Photo by AAC Member Chris Vultaggio

Since 2006, the Mohonk Preserve, New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation, the Palisades Interstate Park Commission, and the American Alpine Club partnered together to create a campground near the popular Shawangunks climbing area. Construction was completed in 2014 by The Palisades Interstate Park Commission, and now The American Alpine Club and The Mohonk Preserve operate and manage 50 brand-new campsites, all within a stone's throw of miles of world-class rock. This is a watershed moment for one of the most popular rock-climbing areas in the country. For the first time since climbing in the “Gunks” began over 80 years ago, hot showers and running water are available for climbers who want to camp within view of the cliffs.

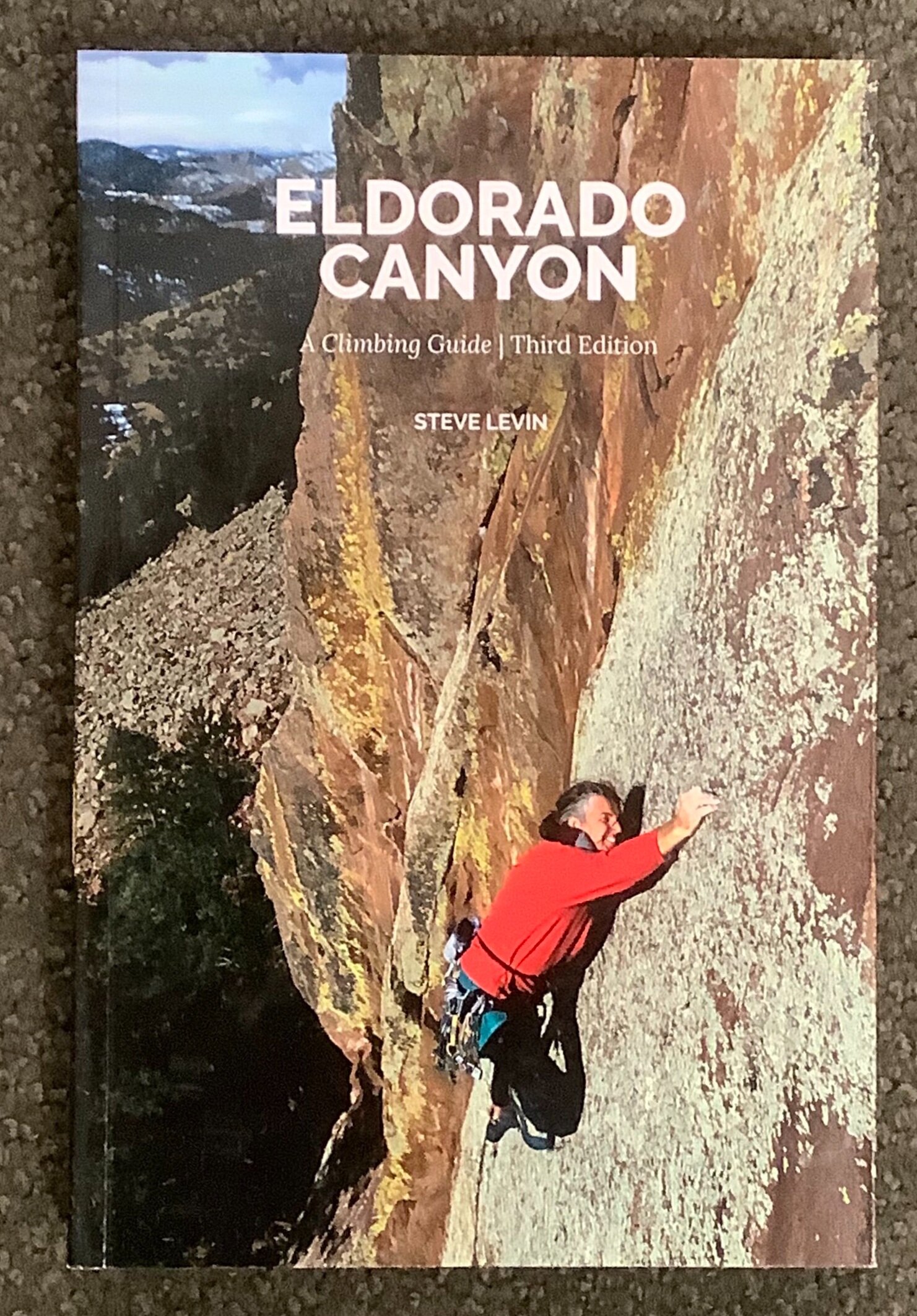

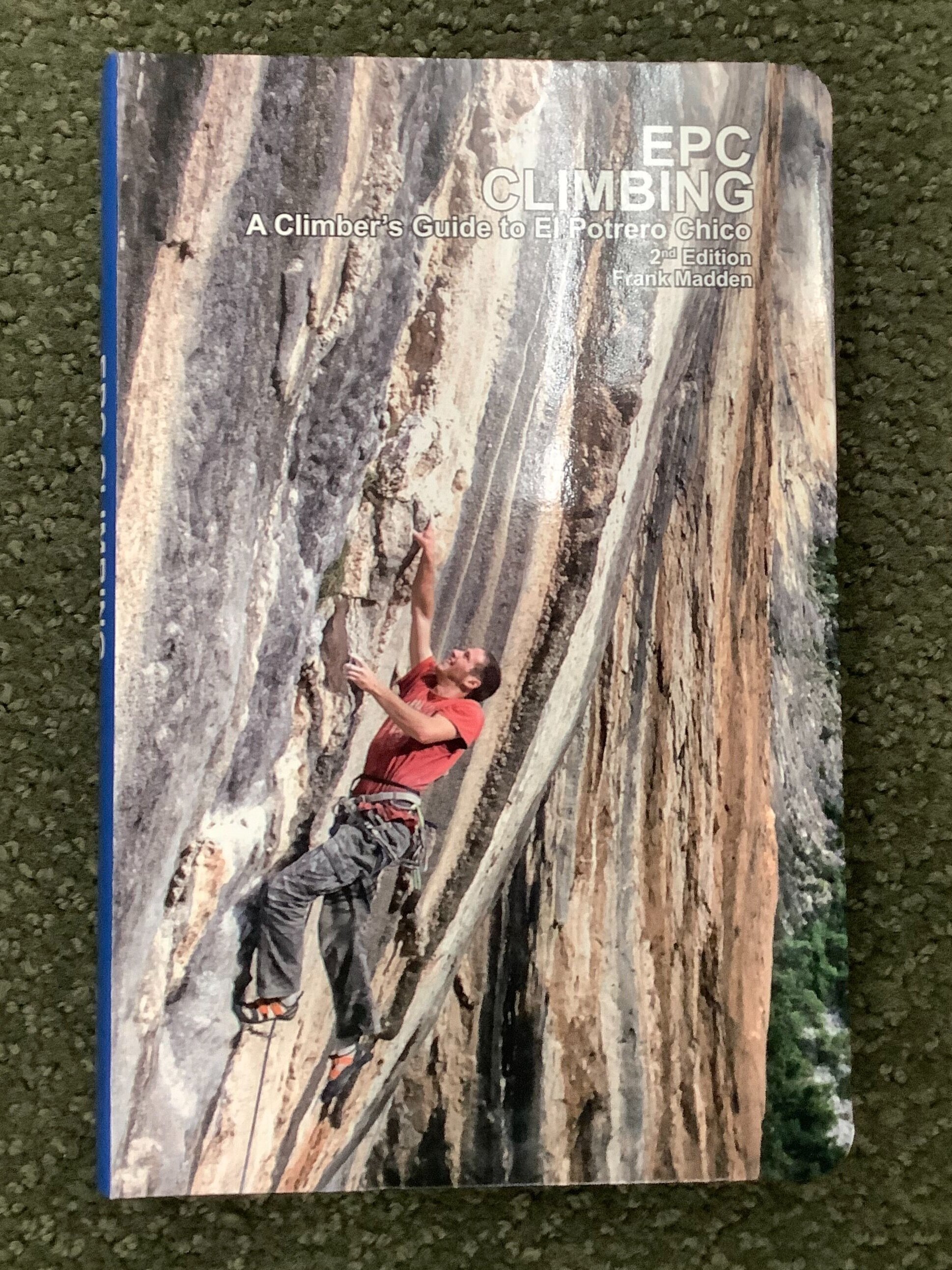

Just 90 miles north of New York City, the Gunks offers about 1,200 routes up to 5.14 on immaculate quartzite, with spectacular views of the Hudson Valley below. As you walk the historic carriage roads that access the cliffs, you feel part of the climbing history that dates back to 1935. The Gunks climbing history starts with Fritz Wiessner, a European immigrant with extensive mountaineering experience. He noticed the cliff from across the Hudson River and returned the next week to document the first technical climb, “Old Route” (5.5) on Millbrook. Hans Kraus was the second immigrant with mountaineering experience to arrive on the scene. Together the duo would lay the groundwork for traditional climbing in the Gunks, cementing their legendary status by pairing up for FA’s of world class routes such as “Horseman” (5.5) and “High Exposure” (5.6). Women played a steady hand in climbing and exploring, most notable from this time period was Bonnie Prudden with over 30 FA’s to her credit, including the mouth-watering “Bonnie’s Roof” (5.9).

During the late 40s and early 50s climbers continued exploring the wealth of potential in the Gunks. William Shockley, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist (for his invention of the transistor), added the ever-popular “Shockley’s Ceiling” (5.6). Jim McCarthy, future president of the AAC, became the leading force for this era, contributing undisputed classics like “MF” (5.9) and “Birdland” (5.8).

Up to this point, most climbers at the Gunks were associated with the Appalachian Mountain Club (AMC). The AMC were considered stodgy and uptight, and they wanted control over the cliff as regulators of who would and would not climb. This gave rise to a resistant group of climbers, who referred to themselves as the Vulgarians and were often fueled by drugs, alcohol and loud music. They refused to follow the rules or recognize the AMC’s authority. After several spats and disagreements, the Smiley Family (who owned the majority of the cliffs, granted the Vulgarians permission to climb and the presumed AMC dominance ended.

Standards continued to rise with the onset of the ‘60s. Phil Jacobus climbed “Jacob’s Ladder” in 1961 to produce the Gunks’ first 5.10. Even to this day, it sees very few ascents due to the bold “X” rating. Yvon Chouinard and several other West Coast climbers arrived with several new hand-forged chromoly pitons, which turned out to be a game changer. Chouinard freed the first pitch of “Matinee” (5.10d) and aided through the second. The only person who could follow the pitch at this time was Dick Williams. William’s gymnastic background and dynamic style fit well with the sometimes-blank nature of the rock. He climbed the first, albeit short, 5.11called “Tweedle Dum”. In 1967, John Stannard sent the 8 foot aid ceiling known as “Foops” (5.11c) in a marathon 5-day siege. This style represented a shift; climbers began realizing that persistence and conditioning were needed to push standards forward. As such, many weekend warriors began training mid-week in order to be in top shape.

With the ‘70s came the Clean Climbing Era. Over the next several years, pitons fell out of fashion as it was becoming clear that they were leaving severe scars in the rock. John Stannard was a huge proponent of the idea of “clean climbing”, and in addition to only using clean gear, worked hard to make “clean and free” ascents of aid routes. Though Stannard was the biggest pusher of this new style, he wasn’t alone as climbers such as Marc Robinson, Kevin Bein, Steve Wunsch and John Bragg (like McCarthy, another future AAC employee) joined in the growing fray. Classics like “Gravity’s Rainbow”, “Kansas City” and “Happiness is a 110 Degree Wall” (all 5.12c) represent some of the best and hardest lines from this era. Another influential climber to come out of this time period, and one who adhered to a strict code of preservationist ethics, was the indefatigable Rich Romano. Over the next several decades, Romano would establish hundreds of climbs, and develop 90% of the entire cliff of Millbrook.

The ‘80s brought a continuation of Stannard’s ideas of free-climbing, as aid climbing had become obsolete. More and more climbers joined the scene, the most prolific being Russ Raffa, Russ Clune, Jack Mileski, Jeff Gruenberg, Hugh Herr, Mike Freeman, Jim Damon, and Felix Modugno. This collective, though not always acting cooperatively, added enough classic and scary routes to keep any climber busy for years. Lynn Hill, widely considered to be one of the best climbers of the time (male or female) moved to the Gunks in 1983. She joined the guys on many new routes such as “Vandals” (the Gunks’ first 5.13), and onsighted the FA of “Yellow Crack Direct” (5.12c R/X). Later on, another world class talent would storm the scene in the form of powerhouse Scott Franklin. He pushed Gunks standards to 5.14 with his ascent of “Planet Clair”, though he is better known for establishing the modern testpieces “Survival of the Fittest” (5.13a) and “Cybernetic Wall” (5.13d). To this day, the magnitude of bold and hard climbing that was done during this time is yet to be fully appreciated.

The inevitable decline in fast-paced development began in the ‘90s. Many key players from the days of yore had moved on or quit climbing, and much of the quality available lines had already been seized. However, some locals quested on, like Jordan Mills. He added many hard topropes like “Bladerunner” (5.13d) to the area, and these testpieces became the groundwork for what would become the bouldering revival of the late ‘90s. His climbs involved around nails-hard moves on barely-there holds, bridging the gap between bouldering and routes. As more and more climbers realized new route potential had mostly been covered in the ‘80s, enterprising locals turned to the next logical place for new climbs: the wealth of boulders at the base of the cliffs. With the invention of the crash pad, once-dangerous boulder problems were easily protected, and bouldering development exploded. Bouldering in the Gunks, long considered a sideshow to the main attraction of routes, firmly established itself as a legit pursuit.

While it was long thought that the Gunks was all but climbed out, the last few years have shown otherwise. Thanks in part to modern gear, and stylistic choices like rappel inspection and toprope rehearsal, a new resurgence in the Gunks is taking place. In 2010, Cody Sims got the ball rolling when he completed his multi-year project to create “Ozone” (5.14a). This world-class route takes an incredible line up gorgeous rock, and is arguably the best route in the entire Gunks. Brian Kim applied modern bouldering skills to a steep prow to create “Monumantle” (5.13d R). Other climbers such as Whitney Boland, Andy Salo, Ken Murphy, Dustin Portzline and Christian Fracchia unearthed some modern gems and resurrected old forgotten classics. Lately, it’s not unusual to see a strong group of climbers brushing cobwebs off old testpieces, or swinging around inspecting for new lines.

And now, thanks to the American Alpine Club and Mohonk Preserve, all this climbing and history can be just a short walk from your campsite. Each site has nicely padded camping beds, big enough for two small tents. We offer showers and sinks for cleaning your dishes, flushable toilets and handicap-friendly facilities. The well-constructed buildings are modern and the entire campground blends into the surroundings, keeping a quiet low-profile. Come for the weekend but don’t be surprised if you stay for the season. The Gunks’ magic permeates anyone fortunate enough to spend a perfect afternoon high above the trees, cutting feet as they pull over another classic overhang.