In this installment of our Grassroots series, we share the story of two AAC members pushing their personal limits. If you're an AAC member and want to see your climbing story featured, send an email with a brief description to [email protected] for a chance to share your story!

Camden Lyon walking along a large crevasse on Nevado Pisco. PC: AAC Member Torsten Lyon.

Grassroots: Unearthing the Future of Climbing

By: Sierra McGivney

Camden and Torsten Lyon were cold, so cold that cold didn’t feel cold anymore. Their fingers were frozen and ice covered their face as the sun rose. In the Peruvian morning, the two stood at camp having returned from attempting to summit Huascaran (22,205 ft) the highest mountain in Peru.

“You could see the shadow of the curve of the earth projected into the stratosphere. I think we were both too miserable to enjoy it,” said Camden as he laughed.

13-year-old Camden on Capitol Peak’s iconic knife edge. PC: AAC Member Torsten Lyon.

The first thing that you should know about Torsten and Camden is that Torsten is Camden's father. Camden has been backpacking and bagging fourteeners for as long as he can remember. At the age of four Torsten began involving Camden in the planning process. He showed Camden where they were on the map and where they needed to go. Even though Camden doesn’t remember those trips well, something stuck.

“Growing up in Colorado, the mountains are as much a part of me as my hand or foot. Nowhere, not even in my own living room, am I more at home than the side of a cliff, a windswept summit, or a towering glacier,” said Camden.

13-year-old Camden ascending the Peakrly Gates on Mt. Hood. PC: AAC Member Torsten Lyon.

So it was not all too surprising when an 11-year-old Camden approached Torsten about a trip to the Cordillera Blanca. He put together a list of skills he had and skills he needed, and a multi-year plan to acquire the skills needed to climb peaks in the Cordillera Blanca. Torsten said yes—and the two set out on a multi-year plan. They climbed Mount Hood, multiple snow climbs in the North Cascades and Colorado (Grizzly couloir), the Exum Ridge on Grand Teton, and the Kautz Glacier on Mount Rainer. COVID-19 slowed them down but also allowed them time to acquire more skills and experience. The two were set to head to Peru in the summer of 2022 until Torsten fell skiing and tore his meniscus.

That didn’t stop them. They had set a goal and were willing to work around the obstacles in their way. Torsten had knee surgery and three weeks later he was back training for their trip and hiked Square Top Mountain all with the approval of his doctor. They decided to push their trip back a couple of weeks and acclimatize in Colorado.

PERU

One flight from Denver to Lima, Peru, and a nine-hour bus ride later, Camden and Torsten arrived at their hotel in the town of Huaraz. Donned in pounds of gear and giddy nervous excitement, the two awaited their guide, Edgar. They had been communicating with each other via email and google translate.

Nevado Chopicalqui and the peaks of Nevado Huacaran tower above the Refugio Pisco. PC: AAC Member Torsten Lyon.

“So he does show up, which we didn’t know if he would,” said Torsten.

Edgar suggested that they try to climb Pisco (18,871ft) since it’s a relatively easy mountain and the dry season started late that year. Torsten and Camden planned to climb Pisco without Edgar and meet back up with him the following Wednesday on a certain switchback. By 5 am on Monday, the two were off to start their grand Cordillera Blanca adventure.

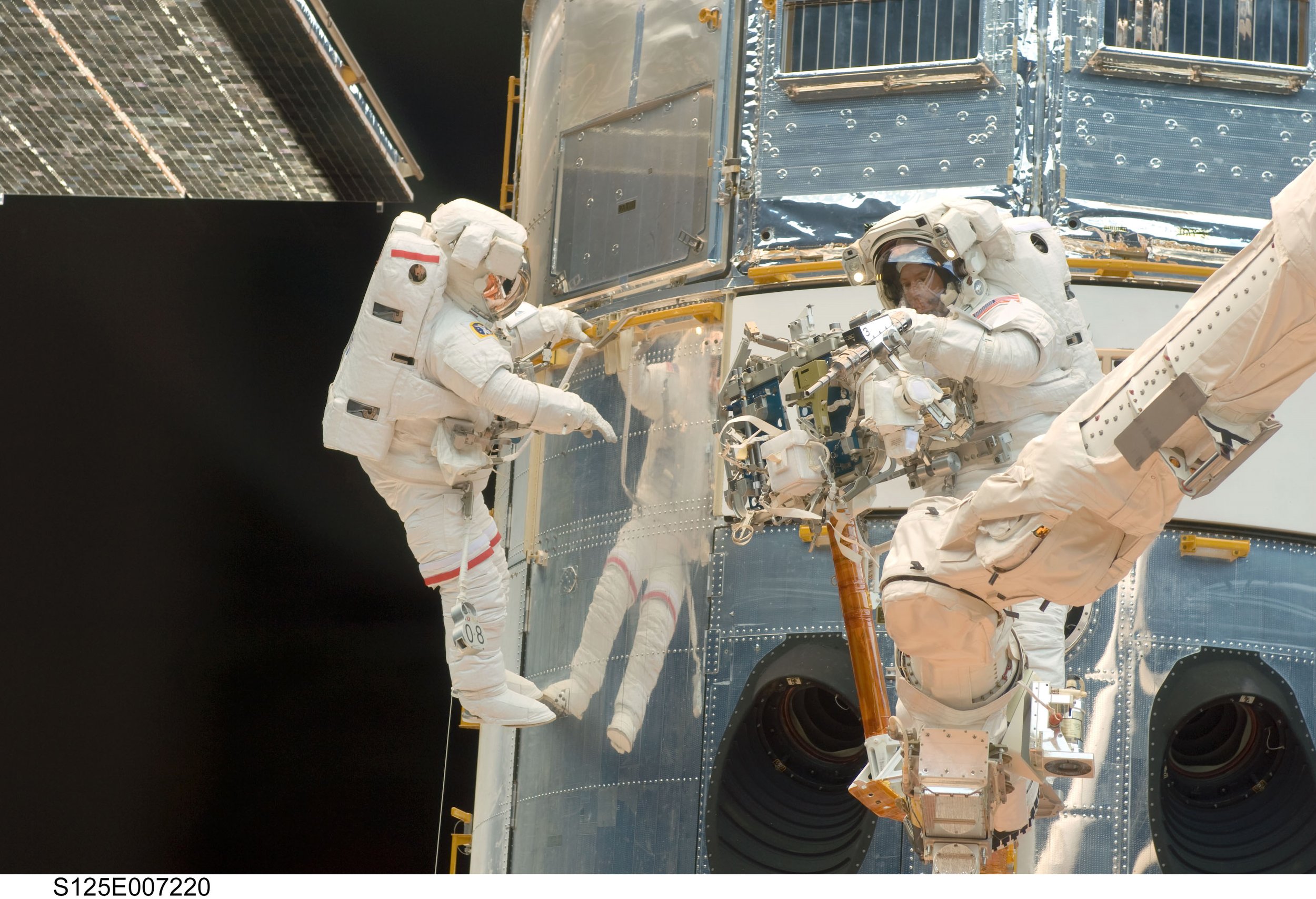

Pisco set the precedent for how climbing in Peru would go. Based on guidebooks written 20 or 30 years ago, Pisco was supposed to be 45 degrees or less with minimal crevasse danger. When Torsten and Camden set crampons on the snow Monday morning they found 50-degree angle snow climbing and big crevasses. The glacier along the ridge was fractured off both sides. The silence and wind whipped past them as they soloed up the mountain. Sixty feet below the summit they stopped and turned around. They just didn’t have the right gear for the unexpected conditions.

Descending from the summit ridge of Nevado Yanapaccha with Nevado Chacraraju in the distance. PC: AAC Member Torsten Lyon.

“For the third day [there]... on a mountain 5,000 feet higher than I’ve ever been, I was alright with it,” says Camden.

At a junction in the road, Torsten and Camden met with Edgar that Wednesday. As they traveled to the other side of the valley to climb Yanapaccha they conducted a dual interview. Both parties seemed happy with the outcome. Edgar was stoked that the two were competent climbers.

Yanapaccha, their next objective, has a standard route and a harder route. Unfortunately, the glacier on the mountain has receded significantly in the last 20 or 30 years and left giant seracs above the standard route. Edgar suggested they veer away from the cornice and climb the harder line. Three pitches of hard alpine climbing later, they stood on the summit.

Back in town, Edgar informed them that someone had successfully climbed Huascaran that year. The thing about Huascaran is that it’s a relatively easy mountain with a lot of high objective danger.

“It’s a roll of the dice,” said Torsten.

Nevado Chopicalqui (20,847), Huascaran Sur (22,205), and Huascaran Norte (21,865) in the morning alpenglow, taken from the west face of Nevado Yanapaccha (17,913).

Avalanches and serac falls are common. So, over a meal, Torsten and Camden discussed the climb. They researched and read about past events and the frequency of avalanches and ice falls during that time of the season. The two generally prefer harder terrain with less objective hazard. This was the opposite.

“I know for me, being a climber, and also a parent, I wanted to just take a little time to like, [discuss] do you want to do this or not?” said Torsten.

They decided to go for it. At base camp, they waited in the cold for Edgar to get ready. Unfortunately with the language barrier, they had gotten ready and taken down camp before Edgar woke up. They watched as two climbers from Boulder, Colorado, passed them.

Crossing through the dangerous terrain below active seracs. PC: AAC Member Torsten Lyon.

Toes frozen in their boots they began the long walk upwards. As they climbed through the snow-filled basin after the first pitch of climbing, avalanche debris came into view. The two climbers from Boulder had been swept 300 feet on the second pitch and rode the avalanche until they stopped right before the pour-over.

“I had no idea what was happening. I thought I was going to die. It wasn’t funny,” said one of the Boulder climbers to the trio.

Suddenly the air was eery. Below the summit, Torsten started to develop altitude sickness and the team decided to turn around. They slept a couple of hours and then descended back down to 15,000 feet past camp one. Neither Torsten nor Camden was upset about not summiting.

“We were really happy to be safely off the mountain and I think we both cared a lot less about having missed the summit,” said Camden.

They passed a group of climbers from Poland headed up Hauscran as they made their way back down to Huaraz. Between camps one and two, serac falls hit the climbers from Poland. luckily they all lived.

ISHINCA VALLEY

In nine days' time, Torsten and Camden planned to climb four big mountains: Nevado Ishinca (18,143ft), Urus (17,792ft), Ranrapalca (20,217ft), and Tocllaraju (19,797ft). At this point, Torsten and Camden were confident that they could climb certain mountains and get to high camps without Edgar.

Camden belaying one of the final pitches on Nevado Ranrapalca. PC: AAC Member Torsten Lyon.

“It’s more like our guide was a paid climbing partner that carried the extra rope and climbed all of the hard pitches,” said Camden.

The two climbed Urus and Nevado Ishinca with no problem. Ranrapalca proved to be a “wicked hard mountain.”

Five pitches of AI3 and M3 climbing in the dark and two pitches watching the sunrise led to a lovely summit. It proved to be a challenge as the two had little to no experience in mixed or technical ice climbing and the climbing was steep.

“If you look at a constant angle up, you can't see the stars because it gets so steep. It was just really intimidating,” said Camden.

Once down from the summit Camden and Torsten checked their Inreach to find that bad weather was approaching. They stashed gear and took a rest day and then it became a mad dash to climb Tocllaraju before bad weather moved in.

Taken on the descent from their hardest summit, Nevado Ranrapalca.

They climbed the standard route which ends 400 feet below the summit. A giant snow mushroom formed by the wind blocks the route to the summit. Camden asked his dad to put him on belay and traversed out to see if there was a route around. He saw a clear path but it was late in the afternoon and they were the only ones on the mountain. Torsten belayed him back in and they descended.

“There were some great decisions in not going for those summits,” said Torsten.

COLORADO

Exploring the ridge above Ranrapalca high camp with Nevado Tocllaraju in the background. PC: AAC Member Torsten Lyon.

The two made it safely back to Colorado narrowly missing the political unrest in Peru. Upon returning from Peru the two explored the American Alpine Club Library located in Golden, CO. They got lost in guidebooks written 30-50 years ago about the Cordillera Blanca— comparing conditions, climbs, and peaks to their experience.

The trip was a culmination of their climbing skills that they worked forward. They laid the foundation and built climbing and decision-making skills to minimize the risks in big mountain climbing. Now that they have a foundation of skills, they are prepared for new adventures in faraway places like the Canadian Rockies or the Alps, or in their backyard in the Colorado Rockies. You can find Camden studying maps and guidebooks for their next great adventure.