Performance Characteristics.

ABD manufacturers will each try to convince consumers that their products represent the most secure, reliable, easy-to-use device on the market. The truth is that climbing has diverse contexts with diverse environments, climates, and risks. That diversity is further compounded by the number people who climb: big people, small people, big hands, small hands, right-handed people, and left-handed. Some people are missing digits or limbs, and that might make one product more advantageous than the next.

When combined with function and the need for multi-functionality, each device will also have an array of performance characteristics that depend on each individual user’s style, body type, and unique challenges. Asking the following questions of every ABD will guide a user to the right model.

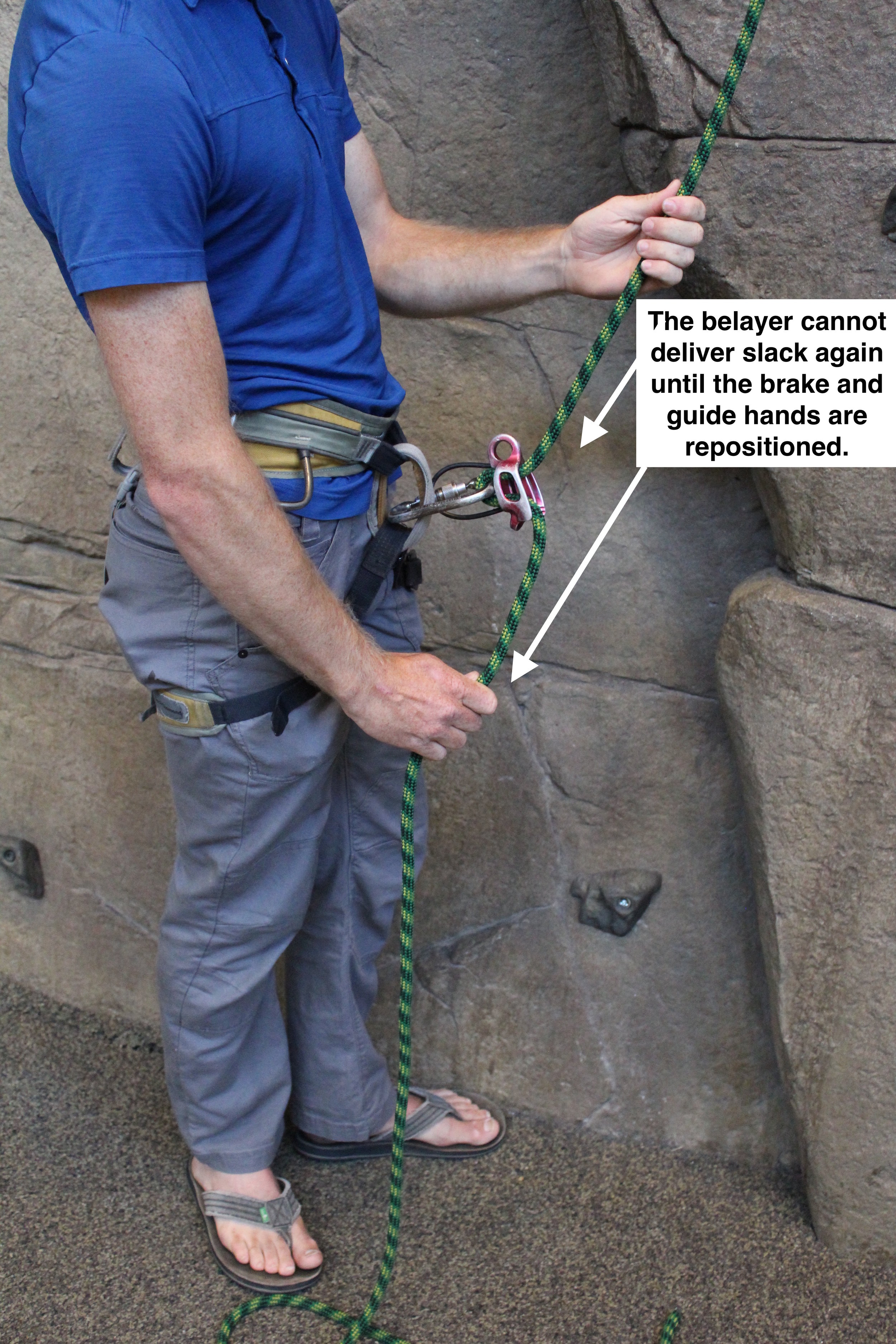

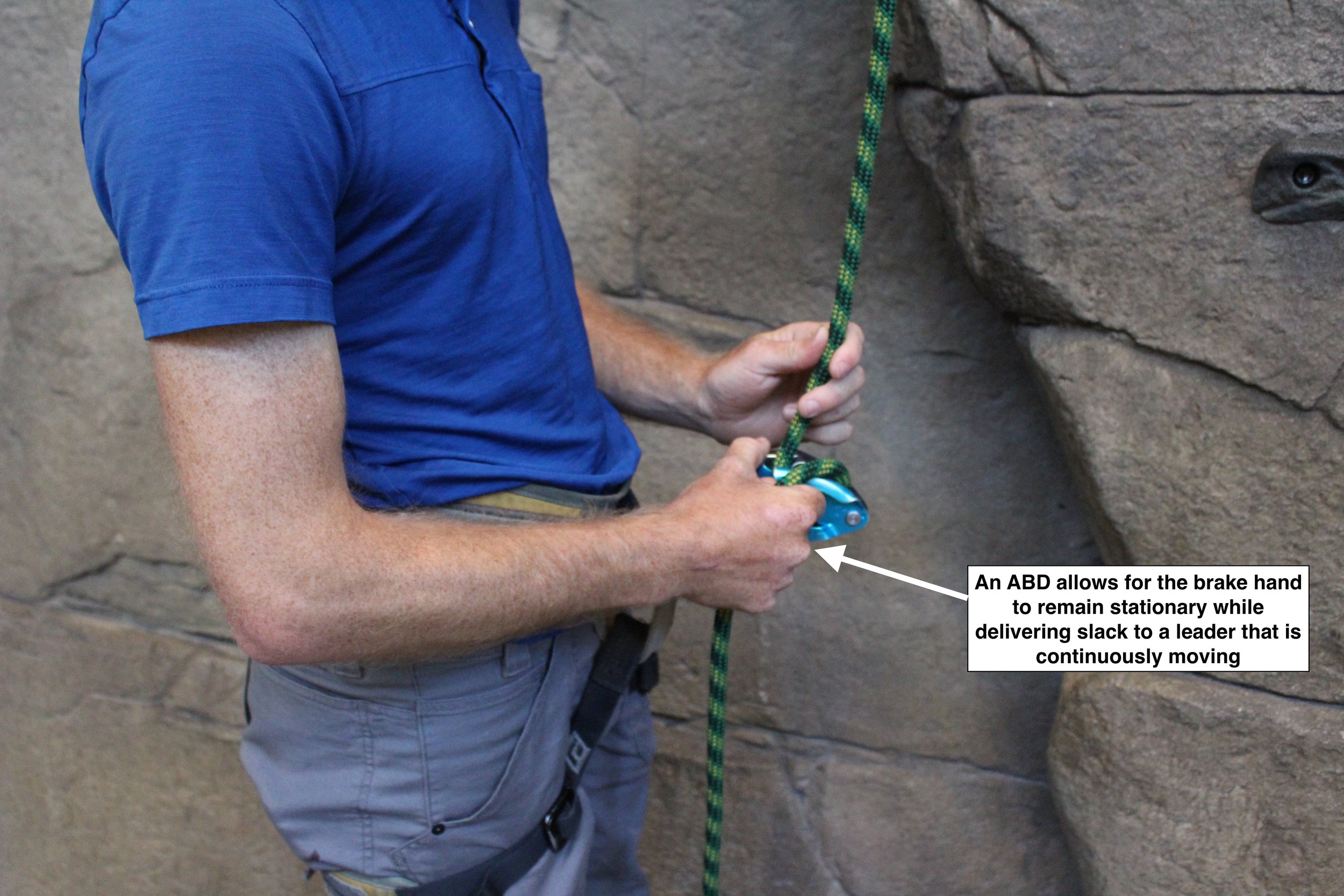

Stationary Brake Hand: Does the manufacturer recommend a belay technique that allows the brake hand to remain stationary? Many devices do allow for this movement economy, and it is one of the most persuasive reasons to select an ABD in the first place.

Mechanical Braking or Passive Braking: Is the assisted braking function mechanical or passive? Mechanical Assisted Braking Devices, like the GriGri 2 or Vergo, have moving cams, clamps or swivels that pin the brake strand of the rope. They are typically bigger and heavier than their passive counterparts. Their performance can be challenged in wet, snowy, or icy conditions. They can provide smooth lowers, multi-functionality, and reliable braking, though.

Passive Assisted Braking Devices exaggerate the “grabbing” quality of any aperture or tube style belay device. The “grabbing” effect is so severe, it effectively brakes the rope, providing the belayer with a backup.

Ergonomics: Does the recommended use of the tool force the belayer to sustain unnatural, painful, or uncomfortable body positions? Test the ergonomics of a device in all the application contexts. For example, the body mechanics involved in using a GriGri 2 are quite natural and comfortable for rappelling and counterweight belaying. But, lowering with a GriGri in a direct belay configuration requires an awkward manipulation of the GriGri 2 handle.

Reliability of Assisted Braking Function: Does the Assisted Braking Function perform reliably in the widest range of conditions and circumstances? What are the known malfunction conditions? No ABD is automatic and 100% reliable. They all have quirky and unique failure mechanisms that range from interference in the braking function’s range of motion, interference caused by precipitation (frozen or otherwise), inappropriate carabiner selection, or rope entrapment. Manufacturers don’t always advertise these failure mechanisms.

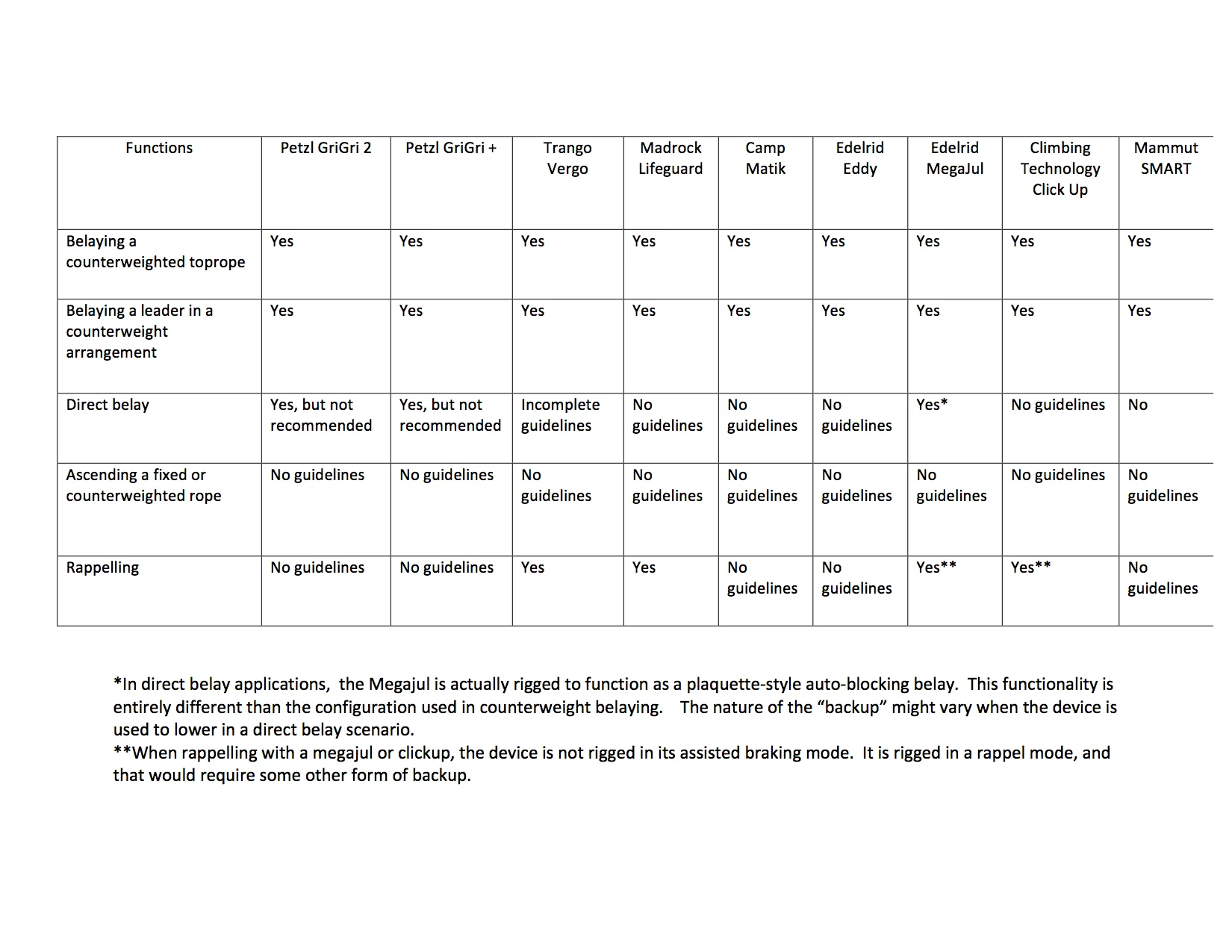

Multi-functionality: Does the device perform more than one function in climbing? Do all the functions of the tool fall under the device's recommended use? Are some functions discouraged, or are they simple NOT encouraged?

Smooth lowering and rappelling: When lowering and rappelling, is the belayer able to control the rate of descent and keep that rate constant, without sudden halts or acceleration? The ability to adjust the rate and the consistency of the rate varies from one tool to the next, and it can be especially inconsistent when using ropes at the extreme ends of the recommended range, ropes that are wet, or with smaller statured people.

Ambidextrous Usage: Is the device effectively unusable by a right or left-handed belayer? Does it function equally well with either handedness? Many devices do not offer a compelling left-handed technique. Left-handed belayers often learn to use their right hands to belay because there is not a recommended technique, or the recommended technique is not as effective as simply learning the right-handed technique.

Size and Weight: How big and how heavy is the tool? Are there lighter options that accomplish the same functions and have the same performance characteristics otherwise? In climbing, the size and weight of equipment can often make a big difference to the overall enjoyment and success of the team. All other things being equal, why not have a lighter, more compact tool?

Rope twisting: Does the device alter the plane of the rope’s travel? When ropes move continuously in the same plane of travel, the rope is less likely to twist. When that plane alters, say from a horizontal to vertical plane, twisting the rope is the unavoidable consequence.

Easy to learn, easy to teach: How long will it take me to learn to use the tool? Devices that are not ergonomic, have intricate parts and setups, and operate differently than other tools can often be more difficult for a belayer to learn to use correctly. It shouldn’t take months and months of practice to learn to use a piece of belay hardware.