Belayer is carried to a helicopter landing zone by Hellgate Cliffs in Utah, using a rope bag as an improvised litter. She had borrowed the leader’s helmet for belaying the pitch, which likely saved her from a much more serious injury. Photo courtesy of Salt Lake County Search and Rescue

The Prescription - August 2021

HEADS UP!

Below are two reports from the upcoming edition of Accidents in North American Climbing that share many similarities. Both involved climber-caused rockfall that hit belayers standing on the ground. Both were at sport climbing areas, where many belayers decide not to wear helmets—though, very fortunately, one of these belayers had borrowed the leader’s helmet because of concern about loose rock. In both cases, the belayer was using an assisted-braking belay device (ABD), and, in one case, this very likely saved the leader from a ground fall and significant injuries. Though rare, these incidents should make climbers think about the value of ABDs—and helmets—for belaying single-pitch climbs.

Belayer Hit by Rockfall

Utah, Wasatch Range, Little Cottonwood Canyon

On August 7, Avery Guest (female, 20) was climbing with her partner for the day, Jake Bowles (21), at Hellgate Cliffs, a limestone area high in Little Cottonwood. It was Avery’s second time climbing/belaying outdoors. Jake is an experienced climber.

They chose Monkey Paw (5.9), a single-pitch sport climb, for their first route of the day. Jake was leading, and he got about four bolts up the route (approximately 50 feet off the ground) when he reached for what looked like a good hold. When he weighted the hold, a torso-size rock detached from the wall. It split into three pieces, and one of them landed on Avery, knocking her unconscious. Jake fell approximately 10 feet, pulling Avery about a foot off the ground. She was using a Grigri, which caught Jake’s fall.

Avery regained consciousness quickly and noticed she had an open fracture on her right arm. She managed to lower her partner with her left hand, and he untied her from the belay system. She had post-traumatic amnesia, repeating questions multiple times. They called 911 at about 10:20 a.m. United Fire Authority paramedics and Salt Lake County Search and Rescue responded to the scene within 30 minutes. They gave her pain medication and improvised a litter with Jake’s rope bag in order to carry her about 100 feet down and away from the base of the rock, where Lifeflight could hoist Avery and transport her to the hospital for treatment.

She had two broken bones in her right arm that needed surgery, plus lacerations on her forehead and leg. She also had bleeding in her brain, but managed to avoid brain surgery. Jake suffered only minor scrapes and bruises during the fall.

ANALYSIS

Avery did not have a helmet, so Jake let her use his, knowing there might be rockfall in the area. If Avery had not been wearing Jake’s helmet, her head injuries could have been much worse and possibly fatal. The belay stance for this route was small and surrounded by steep, rocky slopes. Otherwise, she may have been able to move out of the way of the falling rock. (Source: Avery Guest.)

Rockfall Onto Belayer

Colorado, Rifle Mountain Park, Ruckman Cave

At approximately 4 p.m. on September 26, a climber started up The Promise, a 5.12c sport route on the left side of the Ruckman Cave. Just before a ledge at the start of the steep climbing on the route, the climber pulled onto a chalked-up jug that ripped out of the wall. The broken jug, along with more rocks and debris, rained down on the belayer. The climber’s fall was held at the first bolt of the route, and he slammed into the wall sideways, from which he sustained soreness and bruising. The belayer narrowly avoided being hit in the head or upper body by the debris and took all of the damage to his right leg. Fortunately, a visit to the emergency department confirmed no broken bones. (Source: Climber’s report at MountainProject.com.)

ANALYSIS

This incident highlights a paradox often seen at sport climbing areas: The climbers who choose to wear helmets while sport climbing more often are the ones leading or top-roping the climb, not necessarily the belayers and bystanders below the route. Yet, arguably, the belayer is much more likely to be hit by rockfall, which is fairly common in Rifle Mountain Park. More common than helmets at Rifle’s crags are assisted-braking belay devices, which can be a lifesaver in accidents like this one, when the belayer may be severely distracted or even incapacitated by rockfall. (Source: The Editors.)

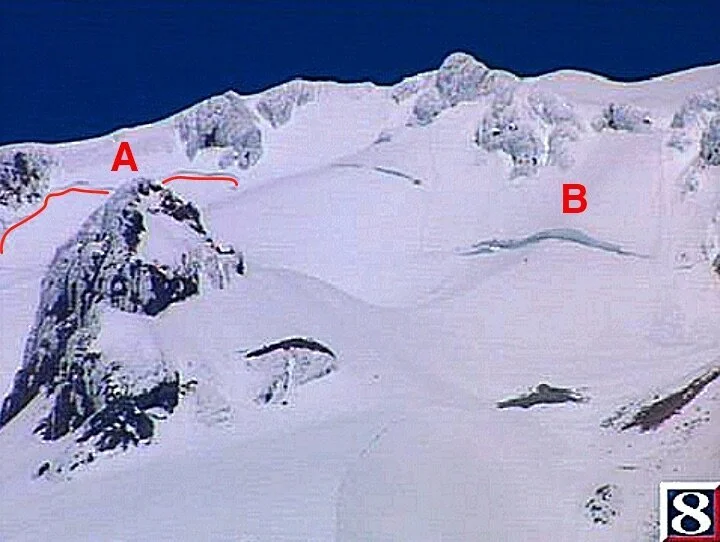

Granite Peak from the south, showing A) Location of climber after fall from the Snowbridge, the saddle directly above; B) site of rappel anchor failure; and C) Position of fallen climber. Photo by Gallatin County Search and Rescue

MONTANA’S DANGEROUS HIGH POINT

In the two most recent editions of ANAC, we’ve published reports about numerous incidents on Granite Peak in Montana. One of the more difficult state high points, Granite Peak has semi-technical and technical climbs on several of its faces and ridges. Summer is peak season for the mountain, and it’s worth reading our reports before heading up there.

Rockfall, Anchor Failure (2021 ANAC): Natural rockfall during an attempt on the Notch Couloir and north ridge destroyed a belay anchor, with nearly disastrous results.

Fall on Snow and Anchor Failure (2021 ANAC): Two falls occurred on September 5 on the east ridge, the standard route up Granite Peak, one of them resulting in a fatality.

Unroped Falls in Class III/IV Terrain (2020 ANAC): Two falls occurred within the same week in August on the Southwest Ramp route of Granite Peak.

Fall on Ice | Inadequate Gear, Failure to Self-Arrest (2020 ANAC): Two climbers became disoriented after summiting by the east ridge, bivouacked below the summit, and then rappelled the north face to the Granite Glacier, for which they were ill-equipped.

DON’T BLAME THE ROCK

In the June Prescription, we posted a short list of tips for optimizing cam placements, originally published in ANAC 2019. Several climbers from Devil’s Lake in Wisconsin took exception to our generalization about cam placements in the Lake’s “clean but slippery” cracks. AAC member Matthew Clausen elaborated in the following letter to the editor, making some great points about the dangers of blaming the rock for cams that don’t hold.

Devil’s Lake, Wisconsin. Photo by Matthew Clausen

Like many climbers, I pay attention to the AAC’s Accidents in North American Climbing. I value the continued learning required to climb safely. While reading June’s “Prescription,” I felt concerned about this warning: "Numerous reports document that well-placed cams can pull out of wet or dirty rock or even perfectly clean but slippery stone like Yosemite granite or Devil’s Lake quartzite."

In more than a decade of climbing at Devil's Lake, I have never seen a cam slip out of a good placement. All reports of this happening, that I am aware of, were better explained by bad placement upon review. Most often, the failed cams were in an outward flaring crack or without the lobes properly engaged.

I agree with the AAC recommendations that climbers continue to learn more about what makes for a good placement, seek qualified instruction and mentoring, and remember to back up crucial placements. The learning process and experience help us tell fact from myth.

Myths about climbing skills are potentially dangerous. If climbers wrongly believe cams are unsafe in the Baraboo Range’s hard, smooth quartzite, they may feel compelled to:

1) Use less efficient gear for protection, or

2) Commit to unnecessary runouts, or

3) Become lax about the subjective hazard of poorly placed cams because they don’t believe a good placement is even possible.

Rather than blaming the geology, we need to combat the complacency of cam placements: These are not magical devices that will hold a fall in any crack. We will bear responsibility for the quality of our decisions.

Sincerely,

Matthew Clausen, Madison, Wisconsin

THE SHARP END VISITS COLORADO

Listen to Episode 67 of the Sharp End Podcast for the story of a helicopter rescue on the long Ellingwood Ridge of La Plata Peak, a Colorado 14er.

WANTED: CLIMBERS WITH INJURED KNEES

Researchers at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School are seeking climbers to participate in a research survey looking at climbing-related knee injuries. You are eligible to participate in this study if you are 18 to 89 years old, climb at least four times per year, and have sustained a knee injury in a climbing-related incident. The anonymous online survey asks injured people about how much they climb and where they climb, how the knee injury happened, and how they recovered. The survey takes about 10 minutes to complete.

The monthly Accidents Bulletin is supported by adidas Outdoor and the members of the American Alpine Club.