The Prescription - May 2021

A huge avalanche in July stripped the north face of Mt. Belanger in Jasper National Park, Canada, down to bare glacial ice. Photo by Grant Statham

The Prescription - May 2021

KNOW THE ROPES: SUMMER AVALANCHES

Spring and Summer Hazards for Mountaineers

It’s springtime and that means snow slopes have stabilized and avalanche danger is a thing of the past, right? Not so fast. For mountaineers and skiers, avalanche season continues well into summer. And in the warmer months, mountaineers account for the large majority of fatal avalanche incidents.

For the 2020 edition of Accidents in North American Climbing, Seattle-based ski mountaineering guide and avalanche forecaster Matt Schonwald wrote an in-depth “Know the Ropes” article about mountaineering avalanches. At the top of his article, Matt described the problems with these avalanches and the reasons many climbers are less than fully prepared:

Spring avalanche on the Ptarmigan Glacier in Rocky Mountain National Park. Note the track on the left. A party of climbers/skiers climbed this slope about one hour before the slide. Photo by Dougald MacDonald

“Although a large majority of avalanche fatalities occur in the winter months, avalanches are not uncommon in the long days of late spring and early summer. According to the national database compiled by the Colorado Avalanche Information Center (CAIC), since 1951 in the United States, 39 out of 44 avalanche fatalities in June and 31 out of 43 in May have involved climbers.

“Most backcountry skiers and winter mountaineers in avalanche-prone areas have some knowledge of the hazards and carry basic avalanche safety equipment, such as transceivers, probes, and shovels…. But preparation for avalanche hazards in the spring and summer mountaineering season is not as widespread or systematic. Most avalanche training is skewed toward winter travelers, and many avalanches that affect mountaineers occur in terrain not covered by avalanche forecasts or after avalanche centers have shut down for the season.

“At the same time, the consequences of an avalanche are at least as great for mountaineers in spring and summer as they are during the winter months. As the winter snowpack melts back, additional hazards are exposed. Cliffs, narrow couloirs, exposed crevasses or boulder fields, and other terrain traps make an encounter with even a small avalanche potentially fatal.

“Mountains big and small possess the potential to bury or injure you with the right combination of unstable snow, terrain, and a trigger—often someone in your party. It’s not only important to recognize these hazards but also to have the discipline to respect the problem and choose another route or wait till the risk decreases. In preparing to enter avalanche terrain, the mountaineer must be focused more on avoiding avalanches than on surviving one, and that is the focus of this article.”

Matt’s story goes on to describe how to recognize avalanche hazards in mountaineering settings and how to plan climbs to minimize the hazards. If you’re contemplating a climbing or skiing trip in snowy mountains this season, this article is essential reading. If you prefer a PDF copy, log in to your profile at the AAC website and look under Publications in the member benefits area—you can download the complete 2020 ANAC there.

FROM THE ARCHIVE: A Real-World Example From Mt. Hood

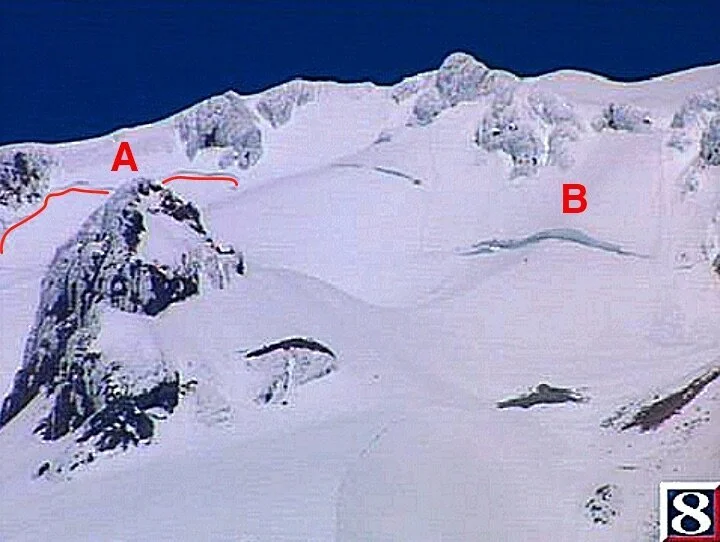

Mt. Hood’s south side, about 24 hours after the avalanche on May 31, 1998. (A) The 300-foot crown fracture extended across the whole slope above Crater Rock, varying from one to five feet high. (B) The Hogsback bergschrund, below the Pearly Gates. Screen shot from KGW-Television cam at Timberline Lodge

In the 1999 edition of ANAC, we described a tragic incident on Mt. Hood on May 31, 1998. An avalanche struck a team attempting the West Crater Rim route at 10:05 a.m. and swept down about 1,250 feet. One climber was killed in the slide and two others seriously injured; the leader of the group, on a separate rope team, also was injured. The party had headed up the mountain despite one to two feet of new snow in the past week, a “high avalanche hazard” warning posted by the U.S. Forest Service, and signs of recent avalanche activity along their route.

According to the Mt. Hood climbing ranger, most of the people on the mountain that day in late May did not carry avalanche transceivers. “Some of these climbers later remarked that they hadn’t considered avalanches to be a problem, as it was late in the season and it was such a beautiful day,” the report says. “But in fact, a secondary maximum in monthly Northwest avalanche fatalities occurs in May, similar to the mid-winter Northwest maximums.”

Read the full ANAC report here.

Rockfall took out this anchor at the Narrows, near Redstone, Colorado, last summer. Photo by Chris Kalous (@enormocast)

IT’S SPRINGTIME! HEADS UP!

Avalanches aren’t the only hazards that trend upward in springtime: Rockfall and loose holds become more frequent at many cliffs in the spring, as the freeze-thaw cycle and heavy precipitation prepares missiles for launching.

Last May, a climber experienced this the hard way during the fifth-class approach to Break on Through at Moore’s Wall, North Carolina. Two weeks of heavy rain had loosened some big holds, and this climber found one of them. His report will be published in ANAC 2021, but you can read it now at the AAC’s publications website.

If you choose not to wear a helmet for shorter climbs, such as sport routes, consider changing this habit for spring and early summer climbs. In addition to the hazards mentioned above, thunderstorms frequently send volleys of rock over cliffs, threatening climbers and belayers alike. Rockfall also may impact fixed gear and anchors: Check before you trust.

THE SHARP END PODCAST

Last summer, Jes Scott and Erica Ellefsen set out on an 80-kilometer high-mountain traverse from Mt. Washington to Flower Ridge in Strathcona Provincial Park, British Columbia. Listen to the latest Sharp End podcast to hear what went wrong during their planned eight-day traverse and how they decided to call for a rescue. The Sharp End podcast is sponsored by the American Alpine Club.

The monthly Accidents Bulletin is supported by adidas Outdoor and the members of the American Alpine Club.

Statement on Bolting Petroglyphs Near Moab, Utah

We unequivocally condemn the recent actions at Sunshine Wall, near Moab, Utah that compromised the integrity of petroglyphs, sacred Indigenous cultural artifacts.

It is essential that climbers understand the significance of petroglyphs, not only as a window into the past but as an ongoing and vital part of Indigenous culture and identity to this day, and are committed to protecting these sacred sites. The cultural and spiritual value of these places cannot be measured, and we firmly support efforts to protect them. We are currently reaching out to our friends and partners in the local and national tribal, climbing, and land management communities to discuss how to best proceed with the current situation and prevent such instances from occurring again.

Signed,

American Alpine Club

Access Fund

Friends of Indian Creek

Salt Lake Climbers Alliance

Western Colorado Climbers’ Coalition

The Prescription—April 2021

LOWERING ERROR – NO STOPPER KNOT

A PERSONAL STORY FROM THE EDITOR IN CHIEF

One of the most common incidents reported in Accidents in North American Climbing is lowering a climber off the end of the rope (specifically, allowing the end of the rope to pass through a belay device, causing the climber to fall to the ground). As the editor of Accidents for the last seven years, I am all too familiar with this accident type. Yet late last year, I allowed it to happen to me.

In sharing this story, the last thing I want to do is blame my belayer. I firmly believe that climbers are largely responsible for our own safety, and, as I’ll explain, I had enough information and know-how to make much better decisions before starting up this route.

The climb was our warm-up on a sunny October day at Staunton State Park in Colorado. The Mountain Project description of this 5.9+ sport route said it was 95 feet high and that you could lower with a 60-meter rope with care. We had brought a fairly new 60-meter rope to the crag. The pitch was obviously long: I couldn’t see the anchor over a bulge up high, and the description said there were 14 protection bolts. But all these clues didn’t prompt me to tie a stopper knot in the belayer’s end of the rope before heading up.

During the long pitch, I made a mental note to tell my belayer to keep an eye on the end of the rope as I lowered off, and I thought the same thing as I rigged the anchor for top-roping. But I couldn’t see the belayer on the ground until I had lowered for 35 or 40 feet, and by then I’d forgotten my plan to warn the belayer to watch the ends.

Three or four feet off the ground, as I was backing down ledges at the base of the climb, the rope end shot through the belayer’s device and I tumbled to the ground, knocking over the belayer and rolling across a stony belay platform. Fortunately, neither of us were injured, but we were both badly shaken.

Did I feel stupid? You bet I did. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve written some form of this sentence in the pages of Accidents: “A stopper knot in the end of the rope would have prevented this accident.” I even urged readers to make a pledge to tie stopper knots in an editorial a couple of years ago. How could I have neglected this basic step? It was complacency, plain and simple.

No one is immune to mistakes. The only way to ensure you’ll have a stopper knot when you need it is to tie one every time. (Or you can tie the belayer’s end to a rope bag, or the belayer can tie in to close the system.) Every time. It feels silly for short pitches, but it forms a routine, so you’ll be prepared when it really counts. Tying the knot also subtly influences your climbing partners and other climbers at the crag; hopefully, they’ll develop their own good habits.

The Mountain Project description for that climb at Staunton has been revised, and now it should be clear that a 70-meter rope (or some easy downclimbing with a 60m) is needed. But ropes shrink, ropes get cut, your partner might have forgotten which rope he brought. A stopper knot is the ultimate shield against bad beta. It’s also a wonderful antidote to complacency.

I got off easy last October, and I’ve finally learned my lesson. Closing the belay system takes only seconds, and there is no downside. So, please, don’t repeat my mistake. Just tie the darned knot.

— Dougald MacDonald, Editor

Back in 1982, Jean Muenchrath and her partner summited Mt. Whitney as the culmination of a winter ski traverse of the John Muir Trail. On the summit they were caught in a severe snow and lightning storm. During their attempt to escape the mountain, her partner took a long sliding fall, and then Jean, trying to get down herself, also fell and bounced down through rocks for more than 150 feet, enduring massive trauma. Listen to this episode to hear a true story of tenacity and survival. The Sharp End podcast is sponsored by the American Alpine Club.

MEET THE RESCUERS

Dr. Christopher Van Tilburg, medical director for Mt. Hood rescue teams, gives us an update on climbing and COVID-19.

Home town: Hood River, Oregon

Volunteer and professional life: I’m a rescuer and medical director for Hood River Crag Rats and medical director for Portland Mountain Rescue, Pacific Northwest SAR, and Clackamas County SAR. Basically all the areas around Mt. Hood. My day job is working for Providence Hood River Memorial Hospital in clinic and the emergency room, but also at the Mount Hood Meadows ski resort (21 years!). Finally, I’m the Hood River County medical examiner and public health officer, which is a good complement for public safety and SAR work.

How did you first become interested in search and rescue?

I grew up with parents who spent lots of time volunteering in the local community and abroad. They were involved in the Friendship Force, a person-to-person exchange program, and Christian Medical Society. Initially I became interested in wilderness medicine through doing medical relief programs. Then, in medical school, I realized it was a way of merging my passion with the outdoors, medicine, and my interest in volunteering.

Any personal climbing accidents or close calls?

I almost died on Mt. Hood in an inbounds ski accident. One weekend we had six inches of rain followed by freezing temps, so the snowpack froze solid. Then we had a foot of snow. I fell and ended up having emergency surgery. It put things in perspective: Things can go bad at any time, in an instant.

What sort of work are you doing with SAR teams in relation to COVID-19?

I put together or assisted with most COVID-19 protocols for the teams where I am medical director. It was particularly challenging because recommendations changed as the pandemic evolved.

Given that most of our readers are climbing outdoors, how worried do they need to be about catching or transmitting the virus?

Outdoor activity is very low risk. Probably the biggest risk is driving in a closed vehicle to the mountain or crag or sharing a tent. I’ve been vaccinated since very early, but I—and my ski buddies—still wear a mask on the commute up the mountain. Vaccination limits risk, wearing a mask limits risk, washing hands and trying to keep your distance limits risk. Employ these three things and you’ll be much safer.

What other precautions can climbers and mountaineers take?

Forming a pod of people with whom you climb regularly will help. Then, do a quick safety check before leaving the house to pick up your buddy: Are you sick? Have you been exposed to someone sick?

With vaccination increasing and so many states opening up, even as COVID variants are spreading, how should climbers adjust their risk assessment during the spring and summer months?

Right now, keep wearing a mask. We don’t know yet about variants, how effective the vaccine will be. We also have many cases of people vaccinated but still getting COVID-19. So, I’d say, don’t be too eager to stop wearing the mask.

Share Your Story: The deadline for the 2021 edition of Accidents in North American Climbing is April 30. If you were involved in a climbing accident or rescue in 2020, consider sharing the lessons with other climbers. Let’s work together to reduce the number of accidents. Reach us at [email protected].

The monthly Accidents Bulletin is supported by adidas Outdoor and the members of the American Alpine Club.

The Music Stopped: A Story from the Climbing Grief Fund

The Climbing Grief Grant offers financial support for individuals directly impacted by grief, loss, and/or trauma related to climbing, ski mountaineering, or alpinism.

This exhibit explores the experience of grief from a personal perspective. In this case, this exploration of grief reflects on the death of AAC employee Dillon Blanksma, after he fell from Broadway Ledge on Longs Peak. You can learn more about the Climbing Grief Fund here.

*This story is best told with the help of vibrant and dynamic photography. Dive into this Spark Exhibit to see these photos come alive alongside this story.

The American Alpine Club launches Climb United initiative

The American Alpine Club (AAC) is proud to announce Climb United, a new initiative centered around convening climbers, climbing organizations, and industry brands to transform the culture around inclusivity. Current partners of the Climb United project include REI, Eddie Bauer, Mammut, The North Face, and Patagonia.

We are excited to launch the program with a draft of Principles and Guidelines for Publishing Climbing Route Names developed by the Route Name Task Force, composed of a group of publishers and climbing community members. The Guiding Principles will serve to establish an agreed-upon philosophy toward publishing climbing route names, while the Guidelines provide an evaluation and management system for addressing discriminatory route names. The AAC will host a public forum on the draft guidelines on April 21 at 6 p.m. MDT to engage the community and encourage questions and feedback. You can also provide feedback on the draft guidelines via this survey.

Participants in the working group include Alpinist Magazine, Climbing Magazine, the Climbing Zine, Gripped Magazine, Mountain Project, Mountaineers Books, Sharp End Publishing, and Wolverine Publishing.

In February of this year, the AAC surveyed climbers and found that over 82% of respondents believe it is important that the climbing community address diversity and inclusion within the sport. Additionally, over 77% of respondents believe it is important to address discriminatory route names to make climbing more welcoming to all people, regardless of race, ethnicity, national origin, age, range of abilities, sexual orientation, or gender identity.

AAC CEO Mitsu Iwasaki described the importance of the Climb United project, "Our climbing culture, which I have been a part of and contributor to for nearly 30 years, has, without mal-intent, created spaces that have been hurtful and uninviting to many. I am grateful through Climb United, we (brands, publishers, and climbers) have come together with an abundance of humility to engage in difficult and necessary conversations to evolve, elevate, and ensure a vibrant future for climbing."

The AAC recently hired Climb United Director Cody Kaemmerlen to help guide the project. Kaemmerlen shared his excitement about joining the initiative as the Climb United Director, “I’m honored to serve the climbing community that I care so deeply for and to help all folks find their way to this sport. The crags, mountains, and remote summits continue to bring me a lifetime of memories and relationships. I understand the enormity of the barriers that exist, and I’m excited to push extra hard to help break them down.”

Climbers can also follow along with Climb United’s progress via a timeline of past projects and future goals.

Learn more about Climb United at climbunited.org

The Prescription - April 2021

Just tie the darned knot! Photo by Ron Funderburke.

The Prescription - April 2021

LOWERING ERROR – NO STOPPER KNOT

A PERSONAL STORY FROM THE EDITOR IN CHIEF

One of the most common incidents reported in Accidents in North American Climbing is lowering a climber off the end of the rope (specifically, allowing the end of the rope to pass through a belay device, causing the climber to fall to the ground). As the editor of Accidents for the last seven years, I am all too familiar with this accident type. Yet late last year, I allowed it to happen to me.

In sharing this story, the last thing I want to do is blame my belayer. I firmly believe that climbers are largely responsible for our own safety, and, as I’ll explain, I had enough information and know-how to make much better decisions before starting up this route.

The climb was our warm-up on a sunny October day at Staunton State Park in Colorado. The Mountain Project description of this 5.9+ sport route said it was 95 feet high and that you could lower with a 60-meter rope with care. We had brought a fairly new 60-meter rope to the crag. The pitch was obviously long: I couldn’t see the anchor over a bulge up high, and the description said there were 14 protection bolts. But all these clues didn’t prompt me to tie a stopper knot in the belayer’s end of the rope before heading up.

During the long pitch, I made a mental note to tell my belayer to keep an eye on the end of the rope as I lowered off, and I thought the same thing as I rigged the anchor for top-roping. But I couldn’t see the belayer on the ground until I had lowered for 35 or 40 feet, and by then I’d forgotten my plan to warn the belayer to watch the ends.

Photo of the author by Mark Hammond

Three or four feet off the ground, as I was backing down ledges at the base of the climb, the rope end shot through the belayer’s device and I tumbled to the ground, knocking over the belayer and rolling across a stony belay platform. Fortunately, neither of us were injured, but we were both badly shaken.

Did I feel stupid? You bet I did. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve written some form of this sentence in the pages of Accidents: “A stopper knot in the end of the rope would have prevented this accident.” I even urged readers to make a pledge to tie stopper knots in an editorial a couple of years ago. How could I have neglected this basic step? It was complacency, plain and simple.

No one is immune to mistakes. The only way to ensure you’ll have a stopper knot when you need it is to tie one every time. (Or you can tie the belayer’s end to a rope bag, or the belayer can tie in to close the system.) Every time. It feels silly for short pitches, but it forms a routine, so you’ll be prepared when it really counts. Tying the knot also subtly influences your climbing partners and other climbers at the crag; hopefully, they’ll develop their own good habits.

The Mountain Project description for that climb at Staunton has been revised, and now it should be clear that a 70-meter rope (or some easy downclimbing with a 60m) is needed. But ropes shrink, ropes get cut, your partner might have forgotten which rope he brought. A stopper knot is the ultimate shield against bad beta. It’s also a wonderful antidote to complacency.

I got off easy last October, and I’ve finally learned my lesson. Closing the belay system takes only seconds, and there is no downside. So, please, don’t repeat my mistake. Just tie the darned knot.

— Dougald MacDonald, Editor

THE SHARP END PODCAST

Back in 1982, Jean Muenchrath and her partner summited Mt. Whitney as the culmination of a winter ski traverse of the John Muir Trail. On the summit they were caught in a severe snow and lightning storm. During their attempt to escape the mountain, her partner took a long sliding fall, and then Jean, trying to get down herself, also fell and bounced down through rocks for more than 150 feet, enduring massive trauma. Listen to this episode to hear a true story of tenacity and survival. The Sharp End podcast is sponsored by the American Alpine Club.

MEET THE RESCUERS

Dr. Christopher Van Tilburg, medical director for Mt. Hood rescue teams, gives us an update on climbing and COVID-19.

Home town: Hood River, Oregon

Christopher Van Tilburg near Everest Base Camp, Nepal.

Volunteer and professional life: I’m a rescuer and medical director for Hood River Crag Rats and medical director for Portland Mountain Rescue, Pacific Northwest SAR, and Clackamas County SAR. Basically all the areas around Mt. Hood. My day job is working for Providence Hood River Memorial Hospital in clinic and the emergency room, but also at the Mount Hood Meadows ski resort (21 years!). Finally, I’m the Hood River County medical examiner and public health officer, which is a good complement for public safety and SAR work.

How did you first become interested in search and rescue?

I grew up with parents who spent lots of time volunteering in the local community and abroad. They were involved in the Friendship Force, a person-to-person exchange program, and Christian Medical Society. Initially I became interested in wilderness medicine through doing medical relief programs. Then, in medical school, I realized it was a way of merging my passion with the outdoors, medicine, and my interest in volunteering.

Any personal climbing accidents or close calls?

I almost died on Mt. Hood in an inbounds ski accident. One weekend we had six inches of rain followed by freezing temps, so the snowpack froze solid. Then we had a foot of snow. I fell and ended up having emergency surgery. It put things in perspective: Things can go bad at any time, in an instant.

What sort of work are you doing with SAR teams in relation to COVID-19?

I put together or assisted with most COVID-19 protocols for the teams where I am medical director. It was particularly challenging because recommendations changed as the pandemic evolved.

Given that most of our readers are climbing outdoors, how worried do they need to be about catching or transmitting the virus?

Outdoor activity is very low risk. Probably the biggest risk is driving in a closed vehicle to the mountain or crag or sharing a tent. I’ve been vaccinated since very early, but I—and my ski buddies—still wear a mask on the commute up the mountain. Vaccination limits risk, wearing a mask limits risk, washing hands and trying to keep your distance limits risk. Employ these three things and you’ll be much safer.

What other precautions can climbers and mountaineers take?

Forming a pod of people with whom you climb regularly will help. Then, do a quick safety check before leaving the house to pick up your buddy: Are you sick? Have you been exposed to someone sick?

With vaccination increasing and so many states opening up, even as COVID variants are spreading, how should climbers adjust their risk assessment during the spring and summer months?

Right now, keep wearing a mask. We don’t know yet about variants, how effective the vaccine will be. We also have many cases of people vaccinated but still getting COVID-19. So, I’d say, don’t be too eager to stop wearing the mask.

Share Your Story: The deadline for the 2021 edition of Accidents in North American Climbing is April 30. If you were involved in a climbing accident or rescue in 2020, consider sharing the lessons with other climbers. Let’s work together to reduce the number of accidents. Reach us at [email protected].

The monthly Accidents Bulletin is supported by adidas Outdoor and the members of the American Alpine Club.

The Prescription—March 2021

GROUND FALL – INADEQUATE PROTECTION

COOPER’S ROCK STATE FOREST, WEST VIRGINIA

Mike had set up a video camera to record what he hoped would be an onsight send of a 5.12 route at Cooper’s Rock. The first gear placement is marked. The route is usually top-roped. Video capture courtesy of Mike Paugh

On October 4, Sarah Smith and I (Mike Paugh, 38) were searching for areas to bring clients with my new guide service, Ascension Climbing Guides. While exploring, we were also climbing routes in the area. At the Roof Rocks, about 2 p.m., I racked up to attempt Upchouca (5.12a/b), which begins with an unprotected V5 start. I knew the route was in my wheelhouse of climbing fitness but also at the peak of my climbing limits. I felt confident about the send. I rehearsed the opening moves 10 to 12 times, trying to find my sequence to the hero jug about 15 feet up.

I set off one last time, committing to the boulder problem and fully aware there was a point of no return where I could not jump off without getting injured. I felt gassed and pumped immediately after making it through the crux, probably from the numerous attempts to figure out my sequence. Unfortunately, the placement I had spotted from the ground for my first piece of protection turned out to be complete garbage.

Realizing that I was in trouble, I continued upward and found an excellent horizontal seam. I placed a yellow Metolius TCU up to the trigger, with all three lobes fully engaged, and clipped it using an alpine draw. Breathing a sigh of relief, I asked my belayer, Sarah, to take me. The cam held and I proceeded to shake out my arms. The climbing above looked to ease up significantly, and I identified a couple solid gear placements.

As soon as I shifted my weight to the left to continue up the route, the TCU blew from the rock with the sound of a 12-gauge shotgun. When it popped, a piece of rock hit me in the face as I began to fall. Everything sped up, and the next thing I remember is hitting the ground and screaming in pain. I suffered an open fracture of my left tibia and fibula. Thankfully, there was a party of four climbers nearby who responded to Sarah’s call for help until EMS arrived.

ANALYSIS

I had three surgeries to repair the damage and later remove the external fixation device attached to my leg. I’ve been doing great with my recovery, and I’ve started climbing again in the gym.

Looking back, I’ve thought about the risk assessment I should have made before attempting the route. Given the hard, bouldery crux in the first 15 to 18 feet of this route and the rocky landing below it, I should have placed bouldering pads at the base of the climb, treating it like a highball boulder problem. Protecting the landing zone should have been priority number one, especially for a ground-up, onsight attempt. Once I reached the jug hold past the crux, I was in a no-return, no-fall zone, especially without any pad protection.

I’ve also realized I should have considered setting up a top-rope to rehearse the route, due to its PG-13 rating and not being able to assess gear placements adequately from the ground. Had I done so, I could have climbed the route with little to no consequences, assessing the rock quality (which was a little chossy in the crack) and gear placements before leading the climb. I also could have backed up the single TCU with another placement before asking Sarah to take my weight.

I am extremely grateful to the group of young climbers who kept me calm and called 911, to Jan Dzierzak, the Cooper’s Rock superintendent, to Adam Polinski, who showed the rescue group the easiest way out during the extraction, to the local rescue volunteers and professionals who responded to the call, and to the highly skilled orthopedic surgery and physical therapy staff at WVU–Ruby Memorial Hospital. I have received amazing support from my climbing community, family, and friends, not just locally but also nationally. (Source: Mike Paugh.)

Mike’s family and friends set up a Go Fund Me page to offset expenses that weren’t covered by his health insurance.

PIEPS BEACONS TO BE RECALLED

Black Diamond Equipment announced March 3 that it is working under the guidance of the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission and Health Canada to initiate a Fast Track voluntary product recall for PIEPS DSP avalanche transceivers. Black Diamond Equipment is the North American distributor for PIEPS. The announcement pertains to the PIEPS DSP Pro, DSP Pro Ice, and DSP Sport avalanche transceivers.

The recall is in response to users’ reports the beacons can accidentally switch out of transmit mode during use. The recall is already underway in Europe and elsewhere, but Black Diamond must work with government agencies to begin the formal recall in North America. Details will be announced soon. In the meantime, alternative beacons should be used.

EUROPEAN ACCIDENT STUDIES

Two recent papers on the nature and causes of rock climbing and mountaineering accidents in Europe are available to download:

• Mountaineering incidents in France: analysis of search and rescue interventions on a 10-year period, published in the Journal of Mountain Science. The download link (a fee or institutional access required) is here.

• Rock Climbing Emergencies in the Austrian Alps: Injury Patterns, Risk Analysis and

Preventive Measures, published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. The full article can be downloaded (no charge) from the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Incidentally, two of the lead authors on these studies, Maud Vanpoulle (France) and Laura Tiefenthaler (Austria), are very accomplished alpine climbers. Tiefenthaler climbed both Cerro Torre and Fitz Roy last season, and Vanpoulle’s climbs in Chile’s Cordillera Darwin with the French national women’s mountaineering team appeared in the 2019 American Alpine Journal.

THE SHARP END

Near misses are greatly under-reported in climbing and backcountry skiing, yet they are plentiful. What leads them to be under-reported and how can they help climbers avoid future accidents? In Episode 62 of the Sharp End, Joel Reid, the Washington Program Director at the Northwest Outward Bound School, and Steve Smith, from Experiential Consulting, chat with Ashley about the importance of reporting and studying near misses. The Sharp End podcast is sponsored by the American Alpine Club.

THE ROAD TO RECOVERY

Colorado-based pro climber Molly Mitchell suffered a serious accident on October 1 last year, falling to the ground after ripping four pieces of gear from her project: a traditional ascent (skipping the bolts) on the 5.13c/d route Crank It in Boulder Canyon. She fractured two vertebrae in her lower back. Understandably, both the physical and psychological recovery have been tough. And so, we were happy to see her post on March 4 celebrating a return to hard trad climbing. Though few can climb as hard as Molly, many will identify with her feelings following a damaging fall. Highlights from her post are reproduced below; click on the photo to read the whole post.

🙏 Yesterday was big for me. So happy to have sent “Bone Collector” (aka Bone Crusher), a 5.12 trad line at The Quarry in Golden, CO…. It’s been 5 months since I broke my back taking a ground fall in Boulder Canyon. 3 months since I got out of the back brace.

I have to say that the last couple months have been incredibly hard for me. Maybe even harder than the 2 months I spent in the back brace. Not only did I not realize the physical limitations the soft tissue in my back would still have, but my mental game has been all over the place. Earlier in February, I was crying almost every time I led a trad route and having intense anxiety attacks. I didn’t realize the long term effect the trauma of the accident would have on me. I have said to my friends: I feel like a different person and it’s made me feel like I’ve lost my identity.

I started working on this route at the end of January. The route takes good gear, but I still had such a hard time trusting the gear on anything, and even more importantly, trusting myself…. For a while, and still sometimes, even weighting a piece at all was so hard because my body would just still recall the feeling of the gear ripping from my accident…. It’s been a battle.

Yesterday was the first time I felt in the zone again while climbing since the accident. I was still very nervous and scared, but I was able to push through…. I’m so proud of myself. I don’t feel confident saying that often because my anxiety doesn’t want me to come across like I have an ego. But this one meant a lot 🥺. Thank you to everyone who has been incredibly supportive & helpful the last couple months.

Share Your Story: The deadline for the 2021 edition of Accidents in North American Climbing is not far off. If you were involved in a climbing accident or rescue in 2020, consider sharing the lessons with other climbers. Let’s work together to reduce the number of accidents. Reach us at [email protected].

The monthly Accidents Bulletin is supported by adidas Outdoor and the members of the American Alpine Club.

The Prescription - March 2021

Mike had set up a video camera to record what he hoped would be an onsight send of a 5.12 route at Cooper’s Rock. The first gear placement is marked. The route is usually top-roped. Video capture courtesy of Mike Paugh

The Prescription - March 2021

GROUND FALL – INADEQUATE PROTECTION

COOPER’S ROCK STATE FOREST, WEST VIRGINIA

On October 4, Sarah Smith and I (Mike Paugh, 38) were searching for areas to bring clients with my new guide service, Ascension Climbing Guides. While exploring, we were also climbing routes in the area. At the Roof Rocks, about 2 p.m., I racked up to attempt Upchouca (5.12a/b), which begins with an unprotected V5 start. I knew the route was in my wheelhouse of climbing fitness but also at the peak of my climbing limits. I felt confident about the send. I rehearsed the opening moves 10 to 12 times, trying to find my sequence to the hero jug about 15 feet up.

I set off one last time, committing to the boulder problem and fully aware there was a point of no return where I could not jump off without getting injured. I felt gassed and pumped immediately after making it through the crux, probably from the numerous attempts to figure out my sequence. Unfortunately, the placement I had spotted from the ground for my first piece of protection turned out to be complete garbage.

Realizing that I was in trouble, I continued upward and found an excellent horizontal seam. I placed a yellow Metolius TCU up to the trigger, with all three lobes fully engaged, and clipped it using an alpine draw. Breathing a sigh of relief, I asked my belayer, Sarah, to take me. The cam held and I proceeded to shake out my arms. The climbing above looked to ease up significantly, and I identified a couple solid gear placements.

As soon as I shifted my weight to the left to continue up the route, the TCU blew from the rock with the sound of a 12-gauge shotgun. When it popped, a piece of rock hit me in the face as I began to fall. Everything sped up, and the next thing I remember is hitting the ground and screaming in pain. I suffered an open fracture of my left tibia and fibula. Thankfully, there was a party of four climbers nearby who responded to Sarah’s call for help until EMS arrived.

ANALYSIS

I had three surgeries to repair the damage and later remove the external fixation device attached to my leg. I’ve been doing great with my recovery, and I’ve started climbing again in the gym.

Looking back, I’ve thought about the risk assessment I should have made before attempting the route. Given the hard, bouldery crux in the first 15 to 18 feet of this route and the rocky landing below it, I should have placed bouldering pads at the base of the climb, treating it like a highball boulder problem. Protecting the landing zone should have been priority number one, especially for a ground-up, onsight attempt. Once I reached the jug hold past the crux, I was in a no-return, no-fall zone, especially without any pad protection.

I’ve also realized I should have considered setting up a top-rope to rehearse the route, due to its PG-13 rating and not being able to assess gear placements adequately from the ground. Had I done so, I could have climbed the route with little to no consequences, assessing the rock quality (which was a little chossy in the crack) and gear placements before leading the climb. I also could have backed up the single TCU with another placement before asking Sarah to take my weight.

I am extremely grateful to the group of young climbers who kept me calm and called 911, to Jan Dzierzak, the Cooper’s Rock superintendent, to Adam Polinski, who showed the rescue group the easiest way out during the extraction, to the local rescue volunteers and professionals who responded to the call, and to the highly skilled orthopedic surgery and physical therapy staff at WVU–Ruby Memorial Hospital. I have received amazing support from my climbing community, family, and friends, not just locally but also nationally. (Source: Mike Paugh.)

Mike’s family and friends set up a Go Fund Me page to offset expenses that weren’t covered by his health insurance.

EUROPEAN ACCIDENT STUDIES

Two recent papers on the nature and causes of rock climbing and mountaineering accidents in Europe are available to download:

• Mountaineering incidents in France: analysis of search and rescue interventions on a 10-year period, published in the Journal of Mountain Science. The download link (a fee or institutional access required) is here.

• Rock Climbing Emergencies in the Austrian Alps: Injury Patterns, Risk Analysis and

Preventive Measures, published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. The full article can be downloaded (no charge) from the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Incidentally, two of the lead authors on these studies, Maud Vanpoulle (France) and Laura Tiefenthaler (Austria), are very accomplished alpine climbers. Tiefenthaler climbed both Cerro Torre and Fitz Roy last season, and Vanpoulle’s climbs in Chile’s Cordillera Darwin with the French national women’s mountaineering team appeared in the 2019 American Alpine Journal.

THE SHARP END

Near misses are greatly under-reported in climbing and backcountry skiing, yet they are plentiful. What leads them to be under-reported and how can they help climbers avoid future accidents? In Episode 62 of the Sharp End, Joel Reid, the Washington Program Director at the Northwest Outward Bound School, and Steve Smith, from Experiential Consulting, chat with Ashley about the importance of reporting and studying near misses. The Sharp End podcast is sponsored by the American Alpine Club.

THE ROAD TO RECOVERY

Colorado-based pro climber Molly Mitchell suffered a serious accident on October 1 last year, falling to the ground after ripping four pieces of gear from her project: a traditional ascent (skipping the bolts) on the 5.13c/d route Crank It in Boulder Canyon. She fractured two vertebrae in her lower back. Understandably, both the physical and psychological recovery have been tough. And so, we were happy to see her post on March 4 celebrating a return to hard trad climbing. Though few can climb as hard as Molly, many will identify with her feelings following a damaging fall. Highlights from her post are reproduced below; click on the photo to read the whole post.

🙏 Yesterday was big for me. So happy to have sent “Bone Collector” (aka Bone Crusher), a 5.12 trad line at The Quarry in Golden, CO…. It’s been 5 months since I broke my back taking a ground fall in Boulder Canyon. 3 months since I got out of the back brace.

I have to say that the last couple months have been incredibly hard for me. Maybe even harder than the 2 months I spent in the back brace. Not only did I not realize the physical limitations the soft tissue in my back would still have, but my mental game has been all over the place. Earlier in February, I was crying almost every time I led a trad route and having intense anxiety attacks. I didn’t realize the long term effect the trauma of the accident would have on me. I have said to my friends: I feel like a different person and it’s made me feel like I’ve lost my identity.

I started working on this route at the end of January. The route takes good gear, but I still had such a hard time trusting the gear on anything, and even more importantly, trusting myself…. For a while, and still sometimes, even weighting a piece at all was so hard because my body would just still recall the feeling of the gear ripping from my accident…. It’s been a battle.

Yesterday was the first time I felt in the zone again while climbing since the accident. I was still very nervous and scared, but I was able to push through…. I’m so proud of myself. I don’t feel confident saying that often because my anxiety doesn’t want me to come across like I have an ego. But this one meant a lot 🥺. Thank you to everyone who has been incredibly supportive & helpful the last couple months.

Share Your Story: The deadline for the 2021 edition of Accidents in North American Climbing is not far off. If you were involved in a climbing accident or rescue in 2020, consider sharing the lessons with other climbers. Let’s work together to reduce the number of accidents. Reach us at [email protected].

The monthly Accidents Bulletin is supported by adidas Outdoor and the members of the American Alpine Club.

AAC Announces 2021 Cutting Edge Grant Winners

Photo credits: Kurt Ross of Jess Roskelley on Baba Hussein, 2018 Cutting Edge Grant Recipient

The American Alpine Club and Black Diamond are pleased to announce the 2021 Cutting Edge Grant recipients. The Cutting Edge Grant continues the Club’s 100-year tradition and seeks to fund individuals planning expeditions to remote areas featuring unexplored mountain ranges, unclimbed peaks, difficult new routes, first free ascents, or similar world-class pursuits. Objectives featuring a low-impact style and leave-no-trace mentality are looked upon with favor. For the 2021 grant cycle, Black Diamond is a proud sponsor and partner in supporting cutting-edge alpinism. $25,000 has been awarded to six recipients.

Ryan Driscoll will receive a grant to attempt the North Face (aka The Medusa Face) of Mount Neacola in Lake Clark National Park, Alaska.

Nick Aiello-Popeo will receive a grant to attempt the unclimbed 6,000-vertical-foot West Face of Ganesh I (7,422 meters/24,350 feet; also called Yangra). This Himalayan giant is the highest peak in the Ganesh Himal in eastern Nepal, on the Tibetan border. The mountain has only seen one recoded ascent, from the north in 1955. Himalayan historian Damien Gildea described the objective as “one of the biggest unclimbed faces in the Himalaya.”

Matthew Cornell will receive a grant to attempt the West Face of the North Horseman, and the West Face of Pyramid Peak in Alaska's Revelation Mountains.

Vitaliy Musiyenko will receive a grant to attempt new routes on the North Face of Melanphulan (6,573 M) and the South Face of Nuptse in the Khumbu Region. Musiyenko had previously been awarded the Cutting Edge Grant in 2020, but the expedition was postponed due to COVID-19 travel restrictions.

And lastly, Sam Hennessey will receive a grant to attempt the East Face of Jannu East.

The Cutting Edge Grant is sponsored by Black Diamond, who’s equipment has helped climbers and alpinist to reach their summits for decades. Black Diamond is an integral partner in supporting climbers of all abilities and disciplines, with a long history of supporting climbers and their dreams through grants like the Cutting Edge Grant. Applications for the Cutting Edge Grant are accepted each year from October 1st through November 30th.

For more information, visit americanalpineclub.org/cutting-edge-grant

For more information on Black Diamond, visit blackdiamondequipment.com

“A Great Many Years”—Honorary President William Lowell Putnam

The American Alpine Club’s Honorary President, William Lowell Putnam gave this speech at the Club’s 2011 Board Meeting in Flagstaff, Arizona. We’ve reproduced it here because it’s a fantastic speech, broad in scope and incredibly rich in Club history—and mountaineering history.

William Putnam.

It’s been a great many years since I was asked to address a general meeting of this organization. Discounting the speech that my dear wife delivered for me a few years ago at the time of our Centennial, the only other time was in December of 1944, when I was a lot younger and a 2nd Lieutenant fresh from Fort Benning on my way to rejoin the 10th Mountain Division, of which I had been one of its notorious “three letter” men. The meeting was in New York City, Doctor Thorington was the president, and the Board had just admitted me to membership. I talked briefly about the first ascent of the 4000-foot volcano on Kiska, which I had trudged across the tundra to make in October of 1943, with Harley Fetzer and the late Carl Fiebelkorn, who went AWOL with me—after all, we were mountain troopers, and building a pier out into Kiska Harbor was just not our thing.

I guess I’m grateful to be able to be asked back—but it took a very special engineer to arrange it, all these years later—thank you, Steve [Swenson]. At my present advanced age—I was barely 20 then—you’ll have to pardon me if I seem to repeat myself occasionally; but since I know a good many of those here present and most of our newer members are unfamiliar with a lot of Club history, some of the lines I will offer you this evening, will surely appear as new.

However, it is NOT true, as past president Jim Frush stated in our Club’s centennial publication, that I had the pleasure of knowing many of our founders. Indeed, I suspect a good many of them would surely have felt that making my youthful acquaintance was NOT a pleasure. After all I did organize the only proxy fight against Club management, in an effort to get our annual meeting rotated around the country to exotic locales such as Berzerkeley, Las Vegas, and Bend, in doing which I was joined by one past president and two subsequent honorary members. However, I did share an office with Professor Fay, our first, second and sixth president, albeit there was a gap of 18 years between his death and my arrival in Barnum Museum at Tufts University. A few years after I left there, the whole place burned down, anyway, Phineas Barnum’s Jumbo and all.

It is fitting that we assemble in Flagstaff for this brief history lesson on The American Alpine Club. For it was here, in 1896 that a founding member of this Club, Andrew Ellicott Douglas, the father of the science of dendrochronology, selected the site for Dr. Lowell’s Observatory. Furthermore it was one of Lowell’s subsequent scientists, Dr. Henry Lee Giclas, who determined, most of a century later, that the world’s highest summit, measured from the center of the Earth, is not Mount Everest, after all; it is Huascaran, in Peru.

* * *

Angelo Heilprin, Founder of the American Alpine Club. Click the pic to see the other photos from this speech.

The American Alpine Club was founded by Professor Angelo Heilprin, a notable vulcanologist for whom Admiral Peary named a tide-water glacier in west-central Greenland. Heilprin was associated with the learned folk in the City of Brotherly Love, as were many of our founding members—which is the reason this Club was incorporated in that Commonwealth. Heilprin was also the heroic scientist who descended into the caldera of Mont Pelee on Martinique to investigate the basaltic monolith that was extruded after the massive explosion of 1902. He had been born in Hungary, of parents who fled from persecution in Russia to Poland and finally to America.

Angelo Heilprin, Founder of the American Alpine Club.

About the time of the vernal equinox of 1901—that’s more than 110 years ago—Dr. Heilprin mailed a notice (for two cents apiece in postage) of a meeting to be held on 9 May in the rooms of the Geographical Society of Philadelphia, to consider the formation of an alpine society. On that fateful Thursday afternoon, twelve men, including our first President, our first two Vice-presidents, our first Secretary and our first Treasurer, along with our first four Counselors, constituted themselves as the Committee of Organization and proceeded to elect a bunch of members. We are honored to have with us tonight the grandson of that treasurer, Professor of Hydrology Henry James Vaux, Jr, emeritus from the University of California at Berkeley.

Along with Professor Heilprin, whose great, great nephew is a valued member, the other Vice-president of our Club was George Davidson, a native of Nottingham in the old country. He was a distinguished geologist and geodesist, a friend of philanthropist James Lick, who did the primary surveying in coastal Alaska, where he particularly distinguished himself in 1867 in making the first ascent of the volcano Makushin on Unalaska Island. That first ascent was not the spectacular part of the climb—many of us have done such things—the spectacular part was in not overstating the height of the mountain. His aneroid barometer called it some 1139 feet lower than it really is.

We elected our third president, a Scotsman named Muir from California (the patron saint of conservation) when Professor Fay gave up the mantle, and we’ve been led quite capably by a number of Californians since then, the very best of whom is seated right down here—Nicholas Bayard Clinch, in my opinion of our history—adjusted for inflation of both dollars and egos—the Club’s foremost expedition leader, wisest councillor, and greatest benefactor. They don’t make many like Nick; he really should have been elected to my position, but I wasn’t asked for my opinion when the Board made the decision as to who would replace Henry Snow Hall, Jr and Robert Hicks Bates.

The new club put on a fancy dinner in New York on Tuesday, 28 May, 1907, for Luigi Amadeo, di Savoie/Aosta, the celebrated Duke of the Abruzzi, who preceded several of tonight’s very special guests in being elected to Honorary Membership. The Duke, a cousin of the King of Italy, commanded the Italian Navy during much of the Great War; however, he died in 1933 doing humanitarian work at a place that later became unhappily well known to younger members of the 10th Mtn Division than myself, a town in east Africa called Mogodishu.

1907 was the same year that we began the publication of a series of quarto-sized, illustrated monographs, collectively entitled—Alpina Americana—and ostensibly meant to go on almost forever, but of which only three issues were ever printed and delivered to the membership. These were: The High Sierra by Joseph Nisbet LeConte; The Rocky Mountains of Canada by Charles Ernest Fay; and The Mountains of Alaska, by Alfred Hulse Brooks. Today, these three publications are treasured possessions of those who joined the Club prior to about 1950, when we finally ran out of the press run.

I am, however, a suitably distant relative of New York’s Superior Court Justice Harrington Putnam, our fourth president—we have a common ancestor, twelve generations back, who left Ashton-Abbots in the old country and showed up at Salem in 1636. When the judge took office, a century ago, this club had 67 dues-paying members and 11 Honorary Members—those whom our founders believed to be examples for others to emulate—over half of whom had made their most significant mark in polar exploration but less than half of whom were American citizens. They were:

• The Duke of the Abruzzi, of K2 and St. Elias fame, whose party under co-leader Captain Umberto Cagni established a ‘farthest north’ in 1896;

• James, Lord Bryce no alpinist at all, but an historian, scholar and widely admired British Ambassador to the United States;

• John Norman Collie pioneer of the Canadian Rockies and professor of organic chemistry at University College in London;

• Sir William Martin, Lord Conway of Allington, artist, Antarctic and Andean explorer;

• The Reverend William Augustus Brevoort Coolidge, American-born scholar of the Alps and editor of The Alpine Journal;

• General Adolphus Washington Greely, leader of the Lady Franklin Bay Arctic Expedition, of 1881-84, and hero of the San Francisco earthquake of 1906;

• Admiral George Wallace Melville, Chief Engineer of the ill-fated ship, Jeannette, then rescuer of Greely, and architect of America’s Great White Fleet;

• Admiral Robert Edwin Peary who may—or very well may not—have been first to attain the North Pole, in 1906;

• Honorable Theodore Roosevelt god-father, if not father, of the Conservation movement in America;

• Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton author and heroic Antarctic explorer of great note; and,

• Edward Whymper, Esq. English engraver, climber and explorer, who made the first serious report on the illnesses of High Altitude , but was never so honored by his peers in England.

I wonder what any of those men would make of our special guests this evening or the likes of Yvon Chouinard, our most generous innovator, or our Jim McCarthy, the Club’s eminence grise, whose fine, though often Machiavellian, hand has been behind many of our Club’s better accomplishments in my lifetime.

Interestingly, in our more than a century of existence, we have honored a lot of Americans; several Canadians, a dozen Brits, several French, a few Italians, Russians and Japanese, even an Aussie and a South African; but not one single German has ever been elected to honorary membership. The closest we have come was the election of a Dresdener, Fritz Hermann Ernst Wiessner who became an American citizen in 1935, after two decades of distinguished high-angle and high-altitude inspiration in Europe and Asia. The election of Fritz in 1967 was a landmark in Club history, for thereafter, the stranglehold on our affairs by the Anglo-phyllic “Eastern WASP Establishment” came to a rapid and unlamented end.

We have not followed The Alpine Club’s tradition by electing several of our past presidents to Honorary status—that parent organization assumes that election to its presidency is honour enough for anyone. A good number of these folk are here tonightand, since I am the next to senior such animal, and have the mike, I would like our past presidents to stand as I call their names so that we can then make it clear we are pleased they can all still do so. In order of seniority, these other ghosts of our Christmas past are: Nicholas Bayard Clinch—me—James Francis Henriot—Thomas Callander Price Zimmermann—Robert Wallace Craig—James Peter McCarthy—Glenn Edward Porzak—John Edward Williamson—Louis French Reichardt—AlisonKeithOsius (our first lady)—Curtis James Frush—Mark Alan Richey—andJames UgoDonini. Their services to mountaineering have often been greater after leaving—or perhaps because of leaving—the club’s presidency.

* * *

Fritz Hermann Ernst Wiessner—Honorary Club Member. To see other photos from this speech, click the photo to visit the gallery.

This Club’s greatest scholar of alpinism was an ophthalmologist by profession, as was his father before him, James Monroe ‘Roy’ Thorington with whom I never really got along, though we collaborated (sort of) in his final guidebook endeavor to the Rocky Mountains of Canada. Unfortunately for our potential friendship, Roy was close with one of the Club’s lesser sung, but greater blowhards, the man who fouled up the 1939 K2 Expedition, the late Oliver Eaton Cromwell, and Roy disapproved very much of the election of Wiessner as one of our Honorary Members, a cause in which Jim McCarthy, Andy Kauffman and I took vigorous parts. Nevertheless, Dr. Thorington, though now dead for more than twenty years, remains my mentor, and every time I turn over a literary stone and learn something he apparently did not know, it’s a red letter day for me, for Roy was the ultimate scholar of alpinism, and was asked in 1956 to prepare the centennial article for The Alpine Journal.

Roy was also a trifle crusty, a condition which our long-time benefactor, Henry Hall, charitably blamed on his shyness. In 1952 at the Annual Meeting in New York he was introduced to Graham Matthews and asked, “How long were you in at Fortress Lake last summer?”

“About two weeks, Doctor,” replied Graham.

“I was in there twice myself, some twenty-five years ago, but could only stay a few days each time.”

“It’s great country, Doctor; you should have stayed longer.”

“I’d have liked to, but it took our pack train ten days to get there from Lake Louise.”

“Well!” Matthews rejoined; “we used a float plane from Golden and landed right on the lake.”

“Damned tourists!” huffed Roy, turning on his heel.

Getting back to Judge Putnam—before his appointment to the bench, he was a distinguished admiralty lawyer and not so much a climber as a distance walker—though he had made the ascents of Fujiyama, Whitney and Shasta, as well as the Breithorn. In mid-January of 1912, when he was 61 years of age, he had been holding court in Brooklyn on a Friday afternoon and was due to open court in Riverhead at the eastmost part of Long Island on Monday morning—so he packed up his judicial robes and walked the 74 miles from one courtroom to the other, over the weekend. You’d probably be killed, if not jailed, for trying that now.

Our next president was Henry Greer Bryant ,a lawyer who had been President of the Geographical Society of Philadelphia, thus Angelo Heilprin’s boss, and who had climbed all over the world from the Jungfrau to Popocatepetl, and from the icy cliffs of Labrador to the lava-covered slopes of Mauna Loa. In 1915, at the mid-point of Bryant’s term, the Club became incorporated, an act made necessary so that we could legally receive the first installment of the immense personal library of Henry Fairbanks Montagnier, this Club’s greatest asset to this day—but which has received a number of notable additions over the years, through the generosity of Roy Thorington, Horst von Hennig, Henry Hall, John Boyle, Armando Menocal, and most recently from Nick Clinch.

But then came the Great War (as our British friends still call it, for such it surely was to them) and everyone else was too busy, so, for the third time, we called on Professor Fay head the Club. During Dr. Fay’s final reign, Captain Albert Henry MacCarthy of the United States Navy, entered the management team and, 30 years later—long after his brilliant career in North American mountaineering—we elected him to Honorary Membership.

In 1920, Professor Fay returned to the teaching of modern languages at Tufts and we elected another lawyer, the second such from New York, Lewis Livingston Delafield—gotta watch out for those lawyers—they keep showing up in our management.

However, in 1923 we gave up—temporarily—on those devils, and elected the Reverend Harry Pierce Nichols rector of Holy Trinity Church, near Wall Street, a noted afficianado of New Hampshire’s White Mountains. ‘Uncle Harry’, as he was known thereabouts, celebrated his 85th birthday by making his 250th ascent on foot of Mount Washington; and it was under his aegis that the late Henry Hall came into the Club’s management. Henry soon served the longest sentence on record as the Club’s Secretary, and was primarily noted for his strenuous personal efforts to retain and enhance our membership. It was also in Henry’s library and livingroom that many great American mountaineering accomplishments were generated and planned.

Those New York meetings came to be held on the ground floor of the old firehouse at 113 East 90th Street that had been given to the Club in 1948 by another of our past presidents, Columbia University’s Dr. William Sargent Ladd. Up in the northwest corner of the ceiling one could make out a discontinuity in the metal tiles that showed where the traditional brass pole had once been, and which the New York City bureaucrats had required us to remove, as it was deemed a hazard for the premises’ new users.

During the annual meeting of 1957, as the various committee chairmen were giving their reports, it was soon to be the turn of the Chairman of our Safety Committee, the late Dr. Benjamin Greely Ferris, but he was not in the room. So a friend of his in the back ducked out of the meeting and called upstairs to the office: “Tell Ben he’s on next.”

Ben called backdown: “Tell John [Oberlin, another Californian, then president] that I’ve just gotten a raft of new data from the West Coast and it’ll take me most of an hour to merge it all in. Go on with the first program, and fit me in later.”

So, a note to that effect was passed it to the front of the meeting room.

Some 3/4 of an hour later, as the late Jack Graham was describing his scary traverse of the Matterhorn the previous summer, a long, rumbling crash reverberated through the wall separating the meeting room from the stairway. Jack froze in mid-sentence and Ben’s friend stepped out again to see the Chairman of our Safety Committee at the foot of the stairs, trying to regroup from the most serious fall of his long and distinguished climbing career.

Maybe those bureaucrats were on to something, after all.

In 1926, we elected another president (and lawyer) I never met—but whose footsteps I came to follow—almost literally—throughout the mountains of Western Canada, Howard Palmer whose major literary work remains one of the classics of North American adventure. Palmer went on, after his presidency, to edit the first number of The American Alpine Journal, an endeavor in which he was assisted, and then followed by Dr. Thorington.

* * *

Henry S. Pinkham, a dog, and almost-member of the Club. Click the photo to view other pics from this gallery.

I’m not going to bore you with a lengthy account of the almost election to membership of Henry S. Pinkham, a malamute with a distinguished climbing record, except to observe that despite the obstructionism of our then Secretary and later president, Bradley Baldwin Gilman, who finally got suspicious as he was writing up the Board minutes in the autumn of 1949 and held that application over for further consideration, there is nothing in our By-laws to this date, despite two major revisions, declaring such four-legged individuals ineligible for membership, and all you’ve got to do is listen closely to the cocktail hour conversation at any of our meetings and you’ll learn that a good many of our members apparently have canine ancestry.

Gilman was yet another lawyer, but he mostly did estate work for an insurance company, so we’ll forgive him, for his name rests—with that of his late cousin, the distinguished Princeton topologist, Hassler Whitney—on one of the early, and still finer, routes on what’s left of the great cliff on Cannon Mountain in New Hampshire.

However, because the UIAA has sent some spies to the meeting, in the form of our friend, Mike Mortimer, its first non-European president, and Paola Peila, the former Director of the Club Alpino Italiano, and her special escort, our friend Silvio Calvi, I must note that the AAC joined in the formal establishment of the UIAA in 1932, though when we woke up to how Eurocentric it was then, we dropped out, and only rejoined when Fritz sold us on the idea that the UIAA had come of recognize the center of the Earth was not Milan or Geneva, but really just north of here in the Grand Canyon.

Anyhow—after surviving the presidencies of Delafield (who disapproved of young Brad Washburn) Ladd, Palmer, then Henry Baldwin deVilliers-Schwab, a cotton broker whose 98-cent name came about from his marriage, and James Grafton Rogers, we finally elected presidents that I actually did know and work with, sometimes to their regret.

I would like, therefore, to take a moment to talk about my favorite Club president—other than some of those in attendance here tonight. Joel Ellis Fisher was our Treasurer for two lengthy periods—somewhat of a record, in between which he put in a stint as our President. I single out this major item in our history for two reasons:

1] I loved him; he helped us with that proxy fight—and we damned near won—for he knew more about how to pull off that sort of thing than the rest of us young Turks—Beckey, Matthews and Kauffman, and—I drew up his obituary for our Journal.

2] Ellis was an important business executive—mostly of the late Melville Shoe Corporation, and his generosity to alpinism and this Club was extraordinary. For years, he fundedresearch into glacial recession, all around the world—a condition which many present-day omniscient (and mostly Republican) politicians tend to dismiss as insignificant, if not irrelevant—and he managed the Club’s portfolio in a manner that was decidedly unique. A dabbler in Wall Street affairs, Ellis often invested some of our limited funds in speculative stocks, and, if they went up, the Club was the winner, but if they went down by year-end, he would make us whole out of his own pocket.

Speaking of the Club’s money reminds me of our dues. Back when we lived in New York, and Ellis was our Treasurer, it cost a nickel to ride the local subway—from one end to the other; and our dues were five dollars per year. Today the subway costs 30 times as much, and by that standard, our current dues are a terrific bargain.

However, I want to assure you once more that many of the greater accomplishments of this Club have been done by others than our elected leadership.

“Name a few names,” you might say: SURELY!

• H. (as in Henry) Bradford Washburn, Jr.—for whom the Club By-Laws were amended twice—by adding minimum age restrictions to keep him out, and he then became North America’s best known mountaineer.

• H. (as in Hubert) Adams Carterwhose tireless energy, over more than a quarter century, made our A A J the most inclusive and widely-read such journal in the world;

• Dee Molenaar, artist and cartographer, whose watercolors adorn many a mountaineer’s livingroom wall, along with those of another of our Honorary Members, Glendon Weber Boles;

• Dr. Ben Ferris, who developed this Club’s Safety Report into a ‘must read’ for climbers around the world—a work carried forward for the last 30 plus years by one of tonight’s honorees;

• Captain A. H. MacCarthy, who organized and led several major ascents, and who had the grace to turn down a gold medal proffered for the diligence of his work as leader of the 1927 expedition to climb Canada’s Mount Logan;

• Kenneth Atwood Henderson who wrote the original Handbook of American Mountaineering, which I helped to proof-read, and from which a great many people—including most members of the famed 10th Mountain Division—learned the game.

Yvon Chouinard, Francis Peloubet Farquhar, Royal Shannon Robbins, Friedrich Wilhelm Beckey, Raffi Bedayn, Dr. Charles Snead Houston, Fritz Wiessner, and another Honorary Member, the English geology Professor, Noel Ewart Odell ,who introduced ice-climbing to the Harvard Mountaineers and through them to North America—we have been blessed by the company of some of the world’s most notable mountain people, who advanced the techniques, the arts, the literature, the physiology and the manufacture of mountaineering materiel, and thus set an ever higher bar for those who aspire to follow as patrons of alpinism;

One of our foremost members was the late Miriam O’Brien Underhill, America’s first lady of alpinism, who deftly defined mountaineering as “a form of insanity,” and who also did not suffer fools gently. At one Annual Meeting, held in Boston, I was talking with Miriam and a group of her friends when a brash and pompous young climber came over and announced a wonderful litany of ascents he had made in the Dolomites, the previous summer—which included one route on the Torre Grande—the Via Nuvolau—which he proudly said was done “sans gide.”

Miriam, then in her seventies, looked him straight in the eye: “Young man, before you were born, I led that route, sans homme.”

For those who may have a small amount of wine left, I ask you nowto rise and offer a toast to the honor and memory of those who have brought us this far.

* * *

Walter Bonatti, Honorary Member of the American Alpine Club. Click the photo to see more from this gallery.

Now for a few additional introductions, it is my privilege and duty to present to you the latest persons the Directors of The American Alpine Club have elected to Honorary Membership, thus telling the world that we wish more people would go out and do likewise. Two of them could not be with us this evening, but in alphabetical order, as well as perhaps in seniority if not merit, I am privileged to present to you:

[1] Walter Bonatti, somewhat younger than me and a native of Bergamo, made numerous spectacular climbs in the Alps, including a winter solo climb of the north face of Il Cervino, and new routes on the Aiguille du Dru and Grand Capuchin as well as his famous climbs in Patagonia; but his great and most heroic work was high on K2, in setting things up for others to finally make that summit.

[2] A contemporary of Walter’s, Joe Brown is known as one of England’s “hard men,” who made many spectacular post-war ascents in the British Isles, some of his best with our friend, Ian McNaught/Davis, being on the sea cliffs and stacks of the British Isles, as well as further afield in the Atlas Mountains and on the Mustagh Tower. But he is probably best known for his first ascent of Kangchenjunga (all but the last meter) with George Band. We have a message from Joe…

——————

[3] Tom Frost, the principal savior of Camp 4 and a Yosemite pioneer beyond our praise, was at his greatest in the ascent of the south face of Annapurna. A mountaineering visionary of the first order, Tom was in the forefront of probing the Ruth Gorge area of Alaska and in a great many other good and laudable events for the benefit of American mountaineering.

[4] In vocation and avocation, Dr. Louis French Reichardthas gone about the adventure of life in style. It’s hard to top a mountaineering curriculum vitae that includes Nanda Devi, K2, and Everest’s Kangshung Face, plus the presidency of this club. His professional life is no less distinguished as a top-end cell physiologist at U.C. San Francisco, pioneering new routes in developmental neurobiology. Happy Birthday, Lou!

[5] As a literary researcher and author of numerous authoritative accounts, Audrey Mary Salkeld has contributed more to the accuracy of the historical record than anyone since the Reverend Coolidge and our Dr. Thorington. Her presence on our list of Honorary Members is a continuing sign that this Club’s interests transcend more than physical success, and shows we have a strong, ongoing commitment to the intellectual record as well.

(6) The grandson of Arthur Oliver Wheeler (1860 -1945), surveyor of the B.C.- Alberta boundary through the Canadian Rockies and founder of the Alpine Club of Canada; and son of Edward Oliver Wheeler (1890-1962), the first surveyor of Mount Everest and later Surveyor-General of India nearly 100 years after Sir George Everest; Dr John Oliver Wheeler, now retired from the Geological Survey of Canada, was their Chief Scientist for seven years, but spent much of his career charting the mountains of Western Canada. His work was of great interest to many, including myself, for I came across him on several occasions in the Selkirks while he was mapping the bedrock and I was working on the guidebook.

[7] John Edward Williamson, a sometime official of Outward Bound, is a mountaineer of international distinction, who guided us through the trek from New York to Golden, and who continually makes me proud that I brought him into this game. For uncounted years, ever since my valued associate in alpinism, the late Ben Ferris, laid it off on him, Jed has been Editor of the Annual Report of this Club’s Safety Committee; a service of incalculable value to climbers, young and old, across North America and around the world. Happy Birthday to you, too, Jed!

And now, it is my unusual pleasure to announce the election, though a few years too late, of one additional honorary member, who also cannot be with us tonight, for he died two dozen years ago—[8] the late Arnold Wexler whose labors at Carderock, near our nation’s capital, in conjunction with those of another late honorary member Richard Manning Leonard in Yosemite, led to the greatest mountaineering treatise, perhaps of all time—the ongoing value of which it is impossible to overstate: BELAYING THE LEADER.

* * *

Finally—having arranged with the wine steward to offer every table a special sample from the private cellars of my great-uncle, Percival Lowell who died in office, nearly a century ago, while serving as President of the oldest mountaineering organization in the Americas—I ask that we all rise again, in a toast and salute to these eight highly deserving members of our craft.

* * *

President Swenson, I hope I have served you well; and now I can—as Mrs. Putnam and I used to say in television broadcasting—fade to black. Perhaps, however, you’d like to allow Ms. Salkeld to say a few words in collective rebuttal.

* * *

In any subsequent publication of these remarks, I wish them dedicated to those kind and tolerant friends who brought me up in alpinism: Maynard Malcolm Miller, William Robertson Latady (1918-1979); Benjamin Greely Ferris, Jr (1919-1996); Andrew John Kauffman, II (1920-2002); and Dee Molenaar—all of whom have also played significant roles in The American Alpine Club.

—William Lowell Putnam

The Prescription—February 2021

STRANDED – STUCK RAPPEL ROPES

CASTLETON TOWER, UTAH

Highline anchor bolts atop the northwest corner of Castleton Tower, Utah.

Just after sunset on December 4, two male climbers (ages 32 and 36) called 911 to report they were stranded halfway down 400-foot Castleton Tower because their rappel ropes had become stuck. Starting near sunrise, the pair had climbed the classic Kor-Ingalls Route (5.9) on the tower’s south side. They topped out later than expected, with about an hour and a half of daylight left.

Armed with guidebook photos and online beta, they planned to descend via the standard North Face rappels. The two saw a beefy new anchor on top of the northwest corner of the tower and decided this must be the first rappel anchor. Tying two 70-meter ropes together, the first rappeller descended about 200 feet and spotted a bolted anchor 25 feet to his right, with no other suitable anchor before the ends of the ropes. No longer in voice contact with his partner, he ascended a short distance and moved right to reach the bolted anchor. It appeared that one more double-rope rappel would get them to the ground. Once both climbers reached the mid-face anchor, they attempted to pull the ropes. Despite applying full body weight to the pull line, they could not get the ropes to budge.

Contemplating ascending the stuck rope, the climbers realized the other strand had swung out of reach across a blank face. The climbers agreed that recovering the other strand was not safe or practical, nor was climbing the unknown chimney above them in the dark. The climbers were aware the temperature was expected to drop to 15°F overnight, so they made the call for a rescue. They were prepared with a headlamp, warm jackets, hand warmers, and an emergency bivy sack.

A team of three rescuers from Grand County Search and Rescue was transported to the summit via helicopter. One rescuer rappelled to the subjects around 9 p.m. and assisted them in rappelling to the base of the tower.

ANALYSIS

The rescuers discovered the climbers had mistakenly rappelled from an anchor used to rig a 500-meter highline (slackline) over to the neighboring Rectory formation. Instead of rappelling the North Face, as planned, the climbers had ended up on the less-traveled West Face Route (5.11). Because the highline anchors were not intended for rappelling, friction made it impossible for the climbers to pull their ropes.