The Line is the monthly newsletter of the American Alpine Journal.

In this edition of “The Line,” American Alpine Journal editor-in-chief Dougald MacDonald offers his annual insider’s guide to the newest AAJ, pointing out a few gems that readers may overlook. “The AAJ mainly exists to document new climbs, but it’s a testament to our contributors’ creativity that their stories are rarely dry,” says MacDonald. “Nearly every report reveals something unexpected: a moment of humor or fear, or a bit of climbing history. You never know what you might find.”

This online feature is made possible by Hilleberg the Tentmaker, presenting sponsor of the AAJ’s Cutting Edge Podcast.

Deep in the Fango

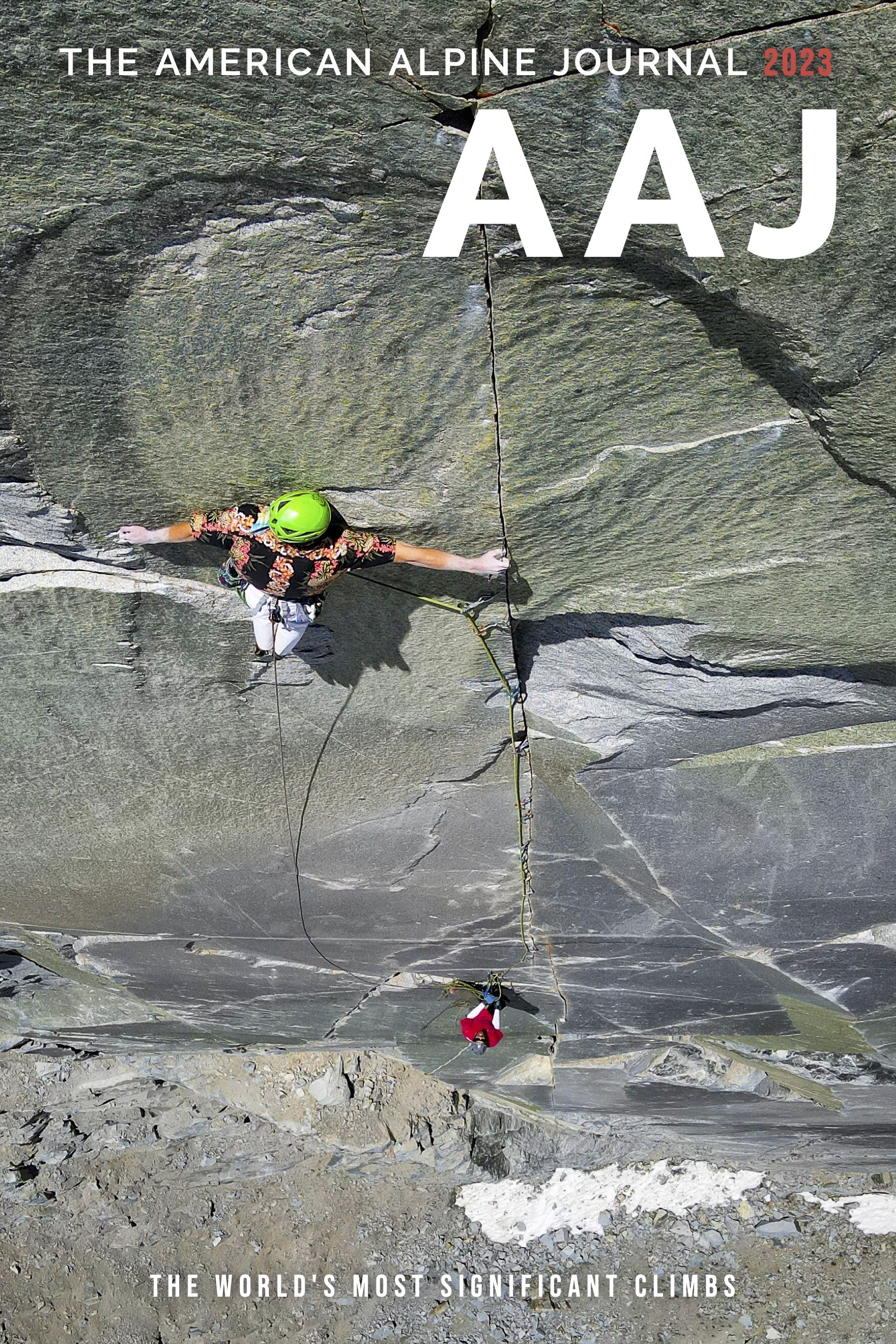

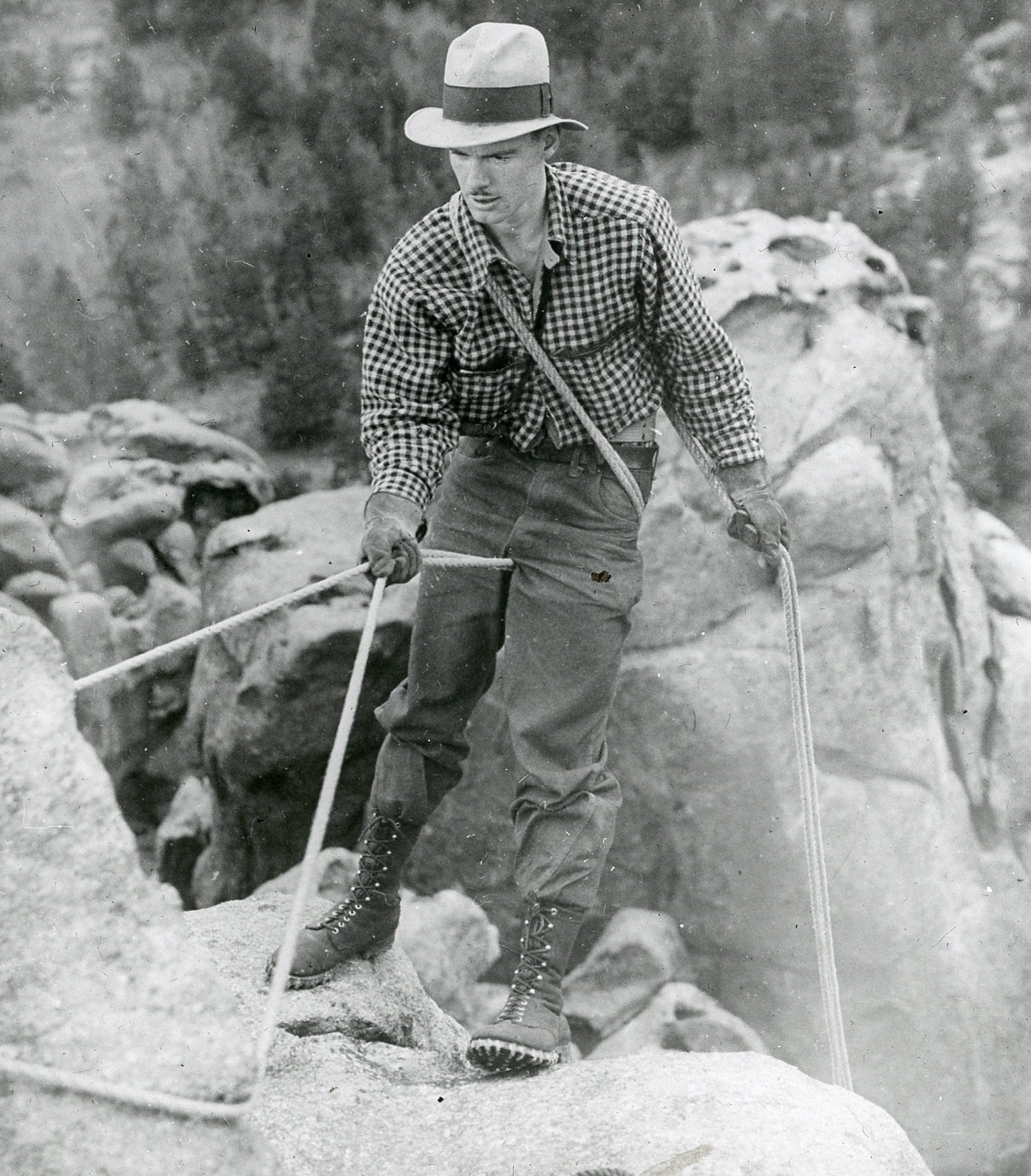

Aritza Monasterio trying not to get stuck in the fango on the east face of Hualcán in Peru. Photo by Andrej Jež.

I love a route name with interesting origins, and so it was hard to ignore the fact that two new routes in Peru’s Cordillera Blanca shared the word fango in their names: Fango Fiesta, the first route up the east face of Hualcán, climbed in early July last year, and Fango, Mushrooms, and Cornice, the first ascent of the southwest face of Caraz II, done in August. Both teams included Aritza Monasterio, a resident of Huaraz, whose original home was in Spain. It turns out the Spanish word fango means “mire” or “mud.” Anyone who has attempted to wallow up unconsolidated snow on the shady side of Peru’s big peaks will know exactly how these names originated.

By the way, the “cornice” part of the Caraz II route name has a pretty wild backstory—check it out on page 208 of the new book or read it online.

The Source

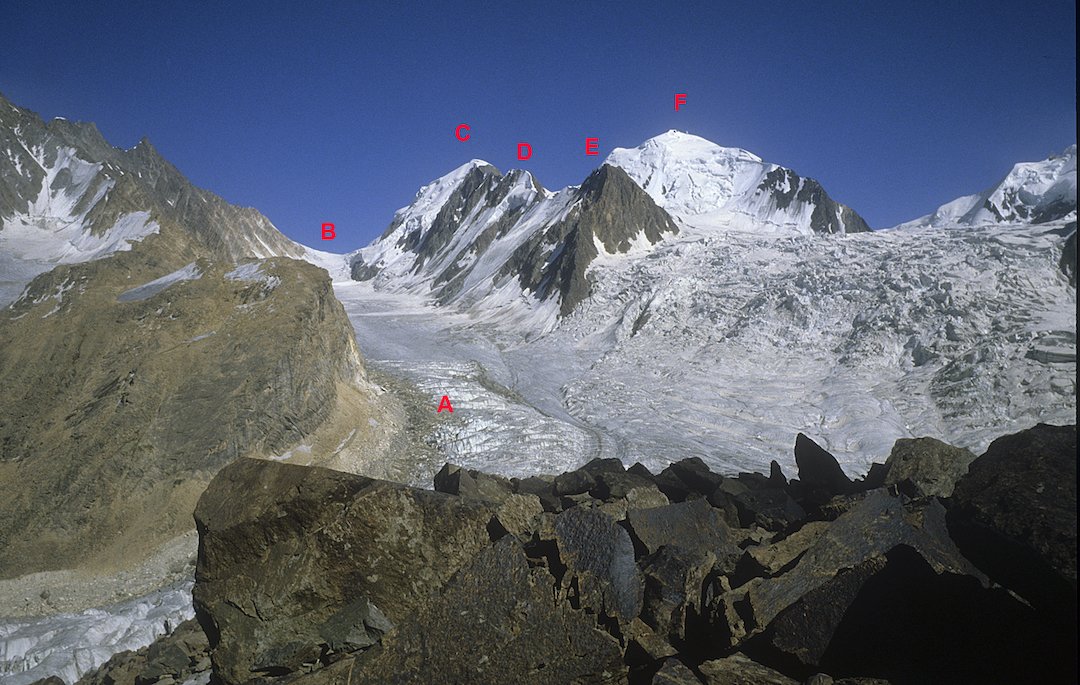

Lindsay Griffin, the AAJ’s senior editor, is without a doubt the premier chronicler of alpine and Himalayan climbing in the English language. He began working at the AAJ in 2003, and before that he had long contributed to the famed “Mountain Info” section of various British magazines—a sort of mini-AAJ that appeared in every issue—starting with the esteemed Mountain magazine around 1990. Based in North Wales, Lindsay has made dozens of first ascents all around the world, and his knowledge of obscure and remote mountains—and the ability to recall details of their ascents—is astonishing.

Yet somehow, various climbs of Lindsay’s have never made it into the pages of the AAJ. This year, prompted perhaps by the renaming of peaks he climbed and named decades ago, he shared an account of a two-person trip in 1984 to the Sumayar Valley, near Rakaposhi in Pakistan. Climbing solo or with partner Jan Solov, Lindsay made the first ascents of six technical peaks up to 5,750 meters. I’ve asked him to dig into his file cabinets for more stories!

Don Quixote for a Day

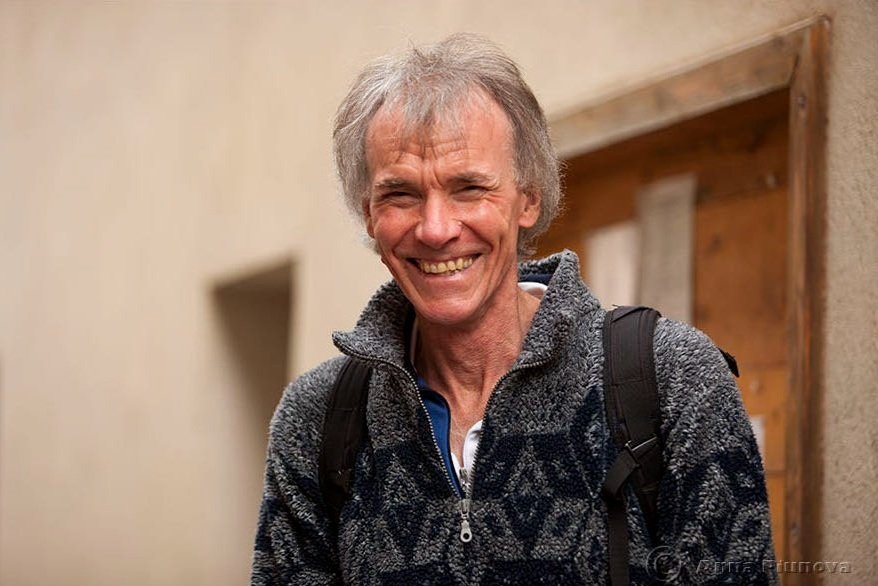

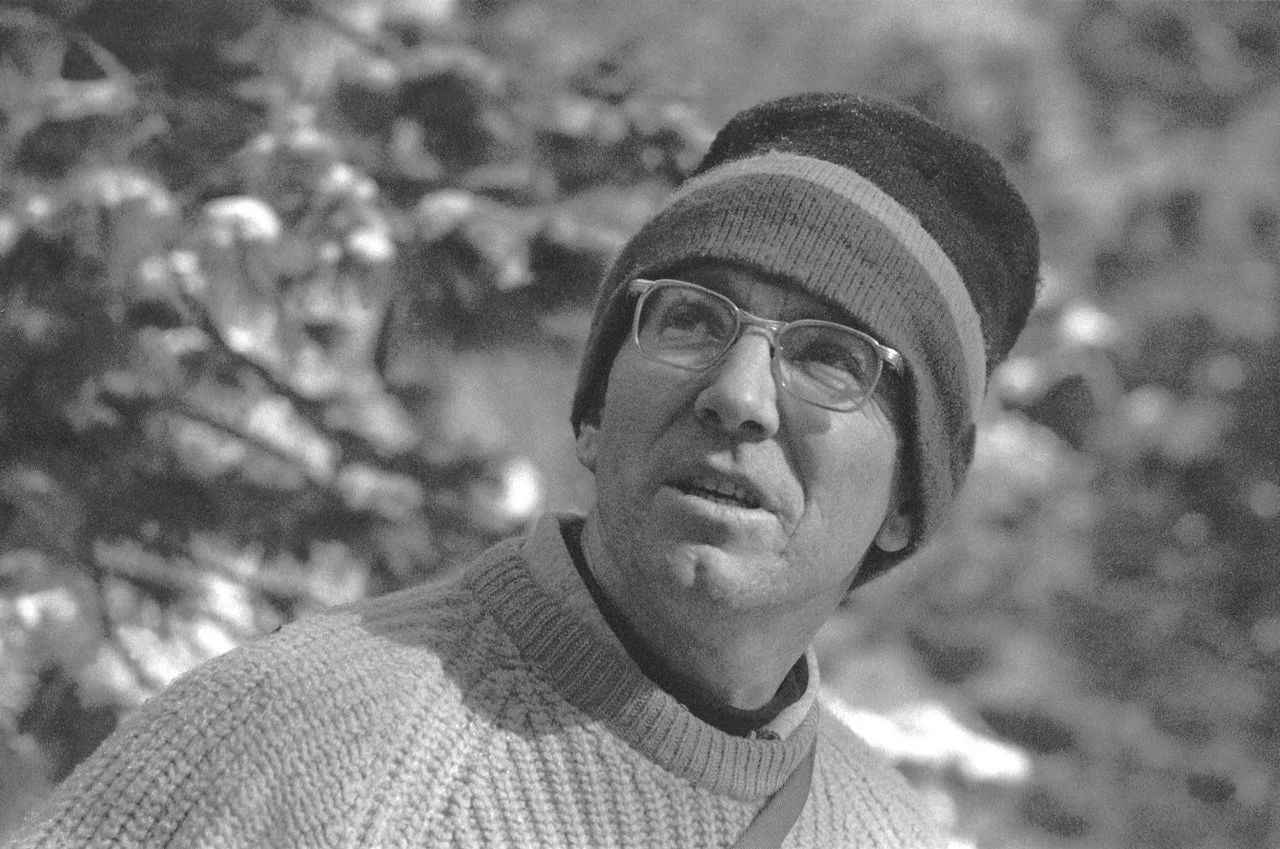

Photo © Jim Herrington.

Some of the best writing in the AAJ often can be found in the In Memoriam section, where climbing partners and friends recall the people they loved. Sometimes, not all of their tales will fit into the printed edition, but we always tell the full stories at the AAJ website. This was the case with John Thackray’s lovely tribute to mountaineer Roman Laba, who died last December; one anecdote in Thackray’s piece, summarized here, appears only at the website.

In the mid-1970s, traveling from Peru to Bolivia, Thackray and Laba caught a ride in an open truck packed with local people and uniformed soldiers, some of whom began harassing some young women in the truck. Despite a fierce altitude headache, Laba leapt to the women’s defense, confronting the soldiers and yelling at the ringleader in Spanish, “What kind of man are you? Why not pick on someone your own size? Me!” Fortunately, this confrontation ended with laughter instead of bloodshed. Years later, Laba recalled to Thackray, “I was Don Quixote for one day. And it was great.”

By the way, our photo of Laba is by Jim Herrington, creator of the brilliant 2017 book of portraits called The Climbers. Jim said he shot this photo of Laba in a tent during a ski tour in the Sierra Nevada in 1999, and that his friend was passing some time by reading a book by the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau…in French.

Advanced Rockcraft

Readers of the AAJ occasionally may glean information about new techniques making the rounds of advanced climbers. I remember, for example, when climbers started mentioning the use of ice hammocks to help pitch tents on steep ice and snow slopes. (The ice hammock was invented by Mark Richey and first described in AAJ 2012 during his account of the first ascent of Saser Kangri II, with Steve Swenson and Freddie Wilkinson, in 2011.) In this year’s book, I noted several new-ish techniques for moving efficiently in the mountains.

One of these is “fix and follow,” described by Vince Anderson in his story, starting on page 42 of the new AAJ, about a difficult climb on Jirishanca on Peru with Josh Wharton. With this technique, the leader fixes the rope at the end of a pitch, and then, instead of ascending the fixed rope, the follower self-belays with a Micro Traxion (backed up), so she or he can attempt to free the pitch while the leader relaxes, rehydrates, and prepares for the next pitch. As you’ll hear in the newest Cutting Edge podcast, covering the second ascent of the Cowboy Ridge on Trango Tower, parties of three also use this technique: The leader can start up the next pitch, belayed by the second, while the third climber is freeing the pitch below.

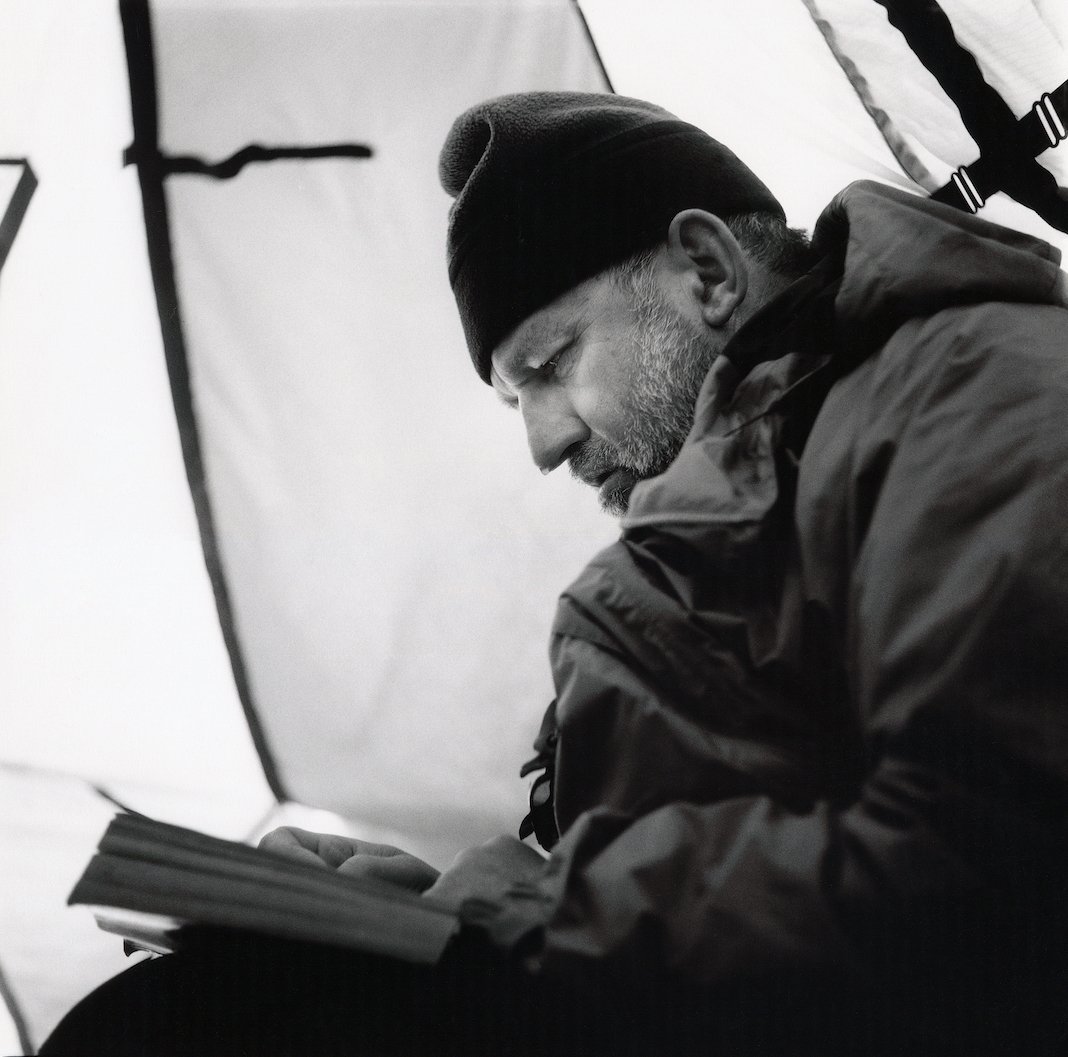

Krasnoyarsk style on the north face of Pik Korolyova. Photo courtesy of Nadya Oleneva.

In Nadya Oleneva’s story about a direct new route up the north face of Pik Korolyova in Kyrgyzstan last summer, she described another interesting technique: “When the wall became steeper, we switched to the ‘Krasnoyarsk style,’” Oleneva wrote in the AAJ. “The leader climbed for 30 meters, made an anchor, fixed a second rope at its midpoint, and then continued climbing; the belayer ascended the fixed rope and at the same time belayed the leader with a Grigri [on the lead rope], while the third member of the team ascended the rope below. This allows the team to climb very quickly, and we climbed all the difficult sections in this style.”

Been There, Done That

“The first time I saw the north face of Table Mountain, I got pulled over for driving too slowly.”

Sometimes a quote just resonates with me, like this one from a report about a recent route near Tucson, Arizona. I definitely can relate: Although I’ve never been pulled over by the cops for scoping while driving, my wife sometimes insists on taking the wheel when we drive up or down a rock-lined canyon, because I can’t keep my eyes on the road!

The Power of Youth

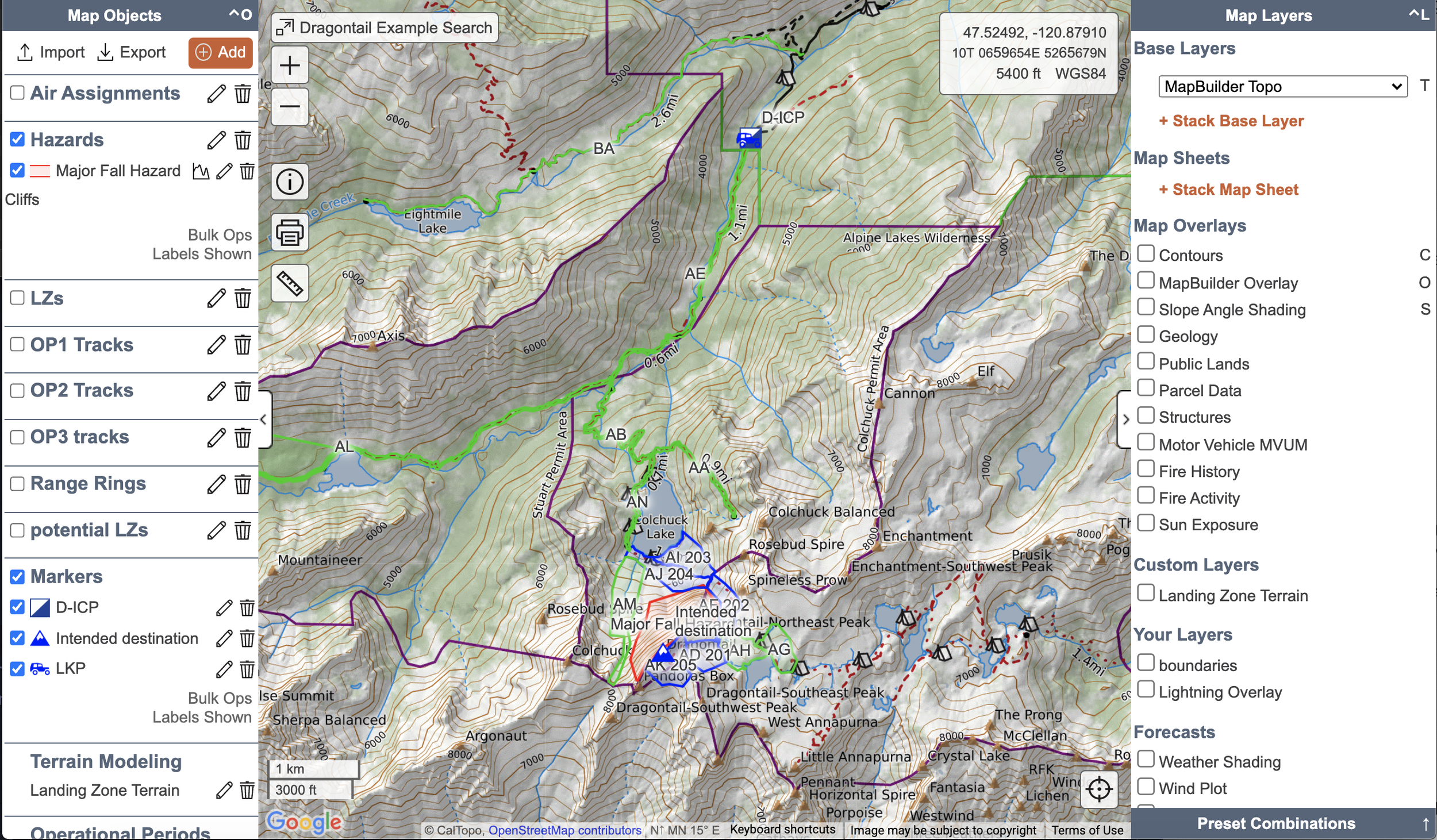

For climbers of a certain age, like me, it can be astonishing to see the strength and motivation of younger climbers—and to remember that, way back when, similar strength resided in our own legs and lungs. The new AAJ reports three long new routes and a significant repeat by Sam Boyce and partners in the remote and rugged Picket Range of the North Cascades—where brutal two-day approaches are the norm—all during the span of a single month last summer.

Sam Boyce on top of East Twin Needle in the Southern Pickets after the first ascent of the north buttress. The 4,000-vertical-foot Mongo Ridge of Mt. Fury’s west summit drops into the valley behind him on the left. Photo by Eric Wehrly.

Boyce, a 28-year-old guide, and Lani Chapko, another guide, first made the third ascent of the Mongo Ridge of Mt. Fury, including the second ascent of the Pole of Remoteness, named because it might be the hardest-to-reach point in the Lower 48. Boyce then paired up with Joe Manning, made another two-day approach into the Northern Pickets, and climbed the 2,000-foot south ridge of Spectre Peak. At the end of July, Boyce and Eric Wehrly climbed the north buttress of East Twin Needle in the Southern Pickets. Boyce and Chapko then returned to the Northern Pickets to climb the 2,000-foot south buttress of Whatcom Peak (likely the first route in that entire cirque). “We only had three days off work—a short window for the Pickets—but we were motivated,” Chapko wrote in the AAJ. She added, “We did the 16-mile approach, with 6,000 feet of gain, in one day.”

Fred Beckey described the Pickets this way: “Although the wild and jagged Picket Range is only 95 miles from the center of Seattle, it remains the most unexplored region in the Lower 48 because of its rugged nature.” Thanks to Boyce and his stalwart partners, it's a little less unexplored now.

South Yuyanq’ Ch’ex

The northwest face of South Yuyanq’Ch’ex in the Chugach Mountains, showing the line of We Fear Change (1,700’, WI4 M4). Photo by Elliot Gaddy.

The relabeling of certain mountains and routes that had troublesome names, though controversial to some climbers, continues to gain traction. In the Chugach Mountains of Alaska, the twin summits once known as Suicide Peaks, visible from Anchorage, were renamed North and South Yuyanq’ Ch’ex last October. At the end of that month, Dana Drummond and Elliot Gaddy climbed a cool new ice and mixed route up the northwest face, calling it We Fear Change (1,700’, WI4 M4). The peaks’ new name is from a Denai’ina Athabascan phrase meaning “breath from above” or “heaven’s breath.” That’s a very beautiful name for a mountain.

This edition of The Line and the AAJ’s Cutting Edge podcast both are presented by Hilleberg the Tentmaker, which has been making strong, versatile tents for more than 50 years. Visit Hilleberg’s website to order “The Tent Handbook,” their super-informative catalog.