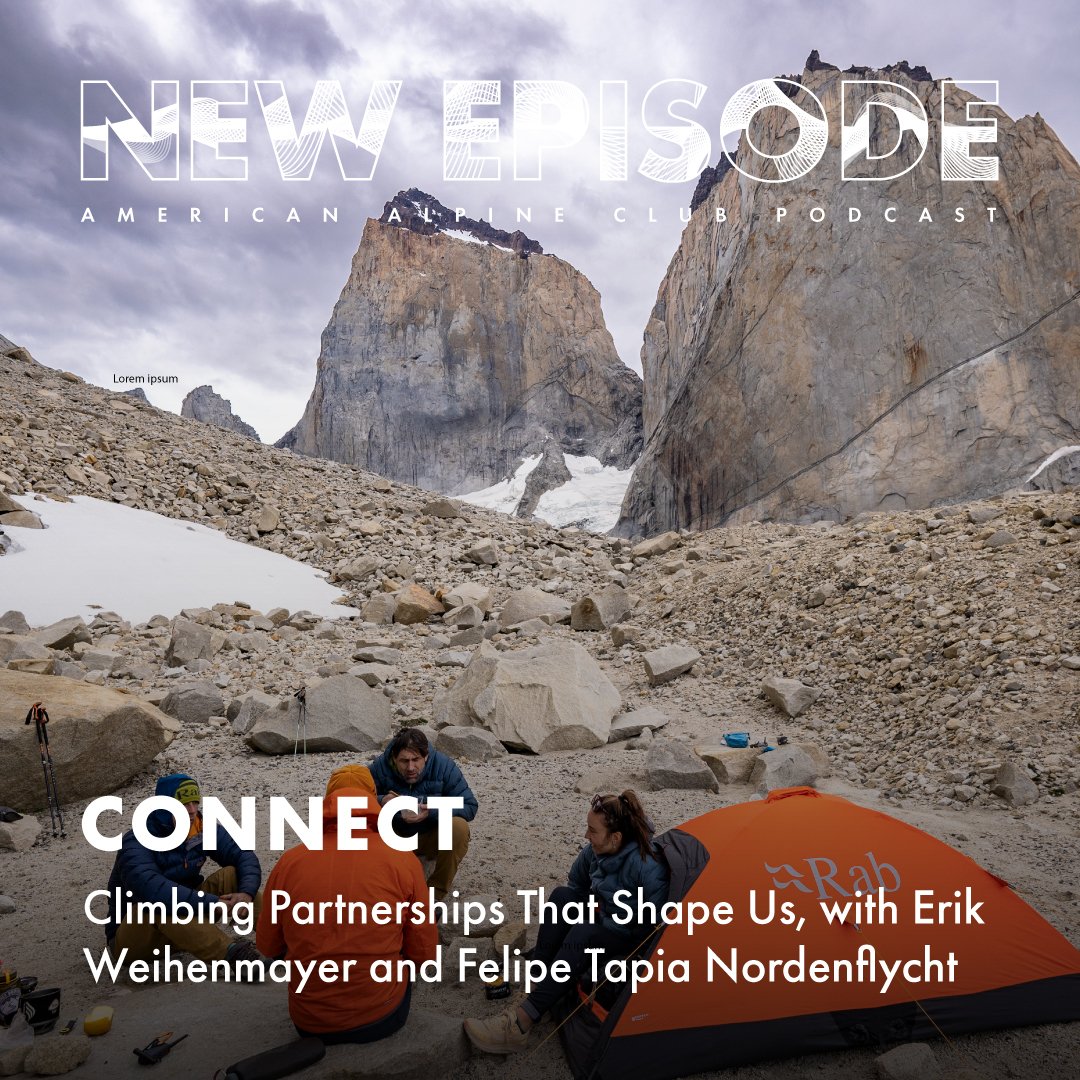

This Indigenous People’s Day, we’re reposting a beautifully written essay by Navajo climber Aaron Mike that we published in 2019.

Acknowledging the roots and conceptualizations of the outdoor activities that we so passionately pursue enriches our participation and ties us to the land, as well as to one another. When we view our industry through a historical lens, we inevitably hear about John Muir, Sir Edmund Hillary, Royal Robbins, and other giants of outdoor recreation. We revere them based on their successes and physical accomplishments. There is one similarity between them that is rarely mentioned: the entirety of their recreational pursuits took place on ancestral homelands of Indigenous Peoples. The Miwok and Piute resided amongst the majestic granite walls of what is now Yosemite National Park. The Havasupai and Hualapai cultivated the areas of the Grand Canyon. The Shoshone, Bannock, Blackfoot, Crow, Flathead, Gros Ventre, and the Nez Perce tribes inhabited what is now Grand Teton National Park. The history and heritage of Indigenous peoples as an inherent part of the lands on which we recreate is a topic that must be part of the conversation if we are to achieve a responsible, sustainable, and inclusive industry. Especially today, this topic is paramount not only because it enhances the care and stewardship of the lands we all love, but also because it is a statement against the systematic dehumanization of a people.

Diné Bahane’, the Navajo creation story, tells of the journey through three worlds to the fourth world, where the Navajo people now reside. The story details chaos and drama as the Diné, or “Holy people,” moved through Black World, which contained no light; Blue World, which contained light; and Yellow World, which contained great rivers. Eventually, in the 4th world, White World, the Diné would assume human form after gaining greater intelligence and awareness. Through these worlds deities, vegetation, and animals accompanied the Diné, as well as our four sacred mountains; Sis Naajini (Blanca Peak), Tsoodził (Mount Taylor), Dook’o’oosłid (the San Francisco Peaks) and Dibé Nitsaa (Mount Hesperus).

Like the story of my people, my tribe, I have gone through many different worlds to walk the path that I am on today. My first world, Ni’hodiłhił, consisted of a surreal state of constantly spending time in the outdoors on the Navajo Nation from Sanders, AZ to Monument Valley, AZ, as well as my hometown of Gallup, NM. Weekends and summers were spent playing with my cousins through the tranquility provided, or turbulence imposed, by our Mother Nature. My grandparents taught me about sheep herding with blue heelers, building hogáns, and butchering sheep. I learned how to take care of horses and cattle, and how to live off of the land. During the spring and summer I spent nights sleeping under the stars and a Pendleton blanket in the back of my grandfather’s early 1990’s Ford F-150. During the fall and winter, I woke up sweating under a sheep woolskin blanket next to a wood burning stove that my grandfather had installed.

I blinked my eyes and I was in the second world of my journey, Ni’hodootł’izh, far from the Navajo Nation in the Northwest, transported to an environment where all of those activities that had made me feel so real were not customary or necessary, and were even frowned upon. Due to my Diné heritage and my personality, being in the outdoors is a necessity. It is hardwired into my entire being. In this second world, the connection to the land that I had experienced and loved was diverted and diminished. I began to feel disconnected from my Diné roots and felt a growing spiritual void.

I awoke for my first day in a new desert environment and into my third world, Ni’haltsoh. By this time, high school, my identity was in constant flux. I struggled to find my place and individual path in a sea of foreign values and ambitions. I blew through various sports, political ideas, social scenes, and academic areas of study. Amidst the chaos of these years, I found a vehicle that would take me into my fourth world, rock climbing. Being on the walls and boulders in Yosemite National Park, Rocky Mountain National Park, the eastern Sierra Nevada, Cochise Stronghold, Hueco Tanks State Park, and Mount Lemmon with people that shared similar values brought me back to a feeling of connection. Rock climbing became my missing identity puzzle piece; a reincarnation of my first world.

Ni’halgai, the fourth world of my journey: I am Tábaahá, the Edgewater clan, born for Tł’ógí, the Zia clan. My maternal grandfather is Táchii’nii and paternal grandfather is Tódích’íi’nii. After 16 years of redpoints, boulders, summits, alpine ascents, and first ascents, I am an Indigenous rock climbing guide, guide company owner, professional rock climbing athlete, and advocate for the protection of sacred land resources. My fourth world came about after I resolved that I am committed to the path I am on and that I do not want my story to be unique. It is my goal to provide the same access that was gifted to me to Indigenous youth as a means of connection to their land and to their heritage.

The author, Aaron Mike, bouldering in Northern Arizona (Hopi, Yavapai, Western Apache, Ancestral Puebloan lands). PC: James Q Martin

Simply acknowledging Indigenous heritage and history as a part of the land is not the only answer. It is a step in our First World, eventually leading to our Fourth World of evolution. Accountability is not only assumed with the people and organizations in the industry that are trying to make a sustainable difference, but should be carried out through the actions of each and every climber. Throughout the decades and in my personal experience there has been a culture in climbing that tries to nullify existing law on sacred lands, specifically on the Navajo Nation. Climbers drill fresh bolts and pay to poach sacred formations behind excuses like “good intentions” or “having a Native friend.” These illegal actions are a modern day conquer-and-destroy mentality that fails to respect Indigenous sovereignty and deteriorates the credibility of potential sustainable rock climbing efforts.

Indigenous Peoples are not extinct. Not everything needs to be climbed. Recreation must take a back seat to respecting Indigenous practices that have existed for millennia. Media channels promote first ascents, first free ascents, first descents, and sending of beautiful lines in remote places on rock, snow, or water, which can overlook Indigenous values. The actions that we take must respect Indigenous culture and it is up to us as the greater climbing community to decide the direction that we wish to pursue. Like climbers’ push for Leave No Trace implementation and education, it is up to all of us to push our Local Climbing Organizations to provide information on how to recreate with respect on or near sacred lands and to develop relationships with local Tribes. We must shift the ethos from a western “take” culture in order to not only respect the original stewards of the land, but to ensure that Nahasdzáán, the Earth, will be healthy for our future generations.

Aaron Mike is a Navajo rock climbing guide, a NativeOutdoors athlete, and a Native Lands Regional Coordinator for the Access Fund. Since the time of this being originally published, he has also joined the Protect Our Winters athlete team. Find him here.