Powered by the AAC’s Catalyst grant, Jessica Anaruk and Micah Tedeschi took on to the big walls of the Mendenhall Towers, seven granite towers that rise high above the surrounding Mendenhall Glacier in southeast Alaska.

Found in Translation

Your Guide to Climbing at The New River Gorge

Life: An Objective Hazard

Zach Clanton’s Climbing Grief Fund Story

by Hannah Provost

Photos by AAC member Zach Clanton

Originally published in Guidebook XIII

I.

Zach Clanton was the photographer, so he was the last one to drop into the couloir. Sitting on the cornice as he strapped his board on, his camera tucked away now, his partners far below him and safe out of the avalanche track, he took a moment and looked at the skyline. He soaked in the jagged peaks, the snow and rock, the blue of the sky. And he said hello to his dead friends.

In the thin mountain air, as he was about to revel in the breathlessness of fast turns and the thrill of skating on a knife’s edge of danger, they were close by—the ones he’d lost to avalanches. Dave and Alecs. Liz and Brook. The people he had turned to for girlfriend advice, for sharing climbing and splitboarding joy. The people who had witnessed his successes and failures. Too many to name. Lost to the great allure, yet ever-present danger, of the big mountains.

Zach had always been the more conservative one in his friend group and among his big mountain splitboard partners. Still, year after year, he played the tricky game of pushing his snowboarding to epic places.

Zach is part of a disappearing breed of true dirtbags. Since 2012, he has lived inside for a total of ten months, otherwise based out of his Honda Element and later a truck camper, migrating from Alaska to Mexico as the seasons dictated. When he turned 30, something snapped. Maybe he lost his patience with the weather-waiting in Alaska. Maybe he just got burnt out on snowboarding after spending his entire life dedicated to the craft. Maybe he was fried from the danger of navigating avalanche terrain so often. Regardless, he decided to take a step back from splitboarding and fully dedicate his time to climbing, something that felt more controllable, less volatile. With rock climbing, he believed he would be able to get overhead snow and ice hazards out of his life. He was done playing that game.

Even as Zach disentangled his life and career from risky descents, avalanches still haunted him. Things hit a boiling point in 2021, when Zach lost four friends in one season, two of whom were like brothers. As can be the case with severe trauma, the stress of his grief showed up in his body—manifesting as alopecia barbae. He knew grief counseling could help, but it all felt too removed from his life. Who would understand his dirtbag lifestyle? Who would understand how he was compelled to live out of his car, and disappear into the wilderness whenever possible?

He grappled with his grief for years, unsure how to move forward. When, by chance, he listened to the Enormocast episode featuring Lincoln Stoller, a grief therapist who’s part of the AAC’s Climbing Grief Fund network and an adventurer in his own right—someone who had climbed with Fred Beckey and Galen Rowell, some of Zach’s climbing idols—a door seemed to crack open, a door leading toward resiliency, and letting go. He applied to the Climbing Grief Grant, and in 2024 he was able to start seeing Lincoln for grief counseling. He would start to see all of his close calls, memories, and losses in a new light.

Photo by AAC member Zach Clanton

II.

With his big mountain snowboarding days behind him, Zach turned to developing new routes for creativity and the indescribable pleasure of moving across rock that no one had climbed before. With a blank canvas, he felt like he was significantly mitigating and controlling any danger. There was limited objective hazard on the 1,500-foot limestone wall of La Gloria, a gorgeous pillar west of El Salto, Mexico, where he had created a multi-pitch classic called Rezando with his friend Dave in early 2020. Dave and Zach had become brothers in the process of creating Rezando, having both been snowboarders who were taking the winter off to rock climb. On La Gloria, it felt like the biggest trouble you could get into was fighting off the coatimundi, the dexterous ringtail racoon-like creatures that would steal their gear and snacks.

After free climbing all but two pitches of Rezando in February of 2020, when high winds and frigid temperatures drove them off the mountain, Zach was obsessed with the idea of going back and doing the first free ascent. He had more to give, and he wasn’t going to loosen his vise grip on that mountain. Besides, there was much more potential for future lines.

Dave Henkel on the bivy ledge atop pitch eight during the first ascent of Rezando. PC: Zach Clanton

But Dave decided to stay in Whistler that next winter, and died in an avalanche as Zach was in the process of bolting what would become the route Guerreras. After hearing the news, Zach alternated between being paralyzed by grief and manically bolting the route alone.

In a world where his friends seemed to be dropping like flies around him, at least he could control this.

Until the fire.

It was the end of the season, and his friend Tony had come to La Gloria to give seven-hour belays while Zach finished bolting the pitches of Guerreras ground-up. Just as they touched down after three bivvies and a successful summit, Tony spotted a wildfire roaring in their direction. Zach, his mind untrained on how fast forest fires can move, was inclined to shrug it off as less of an emergency than it really was. Wildfire wasn’t on the list of dangers he’d considered. But the fire was moving fast, ripping toward them, and it was the look on Tony’s face that convinced Zach to run for it.

In retrospect, Zach would likely not have made it off that mountain if it weren’t for Tony. He estimates they had 20 minutes to spare, and would have died of smoke inhalation if they had stayed any longer. When they returned the next winter, thousands of dollars of abandoned gear had disintegrated. The fire had singed Zach’s hopes of redemption—of honoring Dave with this route and busying his mind with a first ascent—to ash. It would only be years later, and through a lot of internal work, that Zach would learn that his vise grip on La Gloria was holding him back. He would open up the first ascent opportunity to others, and start to think of it as a gift only he could give, rather than a loss.

But in the moment, in 2021, this disaster was a crushing defeat among many. With the wildfire, the randomness of death and life started to settle in for Zach. There was only so much he could control. Life itself felt like an objective hazard.

III.

In January 2022, amid getting the burnt trash off the mountain and continuing his free attempts on Guerreras, Zach took a job as part of the film crew for the National Geographic show First Alaskans—a distraction from the depths of his grief. Already obsessed with all things Alaskan, he found that there was something unique and special about documenting Indigenous people in Alaska as they passed on traditional knowledge to the next generation. But on a shoot in Allakaket, a village in the southern Brooks Range, his plan for distraction disintegrated.

In the Athabascan tradition, trapping your first wolverine as a teenager is a rite of passage. Zach and the camera crew followed an Indigenous man and his two sons who had trapped a wolverine and were preparing to kill and process the animal. In all of his time spent splitboarding and climbing in these massive glaciated mountains that he loved so much, Zach had seen his fair share of wolverines— often the only wildlife to be found in these barren, icy landscapes. As he peered through the camera lens, he was reminded of the time he had wound through the Ruth Gorge, following wolverine tracks to avoid crevasses, or that time on a mountain pass, suddenly being charged by a wolverine galloping toward him. His own special relationship with these awkward, big-pawed creatures flooded into his mind. What am I doing here, documenting this? Was it even right to allow such beautiful, free creatures to be hunted in this way? he wondered.

The wolverine was stuck in a trap, clinging to a little tree. Every branch that the wolverine could reach she had gnawed away, and there were bite marks on the limbs of the wolverine where she’d attempted to chew her own arm off. Now, that chaos and desperation were in the past. The wolverine was just sitting, calm as can be, looking into the eyes of the humans around her. It felt like the wolverine was peering into Zach’s soul. He could sense that the wolverine knew she would die soon, that she had come to accept it. It was something about the hollowness of her stare.

He couldn’t help but think that the wolverine was just like all his friends who had died in the mountains, that there had to have been a moment when they realized they were going to be dead—a moment of pure loneliness in which they stared death in the face. It was the loneliest and most devastating way to go, and as the wolverine clung to the tree with its battered, huge, human-like paws, he saw the faces of his friends.

When would be the unmarked day on the calendar for me? He was overwhelmed by the question. What came next was a turning point.

With reverence and ceremony, the father led his sons through skinning the wolverine, and then the process of giving the wolverine back to the wild. They built a pyre, cutting the joints of the animal, and burning it, letting the smoke take the animal’s spirit back to where it came from, where the wolverine would tell the other animals that she had been treated right in her death. This would lead to a moose showing itself next week, the father told his sons, and other future food and resources for the tribe.

As Zach watched the smoke meander into the sky through the camera lens, the cycle of loss and life started to feel like it made a little more sense.

IV.

After a few sessions with Lincoln Stoller in the summer of 2024, funded by the Climbing Grief Fund Grant, Zach Clanton wasn’t just invested in processing and healing his grief—he was invested in the idea of building his own resiliency, of letting go in order to move forward.

On his next big expedition, he found that he had an extra tool in his toolbox that made all the difference.

They had found their objective by combing through information about old Fred Beckey ascents. A bush plane reconnaissance mission into the least mapped areas of southeast Alaska confirmed that this peak, near what they would call Rodeo Glacier, had epic potential. Over the years, with changing temperatures and conditions, what was once gnarly icefalls had turned into a clean granite face taller than El Cap, with a pyramid peak the size of La Gloria on top. A couple of years back, they had received an AAC Cutting Edge Grant to pursue this objective, but a last-minute injury had foiled their plans. This unnamed peak continued to lurk in the back of Zach’s mind, and he was finally ready to put some work in.

As Zach and James started off up this ocean of granite, everything was moving 100 miles per hour. Sleep deprived and totally strung out, they dashed through pitch after pitch, but soon, higher on the mountain, Zach started feeling a crushing weight in his chest, a welling of rage that was taking over his body and making it impossible to climb. He was following James to the next belay, and scaring the shit out of himself, unable to calm his body enough to pull over a lip. This was well within his abilities. What was happening? How come he couldn’t trust his body when he needed it most?

At the belay, Zach broke down. He was suddenly feeling terrified and helpless in this ocean of granite, with the unknown hovering above him. They had stood on the shore, determined to go as far into the unknown sea of rock as they could, while still coming back. When would be the breaking point? Could they trust themselves not to go too far?

Hesitantly at first, Zach spoke his thoughts, but he quickly found that James, who had similar experiences of losing friends in the mountains, understood what he was going through. As they talked through their exhaustion and fear and uncertainty, they recognized in each other the humbling experience of being uprooted by grief, and also the ability to process and keep going. They made the decision to keep climbing until sunset, swapping leads as needed. Zach was inspired, knowing how shattered he had felt, and yet still able to reach deep within to push through. With the resiliency tools he had worked on with Lincoln, this experience didn’t feel so debilitating.

Yet resilience also requires knowing when to say no, when something is too much. After a long, uncomfortable bivy halfway up a 5,000-foot rock climb, the two decided to start the long day of rappels, wary of a closing weather window.

Zach Clanton and his dog, Gustaf Peyote Clanton, at Widebird. “He [Gustaf] is a distinguished gentleman.” Photo by Holly Buehler

Back safely on the glacier, the two climbing partners realized it was their friend Reese’s death day. Taking a whiskey shot, and pouring one out for Reese, they parted ways—James to his tent for a nap, and Zach to roam the glacier.

The experience of oneness he found, roaming that desolate landscape, he compares to a powerful psychedelic experience. It was a snowball of grief, trauma, resilience, meditation, the connection he felt with the friends still here and those gone. It was like standing atop the mountain before he dropped into the spine, and the veil between this world and those who were gone was a little less opaque. He felt a little piece of himself—one that wanted a sense of certainty—loosen a little. The only way he was going to move forward was to let go.

He wasn’t fixed. Death wouldn’t disappear. Those friends were gone, and the rift they left behind would still be there. But he was ready to charge into the mountains again, and find the best they had to offer.

Support This Work—Climbing Grief Fund

The Climbing Grief Fund (CGF) connects individuals to effective mental health professionals and resources and evolves the conversation around grief and trauma in the climbing, alpinism, and ski mountaineering community. CGF acts as a resource hub to equip the mental health of our climbing community.

Sign Up for AAC Emails

The Height of Mountains

Navajo Rising: An Indigenous Emergence Story

Shiprock (Tsé Bit a í, “winged rock”) rises over 1,500 feet above the desert floor of the Navajo Nation in San Juan County, New Mexico (Diné, Pueblos, Ute lands). Shiprock was a sought-after summit during the late 1930s, until the first ascent was done in 1939 by David Brower and Sierra Club team. It marks one of the first times bolts were placed for protection in the history of North American climbing. However, the rock formation is highly sacred to the Navajo people, having historical and religious significance. In 1966, the Navajo Nation banned all climbing on their lands, including Shiprock.

by Aaron Mike

This Indigenous People’s Day, we’re reposting a beautifully written essay by Navajo climber Aaron Mike that we published in 2019.

Acknowledging the roots and conceptualizations of the outdoor activities that we so passionately pursue enriches our participation and ties us to the land, as well as to one another. When we view our industry through a historical lens, we inevitably hear about John Muir, Sir Edmund Hillary, Royal Robbins, and other giants of outdoor recreation. We revere them based on their successes and physical accomplishments. There is one similarity between them that is rarely mentioned: the entirety of their recreational pursuits took place on ancestral homelands of Indigenous Peoples. The Miwok and Piute resided amongst the majestic granite walls of what is now Yosemite National Park. The Havasupai and Hualapai cultivated the areas of the Grand Canyon. The Shoshone, Bannock, Blackfoot, Crow, Flathead, Gros Ventre, and the Nez Perce tribes inhabited what is now Grand Teton National Park. The history and heritage of Indigenous peoples as an inherent part of the lands on which we recreate is a topic that must be part of the conversation if we are to achieve a responsible, sustainable, and inclusive industry. Especially today, this topic is paramount not only because it enhances the care and stewardship of the lands we all love, but also because it is a statement against the systematic dehumanization of a people.

Diné Bahane’, the Navajo creation story, tells of the journey through three worlds to the fourth world, where the Navajo people now reside. The story details chaos and drama as the Diné, or “Holy people,” moved through Black World, which contained no light; Blue World, which contained light; and Yellow World, which contained great rivers. Eventually, in the 4th world, White World, the Diné would assume human form after gaining greater intelligence and awareness. Through these worlds deities, vegetation, and animals accompanied the Diné, as well as our four sacred mountains; Sis Naajini (Blanca Peak), Tsoodził (Mount Taylor), Dook’o’oosłid (the San Francisco Peaks) and Dibé Nitsaa (Mount Hesperus).

Like the story of my people, my tribe, I have gone through many different worlds to walk the path that I am on today. My first world, Ni’hodiłhił, consisted of a surreal state of constantly spending time in the outdoors on the Navajo Nation from Sanders, AZ to Monument Valley, AZ, as well as my hometown of Gallup, NM. Weekends and summers were spent playing with my cousins through the tranquility provided, or turbulence imposed, by our Mother Nature. My grandparents taught me about sheep herding with blue heelers, building hogáns, and butchering sheep. I learned how to take care of horses and cattle, and how to live off of the land. During the spring and summer I spent nights sleeping under the stars and a Pendleton blanket in the back of my grandfather’s early 1990’s Ford F-150. During the fall and winter, I woke up sweating under a sheep woolskin blanket next to a wood burning stove that my grandfather had installed.

I blinked my eyes and I was in the second world of my journey, Ni’hodootł’izh, far from the Navajo Nation in the Northwest, transported to an environment where all of those activities that had made me feel so real were not customary or necessary, and were even frowned upon. Due to my Diné heritage and my personality, being in the outdoors is a necessity. It is hardwired into my entire being. In this second world, the connection to the land that I had experienced and loved was diverted and diminished. I began to feel disconnected from my Diné roots and felt a growing spiritual void.

I awoke for my first day in a new desert environment and into my third world, Ni’haltsoh. By this time, high school, my identity was in constant flux. I struggled to find my place and individual path in a sea of foreign values and ambitions. I blew through various sports, political ideas, social scenes, and academic areas of study. Amidst the chaos of these years, I found a vehicle that would take me into my fourth world, rock climbing. Being on the walls and boulders in Yosemite National Park, Rocky Mountain National Park, the eastern Sierra Nevada, Cochise Stronghold, Hueco Tanks State Park, and Mount Lemmon with people that shared similar values brought me back to a feeling of connection. Rock climbing became my missing identity puzzle piece; a reincarnation of my first world.

Ni’halgai, the fourth world of my journey: I am Tábaahá, the Edgewater clan, born for Tł’ógí, the Zia clan. My maternal grandfather is Táchii’nii and paternal grandfather is Tódích’íi’nii. After 16 years of redpoints, boulders, summits, alpine ascents, and first ascents, I am an Indigenous rock climbing guide, guide company owner, professional rock climbing athlete, and advocate for the protection of sacred land resources. My fourth world came about after I resolved that I am committed to the path I am on and that I do not want my story to be unique. It is my goal to provide the same access that was gifted to me to Indigenous youth as a means of connection to their land and to their heritage.

The author, Aaron Mike, bouldering in Northern Arizona (Hopi, Yavapai, Western Apache, Ancestral Puebloan lands). PC: James Q Martin

Simply acknowledging Indigenous heritage and history as a part of the land is not the only answer. It is a step in our First World, eventually leading to our Fourth World of evolution. Accountability is not only assumed with the people and organizations in the industry that are trying to make a sustainable difference, but should be carried out through the actions of each and every climber. Throughout the decades and in my personal experience there has been a culture in climbing that tries to nullify existing law on sacred lands, specifically on the Navajo Nation. Climbers drill fresh bolts and pay to poach sacred formations behind excuses like “good intentions” or “having a Native friend.” These illegal actions are a modern day conquer-and-destroy mentality that fails to respect Indigenous sovereignty and deteriorates the credibility of potential sustainable rock climbing efforts.

Indigenous Peoples are not extinct. Not everything needs to be climbed. Recreation must take a back seat to respecting Indigenous practices that have existed for millennia. Media channels promote first ascents, first free ascents, first descents, and sending of beautiful lines in remote places on rock, snow, or water, which can overlook Indigenous values. The actions that we take must respect Indigenous culture and it is up to us as the greater climbing community to decide the direction that we wish to pursue. Like climbers’ push for Leave No Trace implementation and education, it is up to all of us to push our Local Climbing Organizations to provide information on how to recreate with respect on or near sacred lands and to develop relationships with local Tribes. We must shift the ethos from a western “take” culture in order to not only respect the original stewards of the land, but to ensure that Nahasdzáán, the Earth, will be healthy for our future generations.

Aaron Mike is a Navajo rock climbing guide, a NativeOutdoors athlete, and a Native Lands Regional Coordinator for the Access Fund. Since the time of this being originally published, he has also joined the Protect Our Winters athlete team. Find him here.

Guidebook X

The AAC’s Guidebook is our annual storytelling publication, capturing the stories of the people and issues that are at the forefront of the climbing communities mind. AAC members receive a print copy annually.

In this issue, we feature the filmography of up-and-coming director Marie-Louise Nkashama, explore the prolific history of route developer Jeff Jackson, investigate how groups on the ground are making climbing more inclusive, and highlight the story of an AAC volunteer who has given so much back to the community through YOSAR and storytelling.

Our feature articles do a deep dive into the AAC’s work to protect Pine Mountain, CA, from deforestation; retell the story of cutting-edge expeditions to Proboscis; highlight the intricacies of the conversation around oppressive and offensive route naming; and reminisce about the first successful climbing expedition to the Antarctic.

From cutting-edge climbing stories, to public lands, inclusive climbing community, and just plain cool climbers, you can find the breadth of the climbing community in these pages.

Rewind the Climb: Pete Schoening’s Miracle Belay on K2

by Grey Satterfield

artwork by James Adams

photos from the Dee Molenaar Collection

It happens every day, in every climbing gym across the country: the belay check. It can swell up a wave of anxiety for new climbers or a wave of frustration for more experienced ones, but no matter where you are in your climbing journey, you’ve done it. Everyone has demonstrated their ability to stop a falling climber. But what about stopping two climbers? What about stopping five? And what about stopping five without the convenience of a Gri-Gri, in a raging storm at 8,000 meters, hanging off the side of the second highest mountain in the world?

Pete Schoening checks all those boxes, and his miracle belay during an early attempt of K2 is one of the most famous in all of climbing history. It’s an awesome reminder that in climbing, much like in life, a lot of things change, but a lot of things don’t.

In 1953, during the third American expedition to K2, eight climbers funded by the American Alpine Club built their high camp at nearly 7,700m. The team consisted of Pete Schoening, Charles Houston, Robert Bates, George Bell, Robert Craig, Art Gilkey, Dee Molenaar, and Tony Streather.

On the seventh day of the ascent, climbing without oxygen, Schoening and his partners were within reach of the summit. With the first ascent of the long-sought peak tantalizingly close, the weather turned, trapping the climbers for10 days at nearly 8,000m. The storm raged on, destroying tents and dwindling supplies. Then Gilkey developed thrombophlebitis—a life-threatening condition of blood clots brought on by high altitude. If these clots made it into his lungs, he’d die. The team had no choice but to descend. Without hesitation, they abandoned the summit attempt and put themselves to work getting Gilkey to safety. With an 80mph blizzard compounding their effort, the climbing team bundled their injured comrade in a sleeping bag and a tent and, belayed by Schoening, began to lower him down the perilous walls of rock and ice.

After an exhausting day of descending, they had made it only 300m but were in sight of Camp VII, which was perched on a ledge another 180m further across the icy slope. Craig was the first to reach the site and began building camp. Then the real disaster struck.

As Bell was working his way across the steep face, he slipped and began to rocket down the side of the mountain. Bell was tied to Streather, who was also pulled off his feet and down the slope. The rope between the two climbers then became entangled with those connecting the team of Bates, Houston, and Molenaar, pulling them off in turn. The five climbers, along with the tethered Gilkey, began careening down the near vertical face, rag-dolling down the mountain over 100m and speeding towards the edge: a 2,000m fall to the glacier below.

At the last second—as the weight of six climbers slammed into him— Schoening thrust his ice axe into the snow behind a boulder and, with a hip belay, brought the climbers to a stop. The nylon rope (a relatively new piece of climbing gear at the time) went taught and shrank to half its diameter, but it did not snap. The hickory axe held the strain. Schoening, rope wrapped tightly around his shoulders, had performed what is considered one of the greatest saves in mountaineering history—known now and forever known as “The Belay.”

“When you get into something like mountain climbing,” Schoening said afterwards, “I’m sure you do things automatically. It’s a mechanical func- tion. You do it when necessary without giving it a thought of how or why.”

However, the incident was not without tragedy. As the team recovered from the fall and established a forced bivy, they discovered that Gilkey, bundled in sleeping bag and tent, had vanished. There is speculation that he cut himself free in order to save the lives of his friends above.

Schoening, always humble about the feat, was later awarded the David A. Sowles Memorial Award for his heroics by the American Alpine Club in 1981 as a “mountaineer who has distinguished himself, with unselfish devotion at personal risk or sacrifice of a major objective, in going to the assistance of fellow climbers imperiled in the mountains.”

Fifty-three years later, in 2006, 28 descendants of the surviving team gathered, calling themselves “The Children of ‘The Belay.’” All owed their lives to Schoening—and his ice axe—high on K2. The axe, which some have called the holy grail of mountaineering artifacts, is on permanent display at the American Mountaineering Museum in Golden, Colorado.

Much has changed in the world of climbing over the past 70 years. When Schoening headed up K2 in 1953, assisted-braking belay devices were yet to be invented. The AAC provided no rescue services as a benefit of membership. Nobody owned an InReach or a satellite phone. To survive in the mountains in that era was to rely solely on your team—on the trust that comes with tying in together and the knowledge that a friend is watching your back.

So we would do well to remember Pete Schoening and his belay—to hold the other end of the rope is a serious affair. The next time you go out climbing, don’t forget to give your belayer a high-five and a hug.

Grey Satterfield is the digital marketing manager for the AAC. He has a decade of experience managing climbing gyms and loves to share his passion for climbing with anyone who will listen, be it through writing, photography, or swapping stories around the campfire.

In Search of Yosemite's Heart: One Writer's Journey Into the Valley of Giants

by Lauren DeLaunay Miller

photos by the Ellie Hawkins and Molly Higgins collections

Ellie Hawkins during an early ascent of the North America Wall, 1973, Yosemite National Park, CA. Land of the Central Sierra Miwok people. Keith Nannery.

To steal from author John Green, I fell in love with rock climbing the way you fall asleep: slowly, and then all at once. I was an indoorsy undergraduate at the University of North Carolina when I fell face-first into the world of climbing, thanks in large part to a picture in a magazine. My love for climbing has always been attached to an obsession with Yosemite, that ultimate proving ground of American rock climbers, but before I could make my way out there myself, I tried as hard as I could to connect with that world while still confined to the walls of libraries in Chapel Hill. Climbing literature was my portal, but it didn’t take long to exhaust my options. I don’t know if I could have articulated to you then why—or even that I was—searching for books written by women, but what I did know was that I was going to learn as much as I could about my heroes and try as best as I could to follow in their footsteps.

Five years after graduating, I moved into my new home in the back of Camp 4. The Yosemite Search & Rescue site has a mystical, magical air. To walk into the site is to, quite literally, walk in the footsteps of giants. I’ve climbed at a lot of American climbing destinations, from the New and Red River Gorges in the East, to Indian Creek, Joshua Tree, Red Rock Canyon, and Rocky Mountain National Park, but nowhere have I found the lore as strong as in Yosemite.

At my now-local crag, we often refer to routes as “that 10b arete” or “the 5.11 crack to the left of the 12a.” But in Yosemite, routes have names. Astroman, the Central Pillar of Frenzy, Steck-Salathé, The Nose! We know their first ascensionists, and we know their stories. And these stories get passed down, sometimes in writing but often at campfires and dinner parties, fueled by whiskey or coffee or both. So while it didn’t take long for me to realize that there was a gap between the women’s stories I was hearing and those I was reading, it did take me a few years to muster up the courage to try to close that gap myself.

The idea for the book lived quietly in my head, but as it became louder and louder, I started to shyly share it with my climbing partners. “Don’t you think it would be cool,” I’d mutter, “if there were a whole book about women climbing in Yosemite?” The more I shared my vision, the more it grew. I started scanning old climbing magazines, making lists of the women I’d need to include. Friends started sending me articles they came across, screenshots of Supertopo forums and Mountain Project threads. I spent days at the new Yosemite Climbing Association museum in Mariposa going through thousands of pages of old magazines. At first, everything was centered on building “the list,” my dream list of contributors, and eventually I thought it might just be enough to submit as a book proposal.

Ellie Hawkins gets prepped for the void on the first ascent of Dyslexia (VI 5.10d A4), completed solo, 1985. Bruce Hawkins

I’ve always been the type of person who gets stuck on an idea and can’t shake it until I’ve seen it through. When I started climbing, I gave myself five years to climb El Cap, even though at the time I barely knew how to belay. Nearly every decision I made from that moment propelled me toward my goal, and I recognized the same level of obsession once I became hooked on the idea for this book. I made my proposal and sent it off to three publishing companies. I was living in a tent cabin in Camp 4 by then, and while my own world was consumed by Yosemite, I didn’t know if my idea would resonate outside of my community. But my first conversation with Emily White at Mountaineers Books soothed my concerns, and I knew my project would be safe under her supervision. I signed on the dotted line; I had just over a year to make this thing happen.

I started with the people I knew or could get personal introductions to. I met with Babsi Zangerl in her campervan in the Valley, and she was eager to be a part of the book. That was the moment I thought that I might actually be able to pull this off. Soon, Liz Robbins called, thanks to some coaxing by Ken Yager at the Yosemite Climbing Association. I drew on all the connections I’d made through my climbing career, and every response gave me a jolt of electricity. Fourteen months later, I turned in everything I had: 38 stories, totaling over 76,000 words.

Molly Higgins leading to The Nose’s famous feature, the Great Roof. AAC member Barb Eastman

When Molly Higgins mentioned to Lauren that she had some old boxes of slides from her time in Yosemite, Lauren knew she had to see them. Prepared to see some faded, blurry images at best, she unearthed dozens of boxes—slide after slide of perfectly preserved photographs documenting some of the most courageous ascents of a generation, including images from the first all-female ascent of The Nose on El Cap in 1977. With the tremendous help of the AAC Library, Lauren organized Molly’s collection into an online exhibit which can be viewed at here.

Ellie Hawkins—the other photo contributer for this piece—might not be a household name in the world of Yosemite climbing, but she certainly should be. She’s the only woman to ever establish a Yosemite big wall first ascent completely solo, with Dyslexia (VI 5.10d A4) in the Ribbon Falls Amphitheater. The route was aptly named. Ellie battled a terrible case of dyslexia that often complicated her climbing. Despite these challenges, an early ascent of El Cap’s North America Wall (5.8 C3) and a solo of Never Never Land (5.10a) earned Ellie’s place among the Valley’s legends. Lauren was able to digitize and preserve Ellie’s collection of slides and prints as well, a few of which are featured here.

One of the greatest gifts of working on this book came in the form of a few phone conversations with Liz Robbins. Liz is the author of one of my favorite pieces in the book, a story written years ago for Alpinist magazine that tells of her experience establishing the first ascent of The Nutcracker Suite (5.8), the first route in Yosemite to be climbed entirely on clean protection. The Nutcracker, as it is commonly known today, was the first route I ever climbed in Yosemite, years before I ended up working on the Search & Rescue team. Having driven all through the night from the mountain West, across the wide open sagebrush of Nevada, up through the winding granite slabs of Tuolumne, and down, at long last, to Yosemite Valley, I woke up at dawn, claimed my spot in Camp 4, and went straight to the Manure Pile Buttress. I once read that a “classic” climb must be at least one, if not all, of these three things: aesthetically pleasing, historically significant, and full of spectacular climbing. The Nutcracker Suite has it all, and it made for an unforgettable first Yosemite experience.

Ellie Hawkins on a solo ascent of Never Never Land (5.10a), Yosemite Valley National Park, CA. Land of the Central Sierra Miwok people. Bruce Hawkins

It’s been more than five years since that first Valley climb, and when I told Liz about my experience climbing it, we realized that because of her and Royal’s decision not to place pitons, the route climbs just about the same way today as it did during her first ascent. Of course, it is greasy with chalk and rubber from thousands of ascents, but it is not scarred the way other Yosemite routes are. Where I smeared, Liz had smeared, and where I stuffed my fingers in the crack, so had she.

Barb Eastman walking out the infamous Thank God Ledge during the first all-female ascent of Half Dome’s Regular Northwest Face(5.9C1),1976. AAC member Molly Higgins

At the end of the story, Liz expresses the mental tug-of-war she often engaged in when climbing. Her doubts about her abilities echoed my own insecurities about the making of this book. Who was I to engage in such an important project? But, as did Liz, I found time and time again that I’d yet to come across the problem that demanded more of me than I could give. Of course, this book is not perfect. There are holes—gaping ones—ones that jump out at me baring teeth and ones that, surely, I will see more clearly with time. But soon we will have in our hands the stories of 38 women who have, at one time or another, found themselves at the center of Yosemite climbing. We start in 1938 and run smack into the present, and it would horrify my editor if she knew that I were still adding stories the day before my first draft was due. But just as Steck & Roper implored us to think of their 50 Classic Climbs as some classic climbs and not the classic climbs, so too do these stories tell of the experiences of some women, not the women. Because there are so many more stories, so many more voices, so many more experiences worth telling and retelling. And as Liz so eloquently writes: I’ve only just begun the excavation.

Lauren DeLaunay Miller served on the Yosemite Search & Rescue team while completing her book, Valley of Giants: Stories from Women at the Heart of Yosemite Climbing (Mountaineers Books, Spring 2022), an anthology of stories that document the history of women’s climbing in Yosemite National Park. Lauren lives in Bishop, CA where she is a founding board member of the Bishop Climbers Coalition and Coordinator for the AAC’s Bishop Highball Craggin’ Classic. She is currently pursuing her master’s degree in Journalism at the University of California in Berkeley.

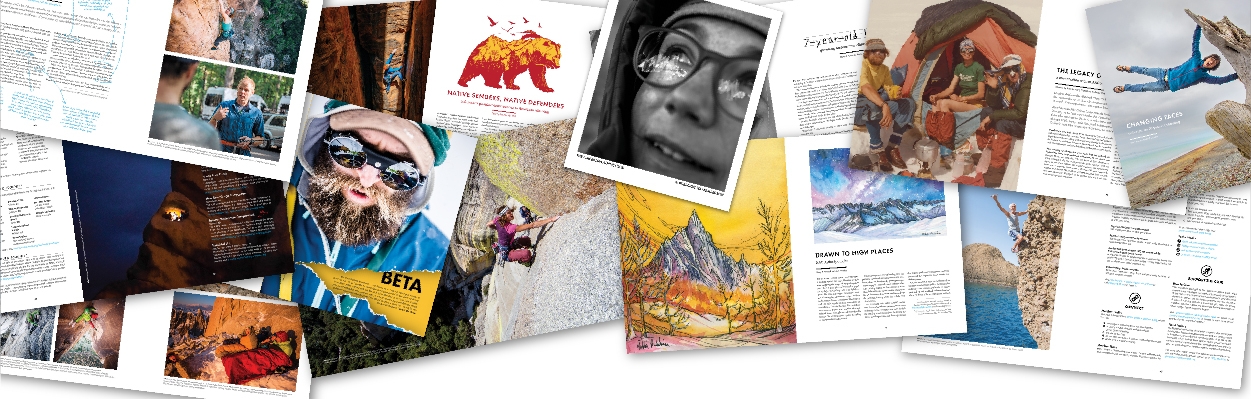

AAC's Guidebook to Membership is Here

Our 2019 Guidebook to Membership is here! The Guidebook serves as a storyboard and yearbook as well as a literal guidebook to Club member benefits. The majority of each issue is dedicated to member photos and stories, working to define (and redefine) the ever-changing faces of American climbing and the Club that serves to unite them. From mountain art to community issues to conservation and advocacy stories, the Guidebook covers many important topics from a unique member-perspective. So, flip on through and get inspired. You might even find a new discount that you didn't even know you had.

Some stories we’re particularly excited about this year include:

Art for the In-Betweens: Artist Spotlight, by Brooklyn Bell

Navajo Rising: An Indigenous Emergence Story, by Aaron Mike

Glacial Views: A Climate Scientist Reflects, by Seth Campbell

1Climb, Infinite Potential: Kevin Jorgeson Breaks Down Walls by Building them

On Pushing: A Grief Story, by Madaleine Sorkin

An Ode to Mobility: the Range of Motion Project Tackles Cotopaxi, by Lauren Panasewicz

…and there’s so much more, including tear-out-and-send policy postcards by Jill Pelto.

The 2018 Guidebook to Membership is Here!

The 2018 Guidebook to Membership is here! The Guidebook is our Club’s collective yearbook. This year’s issue, “the changing faces of the AAC”, features stories and photos by some incredible changemakers in our community as well as information about AAC programs and opportunities. We hope you find it inspiring and informative! If you’ve opted to receive our print publications, you should see it in your mailbox any day now. You can also view the Guidebook online.

Cover photo by Austin Siadak.