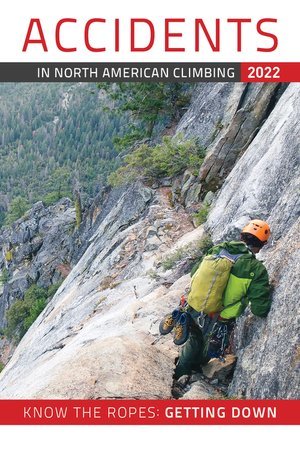

Know when to call for a rescue (and have the ability to communicate). It’s tough to know when the right time is. Ultimately, Kate decided they should call for help when she felt like she could not safely use her hands. The need for a rescue became more apparent when they were rappelling back down to Big Sandy after attempting the Zig-Zags. The ropes were extremely icy, making the rappel dangerous. They rappelled with Grigris and used slings as “third-hand” backup prusiks, and did not feel it was safe to try and retreat further. There were legitimate concerns that if they attempted to continue upward, Kate and/or Nick could have gotten injured; this would have made the situation much worse and the rescue more complex.

They only carried one cell phone with them, and fortunately they were able to make a phone call to 911. To communicate with YOSAR, they kept the phone off when not in use and kept the phone next to their bodies to keep it warm and preserve the battery. (Source: Yosemite National Park Climbing Rangers.)

This report is adapted from a story at Yosemite Climbing Information, published by Yosemite rangers.

SEASONAL HAZARDS: THE EDITOR’S STORY

The shoulder-season months of March/April and October/November can be perilous in Yosemite. After a long winter spent indoors, clear and sunny weather in early spring can lure climbers onto the walls. In fall, peak fitness honed over summer, combined with seemingly endless weeks of perfect weather, can tempt climbers to squeeze in one last end-of-the-season send.

As the old saying goes, “Good judgment comes from bad experience.” Take it from Pete Takeda, editor of ANAC:

“I spent seven years living in Yosemite. Over that period, I climbed many big walls and suffered more than a few bad-weather epics. One instance stands out.

“I was coming off a long winter and was itching to get on a wall. So in early April, my partner and I launched up an El Cap route called Lost World, foolishly ignoring a storm forecast. There was no internet back then, but the San Francisco Chronicle, delivered to the Valley on a daily basis, had a generally solid forecast printed in plain black and white on the front page. After two days of climbing, a storm clobbered us above the point of no return, and we spent the next three days soaked to the bone. My shelter was a thin sleeping bag and a leaky bivy sack. On day one of the storm, we foolishly declined an NPS rescue.

On day two I became concerned about hypothermia and asked my partner, ‘Are we going to make it?’ He was a veteran survivor of epics on walls and big mountains. His reply was frightening. ‘How the f*** should I know?’

“Day three dawned with sleet, but by noon the sun had peeked out. We jumped into action, climbing for our lives, and barely summited during a few hours of good weather. I’d lost ten pounds and acquired a case of trench foot. Had we had another day of bad weather I might not be sharing this tale.”