FALL FROM ANCHOR | TETHER CLIPPED INCORRECTLY

Arizona, Cochise Stronghold, Owl Rock

On the afternoon of January 31, 2021, Tim Parker (35) suffered a ground fall from the anchor above Naked Prey (5.12a) in Cochise Stronghold. Parker is a climber with over 15 years of experience. His partner, Darcy Mullen (32), is a climber of over 10 years. They are both mountaineering instructors for an international outdoor education organization.

The pair had decided to finish their day with several pitches on Owl Rock, a pinnacle with several high-quality one-pitch routes. Mullen led Nightstalker (5.9), a classic mixed gear/bolt route on the lower-angle front side of Owl Rock. She built an anchor and belayed Parker to the top.

Mullen rappelled the overhanging backside of the pinnacle, passing over the line of Naked Prey. Parker then rigged the two-bolt anchor with a quad cordelette in order to top-rope Naked Prey, and Mullen lowered him to the base of the climb. He then top-roped the route. Back on top, Parker decided it made more sense to rappel than be lowered due to the location of the anchor bolts.

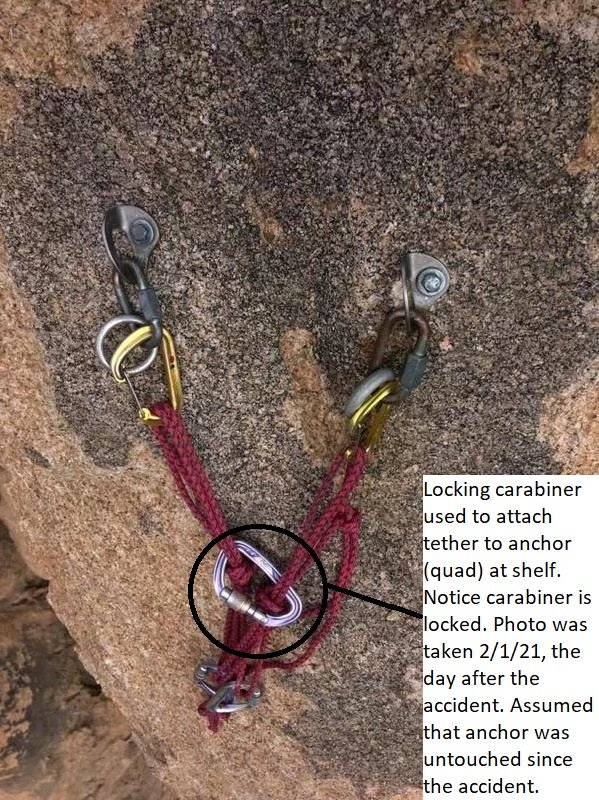

Quad cordelette rigged at the rappel anchor on Owl Rock, as found the day after the accident. The carabiner on the shelf of the cordelette is still in place and locked.

For an anchor tether, he used a double-length sewn nylon runner girth-hitched around both hard points on his harness. Parker had pre-rigged the tether with two overhand knots, dividing the sling into three segments, to allow for various clip-in points and for extending his rappel device. He used a locking carabiner to clip the tether into the shelf of the cordelette anchor. Unbeknownst to him, the carabiner was not properly clipped to his tether, but this fact would not be revealed for several minutes. Parker did a visual double-check of his connection, asked for slack, and weighted the new system. With nearly full body weight on the tether and the carabiner locked, he told Mullen to take him off belay. After doing so, she walked around the formation to Nightstalker’s base, where she began packing their gear.

Meanwhile, Parker untied from the rope and threaded it through the rappel anchors, then pulled the rope through the rings until both ends were on the ground. Approximately five minutes after taking her partner off belay, Mullen heard a yell and watched Parker fall from the top of the climb. He free-fell approximately 60 feet, then fell another 30 feet down lower-angled rock (70–80°) before hitting the ground.

Mullen found him lying on his back. His head was approximately one foot away from a small boulder. A trained Wilderness First Responder, Mullen stabilized Parker until a nearby climbing party arrived to help. The other climbers dialed 911. The time was 5 p.m. Mullen then directed the other climbers to help take vital signs and stabilize Parker until paramedics arrived at about 5:30 p.m. He was airlifted to Banner University Medical Center in Tucson.

Parker spent about three and a half weeks in the hospital and rehab center, with many broken bones, extensive abrasions, a mild traumatic brain injury, a nearly severed left ear, and nerve damage. After being discharged, Parker spent about two and a half months in a wheelchair and another month on crutches. Though still recovering, he was able to return to working on expedition and climbing courses in November 2021.

ANALYSIS

Reconstruction of the Owl Rock anchor showing how an overhand knot in the tether sling likely jammed on the locking carabiner and held the climber’s weight temporarily. From the climber’s perspective, the sling appeared to be properly clipped.

Due to some memory loss from the accident, the precise cause of the fall—and the five to ten minutes leading up to it—can only be hypothesized. Parker believes he initially clipped the end of his tether into the cordelette but that this connection was too long to give him easy access to the anchor. He must have tried to shorten his tether by clipping the second knotted loop of the sling.

After the accident, his locking carabiner remained clipped to the cordelette and locked shut. The tether was not compromised in any way. Parker assumes that when he tried to clip in, he pushed the knot through the opening of the locking carabiner but did not clip the actual loop of webbing. When he weighted the system, it is believed the knot jammed against the edge of the carabiner just enough to hold his weight. Parker’s rappel device was still clipped to a gear loop on his harness after the fall. Likely the knot in the tether popped through the carabiner when his body weight shifted as he reached for the device.

Parker and Mullen recreated this scenario at home. They noted that while it was difficult to fully weight a knot placed in the carabiner this way, when it was set in a particular spot the knot could hold weight (especially when lodged in a smaller D-shaped locking carabiner). Once loaded, the jammed knot appeared similar to a properly clipped and loaded tether.

Many aspects of this accident line up with themes in other descending accidents. Since this was the last climb of the day, they felt pressure to depart for the two-hour drive back to Tucson. The couple were also about to start a three-week outdoor education course. Such transitions can be stressful and distracting. Parker reflected that the accident’s primary cause was complacency, as he ultimately failed to catch his own mistake.

Other aspects are important as well. Parker had used his tether system many times, but more often for rappelling multi-pitch climbs. Using a new system—or an old system in a new context—raises a yellow flag that should be recognized. Perhaps the better option would have been to rig the system he used more commonly for cleaning bolted anchors on sport climbs. The only reason he used the system in question was because it was already rigged from his previous climb on Nightstalker.

Lastly, Parker was not wearing a helmet. This was a conscious decision. Before this accident, he regularly wore a helmet while leading and/or when concerned about overhead hazards. But since Naked Prey is a short, steep pitch on small pinnacle of rock, rockfall was not an issue. As he was top-roping, there was little to no chance of hitting his head in a fall. Of all of the miracles herein, the greatest might be his avoidance of serious brain damage and/or death. Parker now wears his helmet in all outdoor roped climbing contexts. (Sources: Tim Parker and Darcy Mullen.)

EDITOR’S NOTES

Redundancy: Whether you clip an anchor with the rope, quickdraws, slings, or a commercial PAS, it usually takes little effort or extra gear to create a redundant connection. It’s true that climbers rely on equipment with zero redundancy all the time, including the belay loop on your harness or the rope while you’re climbing, lowering, or rappelling. But there’s seldom a good reason not to double up at an anchor.

Check It! Accidents and near misses with inadequate anchor connections occasionally involve outside forces (rockfall, for example). But most of the time they can be prevented by double- and triple-checking your connection.

Take it from Dougald MacDonald, past editor of ANAC: “One of my scariest moments in four-plus decades of climbing came during a long series of rappels with two partners in the French Alps. Midway through the descent, with all three of us perched on a sloping ice-covered ledge, one of the climbers hissed at me, “Do you know you’re not attached to anything?” In our rush to get down, I had unclipped from the ropes on the previous rappel without ever clipping the anchor. Fortunately, neither a nudge from my partners, a slip on my crampons, nor a gust of wind pushed me off the tiny ledge.”

Personal tether tied with a water knot that came undone at a rappel anchor on the Grand Teton in 2016, causing a tragic accident. NPS Photo

From the Archives: Here are two incidents from past ANACs indicating ways climbers can be disconnected from anchors. Tragically, both of these ended with fatal injuries.

PAS Disconnected on Half Dome’s Snake Dike (ANAC 2016)

Knotted Sling Comes Undone on Grand Teton (ANAC 2017)

In all of the cases discussed here, a closer look at the anchor connection might have prevented a disastrous accident.

THE SHARP END: AN UNPLANNED BIVY

In Episode 73 of the Sharp End Podcast, Ashley and Christian Kiefer discuss a cold, uncomfortable, and unexpected night out at 13,000 feet on Mt. Emerson in California’s Sierra Nevada.

The monthly Prescription newsletter is supported by the members of the American Alpine Club. Questions? Suggestions? Write to us at [email protected].